полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 69, No. 425, March, 1851

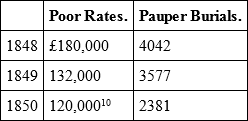

We select this as a picture of our great manufacturing towns, in which the greatest and most unbounded prosperity, so far as mere production goes, has prevailed, generally speaking, for the last thirty years; in which the custom-house duties have increased, since 1812, from £3000 a-year to £660,000, and the river dues from £4500 to £66,000 in the same period; but in which the sums expended in poor-rates and pauper burials were, in round numbers, —

10 Including buildings £87,000; for poor alone.

Indicating the deplorable destitution of multitudes in the midst of this growing wealth and unparalleled increase of manufacturing and commercial greatness. In the last year, out of 10,461 burials, no less than 2381, or nearly a fourth, were at the public expense.11

Of the wretched condition of a large class of the operatives of Glasgow – that employed in making clothes for the rest of the community – the following striking account has been given in a recent interesting publication on the "Sweating System," by a merchant tailor of the city: —

"The out-door or sweating system, by which the great proportion of their work is produced, has had a fearful debasing effect on journeymen tailors. Work is given out to a person denominated a "middle-man." He alone comes into contact with the employer. He employs others to work under him, in his own house. The workmen have no respect for him, as they have for an ordinary employer; nor has he the slightest influence over them, in enforcing proper conduct or prudent habits. On the contrary, his influence tends only to their hurt. He engages them to work at the lowest possible prices– making all the profit he can out of them. He ordinarily sets them down to work in a small, dirty room, in some unhealthy part of the city. They are allowed to work at irregular hours. Sunday, in innumerable instances brings no rest to the tailor under the sweating system; he must serve his slave-driver on that day too, even if he should go idle on the other days of the week. No use of churches or ministers to him; his calling is to produce so-called cheap clothes for the million– Sunday or Monday being alike necessary for such a laudable pursuit, though his soul should perish. Small matter that: only let the cheap system flourish, and thereby increase the riches of the people, and then full compensation has been made, though moral degradation, loss of all self-respect, and tattered rags, be the lot of the unhappy victim, sunk by it to the lowest possible degree."12

Such is the effect of the cheapening and competition system, in one of our greatest manufacturing towns, in a year of great and unusual commercial prosperity. That the condition of the vast multitude engaged in the making of clothes in the metropolis is not better, may be judged of by the fact that there are in London 20,000 journeymen tailors, of whom 14,000 can barely earn a miserable subsistence by working fourteen hours a-day, Sunday included; and that Mr Sidney Herbert himself, a great Free-Trader, has been lately endeavouring to get subscriptions for the needlewomen of London, on the statement that there are there 33,000 females of that class, who only earn on an average 4½. a day, by working fourteen hours. And the writer of this Essay has ascertained, by going over the returns of the census of 1841 for Glasgow, (Occupations of the People,) that there were in Glasgow in that year above 50,000 women engaged in factories or needle-work, and whose average earnings certainly do not, even in this year of boasted commercial prosperity, exceed 7s. or 8s. a week. Their number is now, beyond all question, above 60,000, and their wages not higher. Such is the cheapening and competition system in the greatest marts of manufacturing industry, and in a year when provisions were cheap, exports great, and the system devised for its special encouragement in full and unrestrained activity.

Facts of this kind give too much reason to believe that the picture drawn in a late work of romance, but evidently taken by a well-informed observer in London, is too well founded in fact: —

"Every working tailor must come to this at last, on the present system; and we are lucky in having been spared so long. You all know where this will end – in the same misery as 15,000 out of 20,000 of our class are enduring now. We shall become the slaves, often the bodily prisoners, of Jews, middle-men, and sweaters, who draw their livelihood out of our starvation. We shall have to fare as the rest have – ever decreasing prices of labour, ever increasing profits, made out of that labour by the contractors who will employ us – arbitrary fines, inflicted at the caprice of hirelings – the competition of women, and children, and starving Irish – our hours of work will increase one-third, our actual pay decrease to less than one-half. And in all this we shall have no hope, no chance of improvement in wages, but even more penury, slavery, misery, as we are pressed on by those who are sucked by fifties – almost by hundreds – yearly out of the honourable trade in which we were brought up, into the infernal system of contract work, which is devouring our trade, and many others, body and soul. Our wives will be forced to sit up night and day to help us – our children must labour from the cradle, without chance of going to school, hardly of breathing the fresh air of heaven – our boys, as they grow up, must turn beggars or paupers – our daughters, as thousands do, must eke out their miserable earnings by prostitution. And after all, a whole family will not gain what one of us had been doing, as yet, single-handed. You know there will be no hope for us. There is no use appealing to Government or Parliament."13

