полная версия

полная версияTravels on the Amazon

Each family has a separate house, which is small, of a square shape, and possesses both a door and windows; and the houses are collected together in little scattered villages. The Isánna Indians make small flat baskets like those of the Uaupés, but not the stools, nor the aturás, neither have they the white cylindrical stone which the others so much esteem. They marry one, two, or three wives, and prefer relations, marrying with cousins, uncles with nieces, and nephews with aunts, so that in a village all are connected. The men are more warlike and morose in their disposition than the Uaupés, by whom they are much feared. They bury their dead in their houses, and mourn for them a long time, but make no feast on the occasion. The Isánna Indians are said not to be nearly so numerous, nor to increase so rapidly, as the Uaupés; which may perhaps be owing to their marrying with relations, while the former prefer strangers.

The Arekaínas make war against other tribes, to obtain prisoners for food, like the Cobeus. In their superstitions and religious ideas they much resemble the Uaupés.

The Macás are one of the lowest and most uncivilised tribes of Indians in the Amazon district. They inhabit the forests and serras about the rivers Marié, Curicuriarí, and Urubaxí, and live a wandering life, having no houses and no fixed place of abode, and of course no clothing; they have little or no iron, and use the tusks of the wild pig to scrape and form their bows and arrows, and they make a most deadly kind of poison to anoint them. At night they sleep on a bundle of palm-leaves, or stick up a few leaves to make a shed if it rains, or sometimes, with "sipós," construct a rude hammock, which, however, serves only once. They eat all kinds of birds and fish, roasted or boiled in palm-spathes; and all sorts of wild fruits.

The Macás often attack the houses of other Indians situated in solitary places, and murder all the inhabitants; and they have even depopulated and caused the removal of several villages. All the other tribes of Indians catch them and keep them as slaves, and in most villages you will see some of them. They are distinguishable at once from the surrounding tribes by a wavy and almost curly hair, and by being rather lanky and ill-formed in their limbs: I am inclined, however, to think that this latter is partly owing to their mode of life, and the hardships and exposure they have to undergo; and some that I have seen in the houses of traders have been as well-formed and handsome as any of the other Indian tribes.

The Curetús are a nation inhabiting the country about the river Apaporís, between the Japurá and Uaupés. I met with some Indians of this tribe on the Rio Negro, and the only peculiarity I observed in them was, that their cheek-bones were rather more prominent than usual. From them, and from an Isánna Indian who had visited them, I obtained some information about their customs.

They wear their hair long like the Uaupés, and, like them, the women go entirely naked; and they paint their bodies, but do not tattoo. Their houses are large and circular, with walls of thatch, and a high conical capped roof, made like some chimney-pots, with the upper part overlapping, so as to let the smoke escape without allowing the rain to enter. They do not wander about, but reside in small permanent villages, governed by a chief, and are said to be long-lived and very peaceable, never quarrelling or making war with other nations. The men have but one wife. There are no pagés, or priests, among them, and they have no ideas of a superior Being. They cultivate mandiocca, maize, and other fruits, and use game more than fish for food. No civilised man has ever been among them, so they have no salt, and a very scanty supply of iron, and obtain fire by friction. It is said also that they differ from most other tribes in making no intoxicating drinks. Their language is full of harsh and aspirated sounds, and is somewhat allied to those of the Tucanos and Cobeus among the Uaupés.

In the lower part of the Japurá reside the "Uaenambeus," or Humming-bird Indians. I met with some of them in the Rio Negro, and obtained some information as to their customs and language. In most particulars they much resemble the last-mentioned tribe, particularly in their circular houses, their food, and mode of life. Like them they weave the fibres of the Tucúm palm-leaf (Astrocaryum vulgare) to make their hammocks, whereas the Uaupés and Isánna Indians always use the leaf of the Mirití (Mauritia flexuosa). They are distinguished from other tribes by a small blue mark on the upper lip. They have from one to four wives, and the women always wear a small apron of bark.

Closely allied to these are the Jurís of the Solimões, between the Iça and Japurá. A number of them have migrated to the Rio Negro, and become settled and partly civilised there. They are remarkable for a custom of tattooing in a circle (not in a square, as in a plate in Dr. Prichard's work) round the mouth, so as exactly to resemble the little black-mouthed squirrel-monkeys (Callithrix sciureus); from this cause they are often called the Juripixúnas (Black Juris), or by the Brazilians "Bocapreitos" (Black-mouths). From this strange errors have arisen: we find in some maps the note "Juries, curly-haired Negroes," whereas they are pure straight-haired Indians. They are good servants for canoe and agricultural work, and are the most skilful of all in the use of the gravatána, or blow-pipe.

