полная версия

полная версияThe Boy Volunteers with the Submarine Fleet

"Torpedo coming on starboard side!" shouted a voice.

Every one now rushed to the right side of the bridge. There was a shriek below. From an unexpected quarter the third submarine's periscope was visible, and a foamy trail, straight as a mark, began to lengthen out toward their vessel.

"Reverse! Reverse engines!" shouted the captain. The order was executed, but too late. The trail came nearer and grew broader. Some of the passengers put their hands over their eyes, others stood like fixed statues. The captain placed his hand to his brow, but quickly turned.

"Order the men to the boat!" he said in a quiet voice, as he stepped forward and seized the handle of the boat's whistle.

No sooner had the order been given when a terrific crash followed. The bridge seemed to have been seized with a giant hand and it vibrated with an intense force. A hundred feet from the stern of the ship a great mass of water shot upward and fragments of the deck were hoisted up and scattered around.

The ship at first swayed to port and then quickly swung back to starboard, but did not again roll back to port. The captain shook his head. There was a perceptible list in the position of the ship.

"Take your position in the boats!" he shouted to the men on the bridge, and as he did so he quickly pulled the lever,—one, two, three, four, five.

By the time the last blast sounded the seamen were at the boats assigned to them. The engines had stopped. The passengers, all except those who had fainted, had left the deck. Ralph and Alfred made a dash for the waiting room. Their parents were not there. Down they went to the cabins, passing on the way the crowded hallways and the unutterable confusion which resulted from the order to hurriedly leave the ship.

They found their parents in the cabin, and, due to the forethought of Mr. Elton, the lifebuoys had been adjusted, and their valuables secured beforehand. Others, however, were not so fortunate. Across the way were several women and children.

"Let me help you," said Alfred, as he entered the first cabin. "I will take care of the baby," he remarked, as he picked it up, while the mother was almost frantic.

"I will take the other one," shouted Ralph.

"We can't stop here another minute," said Alfred. "Do you see how the ship is leaning over?"

"Come on, Mother," cried Ralph; "follow us or we may not be able to go up the stairs."

Alfred crowded close behind Ralph, and Mr. Elton assisted the two women along the passageway. All arrived on deck, the boys with the two children in their arms.

"Where is No. 8?" "I can't find No. 9," said another. "What has become of the girl?" shrieked one; "Are we going to turn over?" asked a trembling voice. The officers were going to and fro, mingling with the passengers.

"What is your boat number?" asks one officer. "This way; that is the place you are assigned to."

Mr. Elton and his party reached No. 1 without accident, and all but the boys were safely placed in the boat.

"Come on, boys," said Mr. Elton. "But where is the mother of the children?" he asked, as he saw the boys were unaccompanied.

"Take the baby," said Alfred, as he passed it to his mother.

Ralph handed the little girl to one of the seamen, and sprang after Alfred. There was now a dangerous list, and Mrs. Elton noticed it.

"Is there any danger if our boys go below to the stateroom?" she asked the petty officer, who was holding the rope connected with the tackle of their boat.

"She'll have to sway over a great deal further to go down," he remarked.

This comforted her for the moment. Passengers were still coming up from the companionways; some were being dragged along, and others acted like drunken men and women. It was a terribly trying sight.

An old man shambled forward as he emerged from the cabin door, glanced along at the filled boats held in the davit, tried to speak, and fell headlong on the deck. A surgeon near by rushed up, turned him over, felt of his heart and pulse, shook his head, and drew the body close up to the side of the cabin wall. Then the officer made a search to ascertain the name of the man, and extracted papers from his pockets.

Meanwhile, the boys had not returned, and the ship was turning over on its side more and more.

"Launch the boats!" ordered the captain.

"But our boys! our boys!" shrieked Ralph's mother, but as she arose she was forcibly restrained. The captain did not hear, and at the command the boats went down. Even then a half-dozen passengers emerged from the door too late, and one of them, notwithstanding the warning, was without a life belt.

The ship's deck was now at an angle of fully thirty degrees,—as steep as the ordinary roof. Those emerging from the cabin on the port side could not maintain a footing, but were compelled to slide down to the side railing. This was the situation when Ralph and Alfred reached the door which led to the deck from the companionway. They were carrying the woman whose children they had rescued, as she was in a frenzy, and struggled with the boys. The moment the inclined deck was reached Alfred said:

"See that she goes overboard, and I will go down for that little girl," and he crawled back into the ship.

