полная версия

полная версияDwarf Fruit Trees

F. A. Waugh

Dwarf Fruit Trees / Their propagation, pruning, and general management, adapted to the United States and Canada

PREFACE

The commercial interests have so continuously and completely held the horticultural stage in America during the last two decades that it has been impossible for amateur horticulture to get in a word edgewise. Any public speaker or writer has had to talk about several acres at a time or he would not be listened to. He has been obliged to insist that his scheme would pay on a commercial scale before anyone would hear, much less consider, what he had to tell.

But now a change is coming. Different conditions are already upon us. A thousand signs indicate the new era. With hundreds—yes thousands—of men and women now horticulture is an avocation, a pastime. They grow trees largely for the pleasure of it; and their gardens are built amidst surroundings which would make commercial pomology laugh at itself.

And so I undertake to offer the first American fruit book in a quarter century which can boldly declare its independence of the professional element in fruit growing. I am confident that dwarf fruit trees have some commercial possibilities, but they are of far greater importance to the small householder, the owner of the private "estate," the village dweller, the suburbanite and the commuter.

In other words, while I hope that all good people will be interested in dwarf fruit trees and that some of them will share the enthusiasm of which this book is begotten, I do not want anyone to think that I have issued any guaranty, expressed or implied, that dwarf trees will open a paying commercial enterprise. Because the argument that a thing pays has been so long the only recommendation offered for any horticultural scheme, many persons have formed the habit of assuming that every sort of praise stands on this one foundation.

F. A. Waugh.

Massachusetts Agricultural College, 1906.

I

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

A dwarf fruit tree is simply one which does not reach full size. It is not so large as it might be expected to be. It is smaller than a normal tree of the same variety and age.

There are indeed some trees which are normally dwarf, so to speak. They never reach a considerable size. They are smaller than other better known and related species. For example, the species Prunus pumila besseyi is sometimes called the dwarf sand cherry, simply because it is always notably smaller than related species. The Paradise apple is spoken of as a dwarf because it never attains the stature which other apples attain.

But in the technical sense, as the term is used by nurserymen and pomologists, a dwarf tree is one which is made, by some artificial means, to grow smaller than normal trees of the same variety.

These artificial means used for making dwarf trees are chiefly three: (1) propagation on dwarfing stocks, (2) repressive pruning, and (3) training to some prescribed form.

DWARFING STOCKS

The most common and important means of securing dwarf trees is that of propagating them on dwarfing stocks. These are simply such roots as make a slower and weaker growth than the trees from which cions are taken. This will be understood better from a concrete example. The quince tree normally grows slower than the pear, and usually reaches about half the size at maturity. Now pear cions will unite readily with quince roots and will grow in good health for many years. But when a pear tree is thus dependent for daily food on a quince root it fares like Oliver Twist. It never gets enough. It is always starved. It makes considerably less annual growth, and never (or at least seldom) reaches the size which it might have reached if it had been growing on a pear root.

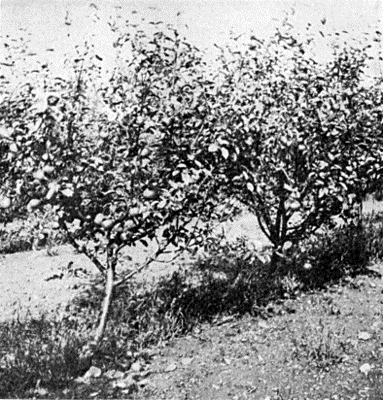

This is, somewhat roughly stated, the whole theory of dwarfing fruit trees by grafting them on slow-growing stocks. The tree top is always under-nourished and thus restrained in its ambitious growth of branches, as seen in Fig. 1.

While the tree is made thus smaller by being grafted on a restraining root, it is not affected in its other characteristics. At least theoretically it is not. It still bears the same kind of fruit and foliage. Bartlett pear trees budded on quince roots yield fruit true to name. The pears are still Bartletts, and can not be told from those grown on an ordinary tree. Sometimes the fruit from dwarf trees seems to be better colored or better flavored than that from standard trees; but such differences are very delicate and usually receive slight thought.

