полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 69, No. 425, March, 1851

Without going into details, unhappily too well known to all to require any lengthened illustration, it may be sufficient to refer to three circumstances which have not only immensely aggravated the internal distress and external disaffection of the empire, but interrupted and neutralised the influence of all those causes of relief provided for us by nature, and which, under a just and equal policy, would have entirely averted them.

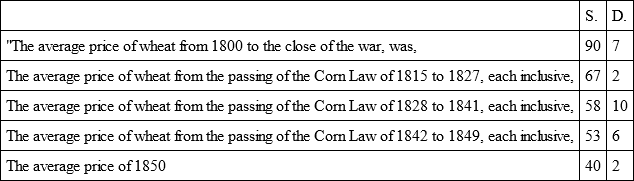

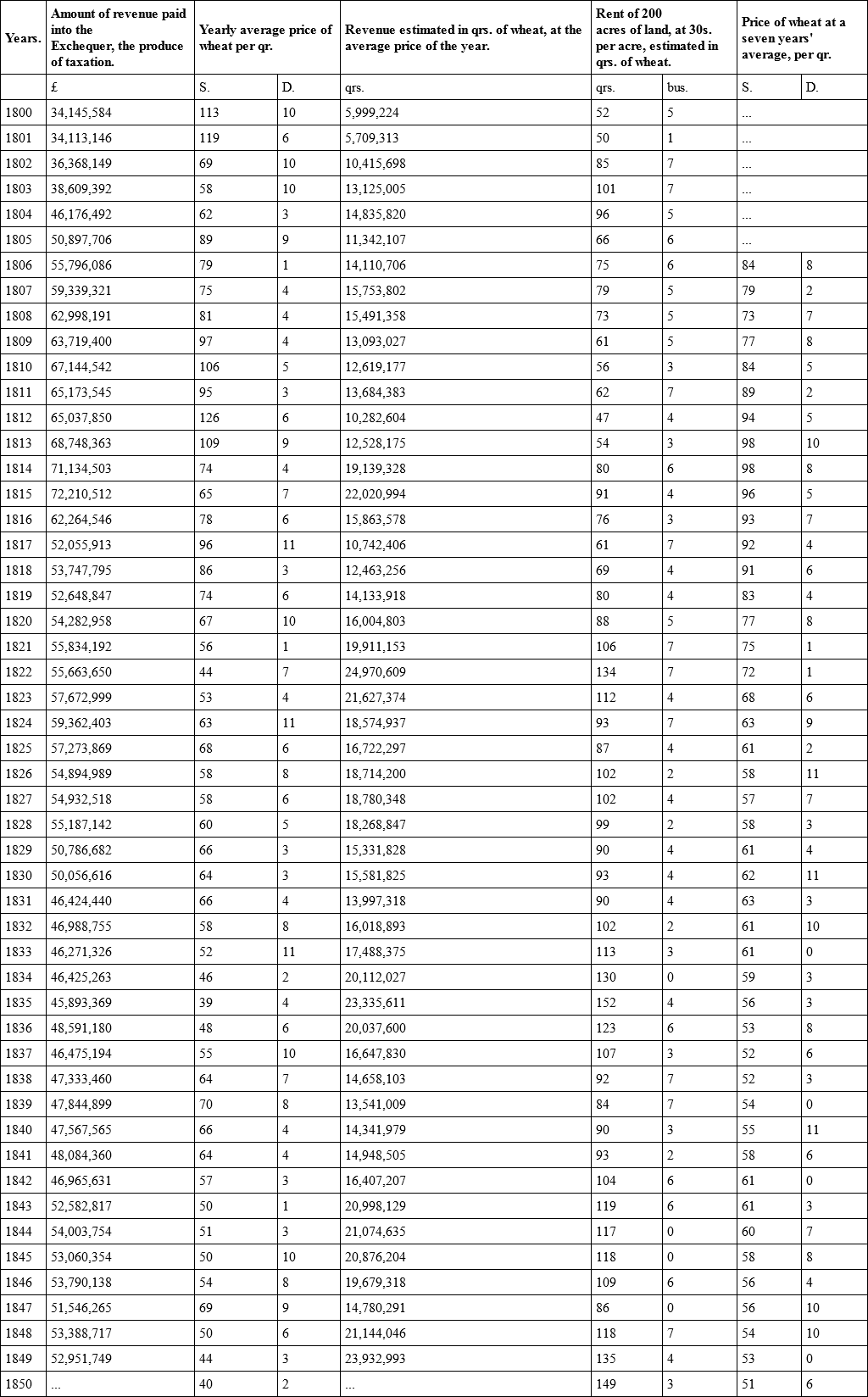

The first of these, and perhaps the most disastrous in its effects upon the internal prosperity of the empire, was the great contraction of the currency which took place by the bill of 1819. By that bill the bank and bankers' notes, which at the close of the war had amounted, in Great Britain and Ireland, to about £60,000,000 in round numbers, were suddenly reduced to £32,000,000, which was the limit formally imposed, by the acts of 1844 and 1845, on the circulation issuable on securities in the country. We know the effect of these changes: the Times has told us what it has been. It rendered the sovereign worth two sovereigns; the fortune of £500,000 worth £1,000,000; the debt of £800,000,000 worth £1,600,000,000; the taxes of £50,000,000 worth £100,000,000 annually. As a necessary consequence, it reduced the average price of wheat from 90s. to 40s.; and the entire wages of labour and remuneration of industry, throughout the country, to one-half of their former amount. The prodigious effect of this change upon the real amount of the national burdens, and the remuneration of the industry which was to sustain it, may be judged of by the invaluable table quoted on the next page, which is stated to be taken from Mr Porter's valuable work on the Progress of the Nation, published in 1847, and furnished by that gentleman with his wonted courtesy to the Midland Counties Herald, to the end of 1850. Its import will be found to be correctly condensed in the following statement, by that able writer Gemini, contained in the same paper of January 30: —

During the war the average quantity of wheat required to be sold to pay one million of taxation amounted to 220,791 quarters. The quantity required to be sold to pay one million of taxation, according to the prices of 1850, amounts to 497,925 quarters, or 56,343 quarters more than double the quantity required to be sold during the war. The enormous increase in the burdensomeness of taxation may be thus clearly estimated."

Comment is unnecessary, illustration superfluous, on such a result.

– Midland Counties Herald, January 31, 1851. The prices of wheat here given are the average prices of the year.

