полная версия

полная версияSoil Culture

Young beets are universally esteemed. To have them of excellent quality during all the winter, it is only necessary to plant on the last days of July. If the weather be dry, water well, so as to get them up, and they will attain the size and age at which they are most valued. Keep them in the cellar for use, as other beets. They will keep as well as old ones.

Field-Culture.—Make the soil very mellow, fifteen to eighteen inches deep. Soil having a little sand in its composition is always best. Even very sandy land is good if it be sufficiently enriched. Choose land on which water will not stand in a wet season. Beets endure drought better than extreme wet. Having made the surface perfectly mellow, and free from clods, weeds, and stones, sow in drills, with a machine for the purpose, two feet apart. This is wide enough for a small cultivator to pass between them. After planting, roll the surface smooth and level; this will greatly facilitate early cultivation. On a rough surface you can not cultivate small plants without destroying many of them; hence the necessity of straight rows and thorough rolling. The English books recommend planting this and other roots on ridges: for their climate it is good, but for ours it is bad. They have to guard against too much moisture, and we against drought; hence, they should plant on ridges, and we on an even surface. To get the largest crop, plow a deep furrow for each row, put in plenty of good manure, cover it with the plow and level the surface, and plant over the manure. When well growing, they should be thinned to six or eight inches in the row. Often stirring the earth while they are young is of great benefit. The quality and quantity of a root-crop depend much upon the rapidity of its growth. Slow growth gives harder roots of worse flavor, as well as a stinted crop.

Harvesting should be done just before severe frosts. They will grow until frost comes, however early they were planted, or whatever size they may have attained. They grow as rapidly after light frosts as at any time in the season; but very severe frosts expose them to rot during winter.

Preserving for table use is usually done by putting in boxes with moist sand, or the mould in which they grew. This excludes air, and, if kept a little moist, will preserve them perfectly. Roots are always better buried below frost out-door on a dry knoll, where water will not stand in the pits. But in cold climates it is necessary to have some in the cellar for winter use. The common method of burying beets, and turnips, and all other roots out-door, is well understood. The only requisites are, a dry location secured from frost, straw next the roots, a covering of earth, not too deep while the weather is yet mild; as it grows cold, put on another covering of straw, and over it a foot of earth; as it becomes very cold, put on a load or two of barnyard manure: this will save them beyond the power of the coldest winter. Vast quantities of roots buried outdoor are destroyed annually by frost, and there is no need of ever losing a bushel. You "thought they would not freeze," is not half as good as spending two hours' time in covering, so that you know they can not freeze. There is hardly a more provoking piece of carelessness, in the whole range of domestic economy, than the needless loss of so many edible roots by frost.

The table use of beets is everywhere known; their value for feeding animals is not duly appreciated in this country. No one who keeps domestic animals or fowls should fail to raise a beet-crop; it is one of the surest crops grown; it is never destroyed by insects, and drought affects it but very little. On good soil, beets produce an enormous weight to the acre. The lower leaves may be stripped off twice during the season, to feed to cows or other stock, without injury to the crop. Cows will give more milk for fifteen days, fed on this root alone, than on any other feed; they then begin to get too fat, and decline in milk: hence, they should be fed beets and hay or other food in about equal parts, on which they will do better than in any other way. Horses do better on equal parts of beet and hay than on ordinary hay and grain. Horses fed thus will fatten, needing only the addition of a little ground grain, when working hard. Plenty of beets, with a little other food, makes cows give milk as well as in summer. Raw beets cut fine, with a little milk, will fatten hogs as fast as boiled potatoes. All fowls are fond of them, chopped fine and mixed with other food. Sheep, also, are fond of them. They are very valuable to ewes in the spring when lambs come, when they especially need succulent food. The free use of this root by English farmers is an important reason of their great success in raising fine sheep and lambs. They promote the health of animals, and none ever tire of them. As it needs no cooking, it is the cheapest food of the root kind. Beets will keep longer, and in better condition, than any other root. They never give any disagreeable flavor to milk. It is considered established, now, that four pounds of beet equal in nourishment five pounds of carrot. Every large feeder should have a cellar beyond the reach of frosts, and of large dimensions, accessible at all times, in which to keep his roots. These beets should be piled up there as cord-wood, to give a free circulation of the air.