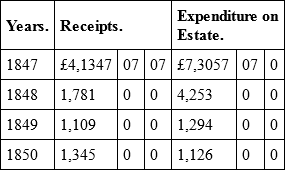

We shall only add to these copious extracts and documents one illustrative of the state to which the West Highlands of Scotland have been brought by Free Trade in black cattle and barilla, the staple of their industry: —

Price of the Estate, £163,779.

– Inverness Courier.

Couple this with the facts that, in 1850, in the face of average prices of wheat at about 40s. a quarter, the importation of all sorts of grain into Great Britain and Ireland was about 9,500,000 quarters – of course displacing domestic industry employed previous to 1846 in this production; so that the acres under wheat cultivation in Ireland have sunk from 1,048,000 in 1847, to 664,000 in 1849; and there will be no difficulty in explaining the immense influx of the destitute from the country into the great towns – augmenting thus the enormous mass of destitution, pauperism, and wretchedness, with which they are already overwhelmed.

Such is a picture, however brief and imperfect, of the social condition of our population, after twenty years of Liberal government, self-direction, and increasing popularisation, enhanced, during the last five years, by the blessings of Free Trade and a restricted and fluctuating currency. The question remains the most momentous on which public attention can now be engaged. Is this state of things unavoidable, or are there any means by which, under Providence, it may be removed or alleviated? Part of it is unavoidable, and by no human wisdom could be averted. But by far the greater part is directly owing to the selfish and shortsighted legislation of man, and might at once be removed by a wise, just, and equal system of government.

There is an unavoidable tendency, in all old and wealthy states, for riches to concentrate in the highest ranks, and numbers to become excessive in the lowest. This arises from the different set of principles which, at the opposite ends of the chain of society, regulate human conduct in the direction of life. Prudence, and the desire of elevation, are predominant at the one extremity; recklessness, and the thirst for gratification, at the other. Life is spent in the one in striving to gain, and endeavouring to rise; in the other, in seeking indulgence, and struggling with its consequences. Marriage is contracted in the former, generally speaking, from prudential or ambitious motives; in the latter, from the influence of passion, or the necessity of a home. In the former, fortune marries fortune, or rank is allied to rank; in the latter, poverty is linked to poverty, and destitution engenders destitution. These opposite set of principles come, in the progress of time, to exercise a great and decisive influence on the comparative numbers and circumstances of the affluent and the destitute classes. The former can rarely, if ever, maintain their own numbers; the latter are constantly increasing in numbers, with scarcely any other limit on their multiplication but the experienced impossibility of rearing a family. Fortunes run into fortunes by intermarriage, the effects of continued saving, and the dying out of the direct line of descendants among the rich. Poverty is allied to poverty by the recklessness invariably produced by destitution among the poor. Hence the rich, in an old and wealthy community, have a tendency to get richer, and the poor poorer; and the increase of wealth only increases this tendency, and renders it more decided with every addition made to the national fortunes. This tendency is altogether irrespective of primogeniture, entails, or any other device to retain property in a particular class of society. It exists as strongly in the mercantile class, whose fortunes are for the most part equally divided, as in the landed, where the estate descends in general to the eldest son; and was as conspicuous in former days in Imperial Rome, when primogeniture was unknown, and is now complained of as as great a grievance in Republican France, where the portions of children are fixed by law, as it is in Great Britain, where the feudal institutions still prevail among those connected with real estates.