In the next place, prodigious as was the addition which this great change made to the burdens, public and private, of the nation, the change was attended with an alteration at times still more hurtful, and, in the end, not less pernicious. This was the compelling the bank to pay all their notes in gold, the restraining them from issuing paper beyond £14,000,000 bond on securities, and compelling them to take all gold brought to them, whatever its market value was, at the fixed price of £3, 17s. 10½d. the ounce. This at once aggravated speculation to a most fearful degree in periods of prosperity, for it left the bank no way of indemnifying itself for the purchase and retention of £15,000,000 or £16,000,000 worth of treasure but by pushing its business in all directions, and lowering its discounts so as to accomplish that object; and it led to a rapid and ruinous contraction of the currency the moment that exchanges became adverse, and a drain set in upon the bank, either from the necessities of foreign war in the neighbouring states, the mutation of commerce, or the occurrence of a large importation of grain to supply the wants of our own country. Incalculable as the distress which those alternations of impulse and depression have brought upon this great manufacturing community, and immeasurable the multitudes whom they have sunk, never more to rise, into the lowest and most destitute classes of society, their effect has by no means been confined to the periods during which they actually lasted. Their baneful influence has extended to subsequent times, and produced a continuous and almost unbroken stream of distress; for, long ere the victims of one monetary crisis have sunk into the grave, or been driven into exile, another storm arises which precipitates fresh multitudes, especially in the manufacturing towns, into the abyss of ruin. The whole, or nearly the whole, of this terrific and continued suffering is to be ascribed to the monstrous principles adopted in our monetary system – that of compelling the banks to foster and encourage speculation in periods of prosperity, and suddenly contract their issues and starve the body politic, when a demand for the precious metals carries them in considerable quantities out of the country. A memorable instance of the working of that system is to be found in the Railway mania of 1845 and 1846, flowing directly from the Acts of 1844 and 1845, which landed the nation in an extra expenditure of nearly £300,000,000 on domestic undertakings, at a time when commerce of every kind was in a state of the highest activity, followed by the dreadful crash of October 1847, which, by suddenly contracting the currency and ruining credit, threw millions out of employment, and strained the real capital of the nation to the very uttermost, to complete a part only of the undertakings which the Currency Laws had given birth to. And the example of the years 1809 and 1810 – when the whole metallic currency was drained out of the country by the demands for the war in the Peninsula and Germany, but no distress was experienced, and the national strength was put forth with unparalleled vigour, and, as it proved, decisive effect – proves how easily such a crisis might be averted by the extended issue of a paper currency not liable to be withdrawn, when most required, by a public run for gold.

