полная версия

полная версияSamuel Pepys and the World He Lived In

Mr. (afterwards Sir Henry) Sheres is frequently referred to in the latter pages of the “Diary,” but the friendship which sprang up between him and Pepys dates from a period subsequent to the completion of that work. Sheres accompanied the Earl of Sandwich into Spain, where he acquired that Spanish character which clung to him through life. He returned to England in September, 1667, carrying letters from Lord Sandwich. Pepys found him “a good ingenious man,” and was pleased with his discourse.

In the following month Sheres returned to Spain, being the bearer of a letter from Pepys to Lord Sandwich.184 Subsequently he was engaged at Tangier, and received £100 for drawing a plate of the fortification, as already related.185 He was grateful to Pepys for getting him the money, and had a silver candlestick made after a pattern he had seen in Spain, for keeping the light from the eyes, and gave it to the Diarist.186 On the 5th of April, 1669, he treated the Pepys household, at the Mulberry Garden, to a Spanish olio, a dish of meat and savoury herbs, which they greatly appreciated.

On the death of Sir Jonas Moore, Pepys wrote to Colonel Legge (afterward Lord Dartmouth) a strong letter of recommendation in favour of Sheres, whom he describes “as one of whose loyalty and duty to the King and his Royal Highness and acceptance with them I assure myself; of whose personal esteem and devotion towards you (Col. Legge), of whose uprightness of mind, universality of knowledge in all useful learning particularly mathematics, and of them those parts especially which relate to gunnery and fortification; and lastly, of whose vigorous assiduity and sobriety I dare bind myself in asserting much farther than, on the like occasion, I durst pretend to of any other’s undertaking, or behalf of mine.”187 Sheres obtained the appointment, and served under Lord Dartmouth at the demolition of Tangier in 1683. He appears to have been knighted in the following year, and to have devoted himself to literature in later life. He translated “Polybius,” and some “Dialogues” of Lucian, and was the author of a pretty song. His name occurs among those who received mourning rings on the occasion of Pepys’s death.

Raleigh said, “There is nothing more becoming any wise man than to make choice of friends, for by them thou shalt be judged what thou art.” If so, it speaks well for Pepys that the names of most of the worthies of his time are to be found amongst his correspondents. Newton and Wallis stand out among the philosophers; the two Gales (Thomas and Roger), Evelyn, and Bishop Gibson among antiquaries and historians; Kneller among artists; and Bishop Compton and Nelson, the author of the “Festivals and Fasts,” among theologians.

The letters of some of these men have been printed in the “Correspondence” appended to the “Diary,” and in Smith’s “Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Samuel Pepys;” but many more still remain in manuscript in various collections.

CHAPTER VIII.

THE NAVY

“Our seamen, whom no danger’s shape could fright,Unpaid, refuse to mount their ships for spite,Or to their fellows swim on board the Dutch,Who show the tempting metal in their clutch.”Marvell’s Instructions to a Painter.OUR literature is singularly deficient in accounts of the official history of the navy. There are numerous books containing lives of seamen and the history of naval actions, but little has been written on the management at home. The best account of naval affairs is to be found in the valuable “Tracts” of the stout old sailor Sir William Monson, which are printed in “Churchill’s Voyages.”188

Sir William was sent to the Tower in 1616, and his zeal in promoting an inquiry into the state of the navy, contrary to the wishes of the Earl of Nottingham, then Lord High Admiral, is supposed to have been the cause of his trouble.

The establishment of the navy, during a long period of English history, was of a very simple nature. The first admiral by name in England was W. de Leybourne, who was appointed to that office by Edward I., in the year 1286, under the title of “Admiral de la Mer du Roy d’Angleterre,” and the first Lord High Admiral was created by Richard II. about a century afterwards. This word “admiral” was introduced into Europe from the East, and is nothing more than the Arabic amir-al189 (in which form the article is incorporated with the noun). The intrusive d, however, made its appearance at a very early period. The office of “Clerk of the King’s Ships,” or “of the Navy,” afterwards “Clerk of the Acts of the Navy,” is in all probability a very ancient one, but the first holder of the office whose name Colonel Pasley, R.E.,190 has met with, is Thomas Roger or Rogiers, who lived in the reigns of Edward IV., Edward V., and Richard III. In the third volume of Pepys’s MS. “Miscellanies” (page 87) is an entry of an order, dated 18th May, 22 Edw. IV. (1482), to the Treasurer and Chamberlain of the Exchequer, to examine and clear the account of “our well beloved Thomas Roger, Esq., Clerk of our Ships.” In Harleian manuscript 433, which is believed to have belonged to Lord Burghley, there is a register of grants passing the Great Seal during the reigns of Edward V. and Richard III., and No. 1690 contains the appointment of “Thomas Rogiers to be clerc of all maner shippes to the King belonging.” It has no date, but is very probably a reappointment by Richard III. on his assumption of the crown.