In Germany, the beet-crop takes the place of much of their meadows, at a great saving of expense, producing remarkably fine horses, and fattening immense herds of cattle, which they export to France. We insist upon the importance of a beet-crop to every man who owns an acre of land and a few domestic animals, or only a cow and a few fowls.

BENE PLANT

Introduced into the Southern states by negroes from Africa. They boil a handful of the seed with their allowance of Indian corn. It yields a larger proportion than any other plant of an excellent oil. It is extensively cultivated in Egypt as food for horses, and for culinary purposes. It is remarkable that this native of a southern clime should flourish well, as it does, in the Northern states. It should be cultivated throughout the North as a medicinal herb.

A Virginia gentleman gave Thorburn & Son, seed-dealers of New York, the following account of its virtues: a few green leaves of the plant, plunged a few times in a tumbler of cold water, made it like a thin jelly, without taste or color. Children afflicted with summer-complaint drink it freely, and it is thought to be the best remedy for that disease ever discovered; it is believed that three thousand children were saved by it in Baltimore the first summer after its introduction. Plant in April, in the middle states, about two feet apart. When half grown, break off the plants, to increase the quantity of leaves. We recommend to all families to raise it, and try its virtues, under the advice of their family physicians.

BIRDS

These are exceedingly useful in destroying insects. So of toads and bats. No one should ever be wantonly killed. Boys, old or young, should never be allowed to shoot birds, or disturb their nests, only as they would domestic fowls, for actual use. A wanton recklessness is exhibited about our cities and villages, in killing off small birds, that are of no use after they are dead. Living, they are valuable to every garden and fruit-orchard. In every state, stringent laws should be made and enforced against their destruction. Even the crow, without friends as he is, is a real blessing to the farmer: keep him from the young corn for a few days, as it is easy to do, and, all the rest of the year, his destruction of worms and insects is a great blessing. Birds, therefore, should be baited, fed, and tamed, as much as possible, to encourage them to feel at home on our premises. Having protected our small fruits, they claim a share, and they have not always a just view of the rights of property, nor do they always exhibit good judgment in dividing it. It is best to buy them off by feeding them with something else. If they still prefer the fruit, hang little bells in the trees, where they will make a noise; or hang pieces of tin, old looking-glass, or even shingles, by strings, so that they will keep in motion, and the birds will keep away. Images standing still are useless, as the birds often build nests in the pockets.

BLACKBERRY

This berry grows wild, in great abundance, in many parts of the country. It has been so plentiful, especially in the newer parts, that its cultivation has not been much attended to until recently. Like all other berries, the cultivated bear the largest and best fruit.

Uses.—It is one of the finest desert berries; excellent in milk, and for tarts, pies, &c. Blackberries make the best vinegar for table use, and a wine that retains the peculiar flavor, and of a beautiful color.

This berry comes in after the raspberries, and ripens long in succession on the same bush.

High-bush Blackberry.

Varieties of wild ones, usually found growing in the borders of fields and woods, are the low-bush and the high-bush. Downing gives the first place to the low. Our experience is, that the high is the best bearer of the best fruit. We have often gathered them one and one fourth inches in length, very black, and of delicious sweetness. The low ones that have come under our observation have been smaller and nearer round, and not nearly so sweet.

The best cultivated varieties are—

The Dorchester—Introduced from Massachusetts, and a vigorous, large, regular bearer.

Lawton, or New Rochelle.—This is the great blackberry of this country, by the side of which, no other, yet known, need be cultivated. It is a very hardy, great grower. It is an enormous bearer of such fruit that it commands thirty cents per quart, when other blackberries sell for ten. On a rather moist, heavy loam, and especially in the shade, its productions are truly wonderful. Continues to ripen daily for six weeks.

