полная версия

полная версияTravels on the Amazon

They have always in their houses a large supply of earthen pots, pans, pitchers, and cooking utensils, of various sizes, which they make of clay from the river and brooks, mixed with the ashes of the caripé bark, and baked in a temporary furnace. They have also great quantities of small saucer-shaped baskets, called "Balaios," which are much esteemed down the river, and are the subject of a considerable trade.

Two tribes in the lower part of the river, the Tariános and Tucános, make a curious little stool, cut from a solid block of wood, and neatly painted and varnished; these, which take many days to finish, are sold for about a pennyworth of fish-hooks.

Their canoes are all made out of a single tree, hollowed and forced open by the cross-benches; they are very thick in the middle, to resist the wear and tear they are exposed to among the rocks and rapids; they are often forty feet long, but smaller ones are generally preferred. The paddles are about three feet long, with an oval blade, and are each cut out of one piece of wood.

These people are as free from the encumbrances of dress as it is possible to conceive. The men wear only a small piece of tururí passed between the legs, and twisted on to a string round the loins. Even such a costume as this is dispensed with by the women: they have no dress or covering whatever, but are entirely naked. This is the universal custom among the Uaupés Indians, from which, in a state of nature, they never depart. Paint, with these people, seems to be looked upon as a sufficient clothing; they are never without it on some part of their bodies, but it is at their festivals that they exhibit all their art in thus decorating their persons: the colours they use are red, yellow, and black, and they dispose them generally in regular patterns, similar to those with which they ornament their stools, their canoes, and other articles of furniture.

They pour the juice of a tree, which stains a deep blue-black, on their heads, and let it run in streams all down their backs; and the red and yellow are often disposed in large round spots upon the cheeks and forehead.

The use of ornaments and trinkets of various kinds is almost confined to the men. The women wear a bracelet on the wrists, but none on the neck, and no comb in the hair; they have a garter below the knee, worn tight from infancy, for the purpose of swelling out the calf, which they consider a great beauty. While dancing in their festivals, the women wear a small tanga, or apron, made of beads, prettily arranged; it is only about six inches square, but is never worn at any other time, and immediately the dance is over, it is taken off.

The men, on the other hand, have the hair carefully parted and combed on each side, and tied in a queue behind. In the young men, it hangs in long locks down their necks, and, with the comb, which is invariably carried stuck in the top of the head, gives to them a most feminine appearance: this is increased by the large necklaces and bracelets of beads, and the careful extirpation of every symptom of beard. Taking these circumstances into consideration, I am strongly of opinion that the story of the Amazons has arisen from these feminine-looking warriors encountered by the early voyager. I am inclined to this opinion, from the effect they first produced on myself, when it was only by close examination I saw that they were men; and, were the front parts of their bodies and their breasts covered with shields, such as they always use, I am convinced any person seeing them for the first time would conclude they were women. We have only therefore to suppose that tribes having similar customs to those now living on the river Uaupés, inhabited the regions where the Amazons were reported to have been seen, and we have a rational explanation of what has so much puzzled all geographers. The only objection to this explanation is, that traditions are said to exist among the natives, of a nation of "women without husbands." Of this tradition, however, I was myself unable to obtain any trace, and I can easily imagine it entirely to have arisen from the suggestions and inquiries of Europeans themselves. When the story of the Amazons was first made known, it became of course a point with all future travellers to verify it, or if possible get a glimpse of these warlike ladies. The Indians must no doubt have been overwhelmed with questions and suggestions about them, and they, thinking that the white men must know best, would transmit to their descendants and families the idea that such a nation did exist in some distant part of the country. Succeeding travellers, finding traces of this idea among the Indians, would take it as a proof of the existence of the Amazons; instead of being merely the effect of a mistake at the first, which had been unknowingly spread among them by preceding travellers, seeking to obtain some evidence on the subject.

In my communications and inquiries among the Indians on various matters, I have always found the greatest caution necessary, to prevent one's arriving at wrong conclusions. They are always apt to affirm that which they see you wish to believe, and, when they do not at all comprehend your question, will unhesitatingly answer, "Yes." I have often in this manner obtained, as I thought, information, which persons better acquainted with the facts have assured me was quite erroneous. These observations, however, must only be taken to apply to those almost uncivilised nations who do not understand, at all clearly, any language in which you can communicate with them. I have always been able to rely on what is obtained from Indians speaking Portuguese readily, and I believe that much trustworthy information can be obtained from them. Such, however, is not the case with the wild tribes, who are totally incapable of understanding any connected sentence of the language in which they are addressed; and I fear the story of the Amazons must be placed with those of the wild man-monkeys, which Humboldt mentions and which tradition I also met with, and of the "curupíra," or demon of the woods, and "carbunculo," of the Upper Amazon and Peru; but of which superstitions we have no such satisfactory elucidation as I think has been now given of the warlike Amazons.

