полная версия

полная версияDwarf Fruit Trees

III

PROPAGATION

The propagation of dwarf fruit trees is in some senses a more critical and interesting problem than the propagation of ordinary nursery stock. The successful production of a dwarf fruit tree depends primarily on its propagation. The selection of stocks for dwarfing purposes is necessarily a complicated matter. Under the terms of the problem it is impossible that the stock and the cion which are wedded together should be very closely related. The stock must be distinctly different and pronouncedly dwarfer in his habit of growth.

It is not always an easy matter to find a stock which is thus distinctly different from the tree which it is desired to grow and which will at the same time form with it a vigorous and long lived union. It is necessary further that the propagation can be carried on with ease and with a fair degree of success in commercial nurseries. If difficult methods of grafting are required, or if only a small stand of nursery trees can be secured, the undertaking becomes too expensive from the nurseryman's point of view.

The methods of propagating dwarf trees are for the most part the same as those used in reproducing the same kinds of fruit on standard stocks. As a matter of fact nearly all dwarf trees are propagated by budding. Apples, pears, and plums can be readily grafted, but budding is simpler, speedier, and usually the cheaper process in the nursery. In the upper Mississippi Valley, where plums are somewhat extensively worked on Americana plum roots, grafting is rather common. The side graft and the whip graft are the forms most used.

The theory of the production of a dwarf fruit tree by the restraining of its growth has already been mentioned in another chapter. The dwarf stock simply supplies less food than is required for the normal growth of the variety under propagation, and the tree is, in a sense, starved or stunted into its dwarf stature.

As the selection of proper stocks—the adaptation of stock to cion—is one of the fundamental problems in dwarf fruit growing, we may now address ourselves to that. We will take up the different classes of fruit in order.

THE APPLE

Everyone who has observed the wild or native apples which grow in New England pastures must frequently have noticed certain dwarf and slow-growing specimens. It it not difficult to find such which do not reach a height of five feet in ten years of unobstructed growth. If the cions of ordinary varieties of apples like Greening and Winesap should be grafted upon these stocks, the result would be a dwarf Greening or Winesap. If these dwarf wild apples could be produced with certainty and at a low price, they would furnish a source of supply for dwarf apple stocks.

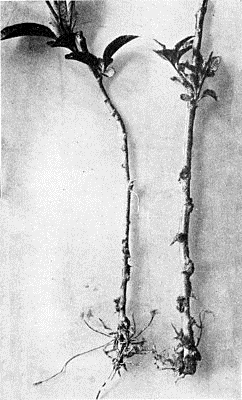

The Paradise apple so-called (Fig. 7) is simply one of these dwarf varieties which can be reproduced freely and cheaply. This reproduction is secured nearly always by means of mound layerage. As the variety does not come true to seed, any more than such varieties as King or Hubbardston do, some such method of propagation is necessary. This Paradise apple is naturally inclined to stool out somewhat from the roots. This habit is encouraged by cutting the plants back to the ground. When the young shoots are thrown up they are banked up with a hoe or by plowing furrows up against the rows of plants. The young shoots then form roots at the base and these rooted shoots or layers are removed when one year old. They are then planted in nursery rows in the spring, where they are usually budded the following July or August.

These Paradise stocks are largely grown in France. Practically all the supply comes from that country. The nurserymen who grow dwarf apple trees in America import their stocks from France during the winter, plant them in nursery rows early in the spring, bud the stocks the following July or August, and have the dwarf apple trees for sale the second year following.

This Paradise is the dwarfest stock known for apples. Its effect on nearly all varieties is very marked, causing them to form very small trees and to bear very early. Some of the more vigorous varieties, like Northern Spy for instance, do not submit kindly to such treatment. For this, or possibly for more recondite reasons, a few varieties do not succeed well on Paradise roots. The writer would be glad to give a list of such varieties which are not adapted to the Paradise stock, but confesses he is unable to do so.

FIG. 7—PARADISE APPLE STOCKS IN EARLY SPRING

The Doucin stock is simply another variety of dwarf apple. It is more vigorous and larger growing than the Paradise, and, therefore, produces a tree, when ordinary varieties are grafted upon it, about midway in size between the ordinary standard apple and the same variety growing upon Paradise.

