полная версия

полная версияSoil Culture

The best early string-bean is the Early Mohawk; it will stand a pretty smart spring-frost without injury; comes early, and is good. Early Yellow, Early Black, and Quaker, or dun-colored, are also early and good.

Refugee, or Thousand-to-one, are the best string-beans known; have a round, crisp, full, succulent pod; come as soon as the Mohawks are out of the way; and are very productive. Planted in August, they are excellent until frost; the very best for pickling. For an early shell-bean we recommend the China red-face; the white kidney and numerous other varieties are less certain and productive.

Running Beans are numerous. The true Lima, very large, greenish, when ripe and dry, is the richest bean known; is nearly as good in winter, cooked in the same way, as when shelled green. They are very productive, continuing in blossom till killed by frost. In warm countries they grow for years, making a tree, or growing like a large grapevine.

The London Horticultural—called also Speckled Cranberry, and Wild Goose—is a very rich variety. The only objection is the difficulty of shelling; one only can be removed at once, because of the tenderness of the pod. The Carolina or butter bean often passes for the Lima. It has similar pods, the bean is of similar shape, but always white, instead of greenish like the Lima, and smaller, earlier, and of inferior quality. The Scarlet Runner, formerly only grown as an ornament on account of its great profusion of scarlet blossoms continuing until frost, is a very productive variety; pods very large and very succulent, making an excellent string-bean; a rich variety when dry, but objectionable on account of their dark color. The Red and the White Cranberries, Dutch Caseknife, and many other varieties, have good qualities, but are inferior to those mentioned above. Beans may be forwarded in hotbeds, by planting on sods six inches square, put bottom-up on the hotbed, and covered with fine mould; plant four beans on each sod; when frost is gone, remove the sod in the hill beside the pole, previously set, leave only two pole-beans to grow in a hill; they will always produce more than a greater number. A shrub six feet high, with the branches on, is better than a pole for any running bean; nearly twice as many will grow on a bush as on a pole. Use a crowbar for setting poles, or drive a stake down first, and set poles very deep, or they will blow down and destroy the beans.

BEES AND BEEHIVES

The study of the honey-bee has been pursued with interest from remote ages. A work on bees, by De Montfort, published at Antwerp in 1649, estimates the number of treatises on this subject, before his time, at between five and six hundred. As that was two hundred and eight years ago, the number has probably increased to two thousand or more. We have some knowledge of the character of these early works, as far back as Democritus, four hundred and sixty years before the Christian era. The great men of antiquity gave particular attention to study and writing on the honey-bee.—Among them we notice Aristotle, Plato, Columella, Pliny, and Virgil. At a later period, we have Huber, Swammerdam, Warder, Wildman, &c. In our own day, we have Huish, Miner, Quinby, Weeks, Richardson, Langstroth, and a host of others. For the first two thousand years from the date of these works, the bee was treated mainly as a curious insect, rather than as a source of profit and luxury to man. And although Palestine was eulogized as a land flowing with milk and honey, before the Hebrews took possession of it, yet the science of bee-culture was wholly unknown.