To return to our Uaupés Indians and their toilet. We find their daily costume enlivened with a few other ornaments; a circlet of parrots' tail-feathers is generally worn round the head, and the cylindrical white quartz-stone, already described in my Narrative (p. 191), is invariably carried on the breast, suspended from a necklace of black seeds.

At festivals and dances they decorate themselves with a complicated costume of feather head-dresses, cinctures, armlets, and leg ornaments, which I have sufficiently described in the account of their dances (p. 202).

We will now describe some peculiarities connected with their births, marriages, and deaths.

The women are generally delivered in the house, though sometimes in the forest. When a birth takes place in the house, everything is taken out of it, even the pans and pots, and bows and arrows, till the next day; the mother takes the child to the river and washes herself and it, and she generally remains in the house, not doing any work, for four or five days.

The children, more particularly the females, are restricted to a particular food: they are not allowed to eat the meat of any kind of game, nor of fish, except the very small bony kinds; their food principally consisting of mandiocca-cake and fruits.

On the first signs of puberty in the girls, they have to undergo an ordeal. For a month previously, they are kept secluded in the house, and allowed only a small quantity of bread and water. All relatives and friends of the parents are then assembled, bringing, each of them, pieces of "sipó" (an elastic climber); the girl is then brought out, perfectly naked, into the midst of them, when each person present gives her five or six severe blows with the sipó across the back and breast, till she falls senseless, and it sometimes happens, dead. If she recovers, it is repeated four times, at intervals of six hours, and it is considered an offence to the parents not to strike hard. During this time numerous pots of all kinds of meat and fish have been prepared, when the sipós are dipped in them and given to her to lick, and she is then considered a woman, and allowed to eat anything, and is marriageable.

The boys undergo a somewhat similar ordeal, but not so severe; which initiates them into manhood, and allows them to see the Juruparí music, which will be presently described.

Tattooing is very little practised by these Indians; they all, however, have a row of circular punctures along the arm, and one tribe, the Tucános, are distinguished from the rest by three vertical blue lines on the chin; and they also pierce the lower lip, through which they hang three little threads of white beads. All the tribes bore their ears, and wear in them little pieces of grass, ornamented with feathers. The Cobeus alone expand the hole to so large a size, that a bottle-cork could be inserted: they ordinarily wear a plug of wood in it, but, on festas, insert a little bunch of arrows.

The men generally have but one wife, but there is no special limit, and many have two or three, and some of the chiefs more; the elder one is never turned away, but remains the mistress of the house. They have no particular ceremony at their marriages, except that of always carrying away the girl by force, or making a show of doing so, even when she and her parents are quite willing. They do not often marry with relations, or even neighbours,—preferring those from a distance, or even from other tribes. When a young man wishes to have the daughter of another Indian, his father sends a message to say he will come with his son and relations to visit him. The girl's father guesses what it is for, and, if he is agreeable, makes preparations for a grand festival: it lasts, perhaps, two or three days, when the bridegroom's party suddenly seize the bride, and hurry her off to their canoes; no attempt is made to prevent them, and she is then considered as married.

Some tribes, as the Uacarrás, have a trial of skill at shooting with the bow and arrow, and if the young man does not show himself a good marksman, the girl refuses him, on the ground that he will not be able to shoot fish and game enough for the family.

The dead are almost always buried in the houses, with their bracelets, tobacco-bag, and other trinkets upon them: they are buried the same day they die, the parents and relations keeping up a continual mourning and lamentation over the body, from the death to the time of interment; a few days afterwards, a great quantity of caxirí is made, and all friends and relations invited to attend, to mourn for the dead, and to dance, sing, and cry to his memory. Some of the large houses have more than a hundred graves in them, but when the houses are small, and very full, the graves are made outside.