This Doucin is sometimes called the English or Broad-Leaved Paradise, but this name is misleading. It will be well to remember this in buying stocks or in buying trees in England. Dwarf apples are largely propagated in England, but the trees which are said to be on Paradise roots are often on Doucin. This confusion comes about from the Englishman's habit of calling Doucin the Broad-Leaved Paradise.

The Doucin is perhaps better for the free-growing bush form trees, especially where excessive dwarfing is not needed. For orchard planting in the United States this Doucin stock would be likely to suit many growers better than Paradise. For trees which are to be kept within very narrow bounds, or those which are to be trained in particular forms, the Paradise stock is better. For all sorts of cordon apple trees, the Paradise is essential.

THE PEAR

Dwarf pears are always propagated on quince roots. Any kind of a quince may be used as a stock for pears, but the one commonly employed by nurserymen is the Angers quince, named after Angers, France, from which place the supply largely comes. Almost all the quince stocks used by nurserymen in America are imported from France. As in dealing with apple stocks, the importation is made during the winter, the stocks are planted in nursery rows in the early spring, and are usually budded in July or August of the same year.

A few varieties of pears do not make good unions with the quince. In some cases this antipathy is overcome by the expedient of double-working. The quince root is first budded with some variety which unites well with it. After this pear cion has grown one year, the refractory variety is budded upon this pear shoot. The complete tree, when it leaves the nursery, consists of three pieces,—a quince root below, a pear top above, and a short section of only one or two inches in length of some other variety of pear which simply holds together the two essential parts of the tree.

This practise of double-working is sometimes undertaken with other kinds of fruit for special purposes. There are no other cases, however, in which it becomes a generally recognized commercial practise.

THE PEACH

The peach is dwarfed by budding it upon almost any kind of a plum root, especially upon the smaller growing species of plums. The stock most used is the ordinary Myrobalan plum. This is simply because the Myrobalan stock is commoner and cheaper. The St. Julien plum probably furnishes a better dwarfing stock for peaches, but it is more expensive and harder to work.

The Americana plum, now somewhat largely grown for stocks in the States of the upper Mississippi valley, furnishes a good dwarfing stock for the peach. According to the writer's experience the Americana stock gives better results with peaches than either Myrobalan or St. Julien. It should be observed that this stock requires budding rather early in the season.

The dwarf sand cherry, which is further discussed below under plums, also makes a good stock for peaches. As this stock is very dwarf, it produces the smallest possible peach tree. The peach cion rapidly overgrows the stock and the tree can hardly be expected to be long lived. The growth is very vigorous and satisfactory during early years, however. I have not had an opportunity to determine how long peaches will live and thrive on this stock.

Nectarines can be grown in dwarf form in exactly the same manner employed for peaches.

THE PLUM

In all the old books it is said that dwarf plum trees are secured by working on Myrobalan stocks. This statement is hardly true according to our present standards, and is certainly far from satisfactory. This rule came into vogue at the time when only large growing Domestica plums were propagated in this country and the stocks used were mostly either "horse plums" or Myrobalan. The Myrobalan stock does give a somewhat smaller tree than the old fashioned horse plums; but this Myrobalan stock has been for many years the one principally used for propagating all kinds of plums in America. It has come to be looked upon as a standard rather than a dwarf stock. When we think of dwarf trees, therefore, we expect to see something smaller than what will grow under ordinary circumstances on a Myrobalan root.

The Americana plum, already mentioned, is a first-rate stock in nearly all respects except that it can not be bought so cheaply as the Myrobalan. It is now grown to a considerable extent by nurserymen in Minnesota, Iowa and the neighboring States. If grafted, or budded early, all varieties of plums take well upon it. The trees on Americana roots make a good growth in the nursery and are easily transplanted. The tree produced on this stock is only moderately dwarf. Still this dwarfing effect is always well marked, this result being shown by the overgrowing of the cion. The top thus appears to outgrow the root, and such trees are apt to blow over during wind storms. Suitable precautions should be taken to guard against damage of this sort.