In the earliest attention to bees, they were supposed to originate in the concentrated aroma of the sweetest and most beautiful flowers. Virgil, and others of his time, supposed them to come from the carcasses of dead animals. But the remarkable experiments of Huber, sixty years ago, developed many facts respecting their origin and economy. Subsequent observers have added still more to the stock of our knowledge respecting these wonderful creatures. The different stages of growth, from the minute egg of the queen to a full grown bee, and the precise time occupied by each, are well established. The three classes of bees, in every perfect colony, and the offices of each; their mechanical skill in constructing the different sized and shaped cells, for honey, for raising drones, workers, and queens, all differing according to the purposes for which they are intended; the wars of the queens, and their sovereignty over their respective colonies; the methods by which working-bees will raise a young queen, when the old one is destroyed, out of the larvae of common bees; the peculiar construction and situation of the queen cells; and, above all, the royal jelly (differing from everything else in the hive) which they manufacture for the food of young queens; the manner in which they ventilate their hives by a swift motion of their wings, causing the buzzing noise they make in a summer evening; their method of repairing broken comb, and building fortifications, before their entrances, at certain times, to keep out the sphinx—all these curious matters are treated fully in many of our works on bees. But we must forego the pleasure of presenting these at length, it being our sole object to enable all who follow our directions, so to manage bees as to render them profitable. In preparing the brief directions that follow, we have most carefully studied all the works, American and foreign, to which we could get access. Between this article and the best of those works there will be found a general agreement, except as it respects beehives. We present views of hives, that we are not aware have ever been written. The original idea, or new principle (which consists in constructing the hive with the entrance near the top), was suggested to us by Samuel Pierce, Esq., of Troy, N. Y., who is the great American inventor of cooking-ranges and stoves. We have carefully considered the principle in its various relations to the habits of the bee, and believe it correct. To most of our late works on honey-bees we have one serious objection: it is, that they bear on their face the evidence of having been written to make money, by promoting the sale of some patent hive. These works all have a little in common that is interesting; the remainder seems designed to oppose some former patent and commend a new one. They thus swell their volumes to a troublesome and expensive size, with that which is of no use to practical men. A work made to fight a patent, or to sell one, can not be reliable. The requisites to successful bee-management are the following:—

1. Always have large, strong swarms. Such only are able successfully to contend with their enemies. This is done by uniting weak swarms, or sending back a young, feeble swarm when it comes out (as herein after directed).

2. Use medium-sized hives. In too large hives, bees find it difficult to guard their territories. They also store up more honey than they need, and yield less to the cultivator. The main box should be one foot square by fifteen inches high. Make hives of new boards; plane smooth and paint white on the outside. The usual direction is to leave the inside rough, to aid in holding up the honey, but to plane the inside edges so as to make close joints. We counsel to plane the inside of the hive smooth, and draw a fine saw lightly length wise of the boards, to make the comb adhere. This will be a great saving of the time of bees, when it is worth the most in gathering honey. They always carry out all the sawdust from the inside of their hives. Better save their time by planing it off.

3. To prevent robberies among bees, when a weak colony is attacked, close their entrances so that but one bee can pass at once, and they will then take care of themselves. To prevent a disposition to pillage, place all your hives in actual contact, on the sides, and make a communication between them, but not large enough to allow bees to pass. This will give the same scent to the whole, and make them feel like one family. Bees distinguish strangers only by the smell: hence, so connected, they will not quarrel or pillage.

4. Comb is usually regarded better for not being more than two or three years old. The usual theory is, that cells fill up by repeated use, and, becoming smaller, render the bees raised in them diminutive. This is not probable, as a known habit of the bee is to clean out the cells before reusing them. Huber demonstrated that bees raised in drone-cells (which are always larger than for workers) grew no larger than in their own natural cells. And as bees build their cells the right size at first, it is probable they keep them so. Quinby assures us that bees have been grown twenty years in the same comb, and that the last were as large as the first. But for other reasons, it is better to change the comb. In all ordinary cases, it is better to transfer the swarm to a new hive every third year. Many think it best to use hives composed of three sections, seven and a half inches deep each, screwed together with strips of wood on the sides, and the top screwed on that it may easily be removed; thick paper or muslin should be pasted around, on the places of intersection, to guard against enemies; the two lower sections only allowed to contain bees—the upper one being designed for the honey-boxes, to be removed. Each spring, after two years old, the lower section is taken out and a new one put on the top, the cover of the old one having been first removed. This is the old "pyramidal beehive," which is the title of a treatise on bees, by P. Ducouedic, translated from the French and abridged by Silas Dinsmore in 1829. This has recently been revived and patented as a new thing. We think with Quinby, that these hives are too expensive and too complicated, and that the great mass of cultivators will succeed best with hives of simple construction.

5. Allowing bees to swarm in their own time and way is better than all artificial multiplication of colonies. If there are no small trees near the apiary, place bushes, upon which the bees will usually light, when they come out. If they seem determined to go away without lighting, throw sand or dust among them; this produces confusion, and causes them to settle near. The practice of ringing bells and drumming on tin, &c., is usually ridiculed; but we believe it to be useful, and that on philosophic principles. The object to be secured is to confuse the swarm and drown the voice of the queen. The bees move only with their queen; hence, if anything prevents them from hearing her, confusion follows, and the swarm lights: therefore, any noise among them may answer the purpose, and save the swarm.