The Tariánas and Tucános, and some other tribes, about a month after the funeral, disinter the corpse, which is then much decomposed, and put it in a great pan, or oven, over the fire, till all the volatile parts are driven off with a most horrible odour, leaving only a black carbonaceous mass, which is pounded into a fine powder, and mixed in several large couchés (vats made of hollowed trees) of caxirí: this is drunk by the assembled company till all is finished; they believe that thus the virtues of the deceased will be transmitted to the drinkers.

The Cobeus alone, in the Uaupés, are real cannibals: they eat those of other tribes whom they kill in battle, and even make war for the express purpose of procuring human flesh for food. When they have more than they can consume at once, they smoke-dry the flesh over the fire, and preserve it for food a long time. They burn their dead, and drink the ashes in caxirí, in the same manner as described above.

Every tribe and every "malocca" (as their houses are called) has its chief, or "Tushaúa," who has only a limited authority, principally in war, in making festivals, and in repairing the malocca and keeping the village clean, and in planting the mandiocca-fields; he also treats with the traders, and supplies them with men to pursue their journeys. The succession of these chiefs is strictly hereditary in the male line, or through the female to her husband, who may be a stranger: their regular hereditary chief is never superseded, however stupid, dull, or cowardly he may be. They have very little law of any kind; but what they have is of strict retaliation,—an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth; and a murder is punished or revenged in the same manner and by the same weapon with which it was committed.

They have numerous "Pagés," a kind of priests, answering to the "medicine-men" of the North American Indians. These are believed to have great power: they cure all diseases by charms, applied by strong blowing and breathing upon the party to be cured, and by the singing of certain songs and incantations. They are also believed to have power to kill enemies, to bring or send away rain, to destroy dogs or game, to make the fish leave a river, and to afflict with various diseases. They are much consulted and believed in, and are well paid for their services. An Indian will give almost all his wealth to a pagé, when he is threatened with any real or imaginary danger.

They scarcely seem to think that death can occur naturally, always imputing it either to direct poisoning or the charms of some enemy, and, on this supposition, will proceed to revenge it. This they generally do by poisons, of which they have many which are most deadly in their effects: they are given at some festival in a bowl of caxirí, which it is good manners always to empty, so that the whole dose is sure to be taken. One of the poisons often used is most terrible in its effects, causing the tongue and throat, as well as the intestines, to putrefy and rot away, so that the sufferer lingers some days in the greatest agony: this is of course again retaliated, on perhaps the wrong party, and thus a long succession of murders may result from a mere groundless suspicion in the first instance.

I cannot make out that they have any belief that can be called a religion. They appear to have no definite idea of a God; if asked who they think made the rivers, and the forests, and the sky, they will reply that they do not know, or sometimes that they suppose it was "Tupánau," a word that appears to answer to God, but of which they understand nothing. They have much more definite ideas of a bad spirit, "Juruparí," or Devil, whom they fear, and endeavour through their pagés to propitiate. When it thunders, they say the "Juruparí" is angry, and their idea of natural death is that the "Juruparí" kills them. At an eclipse they believe that this bad spirit is killing the moon, and they make all the noise they can to frighten him away.

One of their most singular superstitions is about the musical instruments they use at their festivals, which they call the Juruparí music. These consist of eight or sometimes twelve pipes, or trumpets, made of bamboos or palm-stems hollowed out, some with trumpet-shaped mouths of bark and with mouth-holes of clay and leaf. Each pair of instruments gives a distinct note, and they produce a rather agreeable concert, something resembling clarionets and bassoons. These instruments, however, are with them such a mystery that no woman must ever see them, on pain of death. They are always kept in sone igaripé, at a distance from the malocca, whence they are brought on particular occasions: when the sound of them is heard approaching, every woman retires into the woods, or into some adjoining shed, which they generally have near, and remains invisible till after the ceremony is over, when the instruments are taken away to their hiding-place, and the women come out of their concealment. Should any female be supposed to have seen them, either by accident or design, she is invariably executed, generally by poison, and a father will not hesitate to sacrifice his daughter, or a husband his wife, on such an occasion.

They have many other prejudices with regard to women. They believe that if a woman, during her pregnancy, eats of any meat, any other animal partaking of it will suffer: if a domestic animal or tame bird, it will die; if a dog, it will be for the future incapable of hunting; and even a man will ever after be unable to shoot that particular kind of game. An Indian, who was one of my hunters, caught a fine cock of the rock, and gave it to his wife to feed, but the poor woman was obliged to live herself on cassava-bread and fruits, and abstain entirely from all animal food, peppers, and salt, which it was believed would cause the bird to die; notwithstanding all precautions, however, the bird did die, and the woman got a beating from her husband, because he thought she had not been sufficiently rigid in her abstinence from the prohibited articles.

