полная версия

полная версияThe Boy Volunteers with the Submarine Fleet

Apparently, at regular intervals, were large ships of war, all of them in motion. Sailing vessels and steamers, carrying freight, were coming up the channel, convoyed to the open doors in this giant network which guarded the channel.

The lieutenant on the chaser backed his vessel toward the submarine and hailed the captain:

"Do you wish to remain?" he asked.

"The chances of that fellow seem to be pretty slim. I would like to see the finish of the game; but I suppose we ought to get into port as soon as possible," answered the captain.

"Then I will give the order to proceed," replied the lieutenant.

The captain nodded, and the boys started for the door.

"One moment!" said the captain. "We may still be able to see an interesting sight."

The boys rushed out of the door. Glancing up at the deck of the chaser they could see the marines aboard rushing to the side of the vessel. As they looked at the buoys it was noticed that they were silent. L'Orient was slowly backing away from the obvious location of the submerged vessel.

"They are about to throw a shell," observed the captain.

The remark had hardly left his mouth when an explosion was heard and the shell could be observed moving upward at a very high angle, and descending into the water with a vicious plunge.

No sooner had it struck the sea than it seemed to raise the surface of the water like the foaming mass in a boiling pot. The explosion was dull, vibrant, ominous.

"They are shooting another one," shouted Alfred, although he tried to suppress his voice.

"Boom!" came the sound, as he uttered the words.

The second shot struck the water not fifty feet distant from the first one.

"Do you think they will fire another?" asked Alfred.

"Probably not," answered the captain.

"What is that little boat going over there for?" asked Ralph, as one of the torpedo boats boldly advanced over the spot where the two shells had entered the water.

The captain nodded his head for a few moments before speaking.

"The shots were successful."

"I can see that now," said Ralph. "Look at the oil coming up and covering the sea."

It was, indeed, a sad sight to witness, knowing that the shots meant the death of thirty or more human beings.

"Well, I am awfully sorry for them, even if they had no sympathy for us, and didn't wait to see whether or not we were put into safety before they sent our ship down," said Alfred reflectively, as he turned and entered the conning tower.

The scene had its fascination for Ralph, although he felt the horror of it all as he stood leaning over the railing, gazing at the patrol boats which were sailing back and forth in and around the spot where the petroleum was fast covering the surface of the water in all directions.

"You can understand now, can't you, why flying machines are such good spotters for submarines?" remarked the captain.

"Do you mean the oil that comes on top of the water?" asked Ralph.

"Yes," was the reply.

"But does oil arise at all times when a submarine is submerged?" asked Ralph.

"More or less oil is constantly detaching itself from the body of the hull, at the discharge ports, and it can't be helped because all of the gas discharge ports are under water at all times, whether the vessel is running on or under the water, hence, as it moves along it will leave a trail of oil which can be easily detected by a machine in flight above the surface of the water," said the captain.

"But doesn't a machine, when it is under the water, leave a ripple that is easily seen by a flying machine?" asked Ralph.

"Yes; I was going to refer to that," replied the captain. "An aviator has a great advantage over an observer on a vessel, for the reason that the slightest movement of the surface of the sea, even though there may be pronounced waves, can be noted. If the submarine is moving along near the surface, the ripple is very pronounced, and the streak of oil which follows is very narrow. Should the submarine stop, the oil it discharges accumulates on top of the water at one place, and begins to spread out over the surface of the water and this makes it a mark for the watchful eye of the airmen of the sea patrols," answered the captain.

"I heard one of the officers at the aviation camp say that a submarine could be seen easily through fifty feet of water by an airman," remarked Alfred. "Do you think that is so?" he asked.

"I know it is possible," replied the captain.

"But why is it that when you are on a ship it is impossible to see through the water that depth?"

"For this reason," answered the captain: "if you are on a ship, and you are looking even from the topmast of the vessel, the line of vision from the eye strikes the surface of the water at an angle. The result is that the surface of the water acts as a reflector, exactly the same as when the line of sight strikes a pane of glass."

"Do you mean that the sight is reflected just as it is when you are outside of a house and try to look into the window at an angle?" asked Ralph.

"Exactly; that is one explanation. The other is this: sea water is clear and transparent. By looking down directly on the water, a dark object, unless too far below the surface, will be noted for the reason that it makes a change in the coloring from the area surrounding it, and a cigar-shaped object at fifty feet below, whether it should be black or white, would quickly be detected," explained the captain.