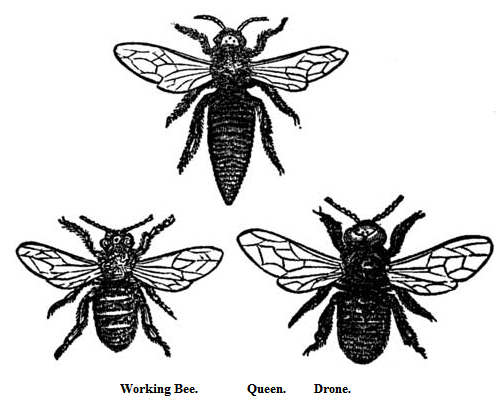

To hive bees, place them on a clean white cloth, and set the hive over them, raised an inch or two by blocks under the corners. It is said that a little sweetened water or honey, applied to the inside of the hive, will incline the bees to remain. The best preparation is to fasten a piece of new white comb on the top of the inside of the hive. This is done by dipping the end of a piece of comb in melted beeswax, and sticking it to the top. Bees should never be allowed to send off more than two colonies in one season. To restrict them to one is still better. Excessive swarming is a precursor of destruction, rather than an evidence (as usually regarded) of prosperity. A given number of bees will make far less honey in two hives than in one, unless they are so numerous as greatly to crowd the hive. When a late swarm comes out, take away the queen, and they will immediately return. Any one may easily find the queen: she is always in the centre of the bunch into which the swarm collects on lighting. If they form two or three clusters, it is because they have that number of queens. Then all the queens should be destroyed. The following cuts of the three classes of bees will enable one to distinguish the queen.

The queen is sometimes, but not always, larger than the common bee; but her body is always longer, and blackish above and yellowish underneath.

To unite any two swarms together, turn the hive you wish to empty bottom-up, and place the one into which you would have them go on the top of the other, with their mouths together; then tie a cloth around, at the place of intersection, to prevent the egress of the bees. Gently rap the lower hive on all sides, near the bottom, gradually rising until you reach the top of the lower hive, and all the bees will go into the upper one.

In the same way, it is easy to remove a colony into a new hive, whenever you think they need changing. This should be performed in the dusk of the evening, and need occupy no more than half an hour. The hive should then be put in its place. Uniting weak new swarms, may be done whenever they come out; but changing a swarm from an old hive to a new one should be performed as early as the middle of June. If moths get in, change hives at any time when it is warm enough for bees to work, and give them all the honey in their old hive. If you discover moths too late for the bees to build comb in a new hive, take the queen from the hive infested with moths, and place it where the bees will unite with another colony, and feed them all the honey from the deserted hive. This, or the destruction of the bees and saving the honey, is always necessary, when moth-worms are in possession, unless they are so near the bottom, that all the comb around them may be cut out. Bees are fond of salt. Always keep some on a board near them.

They also need water. If a rivulet runs near the apiary, it is well. If not, place water in shallow pans, with pebbles in them, on which the bees can stand to drink. Change the water daily. It is too late to speak of the improvidence of killing bees, to get their honey. Use boxes of any size or construction you choose. In common hives, boxes should be attached to the sides, and not placed on the top. It is a wasteful tax upon the time and strength of loaded bees, to make them travel through the whole length of the hive, into boxes on the top. Place boxes as near as possible to their entrance or below that entrance. Bees should be kept out of the boxes until they have pretty well filled the hive, or they may begin to raise young bees in the boxes.