In the same neighbourhood are Miránhas, who are cannibals; and the Ximánas and Cauxánas, who kill all their first-born children: in fact, between the Upper Amazon, the Guaviare, and the Andes, there is a region as large as England, whose inhabitants are entirely uncivilised and unknown.

On the south side of the Amazon also, between the Madeira and the Uaycáli, and extending to the Andes of Peru and Bolivia, is a still larger tract of unknown virgin forest, uninhabited by a single civilised man: here reside numerous nations of the native American race, known only by the reports of the border tribes, who form the communication between them and the traders of the great rivers.

One of the best-known and most regularly visited rivers of this great tract is the Purús, whose mouth is a short distance above the Rio Negro, but whose sources a three months' voyage does not reach. Of the Indians found on the banks of this river I have been able to get some information.

Five tribes are met with by the traders:—

1. Múras, from the mouth to sixteen days' voyage up.

2. Purupurús, from thence to about thirty days' voyage up.

3. Catauxís, in the district of the Purupurús, but in the igaripés and lakes inland.

4. Jamamarís, inland on the west bank.

5. Jubirís, on the river-banks above the Purupurús.

The Múras are rather a tall race, have a good deal of beard for Indians, and the hair of the head is slightly crisp and wavy. They used formerly to go naked, but now the men all wear trousers and shirts, and the women petticoats. Their houses are grouped together in small villages, and are scarcely ever more than a roof supported on posts; very rarely do they take the trouble to build any walls. They make no hammocks, but hang up three bands of a bark called "invíra," on which they sleep; but the more civilised now purchase of the traders hammocks made by other Indians. They practise scarcely any cultivation, except sometimes a little mandiocca, but generally live on wild fruits, and abundance of fish and game: their food is entirely produced by the river, consisting of the Manatus, or cow-fish, which is as good as beef, turtles, and various kinds of fish, all of which are in great abundance, so that the traders say there are no people who live so well as the Múras; they have therefore no occasion for gravatánas, which they do not make, but have a great variety of bows and arrows and harpoons, and construct very good canoes. They now all cut their hair; the old men have a large hole in their lower lip filled up with a piece of wood, but this custom is now disused. Each man has two or three wives, but there is no ceremony of marriage; and they bury their dead sometimes in the house, but more commonly outside, and putting the goods of the deceased upon his grave. The women use necklaces and bracelets of beads, and the men tie the seeds of the india-rubber tree to their legs when they dance. Each village has a Tushaúa: the succession is hereditary, but the chief has very little power. They have pagés, whom they believe to have much skill, and are afraid of, and pay well. They were formerly very warlike, and made many attacks upon the Europeans, but are now much more peaceful; and are the most skilful of all Indians in shooting turtles and fish, and in catching the cow-fish. They still use their own language among themselves, though they also understand the Lingoa Geral. The white traders obtain from them salsaparilha, oil from turtles' eggs and the cow-fish, Brazil-nuts, and estopa, which is the bark of the young Brazil-nut tree (Bertholletia excelsa), used extensively for caulking canoes; and pay them in cotton goods, harpoon and arrow-heads, hooks, beads, knives, cutlasses, etc.

The next tribes, the Purupurús, are in many respects very peculiar, and differ remarkably in their habits from any other nation we have yet described. They call themselves Pamouirís, but are always called by the Brazilians Purupurús, a name also applied to a peculiar disease, with which they are almost all afflicted: this consists in the body being spotted and blotched with white, brown, or nearly black patches, of irregular size and shape, and having a very disagreeable appearance: when young, their skins are clear, but as they grow up, they invariably become more or less spotted. Other Indians are sometimes seen afflicted in this manner, and they are then said to have the Purupurú; though it does not appear whether the disease is called after the tribe of Indians who are most subject to it, or the Indians after the disease. Some say that the word is Portuguese, but this seems to be a mistake.

