полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, No. 401, March 1849

"I have noticed the crude and hostile speculations that are afloat, especially respecting financial reform, not only because I consider them to be very dangerous to the country; not only because, according to rumour, they have converted the Government; but because, avowedly on the part of their promulgators, they are only tending to ultimate efforts. This I must say of the new revolutionary movement, that its proceedings are characterised by frank audacity. They have already menaced the church, and they have scarcely spared the throne. They have denounced the constitutional estates of the realm as antiquated and cumbrous machinery, not adapted to the present day. No doubt, for the expedition of business, the Financial Reform Association presents greater facilities than the House of Commons. It is true that it may be long before there are any of those collisions of argument and intellect among them which we have here; they have no discussions and no doubts; but still I see no part of the go-a-head system which is likely to supersede the sagacity and matured wisdom of English institutions; and so long as the English legislature is the chosen temple of free discussion, I have no fear, whatever party may be in power, that the people of England will be in favour of the new societies. I know very well the difficulties which we have to encounter – the dangers which illumine the distance. The honourable gentleman, who is the chief originator of this movement, made a true observation when he frankly and freely said, that the best chance for the new revolution lay in the dislocation of parties in this House. I told you that, when I ventured to address some observations to the house almost in the last hour of the last session. I saw the difficulty which such a state of things would inevitably produce. But let us not despair; we have a duty to perform, and, notwithstanding all that has occurred, we have still the inspiration of a great cause. We stand here to uphold not only the throne, but the empire; to vindicate the industrial privileges of the working classes; to reconstruct the colonial system; to uphold the church, no longer assailed by appropriation clauses, but by vizored foes; and to maintain the majesty of parliament against the Jacobin manœuvres of Lancashire. This is a stake not lightly to be lost. At any rate, I would sooner my tongue were palsied before I counselled the people of England to lower their tone. Yes, I would sooner quit this House for ever than I would say to the people of England that they overrated their position. I leave that delicate intimation to the fervid patriotism of the gentlemen of the new school. For my part, I denounce their politics, and I defy their predictions; but I do so because I have faith in the people of England, their genius, and their destiny!"

Our views therefore are simply these – that while it is the duty of government to enforce and practise economy in every department of the public service, they are not entitled, upon any consideration whatever, to palter with the public safety. We cannot, until the estimates are brought forward, pronounce any judgment upon the merits of the proposed reductions – we cannot tell whether these are to be numerical, or effected on another principle. Needless expenditure we deprecate as strongly as the most sturdy adherent of the League, and we expect and hope that in several departments there will be a saving, not because that has been clamoured for, but because the works which occasioned the outlay have been completed. For example, the introduction of steam vessels into our navy has cost a large sum, which may not be required in future. But to assign, as ministers have done, the position of affairs abroad as a reason for reducing our armaments, is utterly preposterous. It is a miserable pretext to cover their contemptible truckling, and we are perfectly sure that it will be appreciated throughout the country at its proper value. It remains to be seen whether these estimates can be reduced so low as to meet the expenditure of the country. Our own opinion is, that they cannot, without impairing the efficiency of either branch of the service; and we hardly think that ministers will venture to go so far.

Let us, at all events, hope that Lord John Russell and his colleagues are not so lost to the sense of their duty, as to make the sweeping reduction which the Manchester politicians demand – that they will not consent to renounce the colonies, or to leave them destitute of defence. Still the question remains – how are we to raise our revenue? To this point we perpetually recur, for it is in this that the real difficulty lies. What says her Majesty's Government to this? The answer is quite short – Nothing. They have no scheme, so far as we are given to understand. They cannot go back upon indirect taxation; the country will not stand any increase of the direct burdens. The old rule was, out of two evils choose the least: the new rule seems to be, choose neither the one nor the other, but let matters go on as they best can. We have that confidence in the good sense of the country, that we cannot believe that this laissez faire system will be much longer tolerated. The family party, as the interwoven clique of Russells, Mintos, Greys, and Woods, has not unaptly been designated, was not placed in power merely to enjoy the sweets of office, or to provide for their numerous kindred; they must either grapple with the pressing difficulties of the state, or surrender their places to others who are more confident and capable.