Prof. A. T. Erwin of Iowa writes on this subject as follows:

"Regarding the Americana as a plum stock, I would state that we are using it by the thousands out here; in fact, have about quit using anything else. As a stock for the European and Japanese sorts, it does dwarf them, and the cion tends to outgrow the stock at the point of union, causing an enlargement. The union is also not very congenial, and they frequently break off on account of high winds. However, in my experience and observation, this is not the case when the Americana is used as a stock for Americana varieties. It does not dwarf the trees seriously and the union is splendid. It is by all odds the best stock we have for plums, and since we do not grow anything but Americana varieties, it works first rate. It does tend to sprout some, though there is little trouble in this regard after the trees come into bearing."

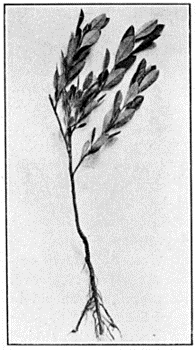

FIG. 8

THE WESTERN SAND CHERRY

Prunus pumila besseyi

The sand cherry seems to be the dwarfing stock par excellence for the plum. This sand cherry is a heterogeneous species, or as some botanists think, is three species, ranging throughout the Northern States from Maine to Colorado. The narrow leaf upright form growing about five feet tall, known as Prunus pumila, is found along the Atlantic coast. The broad leafed dwarfer form known as Prunus pumila besseyi or P. besseyi, is found in the Western States. Another rarer form of more irregular growth known as Prunus pumila cuneata, or as P. cuneata, is found in the North Central States.

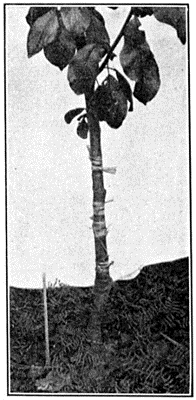

FIG. 9—UPRIGHT CORDON PLUM

With buds set into the naked trunk

All of these different forms may be used for propagating plums or peaches. The western form (P. besseyi) (Fig. 8) is in some respects the best, producing the dwarfest and apparently the best trees. In our experience, however, nearly all varieties of plums and peaches give a better stand of trees when budded on P. pumila. Prunus cuneata is inferior to the others.

The eastern form, P. pumila, has another advantage from the standpoint of the nurseryman in that it is more easily propagated from cuttings. For the most part the western sand cherry is propagated from seed. Both forms can be propagated from layers.

NURSERY MANAGEMENT

Dwarf trees are managed in the nursery very much the same as standards of the same varieties. There are no special points to be observed except in the formation of the tops. Western New York nurserymen, who now grow the principal supply of dwarf apple and pear trees, have the custom of forming their nursery stock with high heads. That is, the heads are formed at a height of eighteen inches to three feet from the ground. In this matter the pattern is taken after the usual style of standard trees. This is quite wrong. Of course, some planters might like to have dwarf trees with trunks two or three feet tall, but the best form has a much shorter stem. At any rate the buyer of dwarf trees ought to be at liberty to form the head within three or four inches of the ground if he so desires. This becomes very difficult if the tree is once pruned up to a height of two or three feet.

In order that the planter may reach his own ideal perfectly in this matter, it is sometimes necessary to buy one year old trees, what the English nurserymen call maidens. This, of course, enables the tree planter to form the head wherever he desires.

IV

PRUNING DWARF FRUIT TREES

The pruning of dwarf fruit trees is a matter of the greatest consequence, for on proper pruning depend both the form and the productivity of the trees. Some of the details of management will be explained in the succeeding chapters, dealing with the particular kinds of fruits, but a few general statements should be set down here.

