полная версия

полная версияIn Château Land

As Blois is only about an hour from Tours, we reached here some time before Archie appeared, and thus had time to feel quite at home in this pleasant little hotel, and to kill the fatted calf in honor of his arrival. This latter ceremony was exceedingly simple, consisting, as it did, in supplementing the fairly good table d'hôte luncheon with a basket of the most beautiful and delicious fruit. Such blushing velvet skinned peaches as these of the Blésois we have not seen, even in Tours, and the green plums of Queen Claude are equally delectable if not as decorative as the peaches. These, with great clusters of grapes, and a bottle of the white wine of Voudray, which Walter added to the mênu, made a feast for the gods to which Archie did ample justice. He looks handsomer than ever, and as brown as a Spaniard after the sea voyage. I am glad that we are by ourselves, agreeable as M. La Tour is, for as you know, Archie does not care much for strangers and our little family party is so pleasant. Archie's idea of enjoying a holiday is to motor from morning until night. We humored his fancy this afternoon and had a long motor tour, going through Montbazon and Couzieres, which we had not yet seen, although we were quite near both places at Loches. Our chauffeur, knowing by instinct that Lydia and I were of inquiring minds, told us that Queen Marie de Médicis came from Montbazon to Couzieres after her escape from Blois, and that here she and her son Louis were reconciled in the presence of a number of courtiers. This royal peacemaking we have always thought one of the most amusing of Rubens's great canvases at the Louvre, as he very cleverly gives the impression that neither the Queen nor her son is taking the matter seriously.

You will scarcely believe me, I fear, when I tell you that we only stopped at one château this afternoon. This was Archie's afternoon, you know, but the Château of Beauregard is so near that we simply could not pass it by, and the drive through the forest of Russy in which it stands was delightful. The château was closed to visitors, for which Archie said he was thankful, which rather shocked Lydia, who is as conscientious in her sightseeing as about everything else that she does. It was a disappointment to her and to me, as there is a wonderful collection of pictures there, an unbroken series, they tell us, including the great folk of fifteen reigns. Suddenly realizing our disappointment, Archie became quite contrite and did everything in his power to gain a sight of the treasures for us, but to no purpose, as the concierge was absolutely firm, even with the lure of silver before his eyes, and when he told us that the family was in residence we knew that it was quite hopeless to expect to enter. The Duchesse de Dino, whose interesting memoirs have been published lately, was the châtelaine of Beauregard in the early years of the last century.

We had a delightful afternoon, despite our disappointment about the château, and in the course of this ride Archie, who can understand almost no French, extracted more information from the chauffeur with regard to the soil, products, crops, and characteristics of Touraine than the rest of the party have learned in the ten days that we have spent here. These investigations were, of course, conducted by the aid of such willing interpreters as Lydia and myself.

"M. La Tour could tell you all about these things," said Lydia.

"And pray who is this M. La Tour that you are all quoting? Some Johnny Crapaud whom Zelphine has picked up, I suppose. She always had a fancy for foreigners."

"He is a very delightful person, and if you wait long enough you will see him," said Miss Cassandra, "as he has taken a great fancy to Walter."

"To Walter!" exclaimed Archie, and seeing the amused twinkle in Miss Cassandra's eyes he suddenly became quite silent and took no further interest in the scenery or in the products of Touraine, until Lydia directed his attention to the curious caves in the low hills that look like chalk cliffs. This white, chalky soil, M. La Tour had explained to us, is hard, much like the tufa used so much for building in Italy. We thought that these caves were only used for storing wine, but our chauffeur told us that most of those which are provided with a door and a window are used as dwelling houses, and they were, he assured us, quite comfortable. These underground dwellings, burrowed out like rabbits' warrens, with earth floors, no ventilation except a chimney cut in the tufa roof to let the smoke out, and only the one window and door in the front to admit light and air, seem utterly cheerless and uncomfortable, despite our chauffeur's assurances that they have many advantages. From the eloquence with which he expatiated upon the even temperature of these caves, which he told us were warm in winter and cool in summer, we conclude that he has lived in one of them, and are thankful that he could not understand our invidious remarks about them, for as Archie remarks, even a troglodyte may have some pride about his home.

Hôtel de France, September 10th.