The Purupurús, men and women, go perfectly naked; and their houses are of the rudest construction, being semi-cylindrical, like those of our gipsies, and so small, as to be set up on the sandy beaches and carried away in their canoes whenever they wish to move. These canoes are of the rudest construction, having a flat bottom and upright sides,—a mere square box, and quite unlike those of all other Indians. But what distinguishes them yet more from their neighbours is, that they use neither the gravatána, nor bow and arrows, but have an instrument called a "palheta," which is a piece of wood with a projection at the end, to secure the base of the arrow, the middle of which is held with the handle of the palheta in the hand, and thus thrown as from a sling: they have a surprising dexterity in the use of this weapon, and with it readily kill game, birds, and fish.

They grow a few fruits, such as yams and plantains, but seldom have any mandiocca, and they construct earthen pans to cook in. They sleep in their houses on the sand of the prayas, making no hammocks or clothing of any kind; they make no fires in their houses, which are too small, but are kept warm at night by the number of persons in them. They bore large holes in the upper and lower lip, in the septum of the nose, and in the ears; at their festivals they insert in these holes sticks, six or eight inches long; at other times they have only a short piece in, to keep them open. In the wet season, when the prayas and banks of the river are all flooded, they construct rafts of trunks of trees bound together with creepers, and on them erect their huts, and live there till the waters fall again, when they guide their raft to the first sandy beach that appears.

Little is known of their domestic customs and superstitions. The men have each but one wife; the dead are buried in the sandy beaches; and they are not known to have any pagés. A few families only live together, in little movable villages, to each of which there is a Tushaúa. They have, at times, dances and festivals, when they make intoxicating drinks from wild fruits, and amuse themselves with rude musical instruments, formed of reeds and bones. They do not use salt, but prefer payment in fish-hooks, knives, beads, and farinha, for the salsaparilha and turtle-oil which they sell to the traders.

May not the curious disease, to which they are so subject, be produced by their habit of constantly sleeping naked on the sand, instead of in the comfortable, airy, and cleanly hammock, so universally used by almost every other tribe of Indians in this part of South America?

The Catauixis, though in the immediate neighbourhood of the last, are very different. They have permanent houses, cultivate mandiocca, sleep in hammocks, and are clean-skinned. They go naked like the last, but do not bore holes in their nose and lips; they wear a ring of twisted hair on their arms and legs. They use bows, arrows, and gravatánas, and make the ervadúra, or ururí poison. Their canoes are made of the bark of a tree, taken off entire. They eat principally forest game, tapirs, monkeys, and large birds; they are, however, cannibals, killing and eating any Indians of other tribes they can procure, and they preserve the meat, smoked and dried. Senhor Domingos, a Portuguese trader up the river Purús, informed me that he once met a party of them, who felt his belly and ribs, as a butcher would handle a sheep, and talked much to each other, apparently intimating that he was fat, and would be excellent eating.

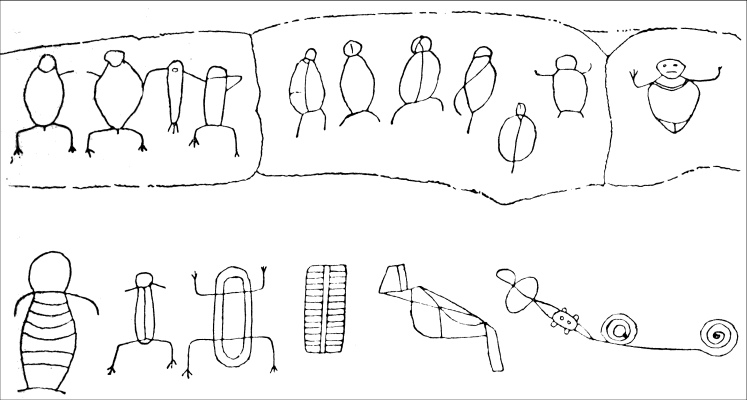

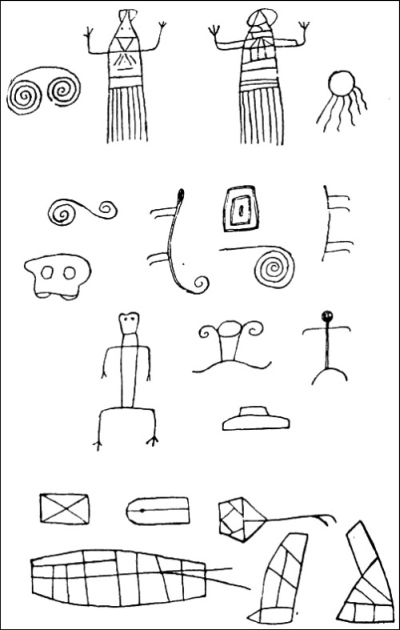

PLATE VIII.