Wintering bees successfully, is one of the most difficult matters in bee-culture. Two evils are to be guarded against, dampness and suffocation. Excessive dampness, sometimes causes frost about the entrance that fills it up and suffocation ensues. Sometimes snow falls, or is blown over the entrance, and the bees die in a few hours for the want of air. Many large colonies, with plenty of honey, are thus destroyed. Dampness is very injurious to bees on other accounts. In a good bee-house there is no danger from snow, and little from dampness. Bees, not having honey enough for winter, should be fed in pleasant fall weather, after they have nearly completed the labors of the season. Weighing hives is unnecessary. A moderate degree of judgment will determine whether a swarm has a sufficient store for winter. If not, feed them. Never give bees dry sugar. They take up their food, as an elephant does water in his trunk; it, therefore, should be in a liquid form. Boil good sugar for ten minutes in ale or beer, leaving it about as thick as honey. Put it in a feed trough; which should be flat-bottomed.

Fasten together thin slats, one fourth of an inch apart, so as to fit the inside of the feed trough and lie on the surface of the liquid, so as to rise and fall with it. Put this in a box and attach it to the hive, as for taking box-honey, and the bees will work it all up. Put out-door, it tempts other bees, and may lead to quarrels, and robbery.

It is not generally known, that a good swarm of bees may be destroyed, by feeding them plenty of honey, early in the spring. They carry it in and fill up their empty cells and leave no room for raising young bees; hence the whole is ruined for want of inhabitants, to take the places of those that get destroyed, or die of age.

To winter bees well, utterly exclude the light during all the cold weather, until it becomes so warm, that they will not get so chilled when out that they can not return. Intense cold is not injurious to bees, provided they are kept in the hive and are dry. A large swarm, will not eat two pounds of honey during the whole cold winter, if kept from the light. When tempted out, every warm day they come into the sunshine and empty themselves, and return to consume large quantities of honey. Kept in the dark, they are nearly torpid, eat but a mere trifle, and winter well. Whatever your hive or house, then, keep your bees entirely from the light, in cold weather. This is the only reason why bees keep so well in a dark dry cellar, or buried in the ground, with something around them, to preserve them from moisture, and a conductor through the surface, to admit fresh air. It is not because it keeps out the cold, but because it excludes the light, and renders the bees inactive. Gilmore's patent bee-house, is a great improvement on this account.

Of the diseases of bees, such as dysentery, &c., we shall not treat. All that can profitably be done, to remedy these evils, is secured by salt, water, and properly-prepared food, as given above.

But the great question in bee-culture is, How to prevent the depredation of the wax-moth? To this subject, much study has been given, and respecting it many theories have been advanced. The following suggestions are, to us, the most satisfactory. The miller, that deposites the egg, which soon changes to the worm, so destructive in the beehive, commences to fly about, at dark. In almost every country-house, they are seen about the lights in the evening. They are still during all the day. They are remarkably attracted by lights in the evening. Hence our first rule:—

1. Place a teasaucer of melted lard or oil, with a piece of cotton flannel for a wick, in or near the apiary at dusk; light it and allow it to burn till near morning, expiring before daylight. This done every night during the month of June, will be very effectual.

2. Keep grass and weeds away from the immediate vicinity of your apiary. Let the ground be kept clean and smooth. This destroys many of the hiding-places of the miller, and forces him away to spend the day. This precaution has many other advantages.

3. Keep large strong colonies. They will be able to guard their territories, and contend with this and all other enemies.

4. Never have any opening in a beehive near the bottom, during the season of millers (see Beehive). Let the openings be so small, that only one or two bees can pass at once. To accommodate the bees, increase the number of openings. Millers will seldom enter among a strong swarm, with such openings. All around the bottom, it should be so tight, that no crevice can be found, in which a miller can deposite an egg. Better plaster around, closely, with some substance, the place of contact between the hive and the board on which it stands, and keep it entirely tight during the time in which the millers are active.

5. If, through negligence, worms have got into a hive, examine it at once; and if they are near the bottom only, within sight and reach, cut out the comb around them, and remove them from the hive. If this is not practicable, transfer the swarm to a new hive, or unite it with another, without delay.