Confidence is not wanting in certain quarters, though capability may be a matter of more dubiety. Mr M'Gregor, M.P. for Glasgow, and concocter of the famous free-trade tables, is ready at a moment's notice to produce a new financial scheme, founded upon unerring data, and promising a large increase of the revenue. Cobden has another scheme on the irons with the same view, benevolently proposing to lay the land of Great Britain under further contribution. We believe that, after the experience of the past, few people will be likely to accept either budget without considerable hesitation. Both gentlemen have committed a slight mistake in imitating Joseph's interpretation of the dream of Pharaoh; they should have inversed the order, and given the years of famine the precedence of the years of plenty.

The truth is, that it is a very simple matter to take off existing taxes, but marvellously difficult to impose new ones. Granting that a certain sum is required for the annual engagements and expenditure of the country, no wise statesman would abolish any source of revenue, without, at the same time, introducing another equivalent. Our error has been abolition without any equivalent at all. It is all very well to say, that by reducing import duties upon particular articles you stimulate the power of production: that stimulus may be given – individuals may in consequence be enriched – and yet still there is a defalcation of revenue. This, however, is the best case which can be pointed out for the reduction of duties, and can only apply, in any degree, to imports of raw material. The greater part of Sir Robert Peel's tariff is founded upon a principle directly opposite to this. He removed import duties from articles which, so far from stimulating the power of production at home, absolutely crushed that power, by bringing in foreign to supersede British labour. Thus, in both cases, there was a sacrifice. In the one there was, at all events, a direct sacrifice of revenue; in the other, a sacrifice of revenue, and a sacrifice of labour also. The imposition (and the word is appropriate either in its plain or its metaphorical meaning) of the property and income tax, which gave Sir Robert Peel the power of making his commercial experiments, proved inadequate to replace the deficit. The promised gain was as visionary as the dividends on certain railway lines projected about the same period, and no new source of national income has been opened to supply the loss.

Lord Brougham, no bad judge of human nature, observed the other night, that "such was the extent of the self-conceit of mankind, such the nature and amount of human frailty, that it became no easy matter to induce a nation to retrace its steps." People are ever loath to accept as facts the most pregnant evidences of their own deliberate folly. Perfectly aware of this metaphysical tendency, we are not surprised that, for the last two or three years, every remonstrance against the dangers of precipitate commercial legislation should have been treated with scorn, both by the older advocates of the abolition system, and by the younger disciples who were converted in a body along with their master. They have been kind enough, over and over again, to entreat us to relinquish our defence of what they called an antiquated and worn-out theory. Their supplications on this score have been so continuous as to become absolutely painful; nor could we well understand why and wherefore they should be so very solicitous for our silence. Our worst enemies cannot accuse us of advocating any dangerous innovations: our preachment may be tedious, but, at all events, we do not take the field at the head of an organised association. Neither can we be blamed for solitary restiveness, for we do not stand alone in the utterance of such opinions. The public press of this country has nobly fought the battle. We have had to cope with dexterous and skilled opponents; but never, upon any public question, has a great cause been maintained more unflinchingly, more disinterestedly, and more ably, than that of the true Conservative party by the free Conservative press. We are now glad to see that our denunciations of the new system have not been altogether without their effect. The temporary failure of free trade has been conceded even by its advocates; but we are referred to accidental causes for that failure, and the entreaty now is, to give the system a longer trial. We have no manner of objection to this, provided we are not asked to submit to any further experiments. We desire nothing better than that the people of Great Britain, be they agriculturists, or be they tradesmen, should have the opportunity of testing by experience the blessings of the free-trade system. The first class, indeed, do not require any probationary period of low prices to strengthen their conviction of the fallacy of the anti-reciprocity system, or of the iniquity of the arrangement which compels them to support the enormous amount of pauperism engendered by the over amount of population, systematically encouraged by the manufacturers. "The manufacturers," said Lord Brougham, "do not, perhaps, tell the world that they manufacture other things besides cotton twist; but every one who knew anything of them, knew that they manufactured paupers. Where the land produced one pauper, manufacturers created half-a-dozen." Still we can hardly expect to be thoroughly emancipated from the effects of the great delusion, until men of every sort and quality are practically convinced that their interests have been sacrificed to the selfish objects of a base and sordid confederation. We have no wish to hark back without occasion, or prematurely, to the corn laws: but, at the same time, we are not of the number of those who think that subsequent events have justified the wisdom of the measure. If the loyalty of the people of Great Britain did really rest upon so very narrow a point, that, even amidst the rocking and crashing of thrones and constitutions upon the Continent, ours would have been endangered by the maintenance of the former law, we should still have reason to despair of the ultimate destinies of the country. Are we to understand that, in such a case, the Jacobin faction would have had recourse to arms – that the Manchester League would have preached rebellion, or excited its adherents to insurrection? If not this, where would have been the danger? Never was any question agitated in which the mass of the operatives took less interest than in the repeal of the corn laws. They knew well that no benefit was thereby intended to be conferred upon them – that no philanthropic motives contributed to the erection of the bazaars – that the millions of popular tracts were poured forth from no cornucopia of popular plenty. The very fact, that the hard and griping men of calico were so liberal with their subscriptions to promote an agrarian change, was sufficient of itself to create a strong suspicion in their minds; for when was the purse of the taskmaster ever produced, save from a motive of selfish interest? We will not do the masses of the British population the foul injustice to believe that, under any circumstances, they would have emulated the frantic example of the French. Cobden has not yet the power of his friend and correspondent Cremieux: he is a wordy patriot, but nothing more; and, even had he been inclined for mischief, we do not believe that, beyond the immediate pale of his confederates, any considerable portion of the nation would readily have rallied round the standard of such a Gracchus, even though the tricolor stripes had been displayed on a field of the choicest calico.

