полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 69, No. 424, February 1851

"The aggregate inward entries during the ten months ended the 5th of November 1849, were 5,081,592 tons, of which 3,651,589 were British, and 1,430,003 foreign. During the corresponding ten months ending the 5th of November of the present year, the aggregate entries are 5,114,064 tons, the British being 3,365,033, and the foreign 1,749,031. Thus, comparing the first ten months after the repeal of the Navigation Laws with the corresponding ten months of the preceding year, when those laws were in operation, we find that British tonnage has decreased within this brief period no less than 286,556, or 8-1/10 per cent, while foreign tonnage has increased to the enormous extent of 319,028 tons, or 22-3/10 per cent, the whole entries having advanced only 32,472 tons – thus showing that our maritime commerce has not been augmented in any appreciable degree by the alteration, but that it has simply changed hands. The foreigner has taken what we have madly surrendered. I may add, that never was the state, and never were the prospects, of shipowners so gloomy. Freights in all parts of the world are unprecedentedly low, and, for the first time within my recollection, ships are actually returning from the British West Indies in ballast.

"Could I regard the whole subject with less of humiliating apprehension for my country, I might derive satisfaction from the confirmation of many predictions on which I have formerly ventured, afforded by an analysis of the return from which the melancholy result I have exhibited is taken. Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Prussia, and Germany – countries whose rivalry you have repeatedly derided as undeserving of attention – have increased in the ten months from 502,454 tons to 796,200 tons, or 58-4/10 per cent. But I forbear. While all Europe bristles with bayonets, the loom and the spindle seem to be regarded as the chosen defences of this now the most unwarlike nation on the face of the earth. Wellington, and Ellesmere, and Napier have in vain essayed to arouse England to solicitude for her national defences; and till some imminently impending alarm shall awaken my countrymen to a sense of the insecurity in which they are unconsciously reposing, I almost dread they will accept the unworthy advice recently tendered to them by the unadorned oracle of Free Trade, to run every risk rather than incur any expense. It is thus that, under the illusory expectation of the most infinitesimally minute reduction in the freight of imported commodities, the hazard of leaving our navy unmanned is overlooked or disregarded."

In the single harbour of Liverpool, the decrease of British shipping, in the year 1850, has been no less than 100,000 tons; while the foreign has swelled from 56,400 to 126,700.14 If such has been the result in less than one year, what may be anticipated if the system continues three or four years longer? It is quite evident that the foreign tonnage employed in conducting our trade will come to exceed the British, and then, of course, our independence and maritime superiority are alike at an end.

The Free-Traders, in answer to this appalling statement, say that the entries outward exhibit a different and less unfavourable result. Without referring to the authority of Mr Huskisson, who stated what is well-known to all men practically engaged with the subject, that the outward entries afford no correct data for judging of trade returns, it may be sufficient to remark that the difference is mainly owing, in the present instance, to the prodigious multitude of our emigrants to America, the shipping employed in conveying whom is estimated at 240,000 tons. The Free-Traders first, by their final measures, drive some 300,000 of our industrious inhabitants out of the country annually, in quest of the employment which they have lost at home, and then they rest on the tonnage required to convey them away, in order to conceal the effect of Free Trade in shipping on our mercantile marine! They are welcome to the whole benefit which they can derive from the double effect of Free Trade, first on our people, and then on our shipping.

