полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 69, No. 424, February 1851

"A ship," says Admiral Bowles, "is required to relieve another for foreign service. She is selected, reported ready for commission, the captain and officers are appointed, and then volunteers are advertised for. They come in slowly and uncertainly. If the ship is a large one, the men will not enter until the heaviest part of the work of fitting is completed: the equipment proceeds slowly and carelessly, because energy and rapidity are impracticable; but even then, those who enter first feel they are unfairly worked, and the seeds of discontent and desertion are sown at the very commencement of their service.

"Three, or sometimes four, months thus pass away, before the ship's complement is complete; and, in the meanwhile, little progress is made in discipline or instruction. She at last sails for her destination, and relieves a ship which, having been three or four years on active service is, or ought to be, in a high state of efficiency; but on its arrival in England it is dismantled, the officers and crew are paid off and discharged, and we thus proceed, on the plan of perpetually creating and as perpetually destroying, what we have with so much labour and expense endeavoured to obtain – an effective ship of war."8

Captain Plunkett adds his valuable testimony to the same effect: —

"Voluntary enlistment may be considered entirely inapplicable to cases of emergency. There are no means of calculating how long ships would be manning, if, as would necessarily happen in cases of emergency, their crews were not increased by men recently paid off from other ships. In peace, there are usually as many ships paid off as commissioned in a year; and thus the men who leave one ship join another. But, even with this aid, the average time occupied by general line-of-battle ships in completing their crews, we find to have been above five months. In 1835-6, when we commissioned several ships of line at once, they were six months waiting for seamen, and were then very ill manned. We may safely suppose that, were ten sail of the line commissioned at this moment, and did circumstances not admit of paying others off, we should not see them manned in less than eight months. We may therefore say that, for any case of emergency, simple volunteering will fail, as it always has failed. We may expedite the material fitting of a fleet; we may move ships about our harbours, put their masts in, and call them 'demonstration' or 'advance ships!' we may even fit them for sea – for the dockyard men can do all that – but, when fitted, there they must remain for months waiting for seamen. Foreign powers are quite aware of this, for it is the duty of their consuls at our ports to inform their governments, and they must laugh at the demonstration by which John Bull plays a trick upon – Himself!

"It is a matter of official avowal, and, we may add, of personal and painful recollection, that, in 1840, we were unable to collect a few hundred seamen to make a show of preparation… When England was vainly trying to scrape together a few hundred seamen, France had (in compagnies permanentes) upwards of 3000 ready in the Atlantic ports, and probably not less at Toulon.

"It is a fact as surprising as it is discreditable to England, that Russia could send thirty sail of the line to sea before England could send three.

"It is scarcely an exaggeration to say, we might build a ship in the time required to man one."

We add not a word of comment on these admirable passages. Further illustration were worse than useless, after such words coming from such quarters.

It is often said that all fears of invasion are ridiculous, after the failure of Napoleon, who had 130,000 of the finest troops in the world to effect it. The Times, with its usual ability, makes the most of this argument. We accept the challenge: and, if we are not much mistaken, that able journal will have no reason to congratulate itself on having referred to that period for support of its argument: —

1. The regular land forces of France at that period were 450,000 men: about the same as they are now. But now that Power has, in addition, 2,000,000 well-trained National Guards in arms, which, by rendering her territory wellnigh unassailable, leaves her whole regular force available for foreign expedition.

2. England had then 160,000 regular troops on foot, including 30,000 of the army of reserve, raised in the preceding years, of whom about 100,000 were in the British Islands. In 1808, the Duke of York reported to Government that, without detriment to any necessary home service, 60,000 regulars could be spared for the Peninsula; and in 1809 she had 80,000 in active warfare – viz., 40,000 at Walcheren, 30,000 in Spain, and 10,000 in Sicily.

3. In addition to this, she had 80,000 militia, quite equal to troops of the line, in Great Britain and Ireland, besides 300,000 volunteers in arms, tolerably drilled and full of spirit.

