полная версия

полная версияThe Legend of Sir Lancelot du Lac

In the account of Perceval's being driven from court by the mockery of Kay and Mordred, D. L. has a remark which again shows the influence of an earlier tradition: Perceval is described as 'Eene harde jonge creature, ende die wel simpel sceen te dien.' Nowhere else is there any sign of the simplicity which is a primitive trait of Perceval's character. Later on, after the 'Patrides' adventure (which appears to be differently related from S. as it is from M., Patrides and the lady having fled together, been overtaken, and imprisoned), both 1533 and D. L. agree in the words spoken by Patrides (D. L.) or the king (1533), i.e. that Kay and Mordred have driven from court one who should be a better knight than all save Gawain.

'Ghi hebt entrouwen, dat secgic u,Uter herbergen verdreven nuDen besten ridder dier in wasSonder Walewein sijt seker das.'—ll. 36247-50.(1533 says 'When he is grown to manhood' he shall be as good, etc.) This certainly points to an earlier stage of tradition, when Perceval and Gawain are the leading knights and Lancelot subordinate to both.

In view of what we now know, I think it is not an unreasonable hypothesis that these two versions, which agree so closely, represent an earlier pseudo-Borron Lancelot-Perceval redaction, which has been worked over in the interest of the later pseudo-Map Galahad version.173

Book XII. M. gives the account of Lancelot's frenzy and subsequent cure. Here D. L. agrees with M. in saying that Lancelot strikes the shield as if X. knights did it, whereas both S. and 1533 give XII. Later on D. L. is alone against the other three in saying that Lancelot has only his ankles fettered, whereas the other three versions give ankles and wrists. Nevertheless here I think D. L. is right, as when Lancelot rushes after the boar both S. and 1533 agree in saying that he breaks the rings on his ankles, and make no mention of those on the wrist. Again D. L. makes no mention of hunters, the horse Lancelot takes he finds tied at the castle gate. As later on, when he comes up with the quarry no hunters are mentioned in any version, I think it probable that they were not in the original, but introduced later by some copyist to account for the boar.

At this point D. L. departs abruptly from the other versions, taking up the Perceval story. It is impossible to say whether this be due to a lacuna in the source, which the compiler filled up as he pleased, or whether this really represents an important (and apparently lost) Lancelot redaction. In the remainder of the incidents represented by this book 1533 agrees on the whole with S., with this important difference, that it makes it quite clear throughout that there is a period of some years involved. The reader quite understands all the details of Galahad's arrival at the abbey, his age, etc. Very probably the compiler of 1513 (Dr. Sommer's source) condensed here, as elsewhere, thus causing the confusion noted on p. 205 of the Studies.

CHAPTER X

THE QUESTE VERSIONSWe now reach a very important point in our investigation. The Lancelot section of Malory is not only so much condensed, but also so fragmentary in character, and, apparently, so capricious in choice of incident that a critical comparison between the version there offered and other forms of the Lancelot story can never be productive of a completely satisfactory result. It is one of those cases in which we must be content with probability, and renounce the hope of arriving at certainty. We have evidence enough to enable us to form an hypothesis as to the original character of the MS. used by Malory; of its actual condition, whether complete or incomplete, and, if the former, of the reasons which determined the compiler in his choice of incident, we cannot yet speak positively. I doubt if we shall ever be able to do so.

But with the Queste section it is different. As I remarked before, this part of the Lancelot cycle is far more homogeneous in structure than the sections preceding or following it: it is a romance within a romance, complete and rounded off in itself. Malory appears to have felt this; he condenses still, it is true, but it is condensation, not omission; he follows the sequence of incident accurately, begins with the beginning, ends with the end, consequently we are in a far better position for comparing his version with that of the other texts, and can hope to arrive at a really satisfactory result.

The first noticeable variant is in the passage 'for of a more worthyer mans hande may he not receive the order of knyghthode,' words spoken by the abbess to Lancelot. These are not in Q. but are in D. L.:

'Ende ic soude gerne sien dathiVan uwer hant ridder werde, wildi;Bedie van beteren man, sonder waen,En mocht i ridderscap niet ontfaen.'—Book III. 61-64.Also in 1533: 'car de plus preudhomme que de vous ne pourrait il recevoir l'ordre de chevalerie sicomme il nous est advis,' vol. iii. fo. 67. Here then M., D. L. and 1533 agree together against Q. W. has 'for we think that a better than he could not receive that dignity,' thus referring the phrase to Galahad—a probable misreading of the original French.

In the account of the arming of Galahad, omitted in M., Q. and D. L. agree in saying that Lancelot buckles on one spur, Bohort the other, whereas 1533 gives Lionel and Bohort. This latter is, I think, the right version, otherwise Lionel, though present, would have no share in the ceremony. W. also omits Lionel, and makes Bohort only bestow a kiss on the youth, Lancelot buckling on the spur, in this case one only.

