полная версия

полная версияThe Boy Volunteers with the Submarine Fleet

Kenneth Ward

The Boy Volunteers with the Submarine Fleet

CHAPTER I

THE OMINOUS WARNING ON SHIPBOARD

"Submarine two points to starboard, sir!" shouted a voice.

Instantly there was confusion; the captain sprang from the end of the bridge to the board behind the quartermaster and pushed a lever to the right.

"Ralph, come out quickly; the second officer has just shouted to the captain that a submarine is in sight," said Alfred, as he rushed into the reading room where Ralph was deeply engrossed in a book.

Ralph needed no second warning. Together with a dozen or more, who were in the room, he sprang to the door, and followed Alfred, who was now nearing the bridge.

"Can you see it?" asked Ralph excitedly.

"No; but they are pointing to the right; it seems as though we are turning around," responded Alfred.

"So we are," said Ralph. "There! what is that?" shouted Ralph, as he followed the direction pointed out by the second officer.

The captain gave another wrench to the wheel, and the ship straightened out on its course. All eyes were now directed to a point to the right, and astern, for the boat had described a half circle.

"Wait till I get the glasses," said Alfred, as he dived for the main companionway, and slid down the railing.

He was back in record time, followed by his father and mother, accompanied by Ralph's mother. Needless to say all were agitated, for they had been told on the morning of sailing that the trip might be a dangerous one, and it was only urgent business necessity that compelled Mr. Elton to take the risk.

"I can see something away back there, just like a trail of foam. I wonder whether that's what they are so excited about on the bridge?" questioned Alfred, as he lowered the glasses, and glanced up at the officers who were vigorously discussing the situation.

"Let me look," said Ralph, reaching for the glasses. He was silent for a few moments, then, handing the glasses to Mr. Elton, he continued: "There is something coming; see if you can make it out."

Mr. Elton gazed intently, and turned to his wife, as he said: "I am afraid that is a torpedo on the way now."

Nevertheless, he made the remark quietly; those around heard the warning, and the boys glanced at the bridge. The captain again moved the wheel, and the ship swerved.

"It is a torpedo," shouted Ralph. Every one leaned over the ship's side and waited, some with terror on their faces, others pale but calm. Two or three rushed for the companionway, and several fainted.

"It's going to miss! It's going to miss!" shouted Alfred. He turned around and waved his cap to the officers on the bridge, but they were too intent watching the submarine to notice the salutation. It was evident, however, from their actions that they had no immediate fear.

It was with a thrill that the two hundred passengers, who were lined up on the port side of the steamship, saw a foamy trail, one hundred feet distant, pass alongside their vessel, and disappear in the distance, far ahead.

"There comes another one," said a voice.

It was easy to distinguish the second peril, and it seemed to come straight and true. The ship veered slightly from its course, and breathlessly the passengers watched the trail. On, on it came. The vessel again slightly changed its course, and this time the torpedo went wide of the mark.

"Now, for the next one," said Alfred.

"Ah! we are now too far ahead, and going too fast for them. Even if the submarine comes to the surface it cannot possibly catch us," said the navigating officer, who passed along and quieted the anxious ones.

Thus, for the time being, they escaped, but the vigilance was greater than ever. They would be in the danger zone for twelve hours more.

Two and a half years previous to this time, Mr. and Mrs. Elton, accompanied by their son Alfred, Mrs. Elton's sister, and her son Ralph, were traveling through Europe, and happened to be in Germany when war was declared. The boys, together with Mr. Elton's chauffeur, were on their way to Antwerp with their car, and were pursued by the Germans as they were entering Belgium territory.

Their car was requisitioned by the Belgium government, and as the German forces entered Belgium south of Liege, they were cut off from reaching Antwerp. In the effort to make their way across the country the two boys met the Belgian forces, and were in the first battle, which was fought between the Germans and Belgians. They took part in the defense of Belgian territory with the Belgian forces, from Liege, to Louvain, Aerschott, and Malines, until the city of Antwerp was besieged, and were among the last to leave when the Belgians evacuated that place.