FIGURES ON THE GRANITE ROCKS OF THE RIVER UAUPÉS.

PLATE IX.

FIGURES ON THE GRANITE ROCKS OF THE RIVER UAUPÉS.

Of the Jamamarís we have no authentic information, but that they much resemble the last in their manners and customs, and in their appearance.

The Jubirís are equally unknown; they, however, most resemble the Purupurús in their habits and mode of life, and, like them, have their bodies spotted and mottled, though not to such a great extent.

In the country between the Tapajóz and the Madeira, among the labyrinth of lakes and channels of the great island of the Tupinambarános, reside the Mundrucús, the most warlike Indians of the Amazons. These are, I believe, the only perfectly tattooed nation in South America: the markings are extended all over the body; they are produced by pricking with the spines of the pupunha palm, and rubbing in the soot from burning pitch to produce the indelible bluish tinge.

They make their houses with mud walls, in regular villages. In each village they have a large building which serves as a kind of barrack, or fortress, where all the men sleep at night, armed with their bows and arrows, ready in case of alarm: this house is surrounded within with dried heads of their enemies: these heads they smoke and dry, so as to preserve all the features and the hair most perfectly. They make war every year with an adjoining tribe, the Parentintins, taking the women and children for slaves, and preserving the heads of the men. They make good canoes and hammocks. They live principally on forest-game, and are very agricultural, making quantities of farinha and growing many fruits. The men have each one wife, and each village its chief. Cravo or wild nutmegs, and farinha, are the principal articles of their trade; and they receive in exchange cotton cloth, iron goods, salt, beads, etc.

In the Rio Branco are numerous tribes, and some of them are said to practise circumcision.

Others, near the sources of the Tapajóz, make the girls undergo the same cruel initiation as has been already described as common among the Uaupés and Isánna Indians.

On the north banks of the Rio Negro are many uncivilised tribes, very little known.

On the south banks, the Manaós were formerly a very numerous nation. It appears to have been from these tribes that the various accounts of imaginary wealth prevalent soon after the discovery of America were derived; the whole of them are now civilised, and their blood mingles with that of some of the best families in the Province of Pará; their language is said still to exist, and to be spoken by many old persons, but I was never fortunate enough to meet with any one understanding it.

One of the singular facts connected with these Indians of the Amazon valley, is the resemblance which exists between some of their customs, and those of nations most remote from them. The gravatána, or blow-pipe, reappears in the sumpitan of Borneo; the great houses of the Uaupés closely resemble those of the Dyaks of the same country; while many small baskets and bamboo-boxes, from Borneo and New Guinea, are so similar in their form and construction to those of the Amazon, that they would be supposed to belong to adjoining tribes. Then again the Mundrucús, like the Dyaks, take the heads of their enemies, smoke-dry them with equal care, preserving the skin and hair entire, and hang them up around their houses. In Australia the throwing-stick is used; and, on a remote branch of the Amazon, we see a tribe of Indians differing from all around them, in substituting for the bow a weapon only found in such a remote portion of the earth, among a people differing from them in almost every physical character.

It will be necessary to obtain much more information on this subject, before we can venture to decide whether such similarities show any remote connection between these nations, or are mere accidental coincidences, produced by the same wants, acting upon people subject to the same conditions of climate and in an equally low state of civilisation; and it offers additional matter for the wide-spreading speculations of the ethnographer.

The main feature in the personal character of the Indians of this part of South America, is a degree of diffidence, bashfulness, or coldness, which affects all their actions. It is this that produces their quiet deliberation, their circuitous way of introducing a subject they have come to speak about, talking half an hour on different topics before mentioning it: owing to this feeling, they will run away if displeased rather than complain, and will never refuse to undertake what is asked them, even when they are unable or do not intend to perform it.

It is the same peculiarity which causes the men never to exhibit any feeling on meeting after a separation; though they have, and show, a great affection for their children, whom they never part with; nor can they be induced to do so, even for a short time. They scarcely ever quarrel among themselves, work hard, and submit willingly to authority. They are ingenious and skilful workmen, and readily adopt any customs of civilised life that may be introduced among them; and they seem capable of being formed, by education and good government, into a peaceable and civilised community.