FIG. 1—DWARF APPLE TREES IN WESTERN NEW YORK

Dwarf fruit trees have not been very largely grown in America, but have been much more widely used in Europe. This statement holds good either for commercial plantations or for private fruit gardens. They are coming into more common use in this country because, in both market orchards and amateur gardens, our pomology is coming to be somewhat more like that of Europe. Our conditions are approaching those of the Old World, even though they will always be very different from those of Europe in horticultural matters.

Dwarf fruit trees are particularly valuable in small gardens; and small gardens are becoming constantly more popular among our urban, and especially our suburban, population. This matter is discussed more fully in another chapter. Fruit of finer quality can be grown on dwarf trees, as a general rule, than can usually be grown on standard trees. Every year there are more people in America who are willing to take any necessary pains to secure fruit of extra quality. This remark applies particularly to amateur fruit growers and to owners of private estates who grow fruit for their own tables, but it is no less true of a certain class of fruit buyers, especially in the richer cities. Although $3 a barrel is still a high price for ordinary good apples, sales of fancy apples at $3 a dozen fruits are by no means infrequent in the city markets every winter.

FIG. 2—TRAINED CORDON APPLE TREES

From Loebner's "Zwergobstbäume"

In this respect also we are approaching European conditions. In the markets of the continental capitals in particular fancy fruits are frequently sold at prices which seem almost incredible to an American. Single apples sometimes bring 50 cents to a dollar, and peaches an equal price. Just recently a story has been going the rounds of the newspapers that the caterer for the Czar's table sometimes pays as high as $15 apiece for peaches for the royal table. Hereupon a solemn American editor remarked that if the whole royal family should live upon nothing but peaches it would still be cheaper than carrying on the Japanese war.

Now if there is anywhere within reach a market for apples or peaches at $3 a dozen specimens—and there unquestionably is—then it will pay to grow fancy fruits with special care to meet this demand. This kind of fruit can be grown better upon dwarf trees than upon standards in many cases, if not in most. At least such is the conviction of the present writer. Moreover this has been the experience in the old country.

With such facts in view there seems to be a possible future for dwarf fruit trees, even for commercial purposes. Their present utility in amateur gardens and on wealthy private estates can not be questioned. These various amateur and commercial adaptations of dwarf trees will have to be more carefully analyzed and discussed in a future chapter, and the subject may therefore be dropped for the present.

FIG. 3—BISMARCK APPLE, FIRST YEAR PLANTED

22 inches high; bearing 4 fruits

II

ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES

It is a good prejudice which expects every man who writes anything to be enthusiastic over his subject. Such enthusiasm doubtless leads a writer many times to over-state his case, and to claim more than the calm judgment of the multitude will ratify. And on the other hand, readers usually tacitly discount the statements of any man who writes about any matter in which he is plainly interested. The present writer knows that he is also under the ban, and that the reader firmly expects him to claim more for dwarf fruit trees than their merits will fairly warrant. This expectation the writer hopes to disappoint. It will be enough to set down here the obvious advantages and disadvantages which the horticulturist will meet in handling dwarf fruit trees. These statements are mostly of matters of common experience and they need no coloring to make them serve their present purpose.

We may fairly set down the following good points standing more or less generally to the credit of dwarf fruit trees:

1. Early bearing.—This is a sufficiently obvious advantage. The Alexander apple will bear the second year after planting when grown as a dwarf, while it requires six to ten years to come into bearing as a standard. This habit of early bearing proves valuable in many ways. It encourages men to plant trees. The disinclination of old men to plant trees rests upon the slenderness of the chance that they will ever gather of the fruit. But a man may plant dwarf trees whenever his expectation of life is two years or more. Such trees would serve octogenarians, consumptives and those sentenced to be hanged for murder.