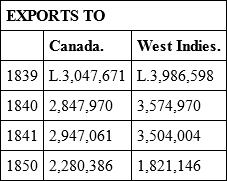

In the third place, to crown the whole, and as if to put the keystone in the arch of public distress, Free-Trade in every department was forced upon the country by Sir Robert Peel and his successors in 1846, 1847, and 1849, under the dictation of the Manchester school, and to promote the interest of master-manufacturers by lowering the wages of labour and of realised capital, by cheapening the price of everything else, and raising the value of money. We see the effects of this already evinced in every department to which the system has applied; and we see the commencement only of the general ruin with which it is fraught. In agriculture, Great Britain and Ireland, which were, practically speaking, in ordinary seasons self-supporting, have come already to import from nine to ten millions of foreign grain for the support of the inhabitants, besides sheep and cattle in an equal proportion. At least fifteen millions yearly is sent out of the country, for the most part in hard cash, to buy food, which formerly was nearly all spent in it, and enriched all classes of its people. The exchangeable value of what remains has been lowered by at least £75,000,000 annually, and of course so much taken away from the means of supporting domestic labour, and paying the national defences and the interest of public and private debt. The West Indies, formerly the right arm of the naval strength of England, and no small source of its riches, have been totally ruined; and, as a necessary consequence, the exports of our manufactures to those once splendid settlements, which, prior to the commencement of the new measures in 1834, had reached £3,500,000 a-year, had sunk in 1850 to £1,821,146! Canada has been so much impoverished by the withdrawing of all protection to colonial industry, which has annihilated its intercolonial trade with the West Indies, and seriously injured its export trade in grain and wood to this country, that the British exports to that country, which in 1839 amounted to £3,047,000, had sunk in 1850, notwithstanding the subsequent addition of above 50 per cent to its population, to £2,280,386.

In Ireland from four to five hundred thousand acres have gone out of the cultivation of wheat alone; although the calamitous failure of the potato crop in 1846, and the subsequent doubts as to the success of that prolific esculent, should have tended to an increase of cereal crops as the only thing that could be relied on, and undoubtedly would have done so, but for the blasting influence of Free Trade, which deprived the farmer of all hope of a profitable return for agricultural expenditure. As a necessary consequence, above 200,000 cultivators have disappeared from the soil of the Emerald Isle in the four last years; about 250,000 of them or their families are immured, idle and miserable, in the Irish workhouses, and above 40,000 in its prisons; while above 200,000 persons from that island alone, and 300,000 from the two islands, are annually driven into exile! Lastly, as if Free Trade had not worked sufficient mischief on the land, it has invaded the sea also; no longer can the Englishman say —