This change, however, will, perhaps, never take place: they are exposed to the influence of the refuse of Brazilian society, and will probably, before many years, be reduced to the condition of the other half-civilised Indians of the country, who seem to have lost the good qualities of savage life, and gained only the vices of civilisation.

APPENDIX

ON AMAZONIAN PICTURE-WRITINGSAs connected with the languages of these people, we may mention the curious figures on the rocks commonly known as picture-writings, which are found all over the Amazon district.

The first I saw was on the serras of Montealegre, as described in my Journal (p. 104). These differed from all I have since seen, in being painted or rubbed in with a red colour, and not cut or scratched as in most of the others I met with. They were high up on the mountain, at a considerable distance from any river.

The next I fell in with were on the banks of the Amazon, on rocks covered at high water just below the little village of Serpa. These figures are principally of the human face, and are roughly cut into the hard rock, blackened by the deposit which takes place in the waters of the Amazon, as in those of the Orinooko.

Again, at the mouth of the Rio Branco, on a little rocky island in the river, are numerous figures of men and animals of a large size scraped into the hard granitic rock. Near St. Isabel, S. Jozé, and Castanheiro, there are more of these figures, and I found others on the Upper Rio Negro in Venezuela. I took careful drawings of all of them,—which are unfortunately lost.

In the river Uaupés also these figures are very numerous, and of these I preserved my sketches. They contain rude representations of domestic utensils, canoes, animals, and human figures, as well as circles, squares, and other regular forms. They are all scraped on the excessively hard granitic rock. Some are entirely above and others below high-water mark, and many are quite covered with a growth of lichens, through which, however, they are still plainly visible. (Plates VIII. and IX.) Whether they had any signification to those who executed them, or were merely the first attempts of a rude art guided only by fancy, it is impossible now to say. It is, however, beyond a doubt that they are of some antiquity, and are never executed by the present race of Indians. Even among the most uncivilised tribes, where these figures are found, they have no idea whatever of their origin; and if asked, will say they do not know, or that they suppose the spirits did them. Many of the Portuguese and Brazilian traders will insist upon it that they are natural productions, or, to use their own expression, that "God made them;" and on any objection being made they triumphantly ask, "And could not God make them?" which of course settles the point. Most of them in fact are quite unable to see any difference between these figures and the natural marks and veins that frequently occur in the rocks.

1

"Bemteví" (I saw you well); the bird's note resembles this word.

2

This is a blood-sucking bat (Phyllostoma sp.), misnamed "vampyre," while the bats of the genus Vampyrus are fruit-eaters.

3

Mingau is a kind of porridge made either of farinha or of the large plantain called pacova.

4

The sandstone rocks of Montealegre have since been ascertained to be of cretaceous age.

5

The isolated granite domes and pillars show that the whole area has been formerly covered with thick sedimentary rocks, which have been removed by denudation.

6

As so few Europeans have seen these large serpents, and the very existence of any large enough to swallow a horse or ox is hardly credited, I append the following account by a competent scientific observer, the well-known botanical traveller Dr. Gardner. In his "Travels in Brazil," p. 356, he says:—

"In the marshes of this valley in the province of Goyaz, near Arrayas, the Boa Constrictor is often met with of considerable size; it is not uncommon throughout the whole province, particularly by the wooded margins of lakes, marshes, and streams. Sometimes they attain the enormous length of forty feet: the largest I ever saw was at this place, but it was not alive. Some weeks before our arrival at Safê, the favourite riding horse of Senhor Lagoriva, which had been put out to pasture not far from the house, could not be found, although strict search was made for it all over the Fazenda. Shortly after this, one of his vaqueiros, in going through a wood by the side of a small river, saw an enormous Boa suspended in the fork of a tree which hung over the water; it was dead, but had evidently been floated down alive by a recent flood, and being in an inert state it had not been able to extricate itself from the fork before the waters fell. It was dragged out to the open country by two horses, and was found to measure thirty-seven feet in length; on opening it the bones of a horse in a somewhat broken condition, and the flesh in a half-digested state, were found within it, the bones of the head being uninjured; from these circumstances we concluded that the Boa had devoured the horse entire."

7

Specimens of Nos. 1, 2, 3, 9, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 21, 34, 36, 41, 47, 49, and 63, of this list, have been sent home by my friend R. Spruce, Esq., and may be seen in the very interesting Museum at the Royal Botanical Gardens, at Kew.