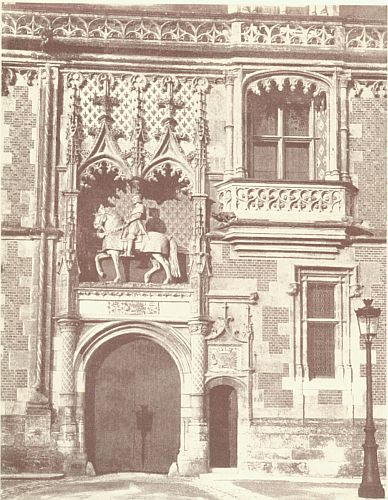

Neurdein Freres, Photo.

Entrance to Château of Blois with Statue of Louis XII

It is so delightful to be lodged so near the beautiful Château of Blois that we can see the façade of Francis I by sunlight, twilight, and moonlight. Built upon massive supporting walls, it dominates a natural terrace, which rises above the valley of the Loire and the ravine of the Arroux. No more fitting site could be found for the château than the quadrilateral formed by these two streams. The wing of Francis I, with its noble columns, Italian loggie, balustrades, attics, picturesque chimneys, grotesque gargoyles and other rich and varied decorations, displays all the architectural luxury of the Renaissance of which it was in a sense the final expression. It was while gazing upon this marvelous façade that Mr. Henry James longed for such brilliant pictures as the figures of Francis I, Diane de Poitiers, or even of Henry III, to fill the empty frames made by the deep recesses of the beautifully proportioned windows. We would cheerfully omit the weak and effeminate Henry from the novelist's group, but we would be tempted to add thereto such interesting contemporary figures as the King of Navarre and his heroic mother, Jeanne d'Albret, or his beautiful, faithless wife, La Reine Margot, the Pasithée of Ronsard's verse, who, with her brilliant eyes and flashing wit, is said to have surpassed in charm all the members of her mother's famous "escadron volant." And, as Miss Cassandra suggests, it would be amusing to see the portly widow of Henry IV descending from one of the windows, as she is said to have done, by a rope ladder and all the paraphernalia of a romantic elopement, although, as it happened, she was only escaping from a prison that her son had thought quite secure. The poor Queen had great difficulty in getting through the window, but finally succeeded and reached the ditch of the castle; friends were waiting near by to receive her with a coach which bore her away to freedom at Loches or Amboise, I forget which. This window from which Marie de Médicis is said to have escaped is in one of the apartments of Catherine. The guide, a very talkative little woman, told us that there is good reason to believe that the stout Queen never performed this feat of high and lofty tumbling; but that she made her escape from a window in the south side, and with comparative ease, as in her day there were no high parapets such as those that now surround the château on three sides. Our cicerone seemed, however, to have no doubts about the unpleasing associations with Catherine de Médicis, and took great pleasure in showing us her cabinet de travail, with the small secret closets in the carved panels of the wall in which she is said to have kept her poisons. These rooms are richly decorated, the gilt insignia upon a ground of brown and green being a part of the original frescoes. The oratory, of which Catherine certainly stood in need, is especially handsome and elaborate.

Even more thrilling than the poison closets are the secret staircase and the oubliette near by, into which last were thrown, as our guide naïvely explained, "tous ceux qui la gênait." Cardinal Lorraine is said to have gone by this grewsome, subterranean passage. Not having had enough of horrors in the rooms of the dreadful Catherine, we were ushered, by our voluble guide, into those of her son, Henry III. In order to make the terrible story of the murder of the Duke of Guise quite realistic, we were first taken to the great council chamber, before one of whose beautiful chimney places Le Balfré stood warming himself, for the night was cold, eating plums and jesting with his courtiers, when he was summoned to attend the King. Henry, with his cut-throats at hand, was awaiting his cousin in his cabinet de travail, at the end of his apartments. As the Duke entered the King's chamber he was struck down by one and then by another of the concealed assassins. Henry, miserable creature that he was, came out into his bedroom where the Duke lay, and spurning with his foot the dead or dying man, exclaimed over his great size, as if he had been some huge animal lying prone before him.

"It seems as if the victims of Amboise were in a measure avenged; the Dukes of Guise, father and son, met with the same sad fate, and at the time of the assassination of Le Balfré Queen Catherine lay dying in the room below." This from Lydia, in a voice so impressive and tragic that Archie turned suddenly, and looking first at her and then at me, said: "Well, you women are quite beyond me! You are both overflowing with the milk of human kindness, you would walk a mile any day of the year to help some poor creature out of a hole, and yet you stand here and gloat over a murder as horrible as that of the Duke of Guise."