"The corn law is a settled question!" so shout the free-traders daily, in high wrath and dudgeon if any one even ventures to allude to agricultural distress. We grant the fact. It is a settled question, like every other which has been decided by the legislature, and it must remain a settled question until the legislature chooses to reopen it. We do not expect any such consummation for a long time. We agree perfectly with the other party, that it is folly to continue skirmishing after the battle is over, and we do not propose to adopt any such tactics. We are content to wait until the experiment is developed, to see how the system works, and to accept it if it works well; but not on that account shall we less oppose the free-traders when they advance to further innovations. The repeal of the corn laws was not the whole, but a mere branch of the free-trade policy. It was undoubtedly the branch more calculated than any other to depress the agricultural interest, but the trial of it has been postponed longer than the free-traders expected. They shall have the benefit of that circumstance; nor shall we say one word out of season upon the subject. But perhaps, referring again to the Queen's speech, and selecting this time for our text those paragraphs which stated that "commerce is reviving," and that "the condition of the manufacturing districts is likewise more encouraging than it has been for a considerable period," we may be allowed to offer a few observations.

We do not exactly understand what her Majesty's ministers mean by the revival of commerce. This is a general statement which it is very easy to make, and proportionally difficult to deny. If they mean that our exports during the last half year have increased, we can understand them, and very glad indeed we are to learn that such is the case. For although we have seen of late some elaborate arguments, tending, if they have any meaning at all, to show that our imports and not our exports should be taken as the true measure of the national prosperity, we have that faith in the simple rules of arithmetic which forbids us from adopting such reasoning. But our gladness at receiving such a cheering sentiment from the highest possible authority is a good deal damped by the result of the investigations which we have thought it our duty to make. We have gone over the tables minutely, and we find that the exports of the great staples of our industry – cotton, woollen, silk, linen, hardware, and earthenware – were of less value than those of 1847 by FOUR MILLIONS AND A HALF, and less than those of 1846 by a sum exceeding FIVE MILLIONS AND A HALF. With such a fact before us, can it be wondered at if we are cautious of receiving such unqualified statements, and exceedingly doubtful of the good faith of the men who make them?

But, perhaps, this is not the sense in which ministers understand commerce. They are entitled to congratulate the country upon one sort of improvement, which certainly was not owing to any efforts upon their part. We have at last emerged from the monetary crisis, induced by the unhappy operation of the Banking Restriction Act, and, in this way, commerce certainly has improved. The fact that such a change in the distribution of the precious metals should have taken place whilst our exports were steadily declining, is very instructive, because it clearly demonstrates the false and artificial nature of our present monetary system. The consequences, however, may be serious, as the price of the British funds cannot now be taken as an index of the prosperity of the country, either in its agricultural or its manufacturing capacity, but has merely relation to the possession of a certain quantity of bullion. The rise of the funds, therefore, does not impress us with any confidence that there has been a healthy revival in the commerce of the country. We cannot consider the question of commerce apart from the condition of the manufacturing districts; and it is to that quarter we must look, in order to test the value of the free-trade experiments.