4. She had 83 ships of the line in commission, and 230 in all the royal dockyards, and 508 vessels of war bore the royal flag.

5. She had a system of impressment in active operation, which in effect gave the Admiralty the command, on an emergency, of the whole sailors in the mercantile navy of Great Britain, as they successively came into harbour: and the magnitude of the royal navy was such, and its attractions – especially the hopes of prize-money and glory – so powerful, that the sailors of the fleet were as much a standing force as Napoleon's grenadiers.

6. Austria and Russia were then in close alliance, offensive and defensive, with Great Britain, and 80,000 Muscovites, under Kutusoff, were hastening through Poland and Moravia to join 90,000 Austrians, who were on the Inn, threatening to invade Bavaria.

7. So instant was the danger, and so pressing the approach of a contest with the two greatest military powers on the Continent, that Napoleon was obliged to count not only by weeks but by days; and he had only just time enough to close the war, as he himself said, by "a clap of thunder on the Thames, before he would be called on to combat for his existence on the Danube."

Such were the circumstances under which Napoleon then undertook his long meditated and deeply laid project for the invasion and conquest of Great Britain. His plan was to decoy Lord Nelson away to the West Indies by a feigned expedition of the combined Toulon and Cadiz fleets, and for them suddenly to return, join the Ferrol squadron, pick up those of Rochefort and l'Orient, unite with that of Brest, and with the united force, which would be sixty sail of the line, proceed into the Channel, where it was calculated there would only be twenty or twenty-five to oppose them; and, with this overwhelming force, cover the embarkation of the 130,000 men whom he had collected on the coast of the Channel. The plan was not original on the part of Napoleon, though he had the whole merit of the organisation of the stupendous armament which was to carry it into execution. The design was originally submitted, in 1782, by M. de Bouillé to Louis XVI., and Rodney's victory alone prevented it from being attempted at that time. France's designs in this respect are fixed and unalterable: they were the same under the mild and pacific Louis as the implacable Napoleon, and suggested as ably by the chivalrous and loyal-hearted de Bouillé, the author of the flight of the Royal family to Varennes, as by the regicide Talleyrand, or the republican Décrès.9

Such was Napoleon's plan, formed on that of M. de Bouillé; and, vast and complicated as it was, it all but succeeded. Indeed, its failure was owing to a combination of circumstances so extraordinary that they can never be expected to recur again; and even these are to be ascribed rather to the good providence of God, than to anything done by man to counteract it.

Nelson's fleet of ten line-of-battle ships pursued the combined fleet of twenty from Cadiz to the West Indies; but they had four weeks the start of him: and upon arriving there in the beginning of June, he received intelligence that they had set sail ten days before for Europe. Instantly divining their plan, he – without losing an hour – despatched several fast-sailing brigs to warn the Admiralty of their approach. One of these, the Curieux, which bore the fortunes of England on its sails, outstripped all its competitors, and even outsailed the combined fleet, so as to arrive at Portsmouth on the 9th July. Without losing an hour, the Admiralty sent orders by telegraph to Admiral Calder to join the Rochefort blockading squadron, and stand out to sea, in order to intercept the enemy on his return to the European seas. He did so; and with fifteen sail of the line met the combined fleet of twenty, on the 15th July: engaged them, took two ships of the line, and drove the fleet back into Ferrol; where, however, he was too weak to blockade them, as their junction with the squadron there raised their force to thirty ships of the line.

