полная версия

полная версияThe Legend of Sir Lancelot du Lac

The black and white knights are treated by D. L. as purely visionary and symbolic, and no names are given.

The incident of the black knight, who issues from the lake and kills Lancelot's horse, differs in 1533 from the other four versions. Instead of striking the horse at once he rides past Lancelot without touching him, then returns, striking the horse en route and disappearing in the lake. I suspect that this is the right version; the knight is evidently a water-demon, and having his dwelling in the lake should return there.

At the commencement of Book XVI., when Gawain and Hector meet, they ask if any tidings have been heard of the principal questers. Here there are some interesting variants: Q. mentions Lancelot, Galahad, and Bohort, but says these four are the best of the questers; D. L. only mentions these, but says rightly these three; 1533 first mentions Lancelot alone, then Galahad, Perceval, and Bohort, and reckoning all together, says these four, and with this M. and W. agree.

There are but few interesting variants in the account of Bohort's adventures; the symbolic interpretations are, as usual, much less insisted upon, indeed 1533 gives no such explanation either of the disinherited lady, or of the 'lily and dry wood' vision, though Bohort is assured of Lionel's safety. The fight between the two brothers is also more briefly told: we do not hear that they lie long unconscious after the flame descends, but Bohort is told at once to join Perceval. Here W. agrees with D. L. and 1533.

D. L. differs from all the other versions in naming the damsel who warns Bohort of her mistress' suicidal intention. She is called Pallada.

In Book XVII., in all concerning the mysterious ship, the text of D. L. and 1533 is far superior to that of Q. The inscription in D. L. runs thus:

'Hort man, die wils gaen hier in,Besie di wel, ende oec mercDattu sijs geloves vol ende sterc.Want ic els niet dan gelove benHier bi hoede elkerlijc hem:Falgiert hem eneger manirenVan gelove, ic sal hem falgiren.'—ll. 7910-16.1533 says the inscription is in 'langaige dit Caldeu,' and says 'si tost q tu guerpiras ta creance ie te guerpiray en telle maniere que tu ne auras de moi ne conseil ne ayde,' and proceeds to explain (which no other text I have consulted does) that if he who enters fail in faith he will fall into the water. This should be compared with the passage in Hucher,183 where the inscription on the ship agrees closely and is also said to be in Caldiu. The warning as to the nature of the penalty is omitted here, but the penalty is incurred exactly as 1533 foretells.

M. evidently had the warning of D. L. and 1533 before him when he wrote 'for and thou faile I shal not helpe the /.' W. gives the warning in more general terms, due perhaps to the translator.

Perceval's speech on entering the ship is again best given by 1533. Here, he says, he will enter 'pour ce que se ie suis desloyal que ie y perisse comme desloyal, et se ie suis plain de foy et tel comme bon chevalier doit estre que ie soye sauvé,' i.e. he submits to the test in all humility. Q. says: 'Car iou sui plain de foi et teus comme chivalers doit estre,' thus omitting the qualifying phrases, and giving the speech quite a different meaning. W. closely agrees with Q. D. L. also, though less abrupt, practically agrees with Q.; while M. must have had the version of 1533 before him: 'for yf I be a nys creature or an untrue knyghte there shalle I perysshe'—a reading he could not possibly have derived from either of the other two.

In the account of the scabbard of the sword we have a most interesting variety of readings, but, comparing one with the other, it appears certain that here again 1533 is in the right.

One side of the scabbard is said by D. L., 1533 and M. to be red as blood, with an inscription in letters black as a coal; while Q. says the scabbard is 'black as pitch'—an evident confusion with the inscription. W. says the sheath is 'rose-red,' with letters of gold and silver.

The name is given differently in each instance: Q., memoire de sens; D. L., Gedinkenesse van sinne; M., meuer of blood; 1533, memoire de sang. D. L. and 1533 go on to say that 'none shall look upon that part of the scabbard which is made of the Tree of Life but they shall be reminded of the blood of Abel.' M. omits the latter part of this sentence, thus making great confusion.

Now, comparing these versions together, the right reading becomes perfectly clear. The scabbard is red, for it was made (at least one half of it was) of the wood of the Tree of Life, which, as we are distinctly told, turned red at the death of Abel; and the inscription 'memoire de sang' was intended to keep this event in mind. The confusion, in the case of Q. and D. L., clearly arose from the MS. at the root of the first having had the reading sans for sanc or sang (a reading often met with); a careless copyist, heedless of the sense of his transcription, wrote sens and this was correctly translated by the compiler of D. L. as sinne; a reading which, however unintelligible in itself, would probably not strike the compiler (who was certainly an intelligent writer with a very good knowledge of French) as absolute nonsense, inasmuch as it was connected with the 'calling to mind' of the death of Abel. Q., who omits this qualifying passage, does make nonsense of it. In M.'s case the mistake was in the first word, and probably arose from a confusion between m and uv, which may very well be due to Caxton; otherwise M. appears to have had the same version as 1533, which, alone, has preserved it free from error. W. omits the inscription altogether.