FIG. 4—PEAR TREE, TRAINED AS AN ESPALIER

Early bearing—to return to the subject—makes dwarf trees valuable to that large and unfortunately growing class of citizens who rent the premises where they live. They do not expect to stay more than five or six years in any one place. In that length of time ordinary trees would not begin to yield any fruit. But with dwarf trees there is excellent probability of seeing something ripen. Then again early bearing is a great advantage when one is testing new or old varieties. It is a great advantage when a commercial orchard is designed and when dwarf trees are used for fillers as explained below.

2. Small size.—The very smallness of the dwarf trees has many advantages in it. The trees are easier to reach and to care for. They are easier to prune and to spray. This facility in spraying is what has chiefly recommended smaller fruit trees to commercial fruit growers in recent years. Particularly in those places where the San José scale is a perennial problem a very large tree becomes an impossibility, and the smaller the trees can be the better it suits.

The small size of dwarf trees permits the planting of larger numbers on a given area. This is specially worth while to the amateur who has a small garden where only three or four standard trees could grow, but where he can comfortably handle forty or fifty dwarfs. Yet it is also worth the consideration of the commercial fruit grower who is trying to earn a profit on expensive land. If he can increase the number of bearing trees on each acre, especially during the early years of establishing his orchard, it almost certainly means increased income.

FIG. 5—BUSH APPLE TREE, THREE YEARS PLANTED

3. High quality.—It is not perfectly certain that every kind of fruit can be produced in higher quality on dwarf trees than on standards, but such is the general rule. This is notably true of certain pears, as Buerré Giffard and Doyenne du Comice, and it is generally the case with all apples that can be successfully grown on Paradise roots. One can secure size, color, flavor and finish on an Alexander or a Ribston Pippin, for example, which can never be secured on a standard tree. One who has not seen this thing done will hardly understand it; those who have will not need more argument. Such plums as we have fruited on dwarf trees have shown similar improvement in quality, being always distinctly superior to the same varieties grown on standard trees. The significance of these facts will appear at once to any one familiar with the course of the fruit markets in America. There are greater rewards awaiting the fruit grower who can produce fruit of superior quality than the one who succeeds merely in increasing the quantity of his output.

SPECIAL USES FOR DWARF TREES

These various items of advantage recommend dwarf fruit trees for several specific purposes, some of which are worth pointing out in detail.

1. For suburban places.—A large and increasing percentage of our population now lives the suburban life—in that zone where city and country meet. They have small tracts of land, which, however, they too often lease instead of owning. On these they do more or less gardening,—usually more, in proportion to the size of their holdings. For them dwarf fruit trees are a precious boon. It is possible to plant three hundred to five hundred dwarf fruit trees on a quarter of an acre, where less than a dozen standard trees would flourish. This gives the opportunity to experiment with all sorts and varieties of fruits, a privilege very dear to the heart of the commuter. The dwarf fruit trees also work more readily into a scheme of more or less ornamental gardening, where fruits are combined with vegetables and flowers. Especially if some sort of formal gardening is attempted, the cordons, espaliers and pyramids exactly suit the demands. Then the fact, already mentioned, that the dwarf trees come into bearing much sooner, is a consideration of the highest value to the suburban gardener. He fully expects to move from one home to another at least once in ten years, if not once in five. With the best of intentions and the most favorable of opportunities he can hardly expect to settle down anywhere for life. The suburbs themselves change too rapidly for that; and the place which today is away off in the country may be all covered with factories five years from now. It is terribly discouraging, under such circumstances, to plant a tree knowing that ten years must pass before any considerable fruitage can be expected from it. It is altogether another feeling with which one plants a tree which promises fruit within two or three years.

So that, whatever the drawbacks to the planting of dwarfs, they are the salvation of the suburban garden. For such circumstances they can be freely recommended, without exception or reservation.