In the adventure of the sword in the stone we again find M., D. L. and 1533 in accord against Q. All three relate that Gawain attempts to draw the sword and fails. This must be correct, as Q., though not saying that he makes the attempt, represents Arthur as telling him to laissies ester the moment he touches the hilt, words which both D. L. and 1533 place in Arthur's mouth after the attempt:

'Nu laet staenGi hebet wel min bevelen gedaen.'—ll. 231-2.This latter phrase is evidently represented by M.: 'I thanke yow ſaid the kynge to ſyre Gawayne /' W. records Gawain's (Gwalchmei's) attempt, but not the king's speech.

According to 1533 no other knight makes the attempt. D. L. records Perceval's failure, and says that after that none would essay the venture.

'Soe datmen vord daer niemanne vant,Die daer an wilde doen die hant.'—ll. 255-56.I suspect that M., 'Thenne were there moo that durſte be ſoo hardy to ſette theire handes thereto /,' should be corrected by the substitution or insertion of a negative (no before moo or none), it would read more coherently. W. relates no attempt after Perceval, but does not say definitely that no one essays the feat.

The result here is clearly, M., D. L., 1533 against Q., with special agreement of M. and D. L., 1533 and W.174

In the case of Galahad's message to his relations at Corbenic, every one of the versions gives a different rendering.

M. My graunt sir Kynge Pelles / and my lord Petchere / (a manifest error).

Q. Mon oncle le roi Pelles / mon aioul le riche pescheoure.

D. L. Min here den Coninc Pelles—enten Coninc Vischere min ouder vader.

1533. Mon oncle le roy pescheur—et mon aieul le roi Pelles.

The greeting is omitted in W.

It is difficult to know what to make of such confusion, but of the four variants I prefer the last as possessing a certain raison d'être. The Fisher King was certainly the uncle of the original Grail Winner, and King Pelles is as certainly the grandfather of Galahad. It looks to me as if the compiler of this version had made an effort to combine the Perceval and Galahad stories, though his version as it stands is in contradiction to his text.175

D. L. text should be noted as compared with the statement of the earlier section, that the Maimed King and Fisher King are one, and that the personage thus named is not King Pelles but his father. The manifest uncertainty of the Galahad Queste as to the identity of this personage, and his relationship to the Grail Winner, as compared with the much clearer statements of the early Perceval story appear to me a proof of the lateness of the former. As to which of the four versions given represents the real view of the author of the Queste, I should not like to hazard an opinion—probably copyists altered according to their own particular view of the matter!

After the appearance of the Grail there is an interesting passage, omitted in M., where Gawain remarks that each has been served with whatever food or drink he desired, which had never happened before save in the court of the roi mehaignet (Q.); roi Perles (1533, which generally adopts this spelling), coninc Vischer (D. L.). Here Q. stops, but D. L. and 1533 continue Gawain's speech, nom-pourtant ils ne peuvent onques veoir le sainct vaisseau ainsi comme nous l'avons veu, ainsi leur a este la semblance couverte (vol. iii. fo. 69). Maer si waren bedrogen in dien, Dat sijt niet oppenbare mochten sien (687-8). Nevertheless, since he has not seen it as clearly as he might, he will go in quest till it be wholly revealed to him. I think the above passage is the source of M. '/ one thynge begyled vs we myght not ſee the holy Grayle / it was ſoo precyouſly couered /.' The compiler omits, as I said above, Gawain's reference to the previous appearance, but adapts the latter part of his speech to the circumstances he is narrating. W. gives the passage practically in its entirety, but so freely rendered that we cannot use it for textual comparison. The king is called King Peleur.

Here again I think we may postulate an agreement between M., D. L., 1533 and W. in a feature omitted by Q.176

D. L. is alone against the other three in not giving the owner of the castle 'Vagan' the same name as his castle, but simply says: 'Nu was een goet man te Vagan' (l. 1146), which I suspect is the right version. W., on the contrary, does not name the castle, but says it belonged to Bagan, 'a good and religious man.'

In the account of the adventure with the shield, both D. L. and 1533 give Galahad's remarks to his companions more fully than do Q. or M., though the general bearing of the passage is well represented in this latter. In both the first Galahad tells his companions that if they fail in the adventure then he will attempt it; 1533, 'et se vous ne le pouez emporter ie l'emporteray, aussi n'ay ie point d'escu'; they then offer to leave him the adventure, but he tells them they must essay it first. D. L.:

'Elst nu dat gi falgiert daer an,Ic sal daventure proven dan—In' brachte genen scilt met mi.'—ll. 1244-54.With this W. agrees.