In the next place, this tendency in old and opulent communities has been much enhanced, in the case of Great Britain, by the extraordinary combination of circumstances – some natural, some political – which have, in a very great degree, augmented its manufacturing and commercial industry. It would appear to be a general law of nature, in the application of which the progress of society makes no or very little change – that machinery and the division of labour can add scarcely anything to the powers of human industry in the cultivation of the soil – but that they can work prodigies in the manufactories or trades which minister to human luxury or enjoyment. The proof of this is decisive. England, grey in years, and overloaded with debt, can undersell the inhabitants of Hindostan in cotton manufactures, formed in Manchester out of cotton grown on the banks of the Ganges or the Mississippi; but she is undersold in grain, and to a ruinous extent, by the Polish or American cultivators, with grain raised on the banks of the Vistula or the Ohio. It is the steam-engine and the division of labour which have worked this prodigy. They enable a girl or a child, with the aid of machinery, to do the work of a hundred men. They substitute the inanimate spindle for human hands. But there is no steam-engine in agriculture. The spade and the hoe are its spindles, and they must be worked by human hands. Garden cultivation, exclusively done by man, is the perfection of husbandry. By a lasting law of nature, the first and best employment of man is reserved, and for ever reserved, for the human race. Thus it could not be avoided that in Great Britain, so advantageously situated for foreign commerce, possessing the elements of great naval strength in its forests, and the materials in the bowels of the earth from which manufacturing greatness was to arise, should come, in process of time, to find its manufacturing bear an extraordinary and scarce paralleled proportion to its agricultural population.

Consequent on this was another circumstance, scarcely less important in its effects than the former, which materially enhanced the tendency to excess of numbers in the manufacturing portions of the community. This was the encouragement given to the employment of women and children in preference to men in most manufacturing establishments – partly from the greater cheapness of their labour, partly from their being better adapted than the latter for many of the operations connected with machines, and partly from their being more manageable, and less addicted to strikes and other violent insurrections, for the purpose of forcing up wages. Great is the effect of this tendency, which daily becomes more marked as prices decline, competition increases, and political associations among workmen become more frequent and formidable by the general popularising of institutions. The steam-engine thus is generally found to be the sole moving power in factories; spindles and spinning-jennies the hands by which their work is performed; women and children the attendants on their labour. There is no doubt that this precocious forcing of youth, and general employment of young women in factories, is often a great resource to families in indigent circumstances, and enables the children and young women of the poor to bring in, early in life, as much as enables their parents, without privation, often to live in idleness. But what effect must it have upon the principle of population, and the vital point for the welfare of the working-classes – the proportion between the demand for and the supply of labour? When young children of either sex are sure, in ordinary circumstances, of finding employment in factories, what an extraordinary impulse is given to population around them, under circumstances when the lasting demand for labour in society cannot find them employment! The boys and girls find employment in the factories for six or eight years; so far all is well: but what comes of these boys and girls when they become men and women, fathers and mothers of children, legitimate and illegitimate, and their place in the factories is filled by a new race of infants and girls, destined in a few years more to be supplanted, in their turn, by a similar inroad of juvenile and precocious labour? It is evident that this is an important and alarming feature in manufacturing communities; and, where they have existed long, and are widely extended, it has a tendency to induce, after a time, an alarming disproportion between the demand for, and the supply of full-grown labour over the entire community. And to this we are in a great degree to ascribe the singular fact, so well and painfully known to all persons practically acquainted with such localities, that while manufacturing towns are the places where the greatest market exists for juvenile or infant labour – to obtain which the poor flock from all quarters with ceaseless alacrity – they are at the same time the places where destitution in general prevails to the greatest and most distressing extent, and it is most difficult for full-grown men and women to obtain permanent situations or wages, on which they can maintain themselves in comfort. Their only resource, often, is to trust, in their turn, to the employment of their children for the wages necessary to support the family. Juvenile labour becomes profitable – a family is not felt as a burden, but rather as an advantage at first; and a forced and unnatural impulse is given to population by the very circumstances, in the community, which are abridging the means of desirable subsistence to the persons brought into existence.