Ralph finally succeeded in loosening the woman's hold, and together they slid down the deck. The woman was now uncontrollable. She threw her arms about wildly, and cried for her children. Ralph pointed to the boats below, but this did not quiet her. Taking advantage of the moment when both hands were free, Ralph, by a terrific effort, pushed her across the railing, and, with a loud shriek, she shot downward.

Ralph looked around, and caught a momentary sight of his parents in the boat below. Mrs. Elton was calling for Alfred. Ralph nodded his head and tried to crawl back up the inclined deck, but it was useless. An arm then appeared through the door opening, then a head, and he knew it must be Alfred.

"Can't you help me up?" shouted Ralph.

Alfred disengaged himself and extended his body down along the deck. This enabled Ralph to seize hold of his legs and draw himself up into the doorway.

Once there he saw the trouble that Alfred had to contend with. Lying half-way up the stairs was a poor cripple, half dead with fright, and the little girl, not much better. Laboriously, he had assisted, first one and then the other, and was about exhausted when Ralph came to the rescue.

CHAPTER III

PRISONERS ON BOARD OF A SUBMARINE

The captain was still on deck, together with the first officer, both of them being at that time on the upper side of the vessel. They made the most careful examination of the staterooms and searched every corner to be sure that no one lingered behind. Coming forward they witnessed the struggles of the boys with the cripple and the girl, but the ship was now too far over on its side to permit them to render assistance.

The cripple was soon brought to the door, and, without ceremony, pushed down the incline. The little girl followed, but before the boys could reach the railing the poor cripple slipped over the railing and disappeared. The boys held the child aloft for a moment, and then dropped her into the waves.

"Jump as far as you can!" shouted the captain.

Ralph placed a foot on the railing, and, looking back at Alfred, said: "Here goes! Come on!"

Both boys landed at almost the same time. The little girl was aroused by the cold water, and was wildly floundering about, but the cripple lay upon the surface of the water, with face upturned, limp and still. They glanced about; where were the boats? They could not be far away.

"I am afraid he's done for," said Alfred, as he glanced toward the cripple.

"Well, we might as well stay near him; he might be all right," replied Ralph.

"Move away from the ship quickly," said a voice in the water, not far away.

It was the captain. He was the last one to dive, after he had seen every passenger safely off the ship.

"We have no time to lose; take care of yourselves; I will help the little girl," he continued, as he threw the child on his back, and began to strike out.

The sea had been calm up to this time, but no sooner had the captain ceased speaking than a tremendous wave almost engulfed them; they seemed to be carried up, and then were forced down by a giant swell. Another wave followed and then another, until, finally, the oscillations of the waves seemed to be growing less and less.

"Where is the ship?" cried Alfred.

"She's gone down; that's what made the waves," said the captain.

The cripple's hand was raised up, and his eyes began to roll.

"This fellow's all right, after all," said Ralph. "I'll help him. I wonder where the boats are?"

The sun, which was going down while all this had been taking place, had now disappeared, and there was that gray, lead-like appearance on the waves that comes just before twilight.

"Keep up your courage, boys; we shall soon have plenty of boats looking for us," said the captain.

Within less than a minute thereafter two boats could be seen bobbing up and down not far away, heading straight for those in the water. Ralph was the first one caught by the strong arm of a seaman, and then the little girl, now fully recovered from her fright, received the care of a woman in the boat.

Alfred assisted the cripple into the other boat, and the captain ordered all the passengers transferred to the boat which had just come up.

The boys then noticed that only three seamen remained, together with the captain and first officer.

"You may remain with us," said the captain, addressing Ralph and Alfred.

This was, indeed, a compliment to them, which was appreciated.

"I know father, mother and auntie are all right," said Alfred. "Do you think they saw us get off?" he added anxiously.

"They were standing by when you jumped, but when the ship made the last lurch, just before she went down the seamen knew that they must pull away to avoid being sucked under. It might have been too dark for them actually to have seen you get away, at the distance they were from the ship, but I don't think they will expect to see us before morning."

"Why, do you intend to stay here all night?" asked Ralph.

"No, but each boat crew has had instructions to make for the nearest port, as rapidly as possible," replied the captain.

"Where are we now?" asked Alfred.