"His march is on the mountain waveHis home is on the deep."The ocean is fast becoming the home for other people, to the exclusion of its ancient lords. One single year of Free Trade in shipping, following the repeal of the Navigation Laws, has occasioned, under the most favourable circumstances for testing the tendency of the change, so great a diminution in British and increase in foreign shipping in all our harbours, that it is evident the time is rapidly approaching, if the present system is continued, when we must renounce all thought of maintaining naval superiority, and trust to the tender mercies of our enemies and rivals for a respite from the evils of blockade and famine.16

The vast emigration of 300,000 annually which is now going on from the United Kingdom, might reasonably be expected to have alleviated, in a great degree, this most calamitous decrease in the staple branches of industry in our people; and so it would have, certainly, had a wise and paternal Government taken it under its own direction, and sent the parties abroad who really were likely to want employment, and whose removal would at once prove a relief to the country from which they were sent, and a blessing to that for which they were destined. But this is so far from being the case, that there is perhaps no one circumstance in our social condition which has done more of late years to aggravate the want of employment, and enhance the distress among the working-classes, than the very magnitude of this emigration. The dogma of Free Trade has involved even the humble cabins of the emigrant's ship: there, as elsewhere, it has spread nothing but misery and desolation. The reason is, that it has been left to the unaided, undirected efforts of the emigrants themselves.

Government was too glad of an excuse not to interfere: the constantly destitute condition of the Treasury, and the ceaseless clamour against taxation, in consequence of the wasting away of the national resources under the action of Free Trade and a contracted currency, made them too happy of any excuse for avoiding any payments from the public Treasury, even on behalf of the most suffering and destitute of the community. This excuse was found in the plausible plea, that any advances on their part would interfere with the free exercise of individual enterprise – a plea somewhat similar to what it would be if all laws for the protection of paupers, minors, and lunatics, were swept away, lest the free action of the creditors on their estates should be disturbed. The consequence has been that the whole, or nearly the whole, of the immense stream of emigration which general distress has now caused to flow from the British Islands, has been sustained by the efforts of private individuals, and left to the tender mercies of the owners or freighters of emigrant ships. The result is well known. Frightful disasters, from imperfect manning and equipment, have occurred to several of these misery-laden vessels. A helpless multitude is thrown ashore at New York and Montreal, destitute alike of food, clothing, or the means of getting on to the frontier, where its labour could be of value; and the competition for employment at home has been increased to a frightful degree by the removal of so large a proportion of such of the tenantry or middle class as were possessed of little capitals; and had the means either of maintaining themselves or giving employment to others. At least L.3,000,000 yearly goes abroad with the emigrant ships, and that is drawn almost entirely from the lower class of farmers, the very men who employ the poor. The class who have gone away was for the most part that which should have remained, for it had the means of doing, something in the world, and employing others; that which was left at home, was that which should have been removed, because they were the destitute who could neither find employment in these islands, nor do anything on their own account from want of funds. Hence above a million and a-half of persons in Great Britain, and above seven hundred thousand in Ireland, on an average of years, are constantly maintained by the poor-rates, for the most part in utter idleness, although the half of them are able-bodied, and their labour – if they could only be forwarded to the frontier of civilisation in America – would be of incalculable service to our own colonies or the United States.

The very magnitude of the trade employed in the exportation of the emigrants, and the importation of food for those who remain, has gone far to conceal the ruinous effects of Free Trade. Between the carrying out of emigrants, and the bringing in of grain – the exportation of our strength, and the importation of our weakness – our chief seaports may continue for some time to drive a gainful traffic. The Liverpool Times observes: —

"The number of emigrant vessels which sailed from Liverpool during the last year, was 568. Of these vessels, many are from 1500 to 2000 tons burden, and a few of them even reach 3000 tons. They are amongst the finest vessels that ever were built, are well commanded, well-manned, fitted out in excellent style, and present a wonderful improvement in all respects, when compared with the same class of vessels even half a dozen years ago. Taking the average passage-money of each passenger in these vessels at £6, the conveying of emigrants yields a revenue of upwards of £1,000,000 sterling to the shipping which belongs to or frequents this port, independent of the great amount of money which the passage of such an immense multitude of persons through the town must cause to be spent in it. In fact, the passage and conveyance of emigrants has become one of the greatest trades of Liverpool." —Liverpool Times, Jan. 10, 1851.

