полная версия

полная версияAbridgement of the Debates of Congress, from 1789 to 1856 (4 of 16 vol.)

The gentleman from Connecticut (Mr. Goodrich) informs us, that the public councils are pressing on to measures pregnant with the most alarming results. I hope the gentleman is mistaken in his apprehensions, and I should have been much pleased if the gentleman had been good enough to point them to a better course; but, sir, he has not done so, nor has any gentleman on the same side of the question. Indeed, sir, it would give me great pleasure to do something that would be agreeable to our Eastern friends; but, unfortunately, amidst all the intrinsic difficulties which press upon us, that seems to be not among the least of them. The gentlemen themselves will not explicitly tell us what would produce the effect – and I am inclined to think that nothing short of putting the Government in their hands would do it. Even this would not be exempt from difficulties. The gentlemen from that part of the United States are nearly equally divided among themselves respecting the proper course of measures to be pursued, and there is an immense majority in every other part of the United States, in favor of the measures proposed; we are therefore surrounded with real and intrinsic difficulties from every quarter, and those of a domestic nature are infinitely the most formidable, and most to be deprecated. Indeed, sir, under present circumstances, the administration of the Government cannot be a pleasant task; and, in my judgment, it requires a great effort of patriotism to undertake it, not on account of external pressures, but on account of internal discontents, stimulated, too, by so many artful intrigues. But for these unfortunate circumstances, every gentleman would feel an honorable pride in contributing his efforts to devise measures for repelling foreign aggressions, and he would court the responsibility attached to his station. I would not, Mr. President, give up a scintilla of that portion of the responsibility which the crisis imposes on me. Indeed, sir, to have the honor of bearing my full share of it, is the only inducement I have at this moment for occupying a place on this floor. Without that consideration I should now be in retirement. But when I turn my eyes upon internal divisions, discontents and violations of law, and am compelled to think of measures for their suppression, it produces the most painful sensations and distressing reflections.

The great principle of objection, the gentlemen tell us, consists in the transfer of legislative powers to the Executive Department. This is an old an abstract question, often heretofore brought into view, and leads to endless discussion. I think I shall be able to show that the bill introduces no new principle in this respect, but only applies an established principle to new practical objects. The general principle of the separation of departments is generally admitted in the abstract; but the difficulties in this discussion arise from applying the principle to practical objects. The great difficulty exists in the attempt to fix on the precise boundary line between legislative and Executive powers in their practical operation. This is not possi-1 You might attempt the search for the philosopher's stone, or the discovery of the perpetual motion, with as much prospect of success. The reason of this difficulty is, that the practical objects and events to which this abstract principle is attempted to be applied, are perpetually varying, according to the practical progression of human affairs, and therefore cannot admit of any uniform standard of application. This reflection might have saved the gentleman from Massachusetts (Mr. Lloyd) the trouble of reading to us the constitution or bill of rights of Massachusetts, in which the principle of separation of departments is very clearly and properly laid down, and which will be very readily assented to in the abstract, but which forms no part of the question in dispute. It cannot, however, escape observation, that this principle is not laid down, even in the abstract, in the Constitution of the United States; and, although it is the leading principle of the constitution, and probably was the principal guide in its formation, it is nevertheless in several respects departed from.

This body partakes essentially both of the legislative and Executive powers of the Government. The Executive Department also partakes of the legislative powers, as far at least as an approbation of, and a qualified negative of the laws extend, &c. I make these observations, however, not in derogation of the general principle of the separation of powers among the several departments, so far as is practicable, but merely to show that there must necessarily be some limitations in its practical operation. Perhaps the best general rule for guiding our discretion upon this subject will be found to consist in this: That legislation ought to extend as far as definition is practicable – when definition stops, execution must necessarily begin. But some of the particular provisions of this bill will furnish more precise illustrations of my opinions upon this question; it will, therefore, be waived until I shall come to their consideration.