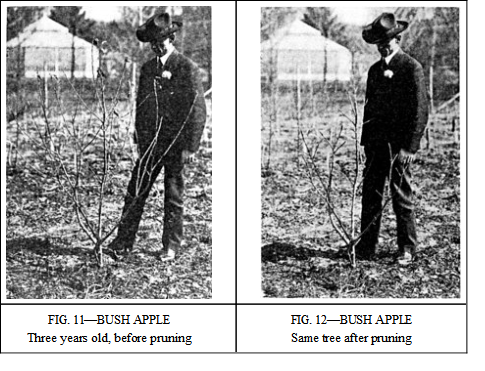

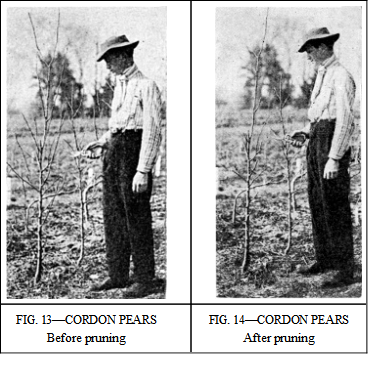

1. The trees are severely headed in. This applies more particularly to bush and pyramid forms. By the term "heading in" we refer to the shortening of the leaders. Such shortening is usually given at the spring pruning, while the trees are dormant. The leaders may be headed in at times, however, during the latter part of the growing season, in July. Such stopping of growing leaders will be practised more often on young trees just coming into bearing than on old trees. (Fig. 10). Constant heading back of some sort, however, is required in nearly all cases, if the tree is to be retained in its dwarf form. The mistake has often been made of thinking that a tree propagated on a dwarf root would take care of itself.

2. Summer pruning is essential. In most American orchard practise one annual pruning (sometimes one pruning every five years!) is considered sufficient, and systematic summer pruning is seldom or never given. Now summer pruning tends much more to repress the growth of a tree than winter pruning does. In fact, heavy winter pruning leads rather to increased vegetative vigor. Aside from any special system of pruning, therefore, this rule is to be remembered, that summer pruning is desirable, on general principles, for dwarf fruit trees.

FIG. 10—BUSH APPLE, THREE YEARS OLD

Showing strong leaders formed during the summer

3. Side shoots usually need pinching during the growing season. Leaders are more frequently allowed to grow unchecked throughout the season, or are stopped only late in their period of development. In the pomaceous fruits, which form distinct fruit spurs, the checking of these side shoots helps toward the production of fruit buds. As long as every bud is allowed to push out into a strong shoot no fruit spurs can become established. Thus the summer pinching of the side shoots on apples and pears has the purpose of encouraging the formation of fruit spurs. On peach and plum trees equally distinct fruit spurs do not form; but if the side shoots are allowed to push forth unrestricted they are apt to choke one another. There will be too many of them, they will not get light enough, their growth will be weak and sappy, and they will not form fruit buds. Good fruit buds on a peach tree, for example, form on strong, clean, healthy shoots of this year's growth for next year's crop of fruit. It is seen, therefore, that in nearly all sorts of dwarf fruit trees the summer pruning is especially directed to the suppression or regulation of the growth of side shoots.

This part of the treatment becomes of prime importance in dealing with cordons and espaliers.

4. The control of the fruit spurs or of the side shoots here contemplated requires that the trees be gone over more than once during the growing season. In fact, four successive examinations of the tree are usually required. Old trees can sometimes be managed with two or three, but young ones, on the other hand, will sometimes require six or more. Of course, there are usually only a few shoots that need attention at each succeeding visit, and the work can be very rapidly performed. The first pruning, or pinching, falls about three weeks after the trees have started into growth. The next one comes ten days later, the next one ten days later again, and the fourth pruning two weeks after the third. From this time onward the intervals lengthen. These specifications, of course, are only approximate and suggestive. Some judgment is required to select just the proper moment for pinching back a shoot and even more to select the time for a general summer pruning. Those trees which enjoy the sympathetic presence of the gardener every day are sure to fare best. The bulk of this pruning can be done with the thumb nail and forefinger, but I find a light pair of pruning scissors pleasanter to work with.

5. Root pruning is sometimes advisable. Since the whole program is arranged to check the growth of the dwarf tree, root pruning would naturally fit well with the other practises recommended. Root pruning checks the growth of a tree about as positively as any treatment that can be devised. When dwarf pear or apple trees seem to be making too much wood growth and not enough fruit, they can be taken up, as for transplanting, during the dormant season and set right back into place. This digging up and replanting is always accompanied by some cutting of roots. The whole root system is disturbed and has to re-establish itself before the top vegetates very strongly once more. Such root pruning ought to be done late in the fall. It is a special practice, suited to refractory cases, and the gardener is not recommended to indulge in it too freely.