We have already noticed the enormous decrease, during the last three years, in the annual amount of our exports. This, coupled with the immense increase of imported articles of foreign manufacture, proves very clearly that the British manufacturer has as yet derived no benefit from the free-trade measures. We do not, of course, mean to say that free trade has had any tendency to lessen our exports, though to cripple the colonies is certainly not the way to augment their capabilities of consumption. We merely point to the fact of the continued decrease, even in the staples of British industry, as a proof of the utter fruitlessness of the attempt to take the markets of the world by storm. We are told, indeed, of exceptional causes which have interfered with the experiment; but these causes, even allowing them their fullest possible operation, are in no way commensurate with the results. For be it remarked, that the free-trade measures contemplated this result, – that increased imports were to be compensated by an enormous augmentation of exports: in other words, that we were to meet with perfect reciprocity from every foreign nation. Now, admitting that exceptional causes existed to check and restrain this augmentation, can we magnify these to such an extent as to explain the phenomenon of a steady and determined fall in our staple exports, and that long before the occurrence of civil war or insurrection on the continent of Europe? The explanation is just this, – the exports fell because the markets abroad were glutted, and because no state is disposed to imitate the suicidal example of Britain, or to sacrifice its own rising industry for the sake of encouraging foreigners. What inducement, it may be asked, has any state in the world to follow in our wake? Let us take for example Germany, to whose markets we send annually about six millions and a half of manufactures. Germany has considerable manufactures of her own, which give employment to a large portion of the population. Would it be wise in the Germans, for the sake of reducing the price either of linen, cotton, or woollen goods by an infinitesimal degree, to throw all these people idle, and to paralyse labour in every department, whenever they could be undersold by a foreign artisan? Undoubtedly not. Germany has nothing whatever to gain by pursuing such a course. The British market is open to her, but she does not on that account relax her right of laying duties upon imports from Britain. She shelters herself against our competition in her home market, augments her revenue thereby, and avails herself to the very utmost of our reduced tariffs, to compete in our country with the artisans of Sheffield and Birmingham. Every new return convinces us more and more that commercial interchange is the proper subject of international treaty; but that no nation whatever, and certainly not one so heavily burdened as ours, can hope for prosperity if it opens its ports without the distinct assurance of reciprocity.

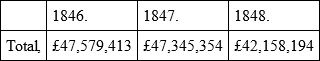

Let us try distinctly to ascertain the real amount of improvement visible in the manufacturing districts. In order to do this, we must turn to the last official tables, which bring down the trade accounts from 5th January to 5th December 1848, being a period of eleven months. We find the following ominous result in the comparison with the same period in former years: —

Exports of British Produce and Manufactures from the United Kingdom.

Five millions, two hundred thousand pounds of decreased exports in eleven months! – and the manufacturing districts are improving!

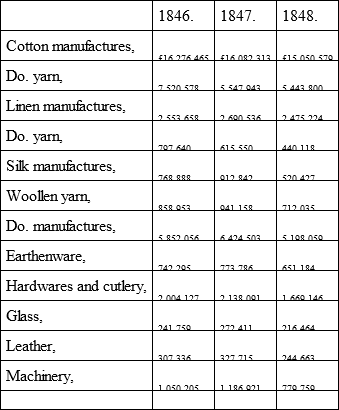

Let us see the ratio of decline on some of the principal articles which are the product of these districts. We shall therefore omit such entries as those of butter, candles, cheese, fish, soap, salt, &c., and look to the staples only. The following results we hardly think will bear out the somewhat over-confident declaration of the ministry: —

Export of Principal Manufactures from the United Kingdom.