I will now proceed to examine the more particular objections urged against the detail of this bill. Its provisions respecting the coasting trade are said to be objectionable in the following respects:

First objection: The penalty of the bonds required, is said to be excessive. To enable us to decide correctly upon this point, the object proposed to be effected, and the penalty required, should be considered in reference to each other. The object is to prevent, by means of coasting vessels, domestic articles from being carried abroad. Flour, for instance, to the West Indies. The price of that article here is less than five dollars; in the West Indies it is said to be thirty and upward. The penalty of the bonds required is six times the amount of the value of the vessel and cargo. Is any gentleman prepared to say a smaller penalty will effect the object? I presume not. Indeed, the committee were disposed to put it at the lowest possible point, consistently with an effectuation of the object; and probably it is rather too low for that purpose. As to the penalty, according to the tonnage of vessels, it is believed no alteration in the existing laws is made in that respect. These penalties will appear the more reasonable, when it is recollected, that through the indulgence given of the coasting trade, most of the violations of the embargo laws have been contrived and effected.

Second objection: The collectors may be influenced by party spirit in the exercise of their discretion. It is hoped that this will not be the case, and if it were, it would certainly be much to be regretted. It may, however, probably happen, and is one of the inconveniences of the system.

Third objection: The high penalties of the bonds will drive many persons of small means from their accustomed occupations. They will not be able to procure the competent security for their prosecution. It is not to be presumed that this will be the effect to any great extent. If the owner is known to be honest, and has in view legal and honest objects, I have very little apprehension of his not being able to get the security required. But here the question recurs, are these apprehended inconveniences of such a nature as to render it necessary to abandon a great national object, for the accommodation of a few individuals who are affected by them? Is the last effort to preserve the peace of the nation, to be abandoned from these considerations? I should conclude, certainly not.

The next objections are made to the seventh section of the bill, which provides that stress of weather, and other unavoidable accidents at sea, shall not be given in evidence in a trial at law to save the penalty of bonds given as security against the violation of the embargo laws. It is known that, through pretexts derived from this permission, at present, most of the violations of these laws have been committed with impunity – it is, therefore, important to the future execution of the laws, to take away these pretexts. But it is objected that this regulation manifests a distrust of oaths. It does, of what is called custom-house oaths; their violation is already almost proverbial; it does not, however, produce nor encourage this profligacy; it takes away the temptation to it. It is further said, it impairs the trial by jury – very far from it; the trial by jury still exists; this provision only regulates the evidence to be produced before the jury. Gentlemen state particular hardships which may take place under this regulation. It is easy to state possible hardships under any general regulation; but they have never been deemed sufficient objections to general regulations producing in other respects beneficial results. This bill, however, contains a provision for relief in all cases of hardships under the embargo laws. The Secretary of the Treasury is authorized to grant relief in all such cases. This power, vested in the Secretary, is also objected to. It is said to manifest a distrust of courts, and to transfer their powers to the Secretary of the Treasury. Whatever may be my distrust of some of the courts of the United States, I can say that consideration furnished no inducement to this provision. It is a power not suited to the organization of courts, and it has for a long time been exercised by the Secretary of the Treasury without being complained of. Congress proceeded with great caution on this subject. On the third day of March, 1797, they first introduced this principle into their laws in relation to the collection of the revenue; and, after an experiment of nearly three years, on the eleventh day of February, 1800, they made the law perpetual. This will appear from the 12th section of this bill, which merely borrows this provision from pre-existing laws. It introduces no new principle whatever. This doctrine is carried still further, by an act passed the 3d of March, 1807, in the eighth volume of the laws, page 318:

"An Act to prevent settlements being made on lands ceded to the United States, until authorized by law.

"And it shall moreover be lawful for the President of the United States to direct the Marshal, or officer acting as Marshal, in the manner hereinafter directed, and also to take such other measures, and to employ such military force as he may judge necessary and proper, to remove from lands ceded, or secured to the United States by treaty, or cession as aforesaid, any person or persons who shall hereafter take possession of the same, or make or attempt to make a settlement thereon, until authorized by law."

Here the President is authorized to use the military force to remove settlers from the public lands without the intervention of courts; and the reason is, that the peculiarity of the case is not suited to the jurisdiction of courts, nor would their powers be competent to the object, nor, indeed, are courts allowed to interfere with any claims of individuals against the United States, but Congress undertakes to decide upon all such cases finally and peremptorily, without the intervention of courts.

This part of the bill is, therefore, supported both by principle and precedent.