6. A certain equilibrium between vegetative growth and fruit bearing should be established at the earliest possible moment, and should be maintained thereafter. Of course, some such equilibrium is sought in the management of a standard tree; but it is secured earlier in the life of the dwarf tree and should be much more accurately maintained. The tree must make a certain amount of growth each year, but this must be only enough to keep it in good health, and to furnish foliage enough to mature the fruit. Beyond this wood growth the tree should bear a certain amount of fruit every year, for annual bearing is not only an ideal but a rule in the management of dwarf trees. This equilibrium once established must be maintained not by haphazard pruning, but by some suitable system. If there is the proper balance between summer pruning and winter pruning, combined with proper control of cultivation and fertilization, then the balance between vegetation and fruitage can be kept up. It is a delicate business, like courting two girls at once, but it can be carried out successfully.

7. The training of trees into mathematical forms is largely a mechanical process. For the most part the trees are shaped while they are growing. The young shoots are twisted and bent to the desired positions, and are tied into place until the stems become hardened. There are many clever little tricks for expediting this sort of work and for making the results more sure, but a rehearsal of them here would be tedious. The most important rule to remember is that constant attention must be given the shoots while they are growing. Mistakes are corrected with difficulty after an undesirable form has been allowed to harden.

V

SPECIAL FORMS FOR TRAINED TREES

We have already explained the connection between dwarf trees and the practise of training them in special forms. It is true that this practise looks childish to American eyes. It seems to be only a kind of play, and a rather juvenile sport at that. Nevertheless we should understand that in some parts of the world it is a real and profitable commercial undertaking. We should consider also that in other places, where fruit of very high quality is better appreciated, perhaps, than it is in America, the extra trouble is thought to be worth while for the superior quality which it gives the fruit. As this matter is coming to be of more importance in America also, and as the interest in amateur fruit growing is enormously increasing, we may fairly begin to talk about these methods.

The formation of trees into bushes and pyramids, by means of systematic pruning according to a definite plan, as explained in the succeeding chapters, while apparently simpler and more reasonable to our American eyes, it is still a method of training the tree. The fruiting branches are placed at definite points and the fruit spurs are encouraged to grow in regular succession. It is not a very great step from this to a distribution of the branches into a more precise form.

The different forms which are used most commonly are named and classified in the following outline:

A.—Forms of three dimensions:

a. Vase or bush

b. Pyramid

c. Winged pyramid, etc.

B.—Forms of two dimensions:

a. Various espaliers

b. Palmette-Verrier

c. Fans or Fan-espaliers

d. U-form and double U-form

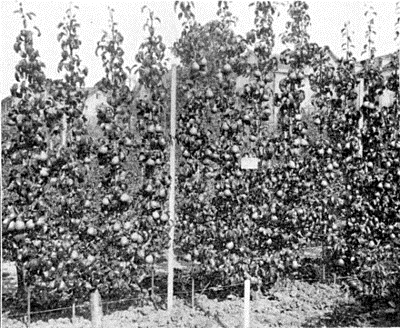

C.—Trained to a single stem:

a. Upright cordon

b. Oblique cordon

c. Horizontal cordon

(with one arm)

(with two arms)

d. Serpentine cordon, etc.

Among the forms of three dimensions none is of much practical importance besides the pyramid and bush or vase form. These are sufficiently explained in the chapters on pears and apples. Here we need only to define them. The pyramid tree is one which has a straight central stem with branches radiating therefrom. It is especially adapted to upright growing varieties of pears. The bush or vase form has several main arms or branches, all standing out from approximately the same point and growing upward at a more or less acute angle, thus forming roughly a vase. The secondary branches put out from these, bearing fruiting wood, as the gardener may order.

FIG. 15—PEARS IN DOUBLE U-FORM

From Loebner's "Zwergobstbäume"

The flying pyramid or winged pyramid, described in all European books, is considerably different from the ordinary pyramid and is more precise in its design. Usually six arms are brought out at the base of the tree. These are grown in a direction approximately horizontal until they reach a convenient length,—say two to three feet. They are then suddenly bent upward and inward and are conducted along wires set for this purpose until they meet in a common point with the main stem of the tree some four to eight feet above where the branches put out. There is thus formed a precise mathematical pyramid. Along these main arms fruiting spurs are allowed to grow, but no branches are expected to develop.

Sometimes the flying pyramid is made more elaborate by bending the arms into a spiral form. Other more or less complex modifications are practised to some extent. All of them are to be regarded merely as curiosities and as of no practical value.