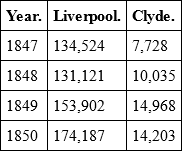

The number of emigrants from the Mersey and the Clyde, since the days of Free Trade began, have been prodigious, and rapidly increasing. They have stood thus: —

It was precisely the same in the declining days of the Roman empire – the great seaport towns continued to flourish when all other interests in the state were rapidly sinking; and when the plains in the interior were desolate, or tenanted only by the ox or the buffalo, the great cities were still the abodes of vast realised wealth and unbounded private luxury. We are rapidly following in the same path. The realised capital of Great Britain was estimated in 1814 at L.1,200,000,000; in 1841, Mr Porter estimated it at L.2,000,000,000; the capital subject to legacy duty in Great Britain, on an average of forty-one years, from 1797 to 1841, was L.26,000,000; in the single year 1840 it was L.40,500,000. The increase of realised capital among the rich has been nearly as great as that of pauperism, misery, and consequent emigration among the poor – the well-known and oft-observed premonitory symptoms of the decline of nations.

It is in the midst of these numerous and overwhelming evils, the result mainly of theoretical innovation and class government in the country – when above two millions of paupers in the two islands are painfully supported by public assessment; when three hundred thousand are annually driven into exile, and a hundred and fifty thousand more are constantly supported in jails, one-half of whom are committed for serious crimes;17 when all classes, excepting those engaged in the export trade of human beings and the import of human food, are languishing from the decline of domestic employment, and the constantly increasing influx of foreign goods, both rude and manufactured – that we are assured by one benevolent set of philanthropists that all will be right, if we only give the starving working-classes model houses, rented at L.8 each, to live in; by another, that ragged schools for their destitute children will set all in order; by a third, that a schoolmaster in every wynd is alone required to remove all the evils under which we labour; by a fourth, that cold baths and wash-houses to lave their emaciated limbs, are the great thing; by a fifth, that church extension is the only effectual remedy, and that, till there is a minister for every seven hundred inhabitants, it is in vain to hope for any social amelioration. We respect the motives which actuate each and all of these benevolent labourers in the great vineyard of human suffering; we acknowledge that each within a limited sphere does some good, and extricates a certain number of individuals or families out of the abyss of degradation or suffering in which they are immersed. As to anything like national relief, or alleviation of distress in any sensible degree, from their united efforts, when the great causes of evil which have been mentioned continue in undiminished activity, it is as chimerical as to expect by the schoolmaster or the washing-woman to arrest the ravages of the plague or the cholera.

Two circumstances of general operation, and overwhelming importance, render all these various and partial remedies, while the great causes which depress the demand for labour and deprive the people of employment continue in operation, entirely nugatory and ineffectual, in a general view, to arrest our social evils.