While speaking of the distrust of courts, I hope I may be indulged in remarking, that individually my respect for judicial proceedings is materially impaired. I find, sir, that latterly, in some instances, the callous insensibility to extrinsic objects, which, in times past, was thought the most honorable trait in the character of an upright judge, is now, by some courts, entirely disrespected. It seems, by some judges, to be no longer thought an ornament to the judicial character, but is now substituted by the most capricious sensibilities.

Wednesday, December 21

Enforcement of the EmbargoMr. Pope spoke in favor of the bill.

And on the question, Shall this bill pass? it was determined in the affirmative – yeas 20, nays 7, as follows:

Yeas. – Messrs. Anderson, Condit, Crawford, Franklin, Gaillard, Giles, Gregg, Kitchel, Milledge, Mitchill, Moore, Pope, Robinson, Smith of Maryland, Smith of New York, Smith of Tennessee, Sumter, Thruston, Tiffin, and Turner.

Nays. – Messrs. Gilman, Goodrich, Hillhouse, Lloyd, Mathewson, Pickering, and White.

Wednesday, December 28

The Vice President being absent by reason of the ill state of his health, the Senate proceeded to the election of a President pro tempore, as the constitution provides; and Stephen R. Bradley was appointed.

Friday, January 6, 1809

Return Jonathan Meigs, jun., appointed a Senator by the General Assembly of the State of Ohio, to fill the vacancy occasioned by the resignation of John Smith, and, also, for six years ensuing the third day of March next, attended, and produced his credentials, which were read; and the oath prescribed by law was administered to him.

Tuesday, January 10

James A. Bayard, from the State of Delaware, attended.

Monday, January 16

The credentials of Michael Leib, appointed a Senator by the Legislature of the State of Pennsylvania, to fill the vacancy occasioned by the resignation of Samuel Maclay, were read, and ordered to lie on file.

Thursday, January 19

Michael Leib, appointed a Senator by the Legislature of the State of Pennsylvania, to fill the vacancy occasioned by the resignation of the Honorable Samuel Maclay, attended, and the oath prescribed by law was administered to him.

Tuesday, January 24

Foreign Intercourse – the Two Millions Secret Appropriation – Florida the objectThe following Message was received from the President of the United States:

To the Senate of the United States:

According to the resolution of the Senate, of the 17th instant, I now transmit them the information therein requested, respecting the execution of the act of Congress of February 21, 1806, appropriating two millions of dollars for defraying any extraordinary expenses attending the intercourse between the United States and foreign nations.

January 24, 1809.

TH. JEFFERSON.The Message and documents were read, and one thousand copies thereof ordered to be printed for the use of the two Houses of Congress.

In compliance with the resolution of the Senate, so far as the same is not complied with by the report of the Secretary of the Treasury of the 20th instant, the Secretary of State respectfully reports, that neither the whole nor any portion of the two millions of dollars appropriated by the act of Congress of the 21st of February, 1806, "for defraying any extraordinary expenses attending the intercourse between the United States and foreign nations," was ever authorized or intended to be applied to the use of either France, Holland, or any country other than Spain; nor otherwise to be applied to Spain than by treaty with the Government thereof, and exclusively in consideration of a cession and delivery to the United States of the territory held by Spain, eastward of the river Mississippi.

All which is respectfully submitted.

JAMES MADISON.Department of State, Jan. 21.

Monday, January 30

The Vice President having retired, the Senate proceeded to the election of a President pro tempore, as the constitution provides; and the Hon. John Milledge was appointed.

Thursday, February 2

The credentials of Samuel White, appointed a Senator by the Legislature of the State of Delaware, for six years, commencing on the 4th of March next, were read, and ordered to lie on file.

Tuesday, February 7

Examination and Count of Electoral Votes for President and Vice PresidentMr. Smith, of Maryland, from the joint committee appointed to ascertain and report a mode of examining the votes for President and Vice President, and of notifying the persons elected of their election, and for regulating the time, place, and manner, of administering the oath of office to the President, reported in part the following resolution, which was read and agreed to:

Resolved, That the two Houses shall assemble in the Chamber of the House of Representatives, on Wednesday next, at 12 o'clock; that one person be appointed a teller on the part of the Senate, to make a list of the votes as they shall be declared; that the result shall be delivered to the President of the Senate, who shall announce the state of the vote, and the persons elected, to the two Houses assembled as aforesaid; which shall be deemed a declaration of the persons elected President and Vice President, and, together with a list of the votes, to be entered on the Journals of the two Houses.