The 'erle Hernox' in M., Ernous in Q., is in D. L. and 1533 Arnout and Arnoul. Ernoulf in W.

Both D. L. and 1533 state that the maiden who shall cure the lady by her blood must be not only a virgin and a king's daughter but Perceval's sister. This is neither in Q. nor in M., and may perhaps indicate that, as I have suggested, these two versions belonged to an original Perceval-Lancelot redaction, from which they introduced occasional additions to Perceval's share of the Queste, as in the previous allusion to his having recovered his kingdom in D. L.184

In the account of Lancelot's visit to Corbenic, after being struck down at the sight of the Grail, Q. says he is discovered seated (seant) before the door, while the other three all represent him as lying (lyinge—licgende—gisant), which is certainly more in harmony with the general situation. D. L. says that when Lancelot recovers and knows he has lain unconscious fourteen days he bethinks him:

'Hoe hi hadde gedient den viant.xiiij. jaer, ende pensede te hant,Dat hem onse here daerti dedeDie macht verlisen in sine lede.xiiij. dage.'—ll. 9919-23.Whereas Q. only says 'qu'il avoit servi l'anemi.' A meaningless phrase, as it stands. M. agrees with D. L. with the exception that he says twenty-four instead of fourteen, in which he is certainly correct, as Lancelot's liaison with Guinevere had begun long before the birth of Galahad. The number may have been altered by the compiler of D. L. for the exigencies of the rhyme, which would not admit the original form. 1533 omits the passage altogether, condensing considerably at this point.185 W. does not specify whether he were lying or seated, but agrees with D. L. in giving fourteen years, which rather looks as if that number may have been in the source of this latter.

In the account of the questers at Castle Corbenic D. L. and 1533 alike clear up a passage which, as it stands, is obscure in M. and utterly unintelligible in Q. Nine stranger knights arrive at the castle,186 three being of Gaul, three of Ireland, and three of Denmark. When they separate the next day, Q. has this unintelligible passage—Galahad has asked the strangers' names—'et tant qu'il trouverent estrois de gariles, que claudins li fieus le roi claudas, en ert li uns et li autre de quel terre qu'il fuissent, erent asses gentile homme et de haut lignage.'187 M. renders, without any mention of names being asked, 'But the thre knyghtes of Gaule, one of them hyghte Claudyne, kynge Claudas sone / and the other two were grete gentylmen' (which should surely have given Dr. Sommer a clue to the right rendering of the passage).

D. L. runs thus:

'Ende alsi buten den castele quamenVragede elc oms sanders namen,Soedat si worden geware das,Dat van den drien van Gaule wasClaudijn Claudas sone die een,Ende si vonden van den anderen tweenDat si waren van groter machteRidders, ende van groten geslachte'—ll. 10601-8.1533 has, 'Si trouverent que des trois de Gaulle Claudius le filz au roy Claudas en estoit ung et les autres estoiet assez vaillans.' It seems clear that M.'s text is that of D. L. carelessly abridged.188

Both D. L. and 1533 conclude the Queste section with the passage relating the death of the twenty-two (twenty-four) questers, eighteen of whom fell by the hand of Gawain; the writing out of the knights' adventures, and the preservation of the record in the abbey of Salisbury where Map found them, this latter item being omitted by 1533. This passage is, as a rule, now found at the beginning of the Mort Artur section, but, I think, it is clear that its proper place is at the end of the Queste; as I have pointed out already, the light in which it represents Gawain is entirely in keeping with that romance, while it does not agree with either the Mort Artur or the Lancelot, both of which regard Arthur's gallant nephew with genuine respect. Further, the drawing up of a record of adventures is better placed at the end of the section dealing with the adventures to be recorded than at the beginning of another. M.'s words, 'alle this was made in grete bookes / and put up in almeryes at Salysbury /' coupled with his total omission of any corresponding passage at the commencement of the next book, seem to prove that in his source, too, it stood at the end of the Queste.189