They were fortunate enough, however, to reach French territory with the bulk of the Belgian army, and arrived at Dunkirk, on the Channel, during that period when the British were sending over the first forces to resist the invasion of France.

The second day they visited the hangars where the British were setting up their aircraft and training the recruits for the aviation service. While approaching the grounds they were the witnesses of an accident to one of the flyers, who made a disastrous landing near them, and they were prompt enough to lift the machine from one of the men, which saved his life.

This incident was the changing point in their career, for they then determined to enter the aviation corps, if possible. Despite their efforts, they were not able to succeed, at this time, and as the father of Alfred had sent word to them to meet him in Paris, they regretfully worked their way to that city, only to learn, on arriving, that Mr. Elton was not permitted to leave Germany.

By an accidental circumstance they went to Bar-le-Duc, in eastern France, and visited the aviation grounds there. Having made themselves useful, they were favored with the privilege of making ascensions, and were instructed in the handling of the trial machines on the grounds.

On one occasion they were aloft with Lieutenant Guyon, who, owing to heart troubles, fainted while at a high altitude, and the boys brought the machine down safely. Thereafter, the lieutenant was their constant friend, and when the corps moved to Verdun they were regularly enrolled as members, and subsequently became engaged in many exciting flights. While on a scouting operation with their friend, several German machines appeared and a battle followed in which the machine was injured, and during the descent both boys were wounded.

The lieutenant was caught in the wreckage, as the machine finally plunged to earth, and within a week died of his wounds. The boys were heart-broken at his death, and after a week at the base hospital were transferred to the American hospital in Paris. After recovery they were regularly discharged from the service, and started for home.

On their way to the Channel they became interested in the artillery branch and happened to take part in the first great French drive in the Somme region and later were with the British artillery when it began its great fight against the Germans in the region west of Bapaume.

It was there that Alfred's parents and Ralph's mother learned of their whereabouts, and, through the kindly offices of the American ambassador, were permitted to visit the battery where the boys were stationed, and where they finally prevailed upon them to accompany them home.

They sailed from Bordeaux early in the morning of the same day that the events took place which we have just related. On the day of sailing the thrilling news reached France that President Wilson had given the German minister his passports, and while such an act does not, ordinarily, mean war, the strained relations between the United States and Germany made it probable that war would follow.

As stated, Mr. Elton's business compelled him to sail, notwithstanding the danger, and they now found themselves within the danger zone prescribed by the German authorities, for, as they were sailing on a ship belonging to one of the belligerent nations, they knew that it was a prey for any submarine and subject to be sunk without warning.

Although instructions of a general nature had been issued by the captain after the vessel left port, he called the passengers together immediately after the excitement attending the appearance of the submarine had died away, and addressed them as follows:

"For the next twelve or fifteen hours we shall be in the danger zone, and it is imperative that each of you should at all times carry a life belt. I impress this on you not for the purpose of creating alarm, but because I know that people become careless. The officers will give full instructions to all of you as to the way the belts should be worn, so there will be no confusion at the last moment.

"And now, another thing, which you must remember. More lives are lost through undue excitement than from the real danger, in case of trouble. We are here for the purpose of giving due warning and assistance, and every man in the ship's crew will be faithful to his duty. Do not rush about and become excited, because that unduly alarms those about you, I will give you ample warning. Five short blasts on the ship's whistle will call you to the boats. When you hear that go to your cabins quickly, seize such clothing as you have prepared for such an event, and if you have not strapped on the life belt do so at once.

"It should be the first duty of the men to aid the women and children, see that the belts are properly put on, and assist them to the deck. Once there, go as quickly as possible to the davits and await orders, for the officers and men will be there to direct and take charge of the passengers. Should the boat be so badly hit that it is impossible for all the passengers to get into the boat before the vessel goes down, the men must see to it that every one goes overboard and clears the ship's side.

"Many women will, even in this extremity, refuse to jump overboard without their husbands, but in such cases there must be no hesitancy on the part of the men. Do not argue, but push them overboard, and the life belts will hold them in position in the water until the waiting boats can rescue them. There will be no danger of drowning under those conditions, but be sure to jump as far from the vessel as possible."