Ordered, That Mr. Smith, of Maryland, be appointed teller on the part of the Senate, agreeably to the foregoing resolution.

A message from the House of Representatives brought to the Senate "the several memorials from sundry citizens of the State of Massachusetts, remonstrating against the mode in which the appointment of Electors for President and Vice President has been proceeded to on the part of the Senate and House of Representatives of said State, as irregular and unconstitutional, and praying for the interference of the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States, for the purpose of preventing the establishment of so dangerous a precedent."

The message last mentioned, referring to the memorials of sundry citizens of the State of Massachusetts, was read.

Ordered, That the message and memorials lie on the table.

A message from the House of Representatives informed the Senate that the House agree to the report of the joint committee "appointed to ascertain and report a mode of examining the votes for President and Vice President, and of notifying the persons elected of their election, and to regulate the time, place, and manner of administering the oath of office to the President," and have appointed Messrs. Nicholas and Van Dyke tellers on their part.

Wednesday, February 8

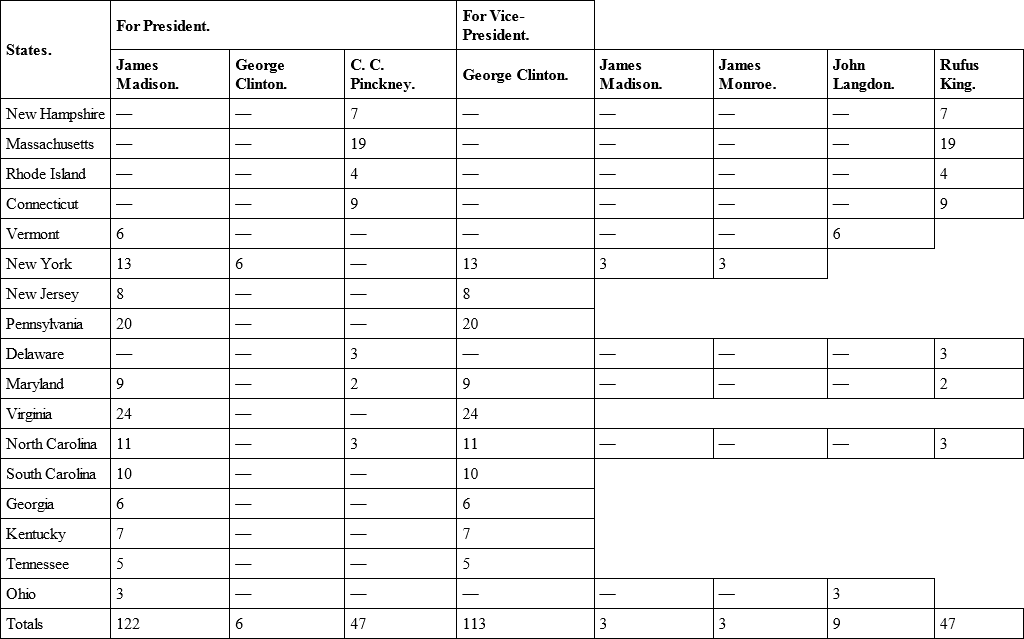

The two Houses of Congress, agreeably to the joint resolution, assembled in the Representatives' Chamber, and the certificates of the Electors for the several States were, by the President of the Senate, opened and delivered to the tellers appointed for the purpose, who, having examined and ascertained the number of votes, presented a list thereof to the President of the Senate, which was read, as follows:

The whole number of votes being 175, of which 88 make a majority.

Whereupon the President of the Senate declared James Madison elected President of the United States for four years, commencing with the fourth day of March next; and George Clinton Vice President of the United States for four years, commencing with the fourth day of March next.

The votes of the Electors were then delivered to the Secretary of the Senate; the two Houses of Congress separated; and the Senate returned to their own Chamber.