"I remember that Lieutenant Winston, who has flown across the channel many times, told me that he could tell when he was nearing land, in a fog, by sailing close to the water, even though the land couldn't be seen. Do you know how he was able to do that?" asked Ralph.

"That is one of the simplest problems," replied the captain. "The shallower the water the lighter the appearance to an observer in an airship. As the water grows deeper the color seems to grow greener and bluer, the bluest being at the greatest depth."

The chaser was now under way, and described a circle to the right. The captain, after saluting the officer on the bridge of l'Orient, gave the signal "Forward," and slowly the submarine sheered about and followed.

The second line of buoys appeared a quarter of a mile to the east of the one they had just left. In a half-hour the two vessels passed through the gateway and turned to the north.

"We can't be very far from England," remarked Alfred.

"I judge we are fifteen miles from Dover," replied the captain.

"Do you intend to go to Dover?" asked Ralph.

"No; there are no stations there that can receive crafts of this kind. I do not know to what point they may take us; possibly to the mouth of the Thames, and from there to some point where the vessel will be interned," answered the captain.

"How deep is the channel here?" asked Ralph.

"Probably not to exceed 120 feet," was the reply.

"Not more than that in the middle of the Channel,—half way between England and France?" asked Alfred in surprise.

"No; the Channel is very shallow," answered the captain.

"No wonder then," said Alfred, "that the submarines are having such a hard time getting through, even though they don't have the nets!"

Having passed the cordon of nets the chaser turned and slowly steamed past the submarine. The lieutenant stepped to the side of the bridge and said:

"I suppose, Captain, you can now make the pier-head at Ramsgate, where you will get a ship to convoy you to the harbor. Good luck to you! Adieu!"

The boys waved their caps in salute, as the chaser began to move, and the crew lined up to give the final goodbye.

The captain smiled and replied: "I think I have ample assistance on board; give my regards to the admiral."

"How far is it to Ramsgate?" asked Ralph.

"It cannot be more than twenty-five miles, and at the rate we are now going we should reach the head at five this evening. That will be the end of our troubles, as the naval officials will take care of this vessel from that point," said the captain.

"Well, I shall be glad of it," replied Alfred.

It was a glorious day, the sun was shining brightly, and the air, although somewhat cool, was not at all disagreeable. The boys insisted on taking their turns at the wheel, the course being given by the captain as west by north. Everything was moving along in fine shape, and Alfred was at the wheel, while Ralph was peering through the periscope, for this interested them from the moment they boarded the ship.

"Where is that steamer bound?" asked Ralph, who noticed a large two-funnel steamer crossing the field of the periscope.

"It belongs to the Australian line," replied the captain.

"Aren't we in the barred zone?" asked Alfred.

"I was about to remark a moment ago that it does not seem as though the German edict of a restricted zone makes much difference in the sailing of vessels," replied the captain.

While speaking, the submarine seemed to slow down, and the captain turned toward the conning tower. "I wonder what is up now?" he asked.

Alfred's head appeared at the door and shouted: "They don't seem to answer my signals."

The captain entered the tower, and pulled the lever, Attention! There was no response to the signal below the word. He again rang, with the same result.

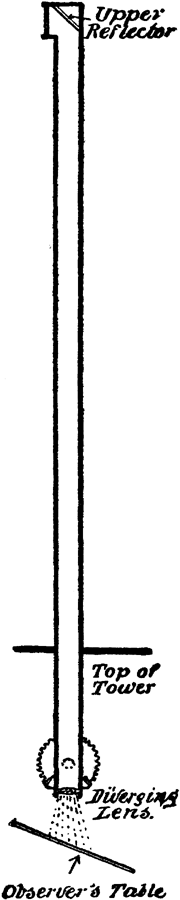

The Periscope

"I will open the hatch," said the captain.

It was quickly swung open. The sub-lieutenant appeared at the hatch with haggard face and staring eyes. "The captain has gone mad!" he shouted.

"I will go down if you want me to; I am not afraid," said Ralph.

The captain looked at him for a moment, and glanced down into the hatchway. "Why do you not obey my signals?" he asked.

The sub-lieutenant stared at the captain, but did not make a reply. "Answer my question!" shouted the captain.

The officer raised his face, threw up his hands, and fell back across the low railing, which served as a guard at the foot of the stairs.

"You may go down, and ascertain what is the matter, but use caution," said the captain.

Ralph stepped into the open hatch, and, as he did so, the captain laid his hand on his shoulder, and said: "Take out your revolver; do not trust those men for a moment, under any consideration; we know them too well."