These considerations become the more forcible when it is considered, in the third place, what immediate and imminent risk there is that either our principal colonies will ere long declare themselves independent, or that they will be abandoned without a struggle by our Free-Trade rulers. Now, the tonnage between Great Britain and Canada is about 1,200,000 tons, and to the West Indies somewhat above 170,000. Fourteen hundred thousand British tons are taken up with our trade to these two colonies alone; and if they become independent states, that tonnage will, to the extent of more than a half, slip from our grasp – as they have the materials of shipbuilding at their door, which we have not. Eight or nine hundred thousand tons will by that change at once be severed from the British Empire and added to the foreign tonnage employed in carrying on our trade, which is now about 2,200,000 tons. That will raise it to above 3,000,000 tons, or fully a half of our whole tonnage, foreign and British – which is, in round numbers, about 6,000,000 tons. The intention of Government to abandon our colonies to themselves has been now openly announced. Earl Grey's declaration of his resolution to withdraw all our troops, except a mere handful, from Australia, is obviously the first step in the general abandonment of the colonies to their own resources, and, of course, their speedy disjunction from the British Empire. As the separation of Canada and the West Indies is an event which may ere long be looked for – not less from the universal discontents of the colonies, who have lost by Free Trade their only interest in upholding the connection with the British Empire, than from the growing disinclination of our Free Trade rulers to continue much longer the burdens and expense consequent on their government – it is evident that, the moment it happens, the foreign ships employed in carrying on our trade will outnumber the British. From that moment the nursery for our seamen, and with it the means of maintaining our maritime superiority and national independence, are at an end. And as this separation will, to all human appearance, take place the moment that we are involved in a European war – which, with the aggressive policy of our Foreign Minister, may any day be looked for – this is perhaps the most immediate and threatening danger which menaces the British Empire.

When the magnitude and variety of the perils which Free Trade and the cheapening system have brought upon the British empire are taken into consideration, it may appear extraordinary that the foreign powers, who are perfectly aware of it all, do not at once step forward and secure for themselves the rich prize which we so invitingly tender to their grasp. But the reason is not difficult to be discerned. They know what England once was, and they see whither, under the new system, she is tending. They anticipate our subjugation, or at least our abrogation of the rank and pretensions of an independent power, at no distant period, from our own acts, without their interfering in the matter at all. They are fearful, if they move too soon, of committing the same fault which the Pope has recently done, on the suggestion of Cardinal Wiseman. They are afraid of opening the eyes of the nation, by any overt act, to the dangers accumulating around them, before it is so thoroughly debilitated by the new system that any resistance would be hopeless, and therefore will never be attempted. They hope, and with reason, to see us ruined and cast down by our own acts, without their firing a shot. Their feeling is analogous to Napoleon's on the morning of the battle of Austerlitz, when the Allies were making their fatal cross-march in front of the heads of his columns, and exposing their flank to his attack. When urged by his generals to give the signal for an immediate advance, he replied – "Wait! when the enemy is making a false movement, which will prove fatal if continued, it is not our part to interrupt him in it."

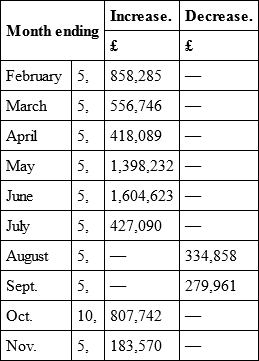

What, then, is the advantage which the Free-Traders have to set off against these obvious and appalling dangers, past, present, and to come, with which their policy is attended? It is this, and this only – that the manufacturing towns are prosperous, and that our exports are increasing. They point with exultation to the following statement: —

"The aggregate value of our exports, during the first ten months of the present year, has been L.55,038,206, against L.49,398,648 in the like period of 1849, showing an increase of L.5,639,558, which has occurred in the following order:

– Times, Nov. 10."

Now, let it be supposed that this increase, which will amount to less than L.7,000,000 in our exports in the whole year, is all to be set down to the credit of Free Trade. Let us suppose that Californian gold, which has given so unparalleled a stimulus to America, and the lowering the discounts of the Bank of England to 2½ per cent – which has done so much, as it always does, to vivify industry and raise prices at home – and the pacification of Germany by Muscovite influences or bayonets, which have again, after the lapse of two years, opened the Continental markets to our produce, have had nothing at all to do with this increase in our exports, – what, after all, does it amount to, and what, on striking the balance of profit and loss of Free Trade, has the nation lost or gained by its adoption?