Lastly the close proximity of Ireland, and the improvident habits and rapid increase of its inhabitants, has for above half a century had a most important effect in augmenting, in a degree altogether disproportioned to the extension in the demand for labour, the numbers of the working classes in the community in Great Britain. Without stopping to inquire into the causes of the calamity, it may be sufficient to refer to the fact, unhappily too well and generally known to require any illustration, that the numbers of labourers of the very humblest class in Ireland has been long excessive; and that any accidental failure in the usual means of subsistence never fails to impel multitudes in quest of work or charity, upon the more industrious and consequently opulent realm of Britain. Great as has been the emigration, varying from 200,000 to 250,000 a-year from Ireland, during the last two years to Transatlantic regions, it has certainly been equalled, if not exceeded, by the simultaneous influx of Irish hordes into the western provinces of Britain. It is well known14 that, during the whole of 1848, the inundation into Glasgow was at the rate of above 1000 a-week on an average; and into Liverpool generally above double the number. The census now in course of preparation will furnish many most valuable returns on this subject, and prove to what extent English has suffered by the competition of Irish labour. In the mean time, it seems sufficient to refer to this well-known social evil, as one of the causes which has powerfully contributed to increase the competition among the working-classes, and enhance the disproportion between the demand for, and the supply of, labour, which with few and brief exceptions has been felt as so distressing in Great Britain for the last thirty years.

Powerful as these causes of evil undoubtedly were, they were not beyond the reach of remedy by human means – nay, circumstances simultaneously existed which, if duly taken advantage of, might have converted them into a source of blessings. They had enormously augmented the powers of productive industry in the British Empire; and in the wealth, dominion, and influence thereby acquired, the means had been opened up of giving full employment to the multitudes displaced by its boundless machinery and extended manufacturing skill. Great Britain and Ireland enjoyed one immense advantage – their territory was not merely capable of yielding food for the whole present inhabitants, numerous and rapidly increasing as they were, but for double or triple the number. The proof of this is decisive. Although the two islands had added above a half to their numbers between 1790 and 1835, the importation of foreign grain had been continually diminishing; and in the five years ending with 1835, they had come to be on an average only 398,000 quarters of grain and flour in a year – being not a hundredth part of the whole subsistence of the people. Further, agriculture in Great Britain, from the great attention paid to it, and the extended capital and skill employed in its prosecution, had come to be more and more worked by manual labour, and was rapidly approaching – at least, in the richer districts of the country —the horticultural system, in which at once the greatest produce is obtained from the soil, and the greatest amount of human labour is employed in its cultivation; and in which the greatest manufacturing states of former days, Florence and Flanders, had, on the decay of their manufacturing industry, found a never-failing resource for a denser population than now exists in Great Britain.

But, more than all, England possessed, in her immense and rapidly-increasing colonies in every quarter of the globe, at once an inexhaustible vent and place of deposit for its surplus home population, the safest and most rapidly-increasing market for its manufacturing industry, and the most certain means, in the keeping up the communication between the different parts of so vast a dominion, of maintaining and extending its maritime superiority. This was a resource unknown to any former state, and apparently reserved for the Anglo-Saxon race, whom such mighty destinies awaited in the progress of mankind. The forests of Canada, the steppes of Australia, the hills of New Zealand, the savannahs of the Cape, seemed spread out by nature to receive the numerous and sturdy children of the Anglo-Saxon race, whom the natural progress of opulence, the division of labour, the extension of machinery, and the substitution of female and juvenile for male labour, were depriving of employment in their native seats. In the colonies, manual labour was as much in demand as it was redundant in the parent state. No machinery or manufactures existed there to displace the arm of the labourer's industry; the felling of the forest, the draining of the morass, the cultivation of the wild, chained the great majority of the human race to agricultural employments, for generations and centuries to come. Even the redundant number and rapid increase of the Celtic population in Ireland could not keep pace with the demand for agricultural labour in our Transatlantic dominions. The undue preponderance of the female sex, felt as so great and consuming an evil in all old and wealthy cities, might be rendered the greatest possible blessing to the infant colonies, in which the greatest social evil always experienced is the excessive numbers of the male sex. All that was required was the removal of them from the overburdened heart to the famishing extremities of the empire; and this, while it relieved the labour, promised to afford ample employment to the national navy. The magnitude of this traffic may be judged of by the fact that the 212,000 emigrants who arrived at New York in the year 1850 were brought in 2000 vessels. At the same time the rapid growth of the colonies, under such a system, would have furnished a steady market for the most extensive manufacturing industry at home, and that in a class of men descended from ourselves, imbued with our habits, actuated by feeling our wants, and chained by circumstances, for centuries to come, to the exclusive consumption of our manufactures. What the magnitude of this market might have been may be judged of by the fact that, in the year 1850, Australia and New Zealand, with a population which had not yet reached 250,000 souls, took off in the year 1850 £2,080,364 of our manufactures, being at the rate of £8 a-head; while Russia, with a population of 66,000,000, only took off £1,572,593 worth, being not 6d. a-head.15