The navy owes much to Henry VIII., who reconstituted the Admiralty, founded the Trinity House, and established the dockyards at Deptford, Woolwich, and Portsmouth. The origin of the board of “Principal Officers and Commissioners of the Navy,” commonly called in later times “the Navy Board,” dates from his reign. His predecessors had usually themselves managed whatever naval force they possessed, assisted by their Privy Council, and by the officer already alluded to, who was styled “Clerk” or “Keeper” of the King’s ships, but in Henry’s time the rapidly increasing magnitude and importance of the navy rendered a more complete and better organized system of management necessary. To supply this want several new offices were created, and before Henry’s death we find, in addition to the Lord High Admiral and the Clerk of the Ships, a Lieutenant (or Vice-Admiral), a Treasurer, a Comptroller, and a Surveyor of the Navy,191 as well as a Keeper of the Naval Storehouses at Erith and Deptford.192 A few years later we meet with a “Master of the Ordnance of the Ships.” This last office, which had been held by Sir William Woodhouse, was granted by Philip and Mary in 1557 to William (afterwards Sir William) Winter in addition to that of Surveyor, to which he had been appointed by Edward VI.193

Each of these officers must have received some sort of instructions for his guidance, but no general code of rules for the administration of the navy was framed until after the accession of Elizabeth, who issued, about 1560, a set of regulations for “the Office of the Admiralty and Marine Causes,” with the following preamble:194—“Forasmuch as since the erection of the said office by our late dear father Henry VIII., there hath been no certain ordinance established so as every officer in his degree is appointed to his charge: and considering that in these our days our navy is one of the chiefest defences of us and our realm against the malice of any foreign potentate: we have therefore thought good by great advice and deliberation to make certain ordinances and decrees, which our pleasure and express commandment is that all our officers shall on their parts execute and follow as they tender our pleasure, and will answer to the contrary.”

Then follows a list of the several officers at that time forming the Board, viz.:—

1. The Vice-Admiral.

2. The Master of the Ordnance and Surveyor of the Navy: one officer.

3. The Treasurer.

4. The Comptroller.

5. The General Surveyor of the Victuals.

6. The Clerk of the Ships.

7. The Clerk of the Stores.195

The officers were to meet at least once a week at the office on Tower Hill, to consult, and take measures for the benefit of the navy, and were further directed to make a monthly report of their proceedings to the Lord Admiral.

The particular instructions which follow are brief, and by no means explicit:—

1. The Master of the Ordnance is to take care to make the wants of his department known to the Lord Admiral in good time, and he is to obtain the signatures of three of his colleagues every quarter to his books and accounts, which are then to be submitted to the Court of Exchequer.

2. The Treasurer is to make no payments except on the warrant of at least two of his colleagues, and his books are to be made up and certified by a similar number of the officers every quarter.

3. The Surveyor-General of the Victuals is to have his issues warranted, and his accounts certified in the same manner. He is to take care always to have in store a sufficient stock of victuals to supply a thousand men at sea for one month at a fortnight’s notice.

4. The Surveyor, Comptroller, Clerk of the Ships, and Clerk of the Stores are to see the Queen’s ships grounded and trimmed from time to time, and to keep them in such order that upon fourteen days’ warning twelve or sixteen sail may be ready for sea, and the rest soon after. They are to make a monthly report of the state of the ships to the Vice-Admiral and the other officers.

5. The Clerk of the Ships is to provide timber and other materials for building and repairing ships.

6. The Clerk of the Stores is to keep a perfect record of receipts and issues: the latter to be made on the warrant of at least two of the officers.