On motion, by Mr. Smith of Maryland,

Resolved, That the President of the United States be requested to cause to be delivered to James Madison, Esq., of Virginia, now Secretary of State of the United States, a notification of his election to the office of President of the United States; and to be transmitted to George Clinton, Esq., of New York, Vice President elect of the United States, notification of his election to that office; and that the President of the Senate do make out and sign a certificate in the words following, viz:

Be it known, That the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, being convened at the city of Washington, on the second Wednesday in February, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and nine, the underwritten, President of the Senate pro tempore, did, in presence of the said Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates and count all the votes of the Electors for a President and Vice President of the United States. Whereupon, it appeared that James Madison, of Virginia, had a majority of the votes of the Electors as President, and George Clinton, of New York, had a majority of the votes of the Electors as Vice President. By all which it appears that James Madison, of Virginia, has been duly elected President, and George Clinton, of New York, has been duly elected Vice President of the United States, agreeably to the constitution.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand, and caused the seal of the Senate to be affixed, this – day of February, 1809.

And that the President of the Senate do cause the certificate aforesaid to be laid before the President of the United States with this resolution.

Tuesday, February 21

The credentials of Joseph Anderson, appointed a Senator for the State of Tennessee, by the Executive of that State, from and after the expiration of the time limited in his present appointment, until the end of the next session of the Legislature thereof, were presented and read, and ordered to lie on file.

Franking Privilege to Mr. JeffersonThe bill freeing from postage all letters and packets to Thomas Jefferson was read the second time, and considered as in Committee of the Whole; and no amendment having been proposed, on the question, Shall this bill be engrossed and read a third time? it was determined in the affirmative.

Non-IntercourseMr. Tiffin, from the committee, reported the bill to interdict the commercial intercourse between the United States and Great Britain and France, and their dependencies, and for other purposes, correctly engrossed; and the bill was read the third time, and the blanks filled – section three, with the words twentieth and May in two instances.

On motion by Mr. Bradley, the words, "or being pursued by the enemy," were stricken out of the first and third sections, by unanimous consent.

Mr. Lloyd addressed the Senate as follows:

Mr. President: When the resolution on which this bill is founded was brought forward, I had expected it would have been advocated – as a means of preserving peace – as a menace to the belligerents, that a more rigorous course of conduct was about to be adopted towards them, on the part of the United States, provided they continued to persist in their injurious decrees, and Orders in Council – as giving us time to prepare for war – or as a covert, but actual war, against France and Great Britain.

I feel indebted to the honorable gentleman from Virginia, (Mr. Giles,) for not only having very much narrowed the consideration of this subject, but for the open, candid, and manly ground he has taken, both in support of the resolution and the bill. I understood him to avow, that the effect must be war, and that a war with Great Britain; that, notwithstanding the non-intercourse attached to this bill, the merchants would send their vessels to sea; those vessels would be captured by British cruisers; these captures would be resisted; such resistance would produce war, and that was what he both wished and expected. I agree perfectly with the gentleman, that this is the natural progress, and must be the ultimate effect of the measure; and I am also glad, that neither the honorable Senate nor the people of the United States can entertain any doubts upon the subject.

I understood the gentleman also to say, that this was a result he had long expected. Now, sir, as there have been no recent decrees, or Orders in Council issued, if war has been long looked for, from those now in operation, I know not what excuse those who have the management of our concerns can offer to the people of the United States, for leaving the country in its present exposed, naked, and defenceless situation.

What are our preparations for war? After being together four-fifths of the session, we have extorted a reluctant consent to fit out four frigates. We have also on the stocks, in the navy yard and elsewhere scattered along the coast, from the Mississippi to the Schoodick, one hundred and seventy gunboats, which, during the summer season, and under the influence of gentle western breezes, may, when in commission, make out to navigate some of our bays and rivers, not, however, for any effectual purposes of defence, for I most conscientiously believe, that three stout frigates would destroy the whole of them; and of the enormous expense at which this burlesque naval establishment is kept up, we have had a specimen the present session, by a bill exhibited to the Senate, of eight hundred dollars for medical attendance, on a single gunboat for a single month, at New Orleans. If other expenditures are to be made in this ratio, it requires but few powers of calculation to foretell that, if the gunboats can destroy nothing else, they would soon destroy the public Treasury.