The social evils which at first sight appear so alarming, therefore, in consequence of the extension of our manufacturing population, and the vast increase of our wealth, were in reality not only easily susceptible of remedy, but they might, by a wise and paternal policy, alive equally to the interests represented and unrepresented of all parts of the empire, have been converted into so many sources of increasing prosperity and durable social happiness. All that was required was to adopt a policy conducive alike to the interests of all parts of our varied dominions, but giving no one an undue advantage over the other; legislating for India as if the seat of empire were Calcutta, for Canada as if it were Quebec, for the West Indies as if it were Kingston. "Non alia Romæ alia Athenæ," should have been our maxim. Equal justice to all would have secured equal social happiness to all. The distress and want of employment consequent on the extension of machinery, and the growth of opulence in the heart of the empire, would have become the great moving power which would have overcome the attachments of home and country, and impelled the multitudes whom our transmarine dominions required into those distant but still British settlements, where ample room was to be found for their comfort and increase, and where their rapidly increasing numbers would have operated with powerful effect, and in a geometrical ratio, on the industry and happiness of the parent state. Protection to native industry at home and abroad was all that was required to bless and hold together the mighty fabric. So various and extensive were the British dominions, that they would soon have arrived at the point of being independent of all the rest of the world. The materials for our fabrics, the food for our people, were to be had in abundance in the different parts of our own dominions. We had no reason to fear the hostility or the stopping of supplies from any foreign power. The trade of almost the whole globe was to Great Britain a home trade, and brought with it its blessings and its double return, at each end of the chain.

These great and magnificent objects, which are as clearly pointed out by Providence as the mission of the British nation – and which the peculiar character of the Anglo-Saxon race so evidently qualified it to discharge – as if it had been declared in thunders from Mount Sinai, were in a great degree attained, though in an indirect way, under the old constitution of England; and accordingly, while it lasted, and was undisturbed in its action by local influences in the heart of the empire, distress was comparatively unknown at home, and disaffection was unheard of in our distant settlements. The proof of this is decisive. The tables already given in the former part of this paper demonstrate when distress at home and sedition abroad seriously set in, when emigration advanced with the steps of a giant, and crime began to increase ten times as fast as the numbers of the people – and the poor-rates, despite all attempts to check them by fresh laws, threatened to swallow all but the fortunes of the millionnaires in the kingdom. It was after 1819 that all this took place. Previous to this, or at least previous to 1816, when the approaching great monetary change of that year was intimated to the Bank, and the contraction of the currency really began, distress at home was comparatively unknown, and the most unbounded loyalty existed in our colonial settlements in every part of the world. But from that date our policy at home and abroad underwent a total change. Everything was changed with the change in the ruling influences in the state. The words of the Christian bishop who converted Clovis were acted upon to the letter – "Brulez ce que vous avez adoré; adorez ce que vous avez brulé." The moneyed came to supplant the territorial aristocracy, the interests of realised capital to prevail over those of industry and wealth in the course of formation. The Reform Bill confirmed and perpetuated this change, by giving the moneyed class a decided majority of votes in the House of Commons, and the House of Commons the practical government of the country. From that moment suffering marked us for her own. Misery spread in the heart of the empire; many of its most flourishing settlements abroad went to ruin; and such disaffection prevailed in all, that Government, foreseeing the dissolution of the empire, has already taken steps to conceal the fall of the fabric by voluntarily taking it to pieces.