Looking at these tables, we fairly confess that we can see no ground for exultation whatever; on the contrary, there is in every article a marked and steady decline. Some of the free-trade journals assert that, although in the earlier part of the last year there certainly was a marked falling off in our exports, yet that the later months have almost redeemed the deficiency. That statement is utterly false and unfounded. In September last, we showed that the exports of the first seven commodities in the above table, exhibited a decline of £3,177,370, for the six earlier months of the year, as compared with the exports in 1847. We continue the account of the same commodities for eleven months, and we find the deficiency rated at £3,370,603; so that we still have been going down hill, only not quite at so precipitate a rate as before. Free-trade, therefore – for which we sacrificed our revenue, submitted to an income-tax, and ruined our West India colonies – has utterly failed to stimulate our exports, the end which it deliberately proposed.

The diminution of exports implies of course a corresponding diminution of labour. This is a great evil, but one which is beyond the remedy of the statesman. You cannot force exports – you cannot compel the foreign nations to take your goods. We beg attention to the following extract from the speech of Mr D'Israeli, which puts the matter of export upon its true and substantial basis: —

"Look at your condition with reference to the Brazils. Every one recollects the glowing accounts of the late Vice-president of the Board of Trade with respect to the Brazilian trade – that trade for which you sacrificed your own colonies. There is an increase in the trade with the Brazils of 26,500,000 of yards in 1846 over 1845; and 18,500,000 yards in 1847 over 1845; and this increase has so completely glutted that market, that goods are selling at Rio and Bahia at cost price. It is stated in the Mercantile Journal, that 'It is truly alarming to think what may be the result of a continuance of imports, not only in the face of a very limited inquiry, but at a period of the year when trade is almost always at a stand. Why cargo after cargo of goods should be sent hither, is an enigma we cannot solve. Some few vessels have yet to arrive; and although trade may probably revive in the beginning of 1849, what will become of the goods received and to be received? This market cannot consume them. Stores, warehouses, and the customhouse are full to repletion; and if imports continue upon the same scale as heretofore, and sales have to be forced, we may yet have to witness the phenomenon of all descriptions of piece goods being purchased here below the prime cost in the country of production!' Such is the state of matters in these markets; and I do not see that your position in Europe is better. Russia is still hermetically sealed, and Prussia is not yet stricken. I know that there are some who, at this moment, think that it is a matter of no consequence how much we may export; who say that foreigners will not give their productions for nothing, and that, therefore, we must just manage things in the most favourable way we can for ourselves. There is no doubt that foreigners will not give us their goods without some exchange for them; but the question which the people of this country are looking at is, to know exactly what are the terms of exchange which it is beneficial for us to adopt. That is the whole question. You may glut markets, as I have shown you have succeeded in doing; but the only effect of your system, of your attempting to struggle against those hostile tariffs, by opening your ports, is that you exchange more of your labour every year and every month for a less quantity of foreign labour; that you render British labour or native industry less efficient; that you degrade British labour – necessarily diminish profits, and, therefore, must lower wages; while the first philosophers have shown that you will finally effect a change in the distribution of the precious metals that must be pernicious to this country. It is for these reasons that all practical men are impressed with the conviction that you should adopt reciprocity as a principle of your commercial tariff – not merely from its practical importance, but as an abstract truth. This was the principle of the negotiations at Utrecht, which was copied by Mr Pitt in his commercial negotiations at Paris, which formed the groundwork of the instructions to Mr Eden, and which was wisely adopted and upheld by the cabinet of Lord Liverpool; but which was deserted, flagrantly, and openly, and unwisely, in 1846. There is another reason why you can no longer defend your commercial system – you can no longer delay considering the state of your colonies. This is called an age of principles, and no longer of political expedients – you yourselves are the disciples of economy; and you have, on every occasion, enunciated it as a principle that the colonies of England were an integral part of this country. You ought, then, to act towards your colonies on the principle you have adopted, but which you have never practised. The principle of reciprocity is, in fact, the only principle on which you can reconstruct your commercial system in a manner beneficial to the mother country and advantageous to the colonies. It is, indeed, a great principle, the only principle on which a large and expansive system of commerce can be founded, so as to be beneficial. The system you are pursuing is one quite contrary – you go fighting hostile tariffs with fixed imports; and the consequence is that you are following a course most injurious to the commerce of the country. And every year, at the commencement of the session, you come, not to congratulate the House or the country on the state of our commerce, but to explain why it suffered, why it was prostrate; and you are happy on this occasion to be able to say that it is recovering – from what? From unparalleled distress."