2. For orchard fillers.—As commercial orcharding becomes more refined, under the stress of modern competition, and as good orchard land increases in value, up to one hundred, two hundred, or even three hundred dollars an acre, new methods must be adopted with a view to increasing the returns. This opportunity looms especially large for the first few years after the establishment of the commercial orchard, more particularly the apple orchard. When standard trees are planted thirty-five to the acre, which is now the usual practice, the land is not more than one-fourth occupied for the first five years, and not more than half occupied for the first ten years. Indeed it is full twenty years from the time of planting before the thirty-five apple trees will use the whole acre. And since a good farmer can not afford to let expensive land lie idle he has before him a very pretty problem to determine how the space between the standard trees shall be utilized during the early years of the orchard's growth.

Several different methods are in vogue for the solution of this problem; but probably the best one is that system which supplies fillers or temporary trees between the standard or permanent ones. In an orchard of standard apple trees these fillers may very properly be dwarf apple trees; or between standard pears dwarf pears may be planted. If there are thirty-five standard apple trees to an acre, and if a dwarf tree is placed half way between each two standards in every direction, including the diagonal direction, this will make one hundred and five dwarf trees, or one hundred and forty trees in all, instead of the thirty-five trees with which the acre of apple orchard land is more commonly furnished. The dwarf apple trees will be bearing good crops at the end of five years at most; and they can be kept on the land for five years longer at the least, before they will begin to crowd the permanent standards. During these five years, if the orchard has a paying management at all, they will easily pay all the expenses of the enterprise, and should leave a substantial balance of profit.

As this system of filling, or interplanting, commercial orchards is becoming more and more common, the suitability of dwarf trees, for this purpose, becomes more generally evident.

3. For school gardens.—Thus far school gardens in America have been mostly temporary and experimental affairs. But we are already satisfied that they have come to stay, and that gardening in some form will be a permanent feature of the curriculum in many of our best schools. As soon as a school garden becomes a permanent institution, with ground of its own to be held in use year after year, the dependence on annual crops will give way to the use of various perennial plants, shrubs and trees.

And among these dwarf fruit trees will naturally be one of the first introductions. Their small size adapts them to the school premises, their habit of early bearing again serves to recommend them most strikingly, and the special opportunity which they offer to pupils to observe details of pruning and other items of tree management, make them almost a first necessity in the permanent school garden.

4. For covering walls and fences.—There are many places about every farm, suburban establishment, or even about many city homes, where back walls and fences could be put out of sight very agreeably by almost any sort of foliage. Various ornamental climbers and creepers are in vogue for this service; but a certain number of such unattractive walls and fences could be treated quite as acceptably, from the esthetic point of view, with trained fruit trees, and the result would be more satisfactory in some other ways. Apples or pears trained as cordons or espaliers, or peaches, nectarines, or cherries in fan forms, will thrive on almost any brick or wooden wall, except those with a northern front. It is necessary only to supply a proper soil, to plant sound trees of proper sorts, and to give them the prescribed care. The result is not only a thing of beauty but one of practical utility as well.

There are many places where the owner of a city or suburban lot can secure the fun and the substantial benefits belonging to the fruit grower on land that would be otherwise wasted, if he will only build a woven wire fence on the property line between him and his not-too-agreeable neighbor, using this fence as a support for a row of cordon plums, pears or apples. If he has time and inclination to do a little more work with the trees he can better plant U-form peaches, nectarines or apricots, or he can grow plums in U-form, or he can have fan-form cherry trees, or apples or pears in Verrier-palmettes. One of the most interesting and productive lots in the author's dwarf fruit garden is a row of plum trees on such a woven wire trellis. The trees in this row stand two feet apart, and form a perfect screen. (Fig. 6.) The majority of the trees which were necessarily taken for planting this row were not propagated on suitable stocks, and many varieties were introduced for experimental purposes which were obviously unadapted to this mode of training, but nevertheless the net result has been highly satisfactory.

FIG. 6—PLUMS AS UPRIGHT CORDONS, SET TWO FEET APART

In a very similar manner apple, pear or plum trees may be trained so as to form an arched arbor way. In this kind of make-up they present a most agreeable novelty. An example of this kind of training is shown in the illustration, page 5. For this purpose cordon trees are usually best; though peach or apricot trees in U-form or double U-form will answer very well. Even apple trees or pears formed as palmettes-Verrier can be carried up over an arched trellis.