Propagation is by offshoots from the old roots, or by seeds. When by seeds, they should be planted in mellow soil, and where the sun will not shine on them between eight and five o'clock in hot weather. In transplanting, much care is requisite. The bark of the roots is like evergreens, very tender and easily broken, or injured by exposure to the atmosphere; hence, take up carefully, and keep covered from sun and air until transplanted. This is destined to become one of the universally-cultivated small fruits—as much so as the strawberry. The best manures are, wood-ashes, leaves, decayed wood, and all kinds of coarse litter, with stable manure well incorporated with the soil, before transplanting. Animal manure should not be very plentifully applied.

We have seen in Illinois a vigorous bush, and apparently good bearer, of perfect fruit—a variety called white blackberry. The fruit was greenish and pleasant to the taste.

BLACK RASPBERRY

The common wild, found by fences, especially in the margin of forests, in most parts of the United Sates, is very valuable for cultivation in gardens. Coming in after the red raspberry, and ripening in succession until the blackberry commences, it is highly esteemed. Cultivated with little animal manure, but plenty of sawdust, tan-bark, old leaves, wood, chips, and coarse litter, it improves very much from its wild state. Fruit is all borne on bushes of the previous year's growth; hence, after they have done bearing, cut away the old bushes. To secure the greatest yield on rich land, cut off the tops of the shoots rising for next year's fruit, when they are four or five feet high. The result will be, strong shoots from behind all the leaves on the upper part of the stalk, each of which will bear nearly as much fruit as would the whole have done without clipping. A dozen of these would occupy but a small place in a border, or by a wall. Not an American garden should be found without them.

BONES

Bones are one of the most valuable manures. They yield the phosphates in large measure. On all land needing lime, they are very valuable. The heads, &c., about butchers' shops will bear a transportation of twenty miles to put upon meadows. Break them with the head of an axe, and pound them into the sod, even with the surface. They add greatly to the products of a meadow. Ground, they make one of the best manures of commerce. A cheap method for the farmer is to deposite a load of horse-manure, and on that a load of bones, and alternate each, till he has used up all his bones. Cover the last load of bones deep with manure. It will make a splendid hotbed, and the fermentation of the manure will dissolve or pulverize the bones, and the heap will become one mass of the most valuable manure, especially for roots and vines, and all vegetables requiring a rich, fine manure.

BORECOLE, OR KALE

There are some fifteen or twenty kinds cultivated in Europe. Two only, the green and the brown, are desirable in this country. Cultivate as cabbage. In portions of the middle states they will stand the frosts of winter well, without much protection; further north, they need protection with a little brush and straw during severe frosts. Those grown on rather hard land are better for winter; being less succulent, they endure cold better. Cut them off for use whenever you choose. They do not head like cabbage; they have full bunches of curled leaves. Cut off so as to include all, not over eight inches long. In winter, after having been pretty well exposed to the frost, they are very fine. Set out the stumps early in spring, and they will yield a profusion of delicious sprouts. This would be a valuable addition to many of our kitchen gardens.

BROCCOLI

This may be regarded as a late flowering species of cauliflower. It should be planted and treated as cabbage, and fine heads will be formed, in the middle states, in October: at the South much earlier, according to latitude. Take up in November, and preserve as cabbage, and good ones may be had in winter. To prevent ravages of insects, mix ashes in the soil when transplanting, or fresh loam or earth from a new field; or trench deep, so as to throw up several inches of subsoil, which had not before been disturbed.

To save seed, transplant some of the best in spring; break off all the lower sprouts, allowing only a few of the best centre ones to grow. Tie them to stakes, to prevent destruction by storms. Be sure to have nothing else of the cabbage kind near your seed broccoli.