"We are not gloating over it," said Lydia, "and if you had been at Amboise and had seen, as we did, the place where the Duke of Guise and the Cardinal, his brother, had hundreds of Huguenots deliberately murdered, you would have small pity for any of his name, except for the Duchess of Guise, who protested against the slaughter of the Huguenots and said that misfortune would surely follow those who had planned it, which prediction you see was fulfilled by the assassination of her husband and her son."

"That may be all quite true, as you say, dear Miss Mott; but I didn't come here to be feasted on horrors. I can get quite enough of them in the newspapers at home, and it isn't good for you and Zelphine either. You both look quite pale; let us leave these rooms that reek with blood and crime and find something more cheerful to occupy us."

The first more cheerful object which we were called upon to admire was the handsome salle d'honneur, with its rich wall decorations copied after old tapestries; but just a trifle too bright in color to harmonize with the rest of the old castle. In this room is an elaborately decorated mantel, called la cheminée aux anges, which bears the initials L and A on each side of the porc-épic, bristling emblem of the twelfth Louis, who was himself less bristling and more humane than most of his royal brothers. Above the mantel shelf two lovely angels bear aloft the crown of France, which surmounts the shield emblazoned with the fleur-de-lis of Louis and the ermine tails of Anne, the whole mantel commemorative of that most important alliance between France and Bretagne, of which we have heard so much. The guide repeated the story of the marriage, Lydia translating her rapid French for Archie's benefit.

Observing our apparent interest in Queen Anne, our guide led us out into the grounds and showed us her pavilion and the little terrace called La Perche aux Bretons, where the Queen's Breton guards stood while she was at mass. She is said to have always noticed them on her return from the chapel, when she was wont to say, "See my Bretons, there on the terrace, who are waiting for me." Always more Breton at heart than French, Anne loved everything connected with her native land. This trait the guide, being a French woman, evidently resented and said she had little love for Anne. When we translated her remarks to Miss Cassandra she stoutly defended the Queen, saying that it was natural to love your own country best, adding that for her part she was "glad that Anne had a will of her own, so few women had in those days; and notwithstanding the meek expression of her little dough face in her portraits, she seemed to have been a match for lovers and husbands, and this at a time when lovers were quite as difficult to deal with as husbands."

Walter, who says that he has heard more than enough of Anne and her virtues, insists that she set a very bad example to French wives of that time, as she gave no end of trouble to her husband, the good King Louis.

"Good King Louis, indeed!" exclaimed Miss Cassandra. "He may have remitted the taxes, as Mr. La Tour says; but he did a very wicked thing when he imprisoned the Duke of Milan at Loches. He and Anne were both spending Christmas there at the time, and we are not even told that the King sent his royal prisoner a plum pudding for his Christmas dinner."

"It would probably have killed him if he had," said Archie; "plum pudding without exercise is a rather dangerous experiment. Don't you think so yourself, Miss Cassandra?"

"He might have liked the attention, anyhow," persisted the valiant lady, "but Louis seems to have had an inveterate dislike for the Duke of Milan, and Mr. La Tour says that one of his small revenges was to call the unfortunate Duke 'Monsieur Ludovico,' which was certainly not a handsome way to treat a royal prisoner."

"No, certainly not," Walter admitted, adding, "but from what we have seen of the prisons of France, handsome treatment does not seem to have been a marked feature of prison life at that time; and Anne herself was not particularly gentle in her dealings with her captives."

Probably with a view to putting an end to this discussion, which was unprofitable to her, as she could not understand a word of it, the guide led us back to the château and showed us the room in which Queen Anne died. Whatever may have been her faults and irregularities of temper, Anne seems to have had a strong sense of duty and was the first Queen of France who invited to her court a group of young girls of noble family, whom she educated and treated like her own daughters. She even arranged the marriages of these girls entirely to suit herself, of course, and without the slightest regard to their individual preferences, which was more than she was able to do in the case of the young princesses, her children. She lived and died adored by her husband, who gave her a funeral of unprecedented magnificence, and although Louis soon married again, for reasons of state, he never ceased to mourn his Bretonne whom he had loved, honored, and in many instances obeyed.

Anne's insignia of the twisted rope and the ermine tails are to be found in nearly every room in the château, and here also is the emblem of her daughter, a cygnet pierced by an arrow, which seems symbolic of the life of the gentle Claude of France, whose heart must often have been wounded by the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, as she was made to feel keenly, from her wedding day, that the King, her husband, had no love for her.