It has increased our exports by L.7,000,000 at the very utmost; and as the total produce of our manufactures is about L.180,000,000, this is an addition of a twenty-fifth part. It has made four or five hundred thousand persons employed in the export manufactures prosperous for the time, and increased, by five or six hundred thousand pounds in the last year, the incomes of some eighty or a hundred mill-owners or millionnaires.

Per contra. 1. It has lowered the value of agricultural produce of every kind fully twenty-five per cent, and that in the face of a harvest very deficient in the south of England. As the value of that produce, prior to the Free-Trade changes, was about L.300,000,000 a-year, it has cut L.75,000,000 off the remuneration for agricultural industry over the two islands.

2. It has cut as much off the funds available to the purchase of articles of our manufacture in the home market; for if the land, which pays above half the income tax, is impoverished, how are the purchasers at home to find funds to buy goods?

3. It has totally destroyed the West Indies – colonies which, before the new system began, raised produce to the value of L.22,000,000, and remitted at least L.5,000,000 annually, in the shape of rent, profits, and taxes, to this country.

4. It has induced such ruin in Ireland, that the annual emigration, which chiefly comes from that agricultural country, last year (1849) reached 300,000 souls, and this year, it is understood, will be still greater.15 This is as great a chasm in our population as the Moscow retreat, or the Leipsic campaign, made in that of France; but it excites no sort of attention, or rather the pressure of unemployed labour is felt to be so excessive, that it is looked on rather as a blessing. The Times observes, on January 1, 1851: —

"We see the population of Ireland flowing off to the United States in one continuous and unfailing stream, at a rate that in twenty years, if uninterrupted, will reduce them to a third of their present numbers. We see at the same time an increasing emigration from this island. England has so long been accustomed to regard excess of population as the only danger, that she will be slow to weigh as seriously as perhaps she ought this rapid subtraction of her sinew and bone, and consequent diminution of physical strength. It is impossible, however, that so considerable a change should be attended with unmixed advantage, or that human forethought should be able to compass all the results. The census of next spring may invite attention to a subject, the very magnitude of which may soon command our anxiety."

5. It has totally ruined the West Highlands of Scotland, which depend on two staples – kelp and black cattle – the first of which has been destroyed by free trade in barilla, and the second ruined by free trade in cattle, for the benefit of our manufacturing towns, and sent their cottars in starving bands to Glasgow, already overwhelmed by above L.100,000 a-year of poor-rates.

6. It has so seriously affected the internal resources of the country, that, with a foreign trade prosperous beyond what has been seen since 1845, the revenue is only L.165,000 more than it was in the preceding year, which was one of great depression; and the last quarter has produced L.110,000 less than the corresponding quarter of 1849.

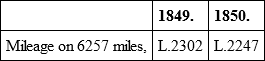

7. It has so lowered the incomes of people in the country, that although the number of travellers by railways has greatly increased, and the total receipts of the lines have been swelled by L.1,700,000 since last year, the mileage has decreased-proving, that the general traffic of the country bears no adequate proportion to its railway lines. It stands thus, —

– Times.

which is a fall of L.55 a mile in the midst of our boasted prosperous export trade.

Such are the advantages, in consideration of which the nation has embarked on a course of policy which so evidently, and in so many ways, threatens our independence. It is class government which has done it all – the determination to make the sovereign worth two sovereigns, and a day's labour to the poor man worth one shilling to him instead of two, which has induced dangers in every quarter, which threaten the existence of Great Britain. Why is it that we are constrained – though Government are perfectly aware of the danger, and the Duke of Wellington has repeatedly pointed it out – to have a military and naval force evidently incommensurate to the wants of our vast empire, and unable to defend it from the hostility which our foreign policy does so much to provoke? Simply because we have surrendered the government of the country to a moneyed oligarchy, who are resolved, coute qui coute, to cheapen everything, because it enhances the value of their realised wealth, and because the measures of that oligarchy have cut down Queen Victoria's income from £100,000,000 – as it might have been, and is now, in real weight upon the country16– to £50,000,000; just as they have reduced the income of the poor needlewomen from 9d. a-day to 4-1/2d. Why is it that we are constrained, openly and avowedly, to abandon our colonies to their own resources? Only because the cheapening system and Free Trade have so paralysed and weakened our resources, that, like the Romans, if we would protect at all the heart of the empire, we must forthwith abandon its extremities.