This most interesting and important document is concluded in the following words:—

“Item, our pleasure and commandment is that all our said officers do agree in one consultation, and all such necessary orders as shall be taken amongst them from time to time to be entered in a ledger book for the whole year, to remain on record.

“The assistants not to be accounted any of our head officers, but yet to travel in our courses when they shall be thereunto commanded or appointed by our Lord Admiral or Vice Admiral, or other our officers.

“Item, our mind and pleasure is that every of our said officers shall see into their fellows’ offices, to the intent that when God shall dispose His will upon any of them they living may be able, if we prefer any of them, to receive the same.

“These our ordinances to be read once a quarter amongst our officers, so as thereby every of them may the better understand his duty, and to be safely kept in our Consultation house at Tower Hill.”

We will now return to Sir William Monson, who, in his “Naval Tracts,” answers the question what kind of men are to be chosen for the various offices. He suggests that “the Comptroller’s and Clerk’s places be reduced into one, who should be an experienced clerk, long bred in the office.... Provided always, that besides their experience and abilities to perform the active part of His Majesty’s service, these men be of good substance and esteem in their estates.”

Such a rule as this would have excluded Pepys from the service, as he knew nothing of the navy when he was made Clerk of the Acts. He soon, however, made himself master of his business, and at the time of his death he was esteemed the greatest authority on naval affairs. In illustration of Monson’s recommendation, it may be remarked that in 1585 the two offices of Clerk and Comptroller were held by the same man, William Borough.

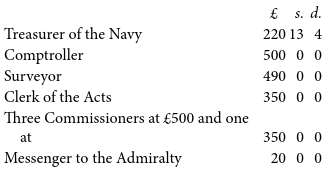

The salaries received by the various officers are set down by Monson as follows:—

196These amounts were made up of the “Fee out of the Exchequer” (or salary proper); the Allowance for one or more Clerks; “Boat-hire,” and “Riding Costs” (or travelling expenses).—C. P.

Although the salary of the Clerk of the Acts is here put at over one hundred pounds, yet the ancient “fee out of the Exchequer,” which was attached to the office, did not amount to more than £33 6s. 8d. per annum, and this sum is specially set forth in Pepys’s patent.

In July, 1660, the salaries of the officers of the navy (with the exception of that of the Treasurer) were advanced, Pepys’s being raised to £350.196 The salary of the Treasurer remained the same, but this was but a small part of his emoluments, which amounted in all to several thousand pounds a year.197

In the Pepysian Library there is preserved the pocket-book of James II., from which I have been allowed to extract the following memorandum of salaries:—

When the Duke of Buckingham was assassinated, in 1628, the office of Lord High Admiral was for the first time put into commission. All the great officers of State were Commissioners, and Edward Nicholas, who had been secretary to Lord Zouch and to the Duke of Buckingham, was appointed Secretary of the Admiralty.

During the Commonwealth both the Admiralty and the Navy Office were administered by bodies of Commissioners. The offices of Comptroller, Surveyor, and Clerk of the Acts were abolished, and although the Treasurer remained, he was not a member of the Navy Board. Robert Blackburne, who was Secretary to most of the Commissions of the Admiralty, entertained Pepys after the Restoration with an account of the doings of the members. He told him that Sir William Penn got promotion by making a pretence of sanctity; and he then mimicked the actions of the Commissioners, who, he affirmed, would ask the admirals and captains respecting certain men, and say with a sigh and a casting up of the eyes, “Such a man fears the Lord;” or, “I hope such a man hath the Spirit of God.”198

At the Restoration the Duke of York was appointed Lord High Admiral, and all powers formerly granted to the Admiralty and Navy Board were recalled.199 By the Duke’s advice a committee was named to consider a plan proposed by himself for the future regulation of the affairs of the navy; and at a court held on July 4th, 1660, three new commissioners (John Lord Berkeley, Sir William Penn, and Peter Pett) were appointed to assist the four principal officers. Pett was to be employed at Chatham dockyard, but the other two had no special duties assigned to them, although their appointment gave them equal power with the original members when they attended at the Board. As there was at this time no half-pay, these appointments were considered as affording a convenient means of granting a comfortable subsistence to an admiral when not at sea. Lord Clarendon strongly disapproved of this innovation, and attributed the idea to Sir William Coventry, who wished to reduce the power and emoluments of the Treasurer.200

In January, 1661–62, James Duke of York issued Instructions which were founded on those drawn up by the Earl of Northumberland, Lord High Admiral from 1638 to 1644, and remained in force until the reorganization of the Admiralty at the beginning of the present century.