Here, again, D. L., 1533, and W. give a much clearer text than Q.; and M., though condensing, agrees closely in substance with the two first.177

In the adventure with Melians de Lile, D. L. and 1533 again all agree against Q. in stating that he is son to the King of Denmark (W. King of Mars), thus motiving Galahad's lecture on the duties of his high station. It was certainly in Q.'s original, as he says: 'Puis ke vous estes—de si haute lignie comme de roy,' though Melians has not told him his parentage.

M., D. L., 1533, and W. are here superior to Q.

In avenging Melians on the knight who has overthrown him, M. and D. L. agree in saying that Galahad smites off the whole left arm, as against the 'poing senestre' of Q. and 1533. W. says he cuts off his nose!

In the symbolic interpretation of Melians' adventure, 1533 gives the fullest and clearest version. The right-hand road represents the Way of Our Lord, wherein His knights 'cheminent de iour et de nuyt la nuyt selon l'arme et le iour selon le corps,' 1533 (vol. iii. fo. 74), which is intelligible. Q. exactly reverses this: 'entrent de jours selon l'arme, et de nuis selon le corps.' M. gives, 'For the way on the ryƺt hand betokeneth the hyghe way of our lord Jheſu Cryſte / and the way of a true good lyver /'; W., 'On that road go the souls of the innocent,' thus evading the difficulty. D. L. is here very confused, and does not seem to have understood the passage.

In the adventure of the Castle of Maidens, M., D. L., and 1533 again agree in saying that Galahad meets seven maidens, against one in Q. M.'s '/ Soo moche peple in the stretes that he myghte not nombre them /' is evidently a rendering of 1533: 'tant de gens que il estoit impossible de les scavoir nombrer.' D. L. has exactly the same phrase, but gives 'joncfrouwen' instead of 'gens,' thus for once agreeing with Q., which gives puceles, against the other two. W. here gives 'maidens,' but in the first instance has 'a youth.'

A little later, 1533 and D. L. throw light upon an apparent contradiction between M. and Q., noted by Dr. Sommer.178 The old man of whom Galahad inquires the meaning of the adventure is, as Dr. Sommer remarks, the same who has given him the keys; but M. says he asks a 'preest.' Both 1533 and D. L. agree in saying that Galahad asks the old man who brought him the keys, when he comes to him the second time, if he be a priest, and is answered in the affirmative. Again, the three agree in giving seven years as the time the customs have been established, against the two in Q. W. here agrees in both points with 1533 and D. L.

It is plain that we must reckon this entire adventure among the agreements of M., D. L., 1533, and W., though in one particular D. L. and W. agree with Q.

In the account of the fight of Gawayne, Gareth, and Uwayne, with the seven brethren, both D. L. and 1533 give Gariët (Gaheriet) as the equivalent of Gareth.179

When Lancelot is sleeping before the Grail chapel, 1533 clearly states that the servant of the knight who has been healed takes Lancelot's sword and helmet, as well as his horse, whereas Q. only mentions the horse; but says later that Lancelot finds himself 'tot desgarnis de ses armes et de son cheval.' D. L. also only mentions the horse at the moment, but a little later on states that Lancelot is 'sonder scilt ende helm ende part,' thus practically agreeing with 1533. M. differs from both in saying that it is sword, helm, and horse of which the squire deprives him. W. here agrees with M.

M. and D. L. agree in omitting the parallel between Lancelot and the bad servant, in the Parable of the Talents, which is given by 1533 and W. But it is a noticeable feature of both D. L. and 1533 that though they give as a rule a fuller account than M., both of them shorten very considerably the improving and 'sermonising' sections which are such a feature of Q. On the other hand, both give the adventurous sections in a more accurate and detailed manner.

Perceval's interview with the recluse, in Book XIV., is clearer in D. L. than in either of the French versions, and has some special features of interest.180 Thus in Q. Perceval asks, who was the knight who overthrew him. He does not know 'ne se ch'est chil qui vint en armes vermeilles a court' (when he does not say); the recluse answers, 'Yes,' and she will tell him the 'senefianche.' In D. L. the passage runs thus: Perceval asks,

'"Oft gi wet wie die riddere esDien ic soeke berecht mi des,"Si gaf hem antwerde daer of;"Hets die gene die quam int hofIn sinxen dage, ende die danDie rode wapine hadde an.""Nu seldi mi wel berichten des,Wat betokenessen dat was?"'—ll. 3229-36.This seems to me a preferable rendering.

W. here hovers between the two versions. The aunt tells Perceval who Galahad is in answer to his question, as in D. L., but volunteers the explanation as in 1533.