Why are we evidently and undeniably losing the empire of the seas, by the rapid and portentous increase of the foreign and decline of the English shipping, in carrying on our own trade? Only because freights must, it is thought, be cheapened as well as everything else; and the independence of the country is a trifling consideration to a fall of a farthing in the pound, in the transport of some articles, for the benefit of the Manchester trader. Why are the West Indies utterly ruined, and the annual importation of slaves into Cuba and Brazil doubled,17 and discontent so universally spread through our colonies, that beyond all doubt, in the first reverse, they will break off from the mother country, if not previously thrown off by it? Merely to carry out the dogma of Free Trade, and lower sugar, watered by the blood of the slaves, a penny or twopence a pound to the British consumer. Why have we brought 7,000,000 of our people, in three years, to depend for their daily food on foreign supplies, and put ourselves entirely at the mercy of the two states from which nearly all that food comes? Only to enrich the Manchester manufacturers, and appease the cry for cheap bread, by enabling them to beat down the wages of labour from 1s. 6d. to 1s. a-day. Why are poor-rates – measured in the true way, by quarters of grain – heavier in this year of boasted prosperity than they were in any former year of admitted adversity? Because, in every department of industry, we have beat down native by letting in a flood of foreign industry. Why are 300,000 industrious citizens annually driven into exile, and Ireland threatened with a depopulation the most rapid and extraordinary which has been witnessed in the world since the declining days of the Roman empire? Because we would lower wheat from 56s. to 39s. a quarter; and thereby we have extinguished the profits of cultivation in a portion of our empire containing 8,000,000 of inhabitants, but so exclusively agricultural that its exports of manufactures are only £230,000 a-year. It is one principle – the cheapening system – devised by the moneyed and manufacturing oligarchy, and calculated for their exclusive benefit, which has done the whole.

Is there, then, no remedy for these various, accumulating, and most threatening evils? Must we sit down with our hands across, supinely witnessing the progressive dangers and certain ultimate destruction of the empire, merely because the measures inducing all these perils are supported by the moneyed and manufacturing oligarchy who have got the command of the House of Commons? We are far from thinking that this is the case; but if we would avert, or even mitigate our dangers, we must set ourselves first to remedy the most pressing. Of these, the most serious, beyond all question, are to be found in our unprotected state, – for they may destroy us as a nation in a month, after some fresh freak of Lord Palmerston's has embroiled us with some of the great European powers. In regard to other matters, and the general commercial policy, the danger, though not the less real, is not so immediate, and experience may perhaps enlighten the country before it is too late. But it is otherwise with our external dangers: they are instant and terrible. The means of resisting them are perfectly simple – they will be felt as a burden by none; on the contrary, they are calculated, at the same time that they provide for our national defence, to mitigate the greater part of the domestic evils under which the people labour.