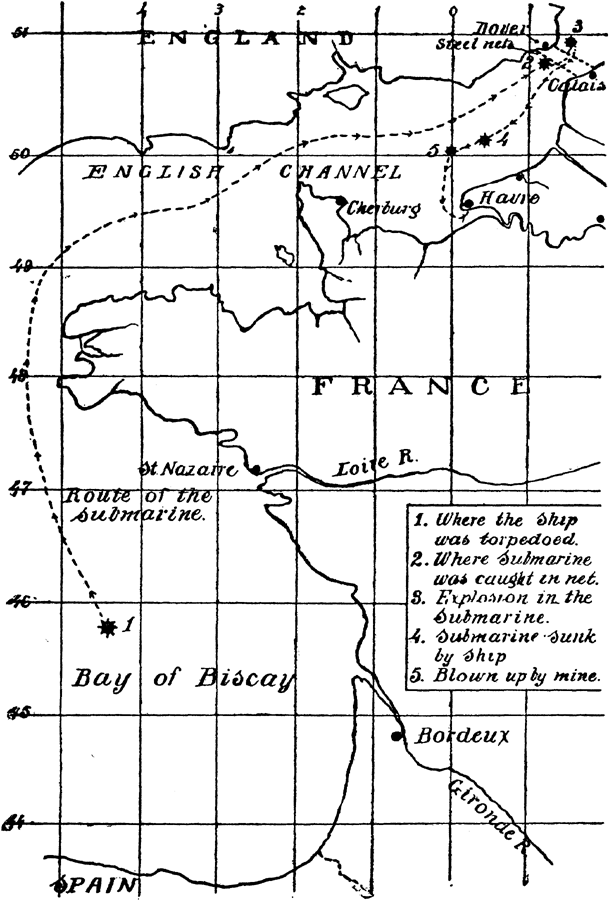

"In the Bay of Biscay, about one hundred and fifty miles from the nearest land," answered the captain.

"How long will it take us to reach land?" asked Ralph.

"Possibly two days, or more; that depends on the weather and the conditions in the bay. This is the most turbulent body of water anywhere on the Atlantic coast line, but it has been remarkably smooth during the past twenty-four hours," answered the captain.

"What is the name of the place that we are heading for?" asked Ralph.

"St. Nazaire; a French town at the mouth of the river Loire," was the reply.

It was now quite dark, and a haze prevented the occupants of the boat from making any observation of the stars, hence the sailing, or rather, the rowing, had to be conducted by compass entirely, the order being given by the captain to steer east by north, a term which indicates that the course was exactly two points north of a line running due east and west.

Three miles an hour at the outside, would be considered good speed. Sails would have been useless without a wind, and there was not the slightest breeze, but about midnight there was an apparent rocking in the little boat that indicated a wind. Occasionally, there would be a jerk, as the boat would be thrown from one side to the other. The captain was awake and alert, but the boys were lying in the bottom of the vessel near the stern.

It was a trying, weary night, and when the sun arose the sea was one panorama of short, choppy waves. The seamen were tired with rowing, and it was evident that no great effort was being made to hurry the boat along.

"It does seem to me that the sun is coming up on the wrong side this morning," remarked Alfred, as they were partaking of the food prepared and stowed in the boat's lockers.

"I imagine you are turned around somewhat," replied the captain. "The wind is now coming from the east, and you see the sun almost ahead of us. We are being carried west faster than the rowers can take us eastward, hence we are practically standing still, or rather going back, and they are now merely holding the boat so as to give us steerage way and prevent us from going into the troughs between the waves."

"Have you sighted either of the other boats?" asked Alfred.

"No; but one of the men observed a light at two this morning, three points to starboard, which was, possibly, one of our companions, but since that time we have searched the seas fruitlessly," answered the captain.

"I don't know why it is that if all of the boats steer to the same point that they should be scattered in this way," said Alfred. "Can you explain it, Captain?"

"It would not be so if in the open sea, or in mid-ocean; there they would be likely to keep together, or not separated more than three or four miles; but it is quite another thing in this great bay," replied the captain.

"Why should it be different here?" asked Ralph.