It was not such a speech as tended to relieve nervousness, but it certainly made every one within hearing very thoughtful. Women, and men, as well, turned white, and many of them timidly examined the tiny life belts which were handed out.

"It seems that we get into trouble wherever we go," said Alfred, not in a spirit of alarm, however, but more because he felt a deep concern for his father and mother.

"Oh, Ralph, isn't this terrible!" said his mother, as she came forward.

"It certainly is; but this is something like the experiences we have had for over two years, and it doesn't make it seem so bad;—do you think so?" he added, addressing Alfred.

"I wouldn't be at all worried, Auntie," responded Alfred. "Here comes mother; I hope she is not broken up or worried."

"No," replied Mrs. Elton. "It is dreadful, but it is no worse for us than for others. I am glad the captain spoke as plainly as he did. We must understand and do our duty."

"Now, Mother, you and Auntie go to the ladies' room and stay there. If anything happens we will know where to find you," said Ralph.

"But I want you to come and stay with us," replied Mrs. Elton.

"We cannot do that," replied Alfred. "We have fine glasses and every one should be on the watch. It takes a great many eyes to see in all directions."

"Alfred is right," said Mr. Elton. "I will remain with you; but do not be alarmed for the present."

"Wait until I get my binoculars," said Ralph, as he rushed down to the cabin.

He was up at once, and together they ran forward to the bridge, as the second officer descended.

"Can we be of service to you in any way?" said Alfred, pointing to their glasses.

"Indeed, you can," said the officer.

At that moment the captain, leaning over the rail of the bridge, shouted: "Come up, boys; those are the right kind of weapons. We ought to have dozens more of the same kind."

The boys fairly stumbled up the steep, narrow ladder that led to the bridge.

"At your service," said Ralph.

The captain smiled, as he said: "Take positions at the end of the bridge."

The boys walked across to the other side, and Ralph elevated his glasses.

A moment later the captain, in his walk to and fro, stopped before the boys. "You have evidently had occasion to use the binoculars before, but probably not while at sea," he observed.

"No," replied Ralph; "we used them in flying machines and while serving in the artillery, but this is really the first opportunity we have had to use them on shipboard."

"Then a little instruction will be of service to you and to all of us," said the captain. "I noticed that you were sweeping the sea to the rear. That is not necessary, for at our speed a torpedo boat would not be able to catch us. All your time should be devoted to scanning that quadrant from straight ahead to a point but a little astern of your left quarter, as it is from that section, and the corresponding section on the right side of the vessel that we expect the enemy; do you understand what I mean?"

"I think so," replied Ralph. "But suppose a submarine should be well ahead of us and submerge, and then wait until we have passed. In that case couldn't it again come up and send a torpedo into the stern of the ship?"

"That might be possible, but not probable. A submarine is absolutely in the dark when completely submerged," said the captain. "It must come to the surface sufficiently near to bring its periscope out of the water, and that would reveal its presence to us. It would be a pretty hard job for a navigator in a submarine to calculate when the boat had passed sufficiently near to know the opportune time to come to the surface and give us the shot."

"But couldn't they come near enough to take a chance? They might come up 500 feet away or 2,000. At either distance they could land a torpedo, couldn't they?" asked Alfred.

"Quite true; but the submarine might not know whether we were armed or not, and it would not take the risk of exposure in that reckless manner," replied the captain.

"But we are not armed, are we?" asked Ralph.

"No; our guns will be ready for us on the return trip," answered the captain. After a moment he continued: "Let me also give you a hint as to the particular manner of using the glasses to get a correct view. Do not attempt to take in the entire field at one sweep. Sight at a point near the ship, say at a distance of a quarter of a mile; then slowly raise the glasses so that your view grows more and more distant and finally the focal point reaches the horizon. Then turn a point to the right or to the left, and bring down the forward end of the glasses until the view is again concentrated on the point nearest the ship."

"That is something like making observations on a flying machine," replied Alfred, "only in that case the glass is held stationary, as the machine moves along, and in that way objects can be seen much better than by sweeping it around continuously. We learned that from Lieutenant Guyon."