Government tell us that they have a surplus of L.3,000,000 this year in their hands. We hope it is so, and that it will not prove, like other surpluses, greater on paper than in reality. But let it be assumed that it is as large as is represented. That surplus, judiciously applied, would save the country! It would raise our armaments to such a point as, with the advantages of our insular situation, and long-established warlike fame, would prevent all thoughts of invasion on the part of our enemies. It would give us 100,000 regular troops, with those we already have – 100,000 militia, occasionally called out – and 25 ships of the line, with those already in commission, to defend the British shores. It is true, the continuance of the Income Tax cannot be relied on – nor should the country submit to it any longer; for a tax which is paid exclusively by 147,000 persons out of 28,000,000, is so obviously unjust, that its further retention is probably impossible. Additional direct taxation upon the affluent classes is obviously out of the question, for the chasms made in the incomes of those depending on land, who pay three-fourths of it, are such that it would prove totally unproductive. What, then, is to be done to uphold the public revenue at its present amount, or even prevent its sinking so as to increase instead of diminishing our helpless and unprotected state? An obvious expedient remains. Imitate the conduct of America and Prussia, France and Russia, and all countries who have any regard either to their national independence, or the social welfare of their inhabitants. Lay a moderate duty upon all importations, whether of rude or manufactured articles. In America it is 30 per cent, and constitutes nearly their sole source of revenue: in Prussia it is practically 40 or 50 per cent. By this means nearly half the tax is paid by foreigners– for competition forces them to sell the articles taxed cheaper than their ordinary price, with the addition of the tax. It is spread over so vast a surface among consumers, that its weight is not felt; being mixed up with the price of the article sold, its weight is not perceived. We pay in this way half the taxes of America, Germany, and all the countries to whom we chiefly export our manufactures. Let us return them the compliment, and adopt a system which will make them pay the half of ours. The whole, or nearly the whole, of the Income Tax, which now produces L.5,400,000 a-year, would by this change be spent in increased purchases in the home market, and sensibly relieve its sinking state. This change would at once obviate our external dangers – for it would enable Government, without sensibly burdening the country, to maintain the national armaments on such a scale as to bid defiance to foreign attack. We shall see in our succeeding paper whether it would not, at the same time, be an effectual remedy, and the only one that would be practicable, to the most serious part of our domestic evils.

CURRAN AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES. 18

A noble land lies in desolation. Years pass over it, leaving its aspect only more desolate; the barbarian takes possession of the soil, or the outcast makes it his place of refuge. Its palaces are in ruins, its chieftains are in the dust; its past triumphs are regarded as the exaggerations of romance, or the fond fantasies of fable. At length a man of intelligence and vigour comes, delves into the heart of the soil, breaks up the mound, throws aside the wrecks of neglect and time, opens to us the foundations of palaces, the treasure-chambers of kings, the trophies of warriors, and gives the world the memorials of a great people in the grave.

All analogy must be imperfect in detail; and we have no desire to insist on the perfection of our analogy between the Golden Head of the East, and the little kingdom whose fallen honours are recorded in the volume before us. But, if Ireland is even now neither the nominis umbra which the Assyrian empire has been for so many ages, nor the Irish legislature the heir of the fierce and falcon-eyed council which sleeps in the sepulchres of Nineveh, there is something of a curious relationship in the adventurous industry which has so lately exhumed the monuments of Eastern grandeur, and the patriotic reminiscence which has retrieved the true glories of the sister country, the examples of her genius, from an oblivion alike resulting from the misfortunes of the Land and the lapse of Time.

Nor are we altogether inclined to admit the inferiority of the moral catastrophe of the Island to the physical fall of the Empire. If there be an inferiority, we should place it on the side of the Oriental throne. To us, all that belongs to mind assumes the higher rank; the soil trodden by the philosopher and the patriot, the birthplace of the poet and the orator, bears a prouder aspect, is entitled to a more reverent homage, and creates richer recollections in the coming periods of mankind, than all the pomp of unintellectual power. There would be to us a stronger claim in the fragments of an Athenian tomb, or in the thicket-covered wall of a temple in the Ægean, than in all the grandeurs of Babylon.

It is now fifty years since the parliament of Ireland fell; and, in that period, there has not been a more disturbed, helpless, and hopeless country than Ireland, on the face of the earth. Nor has this calamity been confined to the lower orders; every order has been similarly convulsed. The higher professions have languished and lost their lustre; the Church has been exposed to a struggle for life; the nobility have given up the useless resistance to difficulties increasing round them from hour to hour; the landed interest is supplicating the Court of Encumbered Estates to relieve it from its burthens; the farmers are hurrying, in huge streams of fugitives, from a land in which they can no longer live; and the tillers of the ground, the serfs of the spade, are left to the dangerous teaching of an angry priesthood, or to the death of mingled famine and pestilence. A cloud, which seems to stoop lower day by day, and through which no ray can pierce, at once chills and darkens Ireland.