"If you will take a map of the western part of Europe, you will notice three great projecting headlands, or points on the western shore of the continent of Europe, namely, Iceland, in the north, and the Spanish peninsula in the south. Midway between you will notice Ireland and the British Isles. The great Gulf stream comes down from the north, passes Iceland, that is one branch, hugs the coast of Ireland, and strikes the point of land which projects out northwesterly from the main Spanish land, so that a sort of maelstrom is set up in the bay."

"How far are we from that point of land?" asked Ralph.

"About two hundred miles northeast; and I may also say that we are just about in the middle of the Bay of Biscay, and at that point where the sea is always more quiet than at any other part," answered the captain.

"Ship to starboard, sir," sang out the forward watch.

The captain turned to the right and, after a brief glance, lowered his hand. The boys looked at him in wonder. Evidently the sight of the vessel did not give him pleasure. It was a low-lying craft, with two short masts.

"That looks like a submarine," shouted Ralph.

"You are right," replied the captain.

The submarine was coming forward rapidly, and within fifteen minutes it was within hailing distance. They now had an opportunity to examine the ugly thing with the long black back and the conning tower midway between the ends.

"Are those the periscopes?" asked Alfred. "I didn't know they carried two of them."

"That is the practice now," said one seamen.

The submarine came straight toward them, then sheered off and stopped alongside less than thirty feet from the boat. One of the seamen tossed a rope, which was grasped by a marine on the undersea boat, and in that manner they were drawn close up to the side of the submarine.

An officer now came forward, and in French invited the captain to step aboard. There was a broad smile on the officer's face, as he recognized the captain of the vessel which they had torpedoed the night before. With a respectful bow he requested the captain to turn over the ship's papers. The captain was, of course, powerless, but he refused to do so on the plea that he did not have them with him.

"Search the boat!" commanded the officer to several of his crew.

The captain was about to go back to his boat when the officer remarked:

"We prefer the pleasure of your company for the present, sir."

The captain folded his arms, and stood straight before the officer, as two marines jumped into the boat, and began the search. Eventually, a leather case was found, on which was inscribed the ship's name. It was tossed up to the officer, who, after receiving it, entered the conning tower, where he remained for some time.

When he reappeared he said: "I shall have to detain you," and, glancing down into the boat, continued: "The two young men in the stern will also come aboard."

The boys were astounded at this new turn of affairs. Slowly they arose, and stepped on the narrow platform which projected out from the side of the submarine.

"There may be some reason why you should wish to detain me, but there is no excuse for making these young men prisoners; they are Americans returning home, and cannot be considered as belligerents," said the captain.

The lieutenant looked at the captain and turned his gaze on the boys a few moments before replying: "In what business were they engaged while on the continent?"

The captain started slightly, while the officer toyed with his mustache, and peered at the boys.

"We haven't engaged in any particular business on the continent," said Ralph.

"No; flying isn't engaging in any business, is it?" inquired the officer.

"Well," said Alfred, "we took part in the Red Cross service, were with the infantry, served a time with the flying corps, then had a little experience with the transportation service, helped them out in the artillery, and did the best we could everywhere we went, if that's what you wish to know."

The officer gave the boys a cynical glance, and nodded to one of the marines. The latter stepped forward and began searching the boys, Ralph being the first to undergo the ordeal; several letters, a few trinkets, a knife and a purse, containing all the boy possessed, were removed. The coat when thrown back revealed a cross, suspended by a ribbon, the decoration which had been bestowed on the boys after their last flight at Verdun.

Alfred handed over the contents of his pockets. The German officer glanced at the medals, and made another motion. The seamen then pushed them into the conning tower and the boys saw a narrow flight of stairs to which they were directed, the captain following.

Down into the bowels of a submarine! A warm, peculiar, oily odor greeted them as they descended, but the air was not at all unpleasant and breathing was easy. Glancing about they saw confused masses of mechanism, tanks, pipes, valves, levers, wheels, clock-faced dial plates and other contrivances, all huddled together, with barely room to pass from one place to another. Electric bulbs were everywhere visible, lighting up the interior.

Suddenly there was a slight tremor in the vessel, indicating that some machinery was in motion. Once at the bottom they stood there until the seaman stepped forward and opened a small door through which there was barely room to pass, and he motioned them to enter. They did so, and found themselves in a compartment which did not seem to be more than five by six feet in size, and even in this small space mechanism was noticed. The moment the door closed they were in total darkness.

"This is a nice place to get into," said Ralph.