Most of these peculiar practices and superstitions are retained with much tenacity, even by those Indians who are nominally civilised and Christian, and many of them have been even adopted by the Europeans resident in the country: there are actually Portuguese in the Rio Negro who fear the power of the Indian pagés, and who fully believe and act on all the Indian superstitions respecting women.

The river Uaupés is the channel by which European manufactures find their way into the extensive and unknown regions between the Rio Guaviare on the one side, and the Japurá on the other. About a thousand pounds worth of goods enter the Uaupés yearly, mostly in axes, cutlasses, knives, fish-hooks, arrow-heads, salt, mirrors, beads, and a few cottons.

The articles given in exchange are salsaparilha, pitch, farinha, string, hammocks, and Indian stools, baskets, feather ornaments, and curiosities. The salsaparilha is by far the most valuable product, and is the only one exported. Great quantities of articles of European manufacture are exchanged by the Indians with those of remote districts, for the salsa which they give to the traders; and thus numerous tribes, among whom no civilised man has ever yet penetrated, are well supplied with iron goods, and send the product of their labour to European markets.

In order to give some idea of the state of industry and the arts among these people, I subjoin a list of articles which I collected when among them, to illustrate their manners, customs, and state of civilisation, but which were unfortunately all lost on my passage home.

LIST OF ARTICLES MANUFACTURED BY THE INDIANS OF THE RIO DOS UAUPÉSHousehold Furniture and Utensils1. Hammocks, or maqueiras, of palm-fibre, of various materials, colours, and texture.

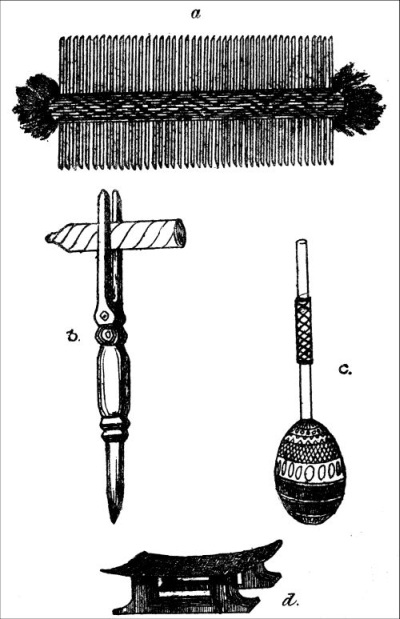

2. Small wooden stools, of various sizes, painted and varnished. (Plate VII. d.)

3. Flat baskets of plaited bark, in regular patterns and of various colours.

4. Deeper baskets, called "Aturás." (Plate VI. d.)

5. Calabashes and gourds, of various shapes and sizes.

6. Water-pitchers of earthenware.

7. Pans of earthenware for cooking.

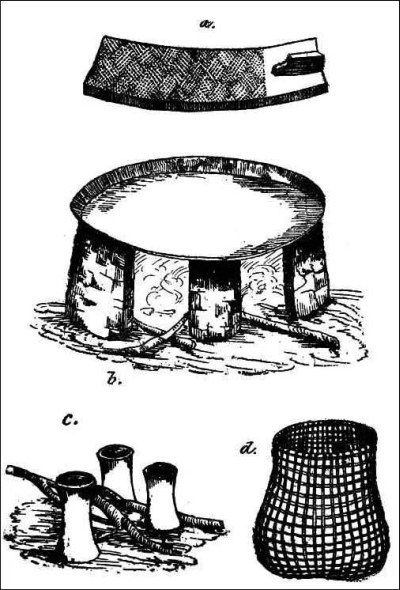

Articles used in the Manufacture of Mandiocca Bread8. Mandiocca graters, of quartz fragments set in wood. (Plate VI. a.)

9. Tipitis, or wicker elastic pressure cylinders.

10. Wicker sieves for straining the pulp.

11. Ovens for roasting cassava-bread and farinha. (Plate VI. b.)

12. Plaited fans for blowing the fire and turning the cakes.

Weapons used in War, Hunting, and Fishing13. Bows of various woods and different sizes.