Ralph quickly drew the weapon and held it in his hand, then cautiously descended. He passed the inert form of the officer on the rail, and not until he reached the last step did he see the doctor and the chief machinist by the side of the dynamo.

The doctor held a revolver, which he pointed straight at Ralph. "Drop that revolver!" shouted the doctor. "The lieutenant is dead, and the time fuse will soon send this ship to the bottom."

The moment he saw the revolver and heard the voice, Ralph dropped behind the stanchions to which the stairway was attached. The doctor's revolver was fired. Instantly the captain divined the cause. Without waiting for a warning cry from Ralph, he leaped into the open hatch, and saw the two men with their weapons. He covered them with his revolver.

"Come up!" he shouted to Ralph.

The latter raised up from his crouching position, with his revolver now leveled full in the faces of the two frenzied men. Before Ralph had reached the upper step both men in the hold fired, fortunately, without doing any damage.

The moment Ralph gained the deck the captain jumped out of the hatch and slammed it down.

"Now, quickly, boys; tie this rope to the railing close to the periscope tube, and arm yourself with the life preservers; there, you will find them under that couch," said the captain, as he quickly threw back the cover from the couch and handed out four preservers.

"Why do you want four?" asked Ralph, as he hastily buckled one of them around himself.

"To attach to the end of the line that you have just fastened to the rail," replied the captain.

The captain sprang out through the open door, and attached one of the life belts to the end of the line. The boys now noticed the coil of rope, which must have been more than a hundred feet in length.

"I wonder what that is for?" asked Alfred, as the captain disappeared.

"There," said the captain, as he again appeared at the door. "If she goes down that preserver will tell them where to fish for her."

"Do you think there is any danger?" asked Ralph.

"I do not know; I am not taking any chances. I have my opinion, though," replied the captain thoughtfully.

"Do you think they are going to blow up the vessel?" asked Alfred.

"No; but I am inclined to think that they have not been able to disconnect the automatic fuse, or, that the death of the lieutenant, if such should be the case, has prevented them from finding the secret key, and,–"

"That the sub-lieutenant has actually gone mad," interrupted Ralph.

The captain nodded, and continued: "Although they deserve death, still, I am not a barbarian, and shall give them a chance for their lives," and, saying this, he moved through the door, and, sighting a large steamer, gave a signal. Once, twice, three times he moved the flag from right to left. Almost immediately there was a response and two short whistles responded.

Before the great ship had time to stop, the forward end of the submarine moved upward with a violent heave, followed by an explosion that seemed to tear everything to pieces. Ralph was thrown clear of the top, and landed fully twenty feet from the side of the hull. Alfred and the captain seemed to be propelled to the stern of the ship and dashed into the waves at least fifty feet from the spot where Ralph had landed.

Ralph did not appear to be even stunned, but Alfred's head dropped lifeless on the side of the life preserver, and the captain was prompt to reach his side and support him so that his head was kept free from the water.

Ralph was bewildered at the suddenness of the affair, and, while splashing in the water, glanced first at the captain and Alfred, and then swung around to get a view of the big ship, which they had signalled. The submarine had vanished. The sea around appeared to be a mass of bubbles, and he could plainly see the petroleum which was oozing up.

Nothing was visible where the submarine floated but a single belt,—the life preserver which the captain had used as a buoy, to mark the location of the sunken vessel.

CHAPTER XIII

THE RESCUE IN THE CHANNEL

"The boat is on the way," shouted the captain, as Ralph tried to direct himself toward the captain and Alfred.

"We were just in time," said Ralph. "How is Alfred?" he asked.

"Only stunned," replied the captain. "I think he hit the conning tower as the vessel up-ended."

"Poor fellows," said Ralph, "I suppose it's all up with them."

"They are gone beyond all help. But we did the best we could," answered the captain. "Here, take this fellow first," continued the captain, addressing the officer in charge of the boat.

The boys were soon dragged in, and the officer gazed at the captain most earnestly, as he said: "Why, Captain, we heard just before we left the dock about you and two boys capturing a submarine; was that the submarine? What has happened?"

"That is a long story, but you shall hear it as soon as we get aboard. Where are you bound?" asked the captain.

"For the Mediterranean," replied the officer.

"Where is your first port?" asked the captain.

"Havre," was the answer.

"Couldn't be better," replied the captain. "Ah! I see Alfred is coming around all right."

"He seems to be breathing all right now," said Ralph.