Though this was a severe check, it did not altogether disconcert Napoleon. He sent orders to Villeneuve to set sail from Ferrol, and join the Rochefort and Brest squadrons which were ready to receive him, and which would have raised the combined fleet to fifty-five line-of-battle ships, then to make straight for the Channel, where Napoleon, with one hundred and thirty thousand men, and fifteen hundred gun-boats and lesser craft, lay ready to embark. On the 21st August, the Brest squadron, consisting of twenty-one sail of the line, under Gantheaume, stood out to sea. Every eye was strained looking to the south, where Villeneuve with thirty-five line-of-battle ships, was expected to appear. What prevented the junction, and defeated this admirably laid plan, which had thus obtained complete success so far as it had gone – for Nelson was still a long way off, his fleet having been wholly worn-out by their long voyage, and obliged to go into Gibraltar to refit? It was this: Villeneuve set sail from Ferrol with 29 sail of the line, on the 11th August, but instead of proceeding to the north – in conformity with his orders – to join Gantheaume off Brest, he steered for Cadiz, which he reached in safety on the 21st of August, the very day on which he had been expected at Brest, without meeting with Sir Robert Calder, who had fallen back into the Bay of Biscay. For this disobedience of orders, Napoleon afterwards brought Villeneuve to a court-martial, by which he was condemned.

This unaccountable disobedience of orders entirely defeated Napoleon's scheme, for Austria was now on, the verge of invading Bavaria. He accordingly at once changed his plan; and, as he could no longer hope for a naval superiority in the Channel, before the Austrian invasion took place, directed all his forces to repel the combined Austrian and Russian forces in Bavaria and Italy. On September 1, his whole army received orders to march from the heights of Boulogne to the banks of the Danube. On the 20th October, Mack defiled, with thirty thousand men as prisoners before him, on the heights of Ulm; and on the day after – October 21 – Nelson defeated Villeneuve at Trafalgar, took nineteen ships of the line, and ruined seven more. Between that battle and the subsequent one of Sir R. Strachan, thirty ships of the line were taken or destroyed; all hope of invasion for the remainder of the war was at an end; and "ships, colonies, and commerce" had irrevocably passed to Napoleon's enemies.

Such was the extraordinary and apparently providential combination of circumstances which defeated this great plan of Napoleon for the invasion of this country – a plan which, he repeatedly said, was the best combined and most deeply laid of any he had ever formed in his life. Its failure was owing to accident, or some overruling cause which cannot be again relied on. Had the Curieux not made the shortest passage ever then known, from Antigua – twenty-four days; had Villeneuve reached the Channel unexpectedly on the 20th or 21st July, as he would have done but for its arrival – had he even sailed for Brest on the 11th August, as ordered, instead of to Cadiz, the invasion would in all human probability have taken place. What its result would have been is a very different question. With a hundred and eighty thousand regular troops and militia in arms in the British Islands, besides three hundred thousand volunteers, the conflict must at least have been a very desperate one. But what would it be now, when the French and Russians have greater land forces to invade us; when their naval superiority, at least in the outset of the contest, would be much more decisive; and, with a much more divided and discontented population at home, we could only – at the very utmost – oppose them with fifty thousand effective men in both islands, in the field.

It is often said by persons who know nothing of war, either by study or experience, that "if the French invaded us, we would all rise up and crush them." Setting aside what need not be said to any man who knows anything of the subject – the utter inadequacy of an unarmed, untrained, and undisciplined body of men, however individually brave, to repel the attack of a powerful regular army – we shall by one word settle this matter of the nation rising up. It would rise up, and we know what it would do. The most influential part of it, at least in the towns, who now rule the state, would run away. We do not mean run away from the field; for, truly, very few of those who now raise the cry for economy and disarming would be found there. We mean they would counsel, and, in fact, insist on submission. Many brave men would doubtless be found in the towns, and multitudes in the country, who would be eager at the posts of danger; but the great bulk of the wealthy and influential classes, at least in the great cities, would loudly call out for an accommodation on any terms. They would surrender the fleets, dismantle Portsmouth and Plymouth, cede Gibraltar and Malta —anything to stop the crisis. They would do so for the same reason that they now so earnestly counsel disbanding the troops and selling the ships of the line, and under the influence of a much more cogent necessity – in order to be able to continue without interruption the making of money. Peace, peace! would be the universal cry, at least among the rich in the towns, as it was in Paris in 1814. There would be no thought of imitating the burning of Moscow, or renewing the sacrifice of Numantia. The feeling among the vast majority of the manufacturing and mercantile classes would be – "What is the use of fighting and prolonging so terrible a crisis? Our workmen are starving, our harbours are blockaded, our trade is gone, we are evidently overmatched; let us on any terms get out of the contest, and sit quietly on our cotton bags, to make money by weaving cloth for our conquerors."