"I wonder if they are going to keep us cooped up like this without a light?" said Alfred.

After an interval of ten minutes a rumbling was heard, which continued, a rhythmic motion followed in unison with the sounds generated by the machinery.

"That is the propeller," said the captain.

Voices were heard occasionally, but words could not be distinguished. Confined as they were the air seemed to be pure and in abundance at all times, and while there was not the faintest signs of closeness, there was an eternal monotony,—an existence in which there was nothing to do but breathe and think.

How long they were thus confined, without a single thing to break the stillness, they could not conceive. It seemed that hours had gone by, during which time there was nothing to disturb them, except the one steady whirr, broken occasionally by some remark by one or the other.

Then came an unexpected hum of voices; the machinery seemed to stop for a moment, and when it was again continued it had a different melody. The wheels, if such they were, seemed to turn with smoothness, and they felt a sudden inclination in the seats on which they were sitting.

"What do you suppose has happened?" asked Ralph.

"The electric mechanism has been hitched to the propeller, and, if I am not mistaken, we are going down," said the captain.

"It did feel as though the forward end dipped down a moment ago," said Alfred.

Another wait for a half-hour, and then a most peculiar sound reached their ears. Simultaneously, the ship seemed to stop and go on. Again voices were heard, and the same reaction in the hull of the submarine was felt, accompanied by the dull noise, as before.

"They have just fired two torpedoes," said the captain.

CHAPTER IV

THE TERRORS IN THE DARK ROOM OF AN UNDERSEA BOAT

Imagine yourself locked in a compartment, barely large enough to stretch yourself out straight, in a ship under the sea, in total darkness, knowing that should any one of the hundreds of things within that ship go wrong, it would mean a plunge to the bottom of the sea, beyond the help of all human aid.

The danger to them was just as great while on the surface of the water, for the guns mounted on most vessels at this time, would make the submarine a legitimate prey. One shot would be sufficient, for ingenuity has not yet found a way to quickly stop a leak in a submarine. Such a vessel, when once struck, dare not dive, for that would quickly fill the interior of the vessel with water.

It must, in that case, remain afloat, subject to the hail of shot which must follow, their only salvation in that event would be to hoist the white flag. Few, if any submarine commanders have done so, and even should that occur, it would not prevent the hull from being riddled before the fact could be made known. The three-inch guns mounted on most of the merchantmen, with an effective range of three miles, could tear the weak hull of a submarine to pieces at a single shot, and all would be sure to go down before help could arrive from the attacking steamer.

"The machinery seems to go very slow now," remarked Ralph.

"They may be cautiously coming to the top," replied the captain.

"Did you hear that peculiar noise?" said Alfred, as he laid his hand on the captain's arm.

"That was plainly a shot from a ship," said the captain.

"Do you think we could hear firing through all this metal?" asked Ralph.

"Much easier than if we were on deck," answered the captain.

"Why do you think so?" asked Alfred.

"Because water is a better conductor of sound than air," was the reply.

"Do you mean that we can hear it better than if the sound came through the air?" queried Alfred.

"The sound can be heard not only much plainer, but also much sooner than through the air," answered the captain.

"I think we are going down again," remarked Ralph.

"No doubt of it," answered the captain quietly.

"Do you think they have hit us?" eagerly inquired Ralph.

The captain did not reply. Alfred reached his hand forward and grasped the captain's hand. "You needn't fear to tell us if you think we are going down for the last time."

"You are a brave boy!" said the captain. "I do not know what to answer. I have never been on a submarine when it was struck by a bullet; but it seemed to me as though something struck our shell, and if it did there is no help for us, for the devils would gloat on our misery, and would not think of liberating us, to give us a chance for our lives."

Fifteen minutes elapsed before the captain continued: "This gives me some hope."

"What is it?" quickly inquired Ralph.

"We are still on an even keel," was the answer.

"Does that mean that we are safe?" asked Alfred.

"Yes, if the shell of the submarine had been pierced, and we were really going down it would not be long before the hull would lose its equipoise and turn around, or it might stand on end, due to the distribution of water throughout the interior," was the reply.

"I understand now," said Alfred. "You think we are still floating, but do you think we are on the surface?"

"We are, undoubtedly, submerged, for it is evident that the smooth motion of the propeller comes from the electric motors and not from the internal combustion engines, which are used solely while running on the surface," remarked the captain.