It is here necessary to stop a moment for the purpose of noticing Pepys’s relation to these Instructions. Before the publication of the “Diary” it was supposed that he was the chief author of the Rules. In the first Report of the Commissioners of Naval Revision (13th June, 1805) it is distinctly stated that he drew them up under the direction of the Duke, and even Lord Braybrooke makes the claim in regard to Pepys’s authorship. This is an error, and Colonel Pasley points out that at the date of the issue of the Regulations Pepys was by no means on intimate terms with James. Even two years later (4th March, 1633–34) he writes, “I never had so much discourse with the Duke before, and till now did ever fear to meet him;” but what really settles the matter is, that under date February 5th, 1661–62, Pepys writes: “Sir G. Carteret, the two Sir Williams, and myself all alone reading of the Duke’s institutions for the settlement of our office, whereof we read as much as concerns our own duties, and left the other officers for another time.” The latter of these important passages was not printed by Lord Braybrooke, and is only to be found in the Rev. Mynors Bright’s transcript.201

The Navy Office, as we see from the “Diary,” was by no means a happy family. Each officer was jealous of his fellow, and this jealousy was somewhat fostered by the duties enjoined. Pepys constantly complains of the neglect by his colleagues of their several duties, and when the Duke of York returned from his command at the end of the first great Dutch war, he found the office in the greatest disorder. This caused the preparation of the Diarist’s “great letter” to the Duke, which is referred to in the “Diary,” on November 17th, 1666. A still more important letter, on the same subject, written by Pepys, but purporting to come from the pen of the Duke of York, was not prepared until nearly two years after this.202 We learn from the “Diary” all the stages of progress of this letter, the effect it produced when read out at the office,203 and the way in which the officers prepared their answers.204 In his allusion to this letter, Lord Braybrooke again does some injustice to James, for he writes: “We even find in the ‘Diary,’ as early as 1668, that a long letter of regulation, produced before the Commissioners of the Navy by the Duke of York as his own composition, was entirely written by the Clerk of the Acts.”

Colonel Pasley very justly observes, in commenting on this view of the Lord High Admiral’s position:—“There is nothing unusual or improper in a minister, or head of a department, employing his subordinates to prepare documents for his signature, and in this particular instance it was evidently of importance that the actual author should remain unknown. Not only was Pepys himself most anxious to avoid being known in the matter, but it is obvious that the authority and effect of the reprimand and warning would have been much lessened, if the other members of the Board had been aware that the Duke had no other knowledge of the abuses of the office than what Pepys told him. It seems from the ‘Diary,’ that about 1668 Pepys first obtained the complete confidence of the Duke—a confidence which he always after retained and never abused. It is evident from numerous remarks in his manuscripts that Pepys had the highest respect for James’s opinion in naval matters. In fact, the mutual respect and friendship of these two men was equally honourable to both, and it is a mistake to endeavour to magnify one at the expense of the other.”

The letter referred to is in the British Museum,205 and as it is of considerable interest in the life of Pepys, it will be worth while to devote a small space to a few notes on its contents.

James refers to his former letter of January 2nd, 1661, sent with the “Instructions,” as well as to that of March 22nd, 1664, and, after some general remarks, he points out the particular duty of each officer, finishing with remarks on their joint duties as a Board. The letter is drawn up in so orderly a manner, and discovers so thorough a knowledge of the details of the office, that there is little cause for surprise that the officers suspected Pepys to be the author. Article by article of the “Instructions” are set down, and following each of them are remarks on the manner in which it had been carried out. It is very amusing to notice the tact with which our Diarist gets over the difficulty of criticizing his own deeds. The Duke is made to say that although he has inquired as to the execution of the office of Clerk of the Acts, he cannot hear of any particular to charge him with failure in his duty, and as he finds that the Clerk had given diligent attendance, he thinks that the duty must have been done well, particularly during the time of the war, when, in spite of the work being greater, the despatch was praiseworthy. Yet he would not express further satisfaction, but would be willing to receive any information of the Clerk’s failures which otherwise might have escaped his knowledge. The officers were informed that an answer was required from each of them within fourteen days. When these answers were received, Pepys set to work to write a reply for the Duke to acknowledge. Matthew Wren, the Duke’s secretary, smoothed down the language of this letter206 a little, but it still remained a very stinging reprimand. These two letters form, probably, the most complete instance of a severe “wigging” given by the head of an office to his staff.