We have said enough, we think, to make every thoughtful and impartial mind contemplate with the most serious disquietude the prospect which is before us, under our present system of cheapening everything, and, as a necessary consequence, reducing the national armaments to a pitiable degree of weakness in the midst of general hostility, and the greatest possible increase of available forces on the part of all our neighbours, rivals, and enemies. But let us suppose that we are entirely wrong in all we have hitherto advanced – that there is not the slightest danger of an invasion or blockade from foreign powers, or that our home forces are so considerable as to render any such attempt on their part utterly hopeless. There are three other circumstances, the direct effects of our present Free Trade policy, any one of which is fully adequate in no distant period to destroy our independence, and from the combined operation of which nothing but national subjugation and ultimate ruin can be anticipated.

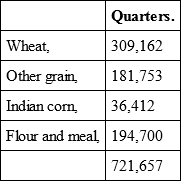

The first is the extraordinary and appalling increase which, since Free Trade was introduced, has taken place in the proportion of the daily food of our population which is furnished by foreign states. Before the great change in our policy began, the nation had been rendered, practically speaking, self-supporting. The importation of wheat, for the five years from 1830 to 1835, was only 398,000 quarters; and even during the five bad years in succession, from 1836 to 1841, the average importation was only 1,700,000 quarters. From 1830 to 1840, the average importation of wheat and flour was only 907,000 quarters.10 But since the great change of 1846, the state of matters has been so completely changed that it is now notorious that, in ordinary years, the importations cannot be expected to be ever less than 9,000,000 or 10,000,000 quarters of grain, about 5,000,000 quarters of which consists of wheat.11 The importation in the single month of July last, in the face of prices about 42s. the quarter, was no less than 1,700,000 quarters of all sorts of grain;12 and in the month ending November 5, with prices about 39s. 9d. the quarter of wheat, the importation was: —

– Price, 39s. 9d. quarter of wheat.

The average of prices for the last twelve weeks has been 39s. 9d. the quarter; but the importation goes on without the least diminution, and accordingly the Mark Lane Express of December 28, 1850, observes, —

"In the commencement of the year now about to terminate, an opinion was very prevalent that prices of grain (more especially those of wheat) had been somewhat unduly depressed; and it was then thought that, even with Free Trade, the value of the article would not for any lengthened period be kept down below the cost of production in this country. The experience of the last twelve months has, however, proved that this idea was erroneous; for, with a crop very much inferior to that of 1849, quotations have, on the whole, ruled lower, the average price for the kingdom for the year 1850 being only about 40s., whilst that for the preceding twelve months was 44s. 4d. per quarter. This fact is, we think, sufficient to convince all parties that, so long as the laws of import remain as they now stand, a higher range of prices than that we have had since our ports have been thrown open cannot be safely reckoned on. The experiment has now had two years' trial; the first was one in which a considerable failure of the potato crop took place in England and Ireland; and this season we have had a deficient harvest of almost all descriptions of grain over the whole of Great Britain. If, under these circumstances, foreign growers have found no difficulty in furnishing supplies so extensive as to keep down prices here at a point at which farmers have been unable to obtain a fair return for their industry and interest for the capital employed, we can hardly calculate on more remunerating rates during fair average seasons. Under certain combinations of circumstances prices may, perhaps, at times be somewhat higher; but viewing the matter on the broad principle, we feel satisfied that, with Free Trade, the producers of wheat will rarely receive equal to 5s. per bushel for their crop."