Mr. Geo. Bunyard in "The Fruit Garden" tells of carrying apple trees up over the slate roof of an outbuilding, with marked success. The fruit-bearing portion of the trees, lying there on the slate roof beautifully exposed to the sun above, and assisted by the heat absorbed and radiated by the slate, yielded large crops of apples of very superior quality.

SOME DISADVANTAGES

There are, of course, some disadvantages in growing dwarf fruit trees, and these should be examined with as much care as the advantages. The more important ones are as follows:

1. Greater expense.—The trees are somewhat harder to propagate, and therefore cost more. There is no general demand for them in America, so that they are carried by only a few nurseries and are not looked upon as staple goods even with those dealers; and on this account the price is necessarily increased. Thus each tree costs more than a similar tree of the same age and variety propagated in the usual way. But the greatest increase of expense comes from the fact that many more trees are required to plant the same area. There is often an advantage, as already argued, in planting more trees to the acre, but it costs something to gain this advantage. An acre of ground can be planted with thirty-five standard apple trees set thirty-five feet apart each way, and these trees will cost, roughly estimating retail prices at $12 a hundred, $4.20. To plant an acre to dwarf apple trees, setting them six feet apart each way, which is about as thick as these trees should ever be planted, will require 1,210 trees. Estimating the retail price roughly at $15 a hundred this would make the first cost $181.50—a considerably greater initial investment in the orchard.

2. The trees are shorter lived.—This statement is true for certain kinds of dwarf trees, but not for others. Certain varieties of pears, for example, which do not unite well with the quince root, naturally make short lived trees. On the other hand other varieties of pears appear to live as long and thrive fully as well on quince roots as on pear roots. There is a common belief, especially in England, that apples worked on French paradise roots are apt to be short-lived. The nurserymen who hold this belief contend, however, that the so-called English Paradise, more properly called Doucin, supplies a stock on which apples will live to as great an age as on any other stock whatever. There is some evidence to show that vigorous varieties of plums worked on Americana roots or on dwarf sand cherry are shorter lived than the same varieties on freer growing stocks. In many cases, however, dwarf trees live as long as standards; and in almost all cases they live long enough.

3. They require more care.—This objection stands particularly against the dwarf trees trained in special and intricate forms. Such trees undoubtedly do require more careful attention, more frequent going-over, and more hand work in the course of the year. It is probably not true that apples, pears, plums or peaches in bush or pyramid forms require any more labor or attention than standard trees to secure equally good results. On the other hand it must not be forgotten, as has already been pointed out, that whatever care may be required is much more easily given the dwarf trees than the standards.

4. They are not a commercial success.—This statement, too, though undoubtedly having some truth in it, can not stand without qualification. It is certainly true that no one could grow ordinary varieties of apples, like Baldwin or Ben Davis for instance, on dwarf trees in competition with men who are growing the same varieties on standards. It is probably true that fancy varieties of apples can be grown with profit on dwarf trees, but even this can not be strongly urged. So far as apples are concerned the chief value of dwarf trees for modern commercial enterprises in America will come through their use as fillers between rows of standard trees. In the case of pears the situation is somewhat more favorable to dwarf trees. There are a number of orchards in this country where pears have been successfully grown for market, these many years, on dwarf trees. The famous and everywhere planted Bartlett succeeds admirably on the quince stock wherever the soil is suited to it. No successful commercial orchards of dwarf peaches or plums can be cited in this country, individual trees of these kinds even being extremely rare; yet there is good reason to suppose that under favorable conditions dwarf peaches and plums may have some commercial value. Such value may be more in the way of supplementing standard trees than in superseding them, but it is still worth consideration. So that, after all, when we say that dwarf fruit trees are not a commercial success we mean merely that they will not take the place of standard trees. The large market orchards must always continue to be made up of standard trees; but in their own way the dwarf trees will find a limited place even in commercial operations, and this use of them seems destined to be more general in the future than it has been in the past.