BROOM CORN

Cultivated like other corn, only that this is more generally planted in drills. Three feet apart, and six inches in the drill, it yields more weight of better corn to the acre than to have it nearer. The great fault in raising this crop is getting it too thick. The finest-looking brush is of corn cut while yet so green that the seed is useless. But the brush is stronger, and will make better brooms for wear, when the corn is allowed to stand until the seed is hard, though not till the brush is dry. The land should be rich. This is a hard, exhausting crop for the soil. To harvest, bend down, two feet from the ground, two rows, allowing them so to fall across each other as to expose all the heads. Cut off the heads, with six or eight inches of the stalk, and place them on top of the bent rows to dry. In a week, in dry weather, they will be well cured, and should be then spread thin, under cover, in plenty of air. There is no worse article to heat and mould. In large crops, they usually take off the seed before curing; it is much lighter to handle, and less bulky. It may be done then, or in winter, as you prefer. The seed is removed on a cylinder eighteen inches long, and two and a half feet in diameter, having two hundred wrought nails with their points projecting. It is turned by a crank, like a fanning mill. The corn is held in a convenient handful, like flax on a hatchel. Where large quantities are to be cleaned of the seed, power is used to turn the machine. Ground or boiled, the seed makes good feed for most animals. Dry, it has too hard a shell. Fowls, with access to plenty of gravel, do well on it. Broom-corn is not a very profitable crop, except to those who manufacture their own corn into brooms. There is much labor about it, and considerable hazard of injuring the crop, by the inexperienced; hence, young farmers had, generally, better let it alone. There are two varieties—they may be forms of growth, from peculiar habits of culture—one, short, with a large, stiff brush running up through the middle, with short branches to the top, called pine-top: it is of no value;—the other is a long, fine brush, the middle being no coarser than the outside. It should be planted with a seed-drill, to make the rows straight and narrow for the convenience of cultivation. Harrowing with a span of horses, with a V drag, one front tooth out, as soon as the corn is up, is beneficial to the crop.

BRUSSELS SPROUTS

This is a species of cabbage. A long stem runs up, on which grow numerous cabbage-heads in miniature. The centre head is small and of little use, and the large leaves drop off early. It will grow among almost anything else, without injury to either. It is raised from seed like cabbage, and cultivated in all respects the same. Eighteen inches apart each way is a proper distance, as the plant spreads but little. Good, either as a cabbage, or when very small, as greens. They are good even after very hard frosts. By forwarding in hotbed in the spring, and by planting late ones for winter, they may be had most of the year. If they are disposed to run to seed too early, it may be prevented by pulling up, and setting out again in the shade. Save seed as from cabbage, but use great caution that they are not near enough to receive the farina from any of the rest of the cabbage-tribe.

BUCKTHORN

This is the most valuable of the thorn tribe, for hedge, in this country. It never suffers from those enemies that destroy so much of the hawthorn. This is also used for dyeing and for medicine.

BUCKWHEAT

This will grow well on almost any soil; even that too poor for most other crops will yield very good buckwheat—though rich land is better for this, as for all other crops. The heat of summer is apt to blast it when filling; hence, in the middle states, it is not best to sow it until into July. It fills well in cool, moist weather, and is quite a sure crop if sowed at the right time. On poor land, one bushel of seed is required for an acre, while half a bushel is sufficient on rich land, where stalks grow large.

The blossoms yield to the honey-bee very large quantities of honey, much inferior to that made of white clover; it may be readily distinguished in the comb by its dark color and peculiar flavor. Ground, it is good for most animals, and for fowls unground, mixed with other grain. It remains long in land; but it is a weed easily killed with the hoe; or a farmer may set apart a small field for an annual crop, keeping up the land by the application of three pecks of plaster per acre each year. It is very popular as human food, and always made into pancakes. The free use of it is said to promote eruptive diseases. The India buckwheat is more productive, but of poorer quality. The bran is the best article known to mix with horse-manure and spade into radish beds, to promote growth and kill worms.

BUDDING

This is usually given under the article on peaches. But, as it is a general subject, it should be in a separate article, reserving what is peculiar to the different fruits to be noticed under their respective heads.

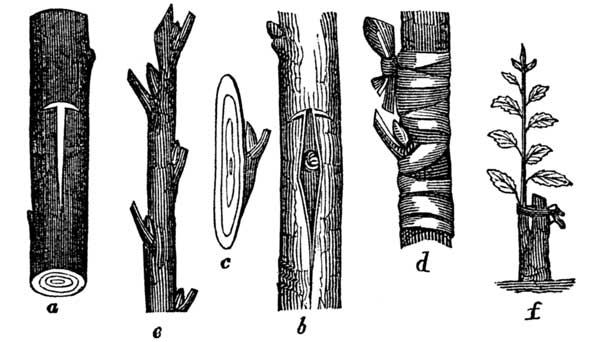

Budding.