We will now return to the consideration of the business management of the navy, and it is necessary for us to bear in mind that the offices of the Admiralty and of the Navy Board were quite distinct in their arrangements. The Navy Board formed the Council of the Lord High Admiral, and the Admiralty was, originally, merely his personal office, the locality of which changed with his own change of residence, or that of his secretary. It was at one time in Whitehall, at another in Cannon Row, Westminster; and when Pepys was secretary, it was attached to his house in York Buildings.

When, however, there was a Board of Admiralty in place of a Lord High Admiral, the Admiralty Office became of more importance, and the Navy Office relatively of less.

According to Pepys, there was some talk of putting the office of Lord High Admiral into commission in the year 1668,207 but it was not so treated until June, 1673, when the Duke of York laid down all his offices. The Commissioners on this occasion were Prince Rupert, the three great officers of State, three dukes, two secretaries, Sir G. Carteret, and Edward Seymour (afterwards Speaker of the House of Commons); and Pepys was the secretary. Before the commission passed the Great Seal, the King did the business through the medium of Pepys.208

Lords of the Admiralty were occasionally appointed to assist the Lord High Admiral, or to fill his place while he was abroad. Pepys refers to such Lords on November 14th, 1664, and in March of the following year he remarks: “The best piece of news is, that instead of a great many troublesome Lords, the whole business is to be left with the Duke of Albemarle to act as Admiral.”209

These lords were not properly commissioners, as a commission was only appointed by the King when the office of Lord High Admiral was vacant, but they formed a deputation or committee appointed by the Admiral to act as his deputies.

Pepys was with the Duke of York previous to the reinstatement of the latter as Lord High Admiral, he returned to the office with his patron, and he continued secretary until the Revolution, when he retired into private life. On the Duke’s accession to the throne a new board was formed and the navy was again raised to a state of efficiency.

Pepys was Clerk of the Acts from 1660 to 1672, that is, during the whole period of the “Diary,” and three years afterwards. He was succeeded by his clerk, Thomas Hayter, and his brother John Pepys, who held the office jointly. As already stated, Pepys was promoted to be Secretary of the Admiralty in 1672, and continued in office until 1679, when he was again succeeded for a time by Hayter. We know comparatively little of him in the higher office, and it is as Clerk of the Acts that he is familiar to us. With regard to this position it is necessary to bear in mind that the “so-called” clerk, as well as being secretary, was also a member of the Board, and one of the “principal officers.” On one occasion Pepys met Sir G. Carteret, Sir J. Minnes, and Sir W. Batten at Whitehall, and when the King spied them out, he cried, “Here is the Navy Office!”210

I have already mentioned that the principal officers were superseded during the Commonwealth. Again, in 1686, they were suspended, and the offices were temporarily placed under a body of equal commissioners.

The Navy Office, where Pepys lived during the whole period over which the “Diary” extends, was situated between Crutched Friars and Seething Lane, with an entrance in each of these places. The ground was originally occupied by a chapel and college attached to the church of Allhallows, Barking, but these buildings were pulled down in the year 1548, and the land was used for some years as a garden plot.

In Elizabeth’s reign, when the celebrated Sir William Wynter, Surveyor of Her Majesty’s Ships, brought home from sea much plunder of merchants’ goods, a storehouse of timber and brick was raised on this site for their reception. In course of time the storehouse made way for the Navy Office, a rather extensive building, in which the civil business of the navy was transacted until the last quarter of the eighteenth century. On July 4th, 1660, Pepys went with Commissioner Pett to view the houses, and was very pleased with them, but he feared that the more influential officers would shuffle him out of his rights. Two days afterwards, however, he went with Mr. Coventry and Sir G. Carteret to take possession of the place; still, although his mind was a little cheered, his hopes were not great. On July 9th, he began to sign bills in his office, and on the 18th he records the fact that he dined in his own apartments.