What now are the results we may deduce from this examination of four versions of the Galahad Queste? First, I think it is clear that the verse translation in D. L. and the prose 1533 both offer a text very decidedly superior to that edited by Dr. Furnivall, and, if Dr. Sommer's extracts are to be relied on, that represented by the majority of the printed editions of the Lancelot. Second, it is equally clear that the text used by Malory stood in close relation to these two versions. Many variants attributed by Dr. Sommer to the English compiler, are, it is now certain, due to his source, in the treatment of which he shows little sign of intelligence or invention, but rather a tendency to compression at all hazards, sometimes omitting the very part of a phrase which was required to make the whole intelligible. The general tendency of our examination, therefore, goes to establish the practical agreement of D. L., 1533 and M., as against Q. and S. The version given by W. is so free a rendering, and omits so many details, that it is scarcely possible to place it. It seems clear that the original source must have belonged to the same MS. family as the former three, but whether the agreement was with 1533, rather than with D. L. and M., or vice versa, it is impossible to say.

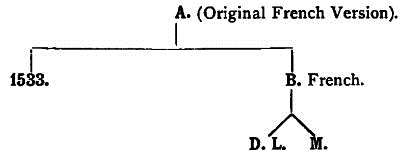

But how do these three stand as regards each other? On the whole 1533 appears to represent the better text, and it also appears to have preserved signs of an earlier redaction, yet I do not think it is the direct source of the other two. We often find D. L. and M. agreeing in details of numbers and names, as against the other version; certainly in the case of such a name as Brimol van Pleîche, Bromel la Pleche, the agreement must be due to a French source common to both. I should be inclined to postulate some such scheme as this.

As will be seen from the summary of D. L. appended to these studies, both this version and M. show, in the Lancelot section, a certain plus of incident as against 1533, though these incidents vary in each case. The relation cannot, therefore, be exactly determined, but I think there can be no reasonable doubt that for the Lancelot-Queste section of his compilation Malory used an Agravain-Queste MS.

That he had two MSS., one for the Lancelot, another for the Queste, as Dr. Sommer190 suggests, is highly unlikely. It would be too curious a chance that he should in each case hit on a version so closely corresponding to that of the two with which we have compared his reading.

This appears to me practically to dispose of the argument, that Malory had before him a number of episodic romances, an argument often brought forward;191 the 'Turquine' episode in Book VI., the whole of Book VII., and the adventure with the damsel of Escalot being instances in point. Turquine certainly came out of the Lancelot, as did the lady of Escalot; Book VII. may have been an episodic romance, as also the handling of Urre of Hungary; though this latter, as we shall see, may equally well be an amplification of an adventure found in the prose Lancelot.192

Again, it very greatly limits the probability of Malory's having elsewhere worked with a free hand, inventing and rearranging, when we find, as we have done, that numerous small details, hitherto ascribed to him, are faithful reproductions of his source. We are justified in cherishing very serious doubts as to the originality of any marked deviation from the traditional version of an adventure which we may find in his compilation.

These arguments, of course, apply most strongly to his version of the Charrette adventure, the problem of source of which, so far as Malory is concerned, is absolutely unaffected by the evidence we have collected. This alone is certain, there is no proof whatever that he knew anything of the first part of the Lancelot romance, his treatment of the Lady of the Lake seems to show that he was absolutely ignorant of it. He was not in the habit of departing unnecessarily from his source, his variations as a rule are slight, and their motive can generally be detected; when, therefore, we find him giving an entirely different account of the abduction of Guinevere from that given elsewhere, the probabilities are all in favour of his reproducing a separate source, and all against his original invention. So far as the matter stands in the light of the latest evidence, the question remains unsolved, with a decided balance in favour of the theory advanced by M. Gaston Paris, and against that advocated by Professor Foerster.193

Leaving the question of Malory, what may we hold to be the result of this examination on the problem of the Queste itself? Is the form in which we possess it practically the original form, or are we to postulate a series of successive redactions? I think that every one who has carefully studied the variants given above must have been struck by the fact that in no case is the question one involving a variety of incident or even an alteration in sequence. It is the same story in every case, told in the same order, in the same words, only certain copies give a fuller and more coherent version than others. In fact, as I said above, the variations are the variations of the copyist, not of the compiler. The one point in which we may postulate either omission or addition, i.e. the greater or less fulness, the presence or absence, of the 'improving' sections, is precisely a point in which we might expect a copyist of a more or less didactic turn of mind to assert himself; it was so easy to expand or to contract such passages. And it is a curious feature that precisely in those versions in which the story, as a whole, is the best told (D. L., 1533, and in a minor degree M.), we find the edifying passages in their shortest forms; while Q., the text of which as compared with the others is decidedly poor, gives them at the greatest length.