Later on Perceval tells her:

'Hoe hi gevonnen hadde sijn lant,Ende sijn broder daer in es blevenMet sinen liden, mit sinen neven."Dat wet ic wel," seit si saen,"Die heilegeest deet mi verstaen,Dies ic harde blide was."'—ll. 3442-47.There is no parallel to this in the other versions, but it agrees with what we find in Morien; and I think it probable that the Dutch compiler, who seems to have been very familiar with the Perceval story, may have introduced it.181

The castle at which Perceval is to seek a kinsman is not named in D. L., but M. Goothe, W. Goth, and 1533 Got, agree against Q. there.

In Perceval's adventure with the Fiend Horse, the text of 1533 is again preferable, being clear and detailed throughout, e.g. whereas when the lady asks Perceval what he does under the tree, Q. makes him answer, 'Qu'il ne sent ni bien ne mal mais s'il eust cheval il se leva d'illuec.' 1533 gives 'qu'il ne faisoit ne bien ne mal' mais si j'avoye ung cheval ie m'en iroye d'icy.' W. here agrees with 1533.

After the fight with the dragon, M. tells us that Perceval 'caſte donne his ſheld / whiche was broken /.' Q., agreeing in the first part, omits this feature; but both D. L. and 1533 say the shield was not broken, but burnt: 'Der verbernt was wech ende wede' (3886); 'Qui estoit tout brulé' (III. fo. 83). As we have previously been told that the dragon was breathing forth flame, this is manifestly correct. W., describing the fight, says, 'his shield and breastplate were burnt all in front of him,' and that he 'threw the shield from him burning.' M., who is condensing here, omits the fiery breath, hence, I suspect, the broken instead of burnt shield.

I think we may take this again as agreement of M., D. L., W., and 1533 against Q.

The 'drois enchanteres vns multeplieres de paroles' of the French versions, with which M. closely agrees, is in D. L.:

'Hets een toverare sijt seker desDie can dinen van vele sprakenEnde van enen worde hondert maken.'—ll. 4294-6.An amplification probably due to the exigencies of rhyme;182 though as W. gives, 'He was a necromancer, who of one word would make twelve without ever saying a word of truth,' the original source may have had something similar.

M., D. L., and W. again agree against Q. and 1533 in giving a shorter version of Perceval's prayer, and omitting all New Testament references.

The adventure of the dead hermit, in Book XV., is, again, better told in D. L. and 1533 than in M. or Q. Thus Q. omits to state the nature of the supposed transgression, which is clearly set forth in the other three:

'Maer hine es niet, donket mi,Na sire ordinen gebode,Noch na onsen herre Gode;Want hi niet heden den dachIn sulken abite sterven ne mach,Hine hebbe bi enegen onmatenSine ordine nu gelaten.'—ll. 4780-87.This is evidently the source of M.'s 'this man that is dede oughte not to be in suche clothynge as ye see hym in / for in that he brake the othe of his ordre /.' W. gives the same reason at greater length.

Later on M. seems to have had before him a reading nearer to Q.: in the morning, 'il trouuerent sans faille le preudhomme de vie,' which M. understood as alive, since he says, 'he laye all that nygt tyl hit was daye in that fyre and was not dede /,' though immediately afterwards he says that the Hermit came and found him dead. D. L. and 1533 say, 'Ende alse dat vier utginc si vonden Den goeden man doet tien stonden,' ll. 4915-16; 'ilz trouverent sans nulle faulte le preudhomme mort.' The miracle consisting in the fact that his garments (e.g. the linen shirt) were untouched by fire, so that he evidently had died from the previous ill-usage, not from the burning—a result which he had predicted. W., on the contrary, says that 'when the fire was extinguished the man was as lively as he was before. And then he prayed Jesus Christ to take his soul to Him, and He received him, without injury to the shirt or himself.' The whole adventure should be carefully compared, and the superiority of these three versions will be clearly seen. The two first are, I think, the correct version of the incident, but W., though rendering freely, gives a fuller account than is often the case.

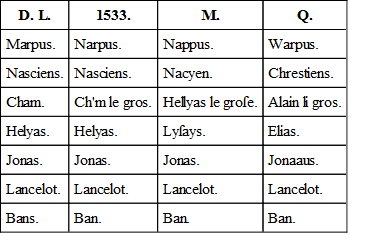

The list of Celidoine's descendants agrees in D. L. and 1533, while M., though varying from the other three, leans rather to these two than to Q.:

I think here the second name is certainly Nasciens, and that the mysterious Cham of D. L. and 1533 (a personage whom we do not know) ought probably to be Alain. Such a mistake might easily be made by a copyist, if the MS. before him were not clear and he was unfamiliar with Grail traditions. I think it very likely that M.'s source was much the same as that of D. L. and 1533, and that he dropped out Cham, but the comparison of the four versions is interesting. The list is omitted in W.