The first of these is, that these remedies, one and all of them, are calculated for the elevation and intellectual or moral improvement of the people, but have no tendency to improve their circumstances, or diminish the load of pauperism, destitution, and misery with which they are overwhelmed. Until the latter is done, however, all the efforts made for the attainment of the former, how benevolent and praiseworthy soever, will have no general effect, and, in a national point of view, may be regarded as almost equal to nothing. The reason is that, generally speaking, the human race are governed, in the first instance, almost entirely by their physical sufferings or comforts, and that intellectual or moral improvement cannot be either thought of or attended to till a certain degree of ease as to the imperious demands of physical nature has been attained. In every age, doubtless, there are some persons of both sexes who will heroically struggle against the utmost physical privation, and pursue the path of virtue, or sedulously improve their minds, under circumstances the most adverse, and with facilities the most inconsiderable. But these are the exceptions, not the rule. The number of such persons is so inconsiderable, compared to the immense mass who are governed by their physical sensations, that remedies addressed to the intellect of man, without reference to the improvement of his circumstances, can never operate generally upon society. Even the most intellectual and powerful minds must give way under a certain amount of physical want or necessity. Take Newton and Milton, Bacon and Descartes, Cervantes and Cicero, and make them walk thirty miles in a wintry day, and come in to a wretched hovel at night, and see what they will desire. Rely upon it, it will be neither philosophy nor poetry, but warmth and food. A good fire and a good supper would attract them from all the works which have rendered their names immortal. Can we expect the great body of mankind to be less under the influence of the imperious demands of our common physical nature than the most gifted of the human race? What do the people constantly ask for? It is neither cold baths nor warm baths, ragged schools nor normal schools, churches nor chapels, model houses nor mechanics' institutes – "It is a fair day's wage for a fair day's work." We would all do the same in their circumstances. Give them that, the one thing needful alike for social happiness and moral improvement, and you make a mighty step in social amelioration and elevation; because you lay the foundation on which it all rests, and on which it must, in a general point of view, all depend – without it, all the rest will be found to be as much thrown away as the seed cast on the arid desert.

In the next place, the intellectual cultivation and elevation which is regarded by so large a political party, and so numerous a body of benevolent individuals, as the panacea for all our social evils, never has affected, and never can affect, more than a limited class in society. We may indeed teach all, or nearly all, to read; but can we make them all read books, or still more, read books that will do them any good, when they leave school, and become their own masters, and are involved in the cares, oppressed with the labours, and exposed to the temptations of the world? Did any man ever find a fifth of his acquaintance of any rank, from the House of Peers and the Bar downwards, who were really and practically directed in manhood and womanhood by intellectual pleasures or pursuits? Habit, early training, easy circumstances, absence of temptation, a fortunate marriage, or the like, are the real circumstances which retain the great body of the human race of every rank in the right path. They are neither positively bad, nor positively good: they are characters of imperfect goodness, and mainly swayed by their physical circumstances. If you come to a crisis with them, when the selfish or generous feelings must be acted upon, nine-tenths of them will be swayed by the former. The disciples of Rousseau will contest these propositions: we would only recommend them to look around them, and see whether or not they are demonstrated by every day's experience in every rank of life. We wish it were otherwise; but we must take mankind as they are, and legislate for them on their average capacity, without supposing that they are generally to be influenced by the intellectual appliances adapted only to a small fraction of their number. And, accordingly, upon looking at the statistical tables given in the commencement of this Essay, it will be found that, while emigration, crime, and pauperism, have advanced rapidly, despite all the efforts of philanthropy and religion, which are permanent, but affect only a part of society, they exhibit the most remarkable fluctuations, according to the prosperity or distress of particular years, because the causes then in operation affected the whole of mankind.

The only way, therefore, in which the physical circumstances of the great body of mankind can be ameliorated, or room can be afforded for the moral and intellectual elevation of such of them as have received from nature minds susceptible of such training, is by restoring the equilibrium between the demand for labour and the numbers of the people, which our late measures have done so much to subvert. By that means, and that means alone, can the innumerable social evils under which we labour be alleviated. Without it, all the other remedies devised by philanthropy, pursued with zeal, cherished by hope, will prove ineffectual. How that is to be done must be evident to every person of common understanding. The demand for labour must be increased, the supply of labour must be diminished. The first can only be done, by a moderate degree of Protection to Native Industry, at present beat down to the dust in every department by the competition of foreign states, where money is more scarce and taxation lighter, and consequently production is less expensive. The second can only be attained by a systematic emigration, conducted at the public expense, and drawing of annually an hundred or an hundred and fifty thousand of the most destitute of the community, who have not the means of transport for themselves, and, if not so removed, will permanently encumber our streets, our jails, our workhouses.