14. Quivers of curabís, or poisoned war-arrows.

15. Arrows with heads of monkey-bones.

16. Arrows, with iron heads, for shooting fish.

17. Gravatánas, or blow-tubes, from eight to fourteen feet long.

18. Wicker and wooden quivers, with poisoned arrows for them.

19. Small pots and calabashes, with the curarí or ururí poison.

20. Large carved clubs of hard wood.

21. Carved and feather ornamented lances.

22. Large circular shields of wicker-work.

23. Ditto, covered with tapir's skin.

24. Nets for fishing (Pisás).

25. Rod and line for fishing.

26. Palm-spine fish-hooks.

27. Small wicker traps for catching fish (Matapís).

PLATE VI.

a. Mandioca grater. b. Oven. c. Fire place d. Basket.

INDIAN IMPLEMENTS AND DOMESTIC ARTICLES.

PLATE VII.

a. Comb b. Cigar holder c. Rattle d. Stool

INDIAN IMPLEMENTS AND DOMESTIC ARTICLES.

Musical Instruments

28. A small drum.

29. Eight large trumpets, the Juruparí music.

30. Numerous fifes and flutes of reeds.

31. Fifes made of deer-bones.

31a. Whistle of a deer's skull.

32. Vibrating instruments of tortise and turtle shells.

Ornaments, Dress, and Miscellaneous33. About twenty distinct articles, forming the feather headdress.

34. Combs of palm-wood, ornamented with feathers. (Plate VII. a.)

35. Necklaces of seeds and beads.

36. Bored cylindrical quartz-stone.

37. Copper earrings, and wooden plugs for the ears.

38. Armlet of feathers, beads, seeds, etc.

39. Girdle of jaguars' teeth.

40. Numbers of cords, made of the "coroá" fibre, mixed with the hair of monkeys and jaguars,—making a soft elastic cord used for binding up the hair, and various purposes of ornament.

41. Painted aprons, or "tangas," made from the inner bark of a tree.

42. Women's bead tangas.

43. Rattles and ornaments for the legs.

44. Garters strongly knitted of "coroá."

45. Packages and carved calabashes, filled with a red pigment called "crajurú."

46. Large cloths of prepared bark.

47. Very large carved wooden forks for holding cigars. (Plate VII. b.)

48. Large cigars used at festivals.

49. Spathes of the Bussu palm (Manicaria saccifera), used for preserving feather-ornaments, etc.

50. Square mats.

51. Painted earthen pot, used for holding the "capi" at festivals.

52. Small pot of dried peppers.

53. Rattles used in dancing, formed of calabashes, carved, and ornamented with small stones inside. (Plate VII. c.) (Maracás.)

54. Painted dresses of prepared bark (tururí).

55. Balls of string, of various materials and degrees of fineness.

56. Bottle-shaped baskets, for preserving the edible ants.

57. Tinder-boxes of bamboo carved, and filled with tinder from an ant's nest.

58. Small canoe hollowed from a tree.

59. Paddles used with ditto.

60. Triangular tool, used for making the small stools.

61. Pestles and mortars, used for pounding peppers and tobacco.

62. Bark bag, full of sammaúma, the silk-cotton of a Bombax, used for making blowing-arrows.

63. Chest of plaited palm-leaves, used for holding feather-ornaments.

64. Stone axes, used before the introduction of iron.

65. Clay cylinders, for supporting cooking utensils. (Plate VI. c.)7

The Indians of the river Isánna are few in comparison with those of the Uaupés, the river not being so large or so productive of fish.

The tribes are named—

Baníwas, or Manívas (Mandiocca).

Arikénas.

Bauatánas.

Ciuçí (Stars).

Coatí (the Nasua coatimundi).

Juruparí (Devils).

Ipéca (Ducks).

Papunauás, the name of a river, a tributary of the Guaviáre, but which has its sources close to the Isánna.

These tribes are much alike in all their customs, differing only in their languages; as a whole, however, they offer remarkable points of difference from those of the river Uaupés.

In stature and appearance they are very similar, but they have rather more beard, and do not pull out the hair of the body and face, and they cut the hair of their head with a knife, or, wanting that, with a hard sharp grass. Thus, the absence of the long queue of hair forms a striking characteristic difference in their appearance.

In their dress they differ in the women always wearing a small tanga of turúri, instead of going perfectly naked, as among the Uaupés; they also wear more necklaces and bracelets, and the men fewer, and the latter do not make use of so many feather-ornaments and decorations in their festivals.