Matrimonial infelicities are so thickly dotted over the pages of French history that it is impossible to pause in our excursions through these palaces to weep over the sorrows of noble ladies. Indeed, for a French king to have had any affection for his lawful wife seems to have been so exceptional that it was much more commented upon than the unhappiness of royal marriages. These reflections are Miss Cassandra's, not mine; and she added, "I am sorry, though, that Anne's daughter was not happy in her marriage," in very much the same tone that she would have commented upon the marriage of a neighbor's daughter. "I hope the beautiful garden that we have been hearing about was a comfort to her, and there must be some satisfaction, after all, in being a queen and living in a palace as handsome as this." With this extremely worldly remark on the part of our Quaker lady, we passed into the picture gallery of the château, where we saw a number of interesting portraits, among them those of Louis XIII and of his son Louis XIV, in their childhood, quaint little figures with rich gowns reaching to their feet, and with sweet, baby faces of indescribable charm. Here also is a superb portrait of Gaston, the brother of Louis XIII, and a portrait bust of Madame de Sévigné, whose charming face seems to belong to Blois, although she has said little about this château in her letters. Here also are portraits of Madame de Pompadour, Vigée Lebrun, as beautiful as any of the court beauties whom she painted, and a charming head of Mademoiselle de Blois, the daughter of Louise de La Vallière, whom Madame de Sévigné called "the good little princess who is so tender and so pretty that one could eat her." This was at the time of her marriage, which Louis XIV arranged with the Prince de Conti, having always some conscience with regard to his numerous and somewhat heterogeneous progeny.

And in this far off gallery of France our patriotism was suddenly aroused to Fourth of July temperature by seeing a portrait of Washington. This portrait, by Peale or Trumbull, was doubtless presented to one of the French officers who were with Washington in many of his campaigns, and the strong calm face seemed, in a way, to dominate these gay and gorgeously appareled French people, as in life he dominated every circle that he entered.

We were especially interested in a bust of Ronsard with his emblem of three fishes, which delighted Walter and Archie, who now propose a fishing trip to his Château of La Poissonnière. We love Ronsard for many of his verses, above all for the lines in which he reveals his feeling for the beauties of nature, which was rare in those artificial days. Do you remember what he said about having a tree planted over his grave?

"Give me no marble coldWhen I am dead,But o'er my lowly bedMay a tree its green leaves unfold."XI

THE ROMANCE OF BLOIS

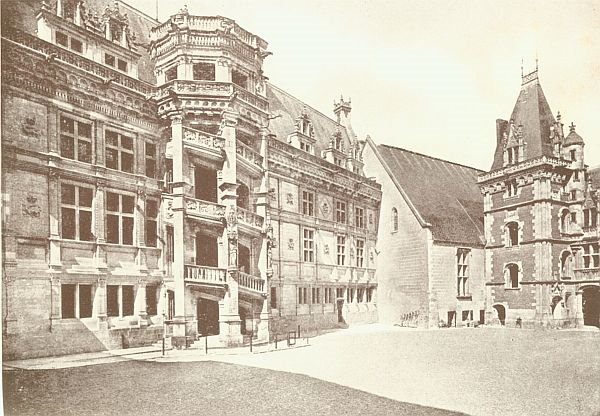

Hôtel de France, Saturday afternoon.Walter and Archie have elected to spend a part of this afternoon in the Daniel Dupuis Museum, over whose treasures, in the form of engraved medals, they are quite enthusiastic. We women folk, left to our own devices, wandered at will through the first floor rooms and halls of the Château of Blois. The great Salle des Etats, with its blue ceiling dotted over with fleur-de-lis, is said to be the most ancient of them all. Beautiful as many of the rooms are, despite their somewhat too pronounced and vividly colored decorations, and interesting as we found the remains of the Tour de Foix upon which tradition placed the observatory dedicated by Catherine and her pet demon, Ruggieri, to Uranus, the crowning glory of the Château of Blois is the great Court of Honor. We never pass through this impressive portal, surmounted by the gilded equestrian figure of Louis XII, without a feeling of joy in the spaciousness and beauty of this wide sunny court. At a first glance we were bewildered by its varied and somewhat incongruous architecture, the wing of Louis XII, with its fine, open gallery; that of Charles d'Orléans, with its richly decorative sculpture; the Chapel of St. Calais, and the modern and less beautiful wing of Gaston, the work of Francis Mansard, but after all, and above all, what one carries away from the court of Blois is that one perfect jewel of Renaissance skill and taste, the great staircase of Francis I. An open octagonal tower is this staircase, with great rampant bays, delicately carved galleries and exquisite sculptured decorations. Indeed, no words can fully describe the richness and dignity of this unique structure, for which Francis I has the credit, although much of its beauty is said to have been inspired by Queen Claude.