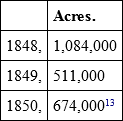

Accordingly, so notorious has this fact become, and so familiar have the public become with it, that it has become a common-place remark, which is making the round of all the newspapers without exciting any attention, that the food of 7,000,000 of our people has come to depend on supplies from foreign countries. In fact a much larger proportion than this, of the wheaten food of the country, comes from abroad; for the total wheat consumed in Great Britain and Ireland is under 15,000,000 quarters, and the importation of wheat is from 4,000,000 to 5,000,000 quarters, which is about a third. And of the corresponding decrease in our own production of grain, a decisive proof has been afforded by the decline since 1846 in wheat grown in Ireland, the only part of the empire where such returns are made, which has stood thus: —

Примечание 113

Now, assuming – as experience warrants us in doing – this state of matters to be permanent, and the growth of wheat in the British Islands to be progressively superseded by importations from abroad, how is the national independence to be maintained, when a fourth of our people have come to depend on foreign supplies for their daily food? Nearly all this grain, be it recollected, comes from two countries only – Russia, or Poland which it governs, and America. If these two powers are desirous of beating down the naval superiority, or ruining the commerce and manufactures of Great Britain, they need not fit out a ship of the line, or embark a battalion to effect their purpose; they have only to pass a Non-Intercourse Act, as they both did in 1811, and wheat will at once rise to 120s. the quarter in this country; and in three months we must haul down our colours, and submit to any terms they may choose to dictate.

In another respect our state of dependence is still greater, for we rest almost entirely on the supplies obtained from a single state. No one need be told that five-sixths, often nine-tenths, of the supply of cotton consumed in our manufactures come from America, and that seven or eight hundred thousand persons are directly or indirectly employed in the operations which take place upon it. Suppose America wishes to bully us, to make us abandon Canada or Jamaica for example, she has no need to go to war. She has only to stop the export of cotton for six months, and the whole of our manufacturing counties are starving or in rebellion; while a temporary cessation of profit is the only inconvenience they experience on the other side of the Atlantic. Can we call ourselves independent in such circumstances? We might have been independent: Jamaica, Demerara, and India, might have furnished cotton enough for all our wants. Why, then, do they not do so? The mania of cheapening everything has done it all. We have ruined the West Indies by emancipating the negroes, and then admitting foreign sugar all but on the same terms as our own, and therefore cotton cannot be raised to a profit in those rich islands – for continuous labour, of which the emancipated negroes are incapable, is indispensable to its production. In the East Indies, the cultivation of cotton has not been able to make any material progress, because the mania of Free Trade lets in American cotton, grown at half the expense, without protection. We have sold our independence, not like Esau, for a mess of pottage, but for a bale of cotton.

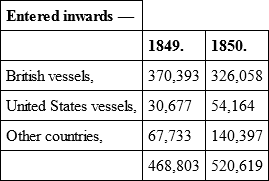

In the next place, the progressive and rapid decrease in our shipping, and increase of the foreign employed in carrying on our trade, since the Navigation Laws were repealed, is so great that from that quarter also the utmost danger to our independence may be anticipated. We need not remind our readers how often and earnestly we have predicted that this effect must take place; and we shall now proceed to show how completely, to the very letter, these prognostics have been verified: —

The shipping returns of the Board of Trade, for the month ending the 5th of November, present the following results: —

Tonnage for the month ending Nov. 5

– Times, Dec. 7, 1850.

The general results for the ten months, from January 1, 1850, when the repeal of the Navigation Laws took effect, to October 31, are as follows, and have been thus admirably stated by Mr Young: —

"In the year 1840, the total amount of tonnage entered inwards, in the foreign trade of the United Kingdom, was 4,105,207 tons, of which 2,307,367 were British, and 1,297,840 foreign. In 1845, the British tonnage had advanced to 3,669,853, and the foreign to 1,353,735, making an aggregate of 5,023,588 tons. In 1849, the British entries were 4,390,375, the foreign 1,680,894 – together 6,071,269 tons. Thus, in ten years, with a growing commerce, but under protection, British tonnage had progressively increased 1,583,008 tons, or 56-1/3 per cent.; and foreign 383,054 tons, or 29½ per cent. At this point, protection was withdrawn. Free navigation has now been ten months in operation, and the following is the result: —