"So they heard about our exploit?" asked the captain.

"Why, yes; the papers made quite an item about it; I think we have a copy on board," replied the officer.

As the boys ascended the ship's ladder they saw two torpedo boat destroyers crowd up alongside the ship. The captain leaned over the taff-rail and said:

"The buoy yonder marks the resting place of the U-96, late in the service of the Imperial German Navy. Please report same, with my compliments."

Alfred was taken aboard and the ship's doctor was soon in attendance. Every one crowded around and the names of the boys and the captain were soon known to all the passengers. The Evening Mail gave the most interesting account of the affair, and Ralph read and re-read the item.

An hour afterwards, when everything had time to quiet down, and Alfred had recovered sufficiently to sit up, Ralph drew out the newspaper, and, to the surprise of Alfred, read the following:

"AN EXTRAORDINARY FEAT"A SUBMARINE CAPTURED BY THREE PRISONERS"The war is a never-ending series of startling and remarkable events, the latest being the capture of a German submarine by the captain of one of the transatlantic liners and two American boys who were passengers on the captain's ship when she was torpedoed. The commander of the submarine took the captain and the two boys from the boat in which they had sought refuge, after their vessel went down in the Bay of Biscay.

"It was learned from the first officer of one of the torpedo-boats that the submarine while on its way to Germany was caught in the nets in mid-channel. While trying to disentangle itself, the chief officer of the submarine met with an accident, and, taking advantage of the situation, the captain and his two boy companions, having found a case of revolvers, held up the second officer and the crew, and imprisoned them below.

"They are now bringing the submarine to England, and we hope to be able to give more details tomorrow."

"There, what do you think of that?" ejaculated Ralph.

Alfred smiled, but a shadow came over his face, as he looked at Ralph. The latter, seeing the change, jumped up, and cried: "Are you sick?"

"No," replied Alfred wearily; "but I have been thinking of father and mother; I had a dream that I saw them standing on a dock; I wonder where they are?"

"I have some interesting news for you," said the captain, as he entered the cabin, holding a French paper in his hand.

"What is it?" asked the boys in unison.

"Boats three, four and five of our ship have reached port all right," said the captain.

"Have you heard about No. 1?" asked Alfred, as he leaned forward, and anxiously awaited the reply.

"No; but it is likely that the other boats may have been picked up by a west bound vessel, and it is not time yet to hear from the other side," replied the captain.

"But do you think they are safe?" asked Ralph.

"I do not see that they were in any great danger, as there was calm weather for at least forty-eight hours after the ship went down," answered the captain. "I understand that all but three of the boats have been accounted for."

"Have the submarines been doing much damage?" asked Alfred.

"Yes; they have sunk a great many ships," was the answer.

"Any American ships?" asked Ralph.

"No; but a number of Americans have lost their lives on vessels that have been sunk."

"Where are we going?" asked Alfred.

"To Havre," was the reply.

"I wouldn't worry about father and mother now," said Ralph soothingly.

"No, indeed; the boats were perfectly safe, and I have no doubt but we shall hear from them by the time we reach port," reassured the captain.

Ralph waited until Alfred dropped off to sleep, and then strolled up on deck and mixed with the passengers. He was kept busy telling them about the terrible hours on board the submarine, until he was tired and sleepy. Then he wended his way to the cabin and was soon asleep.

The distance from the point where they boarded the ship to Havre was about two hundred miles. Ordinarily, they would have reached port at six in the morning, but the route during the night was a slow and tedious one, for the reason that all ships along the channel route were permitted to pass only during certain hours when the war vessels acted as guides and convoys through the open lane.

Once near the zone of the nets no lights were permitted, and each ship had to be taken through by special vessels designated for this work, and, when once clear of the nets, extra precautions were taken to convoy them to relative points of safety beyond.

When Ralph awoke the next morning, and saw that it was past six, he hurriedly dressed himself, and, taking a look at Alfred, who was quietly sleeping, ascended the deck. He was surprised to see nothing but the open sea on all sides. Addressing a seaman, he asked:

"Haven't we reached Havre yet?"

"No; we may not get there until nine o'clock. We have had reports of many submarines in the mouth of the channel, and they are, probably, lying in wait to intercept steamers going to or coming from Havre," replied the man.

Pacing the deck he found many of the passengers excited at the news, although it was the policy of the officers to keep the most alarming information from them. Meeting the second officer he inquired about the captain, and was informed that he had just gone down to see Alfred. Nearing the companionway he met the captain and Alfred, the latter looking somewhat pale, and rather weak or unsteady in his walk.