We all agreed that this staircase alone would be worth while coming to Blois to see, with its balustrades and lovely pilasters surmounted by Jean Goujon's adorable figures representing Faith, Hope, Abundance, and other blessings of heaven and earth. The charming faces of these statues are said to have been modeled after Diane de Poitiers and other famous beauties of the time. While wandering through the court, we came suddenly upon traces of Charles of Orleans, who was taken prisoner at the battle of Agincourt, and was a captive for twenty-five years in English prisons. A gallery running at right angles to the wing of Louis XII is named after the Duke of Orleans, probably by his son Louis. This gallery, much simpler than the buildings surrounding it, is also rich in sculpture and still richer in associations with the poet-prince, who is said to have solaced the weary hours of his imprisonment by writing verses, chansons, rondeaux, and ballades, some of which were doubtless composed in this gallery after his return from exile. The lines of that exquisite poem, "The fairest thing in mortal eyes," occurred to Lydia's mind and mine at the same moment. We were standing near the ruins of an old fountain, looking up at the gallery of Charles of Orleans and repeating the verses in concert like two school girls, when Miss Cassandra, who had been lingering by the staircase, joined us, evidently not without some anxiety lest we had suddenly taken leave of our senses. Finding that we were only reciting poetry, she expressed great satisfaction that we did not have it in the original, as she is so tired of trying to guess at what people are talking about.

Court of Blois with Staircase of Francis I

Indeed, Henry Cary's translation is so beautiful that we scarcely miss the charm of the old French. We wondered, as we lingered over the lines, which one of the several wives of the Duke of Orleans was "the fairest thing in mortal eyes,"—his first wife, Isabelle of France, or Bonne d'Armagnac, his second spouse? His third wife, Marie de Cleves, probably survived him, and so it could not have been for her that there was spread a tomb

"Of gold and sapphires blue:The gold doth show her blessedness,The sapphires mark her true;For blessedness and truth in herWere livelily portrayed,When gracious God with both his handsHer goodly substance made.He framed her in such wondrous wise,She was, to speak without disguise,The fairest thing in mortal eyes."It was pleasant to think of the poet-prince spending the last days of his life in this beautiful château with his wife, Marie de Cleves, and to know that he had the pleasure of holding in his arms his little son and heir, Louis of Orleans, afterwards the good King Louis, our old friend, and the bone of Walter's contention with Miss Cassandra.

By the way, I do not at all agree with that usually wise and just lady in her estimate of Louis XII. As M. La Tour says, he was far in advance of his age in his breadth of mind and his sense of the duty owed by a king to his people. Perhaps something of his father's poet vision entered into the more practical nature of Louis, and in nothing did he show more plainly the generosity and breadth of his character than in his forgiveness of those who had slighted and injured him,—when he said, upon ascending the throne, "The King of France does not avenge the wrongs of the Duke of Orleans," Louis placed himself many centuries in advance of the revengeful and rapacious age in which he lived.

Another poet whose name is associated with Blois is François Villon. A loafer and a vagabond he was, and a thief he may have been, yet by reason of his genius and for the beauty of his song this troubadour was welcomed to the literary court of Charles d'Orléans. That Villon received substantial assistance and protection from his royal brother poet appears from his poems. Among them we find one upon the birth of the Duke's daughter Mary: Le Dit de la Naissance Marie, which, like his patron's verses, is part in French and part in Latin.

In this château, which is so filled with history and romance, our thoughts turned from the times of Charles of Orleans to a later period when Catherine sought to dazzle the eyes of Jeanne d'Albret by a series of fêtes and pageants at Blois that would have been quite impossible in her simpler court of Navarre. The Huguenot Queen, as it happened, was not at all bedazzled by the splendors of the French court, but with the keen vision that belonged to her saw, through the powder, paint, tinsel, and false flattery, the depravity and corruption of the life that surrounded her. To her son she wrote that his fiancée was beautiful, witty, and graceful, with a fine figure which was much too tightly laced and a good complexion which was in danger of being ruined by the paint and powder spread over it. With regard to the marriage contract which she had come to sign, the Queen said that she was shamefully used and that her patience was taxed beyond that of Griselda. After many delays the marriage contract was finally signed, and a few days later the good Queen of Navarre was dead, whether from natural causes or from some of the products of Queen Catherine's secret cupboards the world will never know, as Ruggieri and Le Maître were both at hand to do the will of their royal mistress with consummate skill, and to cover over their tracks with equal adroitness.