Of any previous redaction of Galahad's adventures there is no trace; there are no lengthy interpolations as in the Conte del Graal MSS.; there is no conflict, such as we find in other romances, between an earlier and later form; in sundry passages we have allusions to unrelated adventures: we are told that the heroes ride so many days, weeks, or years, and meet with many and strange adventures, but in no copy do we find any hint of what these adventures may have been; yet had there existed an earlier and fuller form, some fragments of it must surely have been preserved.

And this argument becomes more convincing the more closely we look into it. Above we have compared four versions of the Queste (five if we include W.), but one of these, Dr. Furnivall's edition, does not represent one ms. only, but is founded on a critical collation of two, and contains a specimen of the opening columns of twelve mss. of the Bibliothèque Nationale; while Dr. Sommer states that he has examined four other versions and found that, saving details of style, all agree in incident and sequence. We may therefore take it as certain that one of the four variants represents at least five MSS., while scholars of standing assure us of the practical identity of sixteen more!

Now, side by side with these Queste versions, we have compared four versions of the prose Lancelot, and of these four no two agree perfectly throughout, and all differ from the summary given by M. Paulin Paris.

D. L. and 1533, which on the whole correspond well with each other, yet have their distinctive differences, i.e. D. L. contains adventures not related by 1533; M., while on one side condensing arbitrarily, on the other gives two adventures known to neither of the first; and S. omits an important section altogether. The summary in Romans de la Table Ronde, while agreeing on the whole with the two first, deviates from both in the later sections.194

The practical identity of all the versions of a romance transmitted in so large a number of MSS. as the Queste is, I believe, unique in the Arthurian cycle. Such a phenomenon, for it is nothing less, can, I think, only be explained in one way: there was but one version of the story, and that version took shape, not at a period when oral transmission was the rule, but at a later date, when the story could at once find expression in literary form. I do not believe that any story, the earlier stages of which were developed orally, is ever, when committed to writing, found so entirely free from variants.195

Can we decide what special form of the Perceval Queste the Galahad variant was intended to supersede? I think not: it is noticeable that the writer never gives any adventure which finds an exact parallel in the older romances, yet he not only knew the Perceval story, but knew it in various forms. The allusions in Book XIV., though slight, are remarkably instructive: he knew that Perceval was the son of a widow, and that his mother died of grief at his departure (Chrétien, Wolfram, Didot Perceval); that in his wanderings in search of the Grail he came to the dwelling of a female recluse, who proved to be a near relative (only related by Wolfram); that he has a sister (Didot Perceval, and Perceval li Gallois). Thus in these few allusions he is in touch with the whole cycle of Perceval romance! When, therefore, we find that he never elsewhere assigns to Perceval any of the adventures traditionally connected with him, but gives him a new series which are duplicated elsewhere, one can only conclude that it is done of set purpose.

Of the parallels given above, the existence of the sister appears to me to be the most important, judging from the prominence of the rôle here assigned to her. She only appears in the two forms of the Perceval Queste which show traces of having formed part of a cycle; and inasmuch as Perceval li Gallois represents the mother as living to see her son return, and regain his kingdom, the correspondence is closer with the Didot Perceval, but the question can hardly be settled.

As a Grail romance the Queste is extremely poor. The utter confusion of the writer as to the identity of the Fisher King and Maimed King; the inter-relation of Grail Winner, owner of Grail Castle, Fisher King and Maimed King; the neglect of the most obvious conditions of the quest, such as ignorance on the part of the predestined Grail Winner; his giving proof of identity by fulfilment of a test; the inaccessibility of the Grail castle to all but the elect knight—all show a most extraordinary carelessness on his part, were he intending to write a Grail romance pure and simple. Ignorance we cannot postulate. He knows too much about Perceval not to know more about the Grail! It is evident throughout that the main anxiety of the author is to keep himself in touch with the Lancelot rather than with the Grail tradition. He is extremely careful to introduce references to that portion of the Lancelot story with which he is familiar; to explain that the adventures foreshadowed in Grand S. Graal and Lancelot have been really fulfilled, and so long as he can demonstrate his hero to be a worthy upholder of the glories of the race of King Ban, he cares very little if he fails to fulfil the necessary conditions of the original Grail Winner. This latter may know from the first what the Grail is, where it is, his own predestined relation to it, his final winning it may be reduced to an absurdity by the presence of eleven or twelve others all equally worthy of beholding the sacred talisman, but that matters nothing to the author; he has contrived to bring the Grail into more or less harmony with the Lancelot legend; he has crowned the most popular of Arthur's knights with reflected glory as father of the Grail Winner, he has put the last touch to the evolution of the Lancelot legend, and in so doing he has achieved the task which he set himself to perform. The Queste is in all essential features not a Grail but a Lancelot romance, and as such primarily it should be judged.