"I am glad to see you looking so well," said Ralph. "Where are you hurt the most?"

"Look at the back of my head," replied Alfred. "I suppose I must have struck the railing as the thing heaved up."

The captain suddenly sprang forward and the boys followed in wonderment. Before they had time to ask any questions they were startled by a shot.

"That was a pretty big gun to make such a racket," remarked Ralph.

"It's one of the four-inch forward guns," said a seaman, standing near.

"But what are they shooting at?" asked Alfred.

"Submarine, I suppose," was the reply.

"But where?" asked Alfred.

"Don't know; haven't seen one; but I suppose the lookouts spotted the fellow," was the reply.

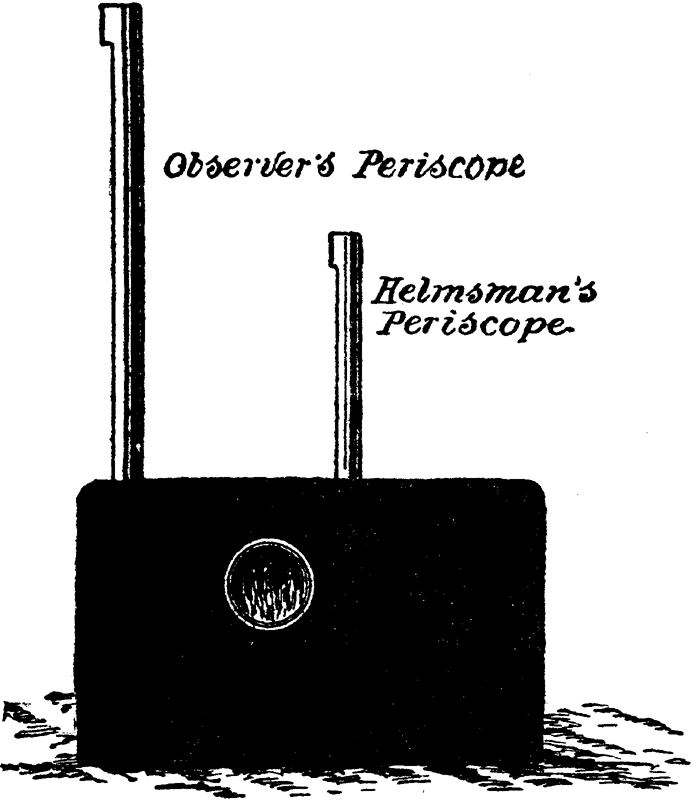

Every one now crowded forward, and gazed in the direction of the pointed glasses in the hands of the officers. In the distance nothing was visible but the conning tower and the two periscope tubes, but that was enough.

The Conning Tower, All That Could Be Seen of the Submarine

The boys moved forward, and the captain noticing them, spoke a word to the commander on the bridge.

"Come up, boys," said the captain.

Once on the bridge the captain said: "I take pleasure in introducing my companions on our little jaunt; they are brave fellows, and are made of the right kind of stuff. I think you will hear from them if America gets into the fight."

"And America is bound to get in, for we have just learned that the first American ship has been sunk without warning," said the navigating officer, as he pressed the hands of the boys.

The captain took up the receiver, which communicated with the topmast. After listening awhile, he turned to the group and said: "The sub has disappeared."

"That will mean an interesting time for us," said the captain. "I have had the same experience, but was not fortunate enough to be armed when they attacked us. Are all the vessels from England now armed?" he asked the captain commanding the vessel.

"Yes; fore and aft. We have found that but a small percentage of armed vessels have been sunk, and those which have guns at both ends are surely doubly armed," answered the commander.

The boom of the guns had brought every passenger on deck. The officers could not conceal the real state of affairs, but there was no sign of a panic. The officers did not even take the precaution to warn the passengers that they should apply or keep the life belts close at hand.

"That is the policy I suggested from the first," said the captain. "That boat must have been three miles away, at least, and a careful gunner would come pretty close to hitting the mark at that distance, and those fellows know it."

"Then why do you think the interesting or dangerous time is now coming?" asked Alfred.

"Because the safety of the ship now depends on the ability of the observers to report the moment a periscope appears in sight. If the submarine is close enough to fire a torpedo, it is near enough to be a fine target for the gunners aboard, and, as the submarine would not be likely to attempt a shot unless it had a broadside to aim at, you can see that such a position would expose her to the fire of the guns both fore and aft," responded the captain.