"Quite true; I see you are well qualified to observe. But to continue: after you have thus made the first observation as I have explained, the glasses should be held horizontally to take in the view at the horizon, and then swept around at that angle to the right or to the left, depressing it at each swing. That is called sweeping the sea."

"I know two men who have glasses," said Ralph. "Shall I get them?"

"Yes, if you can; this is the kind of service which is appreciated," said the captain.

Ralph sprang down the ladder, and ran along the deck. He was absent for some time, but soon appeared with two men.

"Come on," said Ralph, as he ascended the ladder. The men hesitated for a moment, and followed, as an officer appeared and invited them to come up.

CHAPTER II

THE TORPEDOED SHIP

During the next hour or more every field glass on board ship was put into use, and many were the weary arms that used them until the luncheon hour arrived at one o'clock. The captain, knowing how trying the constant watching must be to civilians who are not used to this work, appointed two watches, so they might relieve each other every hour.

The boys went to the dining room, and as Mr. Elton and his family sat at the captain's table, the latter took occasion during the meal to refer to Ralph and Alfred's services on the bridge in commendatory terms, which was greatly appreciated by their parents.

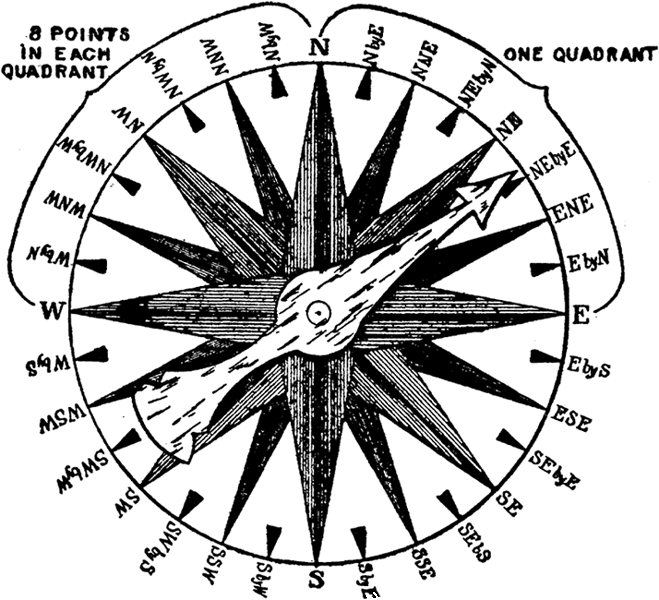

"I am curious to know," said Ralph, "what the officer meant when he said 'two points to starboard.'"

"That is explained in this way," replied the captain. "The compass is divided into thirty-two points, or eight points in each quadrant."

"I remember you spoke about a quadrant when we were on the bridge. What is a quadrant?" asked Alfred.

"I should have said, in the beginning, that the compass is divided into four parts, one line running, we will say, east and west, and the other line north and south. In that way there are four cardinal points. You will understand, therefore, that from the north cardinal point to the east cardinal point, which represents one quadrant, are eight points, and so on, from the cardinal point east to south, are eight more points," responded the captain.

"Then when the officer said 'two points to starboard,' did he mean two points from one of the cardinal points?" asked Ralph.

"No, he had reference to two points from the line ahead, or for the time being, he took the line upon which we were traveling, as one of the cardinal lines, and when he said two points he described a line which was just one-fourth of the distance around the circle or quadrant to the east," answered the captain.

"Then we might say that the keel of the ship is one of the cardinal lines, and the bridge, which runs across the ship is the other line?" asked Alfred.

"That is a very homely and plain way of putting it," replied the captain.

An hour thereafter, while the boys were on the bridge, they noticed the first signs of excitement on the part of the officers. A message had been handed the captain a few moments before. Of course, all were curious to know the news it contained, but no one seemed to be bold enough to ask any questions.

The Points of the Compass

As the second watch appeared at the bridge the boys descended and rejoined their parents. A voice was heard outside summoning the passengers on deck. They were ranged along the deck house, and the second officer appeared.