Budding small trees should usually be performed very near the ground, and on a smooth place. Any sharp pocket-knife will do; but a regular budding knife, now for sale in most hardware-stores, is preferable. Cut through the bark in the form of a horizontal crescent (a in the cut). Split the bark down from the cut three fourths of an inch, and, with the ivory-end of the knife, raise the corners and edges of the bark. Select a vigorous shoot of this year's growth, but having buds well matured—select a bud that bids fairest to be a leaf-bud, as blossom-buds will fail—insert the knife half an inch below the bud, and cut upward in a straight line, severing the bark and a thin piece of the wood to one half inch above the bud, and let the knife run out: you then have a bud ready for insertion (c in cut). The English method is to remove the wood from the bud before inserting it; this is attended with danger to the vitality of the bud, and is, therefore, less certain of success, and it is no better when it does succeed. Hence, American authorities favor inserting the bud with the wood remaining. Insert the lower end of this slip between the two edges of the bark, passing the bud down between those edges, until the top of the slip comes below the horizontal cut, and remaining contiguous to it. If the bud slip be too long, after it is sufficiently pressed down, cut off the top so as to make a good fit with the bark above the cut (b in cut). The lower end of the bud will have raised the split bark a little more to make room for itself, and thus will set very close to the stalk. Tie the bud in with a soft ligature; commence at the bottom of the split, and wind closely until the whole wound is covered, leaving only the bud exposed (d in cut). It is more convenient to commence at the top, but it is less certain to confine the slip opposite the bud in close contact with the stalk: this is indispensable to success. We have often seen buds adhere well at the bottom, but stand out from the stalk, and thus be ruined.

Preparation of Buds.—Take thrifty, vigorous shoots of this year's growth, with well-matured buds; cut off the leaves one half inch from the stalks (e in cut); wrap them in moist moss or grass, or put them in sawdust, or bury them one foot in the ground.

Bands.—The best yet known is the inside bark of the linden or American basswood. In June, when the bark slips easily, strip it from the tree, remove the coarse outside, immerse the inside bark in water for twenty days; the fibres will then easily separate, and become soft and pliable as satin ribbon. Cut it into convenient lengths, say one foot, and lay them away in a dry state, in which they will keep for years. This will afford good ties for many uses, such as bandages of vegetables for market, &c. Matting that comes around Russia iron and furniture does very well for bands; woollen yarn and candle-wicking are also used; but the bass-bark is best. After ten days the bands should be loosened and retied; then, if the bud is dried, it is spoiled, and the tree should be rebudded in another place; at the end of three weeks, if the bud adheres firmly, remove the band entirely. Better not bud on the south side; it is liable to injury in winter. In the spring, after the swelling of buds, but before the appearance of leaves, cut off the top four inches above the bud; when the bud grows, tie the tender shoot to the stalk (growing bud in cut, f). In July, cut the wood off even with the base of the bud and slanting up smoothly.

Causes of Failure.—If you insert a blossom-bud you will get no shoot, although the bud may adhere well. If scions cut for buds remain two hours in the sun with the leaves on, in a hot day, they will all be spoiled. The leaves draw the moisture from the bud, and soon ruin it. Cut the leaves off at once. If you use buds from a scion not fully grown, very few of them will live; they must be matured. If the top of the branch selected be growing and very tender, use no buds near the top of it. If in raising the bark to make room for the bud, you injure the soft substance between the bark and the wood, the bud will not adhere. If the bud be not brought in close contact with the stalk and firmly confined there, it will not grow. With reasonable caution on these points, not more than one in fifty need fail.

Time for Budding.—This varies with the season. In the latitude of central New York, in a dry season, when everything matures early, bud peaches from the 15th to the 25th of August—plums, &c., earlier. In wet and great growing seasons, the first ten days in September are best. Much budding is lost on account of having been done so late as to allow no time for the buds to adhere before the tree stops growing for the season. If budding is performed too early, the stalk grows too much over the bud, and it gums and dies. It is utterly useless to bud when the bark is with difficulty loosened; it is always a failure.