6. The great remedy for the moth is in the right construction of a BEEHIVE.

Whatever the form of the hive you use, have the entrance within three or four inches of the top. Millers are afraid of bees; they will not go among them, unless they are in a weak, dispirited condition. They steal into the hive when the bees are quiet, up among the comb, or when they hang out in warm weather, but are still and quiet. If the hive be open on all sides (as is so often recommended), the miller enters on some side where the bees are not. Now bees are apt to go to the upper part of the hive and comb, and leave the lower part and entrance exposed. If the entrance be at the upper part, the bees will fill it and be all about it. A bee can easily pass through a cluster of bees, and enter or leave a hive; but a miller will never undertake it: this, then, will be a perfect safeguard against the depredations of the moth. This hive is better on every account. Moisture rises: in a hive open only at the bottom, it is likely to rise to the top of the hive and injure the bees; with the opening near the top it easily escapes. The objection that would be soonest raised to this suggestion is, that bees need a good circulation of fresh air, and such a hive would not favor it. To this we reply, a hive open near the top secures the best possible air to the swarm; any foul air has opportunity freely to escape. That peculiar humming heard in a hive in hot weather is produced by a certain motion of the wings of the bees, designed to expel vitiated air, and admit the pure, by keeping up a current. In the daytime, when the weather is hot, you will see a few bees near the entrance on the outside, and hear others within, performing this service, and, when fatigued, others take their place. This is one of the most wonderful things in all the habits and instincts of bees. They thus keep a pure atmosphere in a crowded hive in hot weather. Now, it would require much less fanning to expel bad air from a hive open at the top, than from one where all that air had to be forced down, through an opening at the bottom. This theory is sustained by the natural habits of bees in their wild state. Wild bees, that select their own abodes, are found in trees and crevices of rocks. They usually build their combs downward from their entrance, and their abode is air-tight at the bottom; they have no air only what is admitted at their entrance, near the top of their dwelling, and with no current of air only what they choose to produce by fanning. The purest atmosphere in any room is where it enters and passes out at the top; in such a room only does the external atmosphere circulate naturally. It is on the same principle that bees keep better buried than in any other way, provided only they are kept dry. Yet they are in a place air-tight, except the small conductor to the atmosphere above them. The old "pyramidal beehive" of Ducouedic, with three sections, one above the other, allowing the removal of the lower one each spring, and the placing of a new one on the top—thus changing the comb, so that none shall ever be more than two years old, with the opening always within three or four inches of the top, is the best of the patent hives. We prefer plain, simple hives. The general adoption of this principle, whatever hives are used, would be a new era in the science of bee-culture. No beehive should ever be exposed to the direct rays of the sun in a beehouse. A hive standing alone, with a free circulation of air on every side, will not be seriously injured by the sun. But when the rays are intercepted by walls or boards, in the rear and on the sides, they are very disastrous. Other hints, such as clearing off occasionally, in all seasons except in the cold of winter, the bottom board, &c., are matters upon which we need not dwell. No cultivator would think of neglecting them. Let no one be alarmed at finding dead bees on the bottom when clearing out a hive; bees live only from five to seven months, and their places are then supplied with young ones. The above suggestions followed, and a little care taken in cultivating the fruits, grains, and grasses, that yield the best flowers for bees, would secure uniform success in raising honey. This is one of the finest luxuries; and, what is a great desideratum, it is within the easy reach of every poor family, even, in all the rural districts of the land.

Good honey, good vegetables, and good fruit, like rain and sunshine, may be the property of all. The design of this volume is to enable the poor and the unlearned to enjoy these things in abundance, with only that amount of care and labor necessary to give them a zest.

BEETS

Of this excellent root there are quite a number of varieties. Mangel-Wurtzel yields most for field-culture, and is the great beet for feeding to domestic animals; not generally used for the table. French Sugar or Amber Beet is good for field-culture, both in quality and yield; but it is not equal to the Wurtzel. Yellow-Turnip-rooted, Early Blood-Turnip-rooted, Early Dwarf Blood, Early White Scarcity, and Long Blood, are among the leading garden varieties. Of all the beets, three only need be cultivated in this country—the Wurtzel for feeding, and the Early Blood Turnip-rooted and Long Blood for the table. The Early Blood is the best through the whole season, comes early, and can be easily kept so as to be good for the table in the spring. The Long Blood is later, and very much esteemed. Beets may be easily forwarded in hotbeds. Sow seed early, and transplant in garden as soon as the soil is warm enough to promote their growth. When well done, the removal retards their growth but little.