"I wish to make an announcement, and give further instructions. In order that there may be no confusion, in the event the enemy should attack us and compel the passengers to take to the boats, I am going to assign places to all of you, so that the moment you hear the five bells you will know where to go, ready to man the boats. Now, notice the numbers on the boats, which you see are swung out on the davits ready to be launched. Be particular to note where your boat is located, and its number. When you come up the companionway from your cabin, fix in your mind whether your own boat is on the right or on the left side; some are liable to become confused in coming up.

"Boat No. 1; Mr. Elton, how many are in your party?"

"Five," was the answer.

"Then three more will be assigned; Mr. Wardlaw, wife and daughter; that will complete the first boat. No. 2," continued the officer, as he made the assignments. This was continued until the entire list was completed.

Four seamen were then designated for each of the boats, and the steward was directed to prepare emergency food for the different boats, and by direct orders the food was actually placed in the boats.

It was really with a sigh of relief from the suspense that the boys awaited the signal for their term of duty on the bridge. They were in their places instantly, and seized the glasses. It was now four o'clock in the afternoon. They were moving toward the setting sun. The sky was free of clouds and the ocean fairly smooth. It was an ideal sea for observation. The boys were on the port or left side of the ship.

"Ralph," said Alfred under his breath, as he moved toward Ralph, and laid his hand on his arm, without lowering his glasses, "look over there! there!—two or three points,–"

"I see it,—yes,—Captain, what is that, a half-mile off to the left?" interrupted Ralph.

The captain shot a glance in the direction indicated. "Three points to port!" he said, as he sprang to the wheel and gave a signal to the engineer. As he came back to the point of observation, he said:

"Young eyes are very sharp. You have beaten the watch on the top mast."

The officer in charge of the telephone beckoned to the captain. The latter rushed over, and the boys saw him nod.

"How far are they from us?" asked Alfred.

"Two miles," was the answer.

"Two miles!" said Ralph in astonishment. "Why, I thought I was stretching it when I said a half mile."

"To be more exact, the range finder in the crow's nest makes the distance 10,980 feet," said the captain.

"Well, they can't hit us at that distance," said Ralph, "can they?"

"No; we can easily avoid that fellow, but he may have appeared as a ruse," said the captain, glancing to starboard, with an anxious air.

The first officer standing near, although intently watching the submarine in the distance, remarked: "It is now the custom for two or more of the undersea boats to operate in unison; the one we are now looking at may be a decoy."

"What do you mean by 'decoy'" asked Ralph, in astonishment. "Is it likely that they would expect us to steer right into them?"

The Submarine Decoy

"No; their idea is to have one of the submarines show up in front, knowing that the intercepted vessel will turn to avoid it. Then the other submarine, with nothing but its periscope above the water, and on the other side of the sailing course of the ship, will be in position, the moment the turn is made, to deliver the shot. That is why the captain has gone to the other side, as you will notice the vessel is now going to starboard," said the officer.

The ship had now turned so that it was broadside to the distant submarine. Not only its conning tower was now visible, but a long black object fore and aft could be plainly observed.

"Three points to port!" shouted the captain.

The quartermaster swung the wheel around, and the ship seemed to heel over, so suddenly did the rudder act.

"One point to starboard, and full speed ahead!" was the next order from the captain.

It seemed that the order had no more than been executed than he again sang out:

"Two points to port!"

"What is that for?" asked Alfred.

"He is zig-zagging the ship through the sea," replied the officer.

"What for?" inquired Ralph.

"There is another submarine three points to starboard astern."

"Then,—then the captain,–"

"Yes; the one behind us is near enough to reach us if we keep on a straight course, but the captain has manoeuvered so as to bring him directly in our wake, and continually changed the target so that the submarine cannot aim with accuracy," interrupted the officer.

The passengers on the decks below did not need to be told that something unusual was happening. The changing course of the ship, the unusual activity on the bridge, the leveling of the glasses to the port side and to the stern by the different groups, were sufficient warnings of the presence of the dread monsters.

The submarine on the port side was now coming forward with all the speed it possessed, and again the captain turned the ship another point to starboard. The funnels were belching smoke, and sparks flying from the top. The engineers were putting on forced draft and the ship seemed to be trembling as it shot through the smooth sea. It was an ideal condition for the launching of a torpedo.