полная версия

полная версияA Company of Tanks

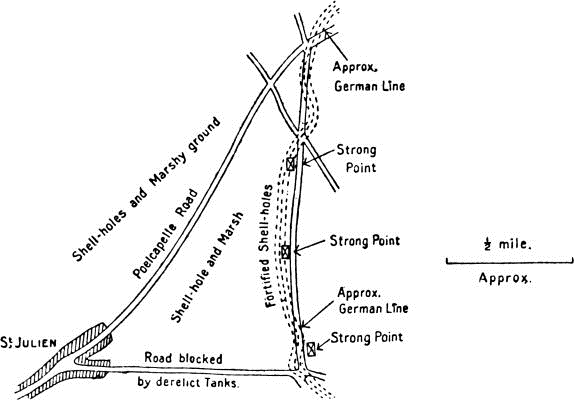

On the front which concerned my battalion we had driven the enemy back over the Pilkem Ridge into the valley of the Hannebeek, and at the foot of the further slopes he was holding out successfully in a number of "pill-boxes" and concreted ruins. St Julien itself was ours, a little village along the main road to Poelcapelle at the crossing of the stream. Beyond, the ground was so ravaged with shell-fire that it had become a desert stretch of shell-holes, little stagnant pools, with here and there an odd hedge or a shattered tree. The enemy defences, which consisted of strong points skilfully linked up by fortified shell-holes, overlooked the opposite slope, and our guns were compelled to remain behind the shelter of the Pilkem crest.

A few of the strong points on the west of the main road, notably the "Cockroft," had already been cleared by a mixed company of "G" Battalion in a successful little action. The tanks, using the roads for the first time, had approached the forts from the rear, and the garrisons in their panic had surrendered almost without a fight.

Ward's company had made a similar attack along the road running east from the village. On the day before the action the enemy had spotted his tanks, which were "lying up" on the western slope of the Pilkem Ridge, and had attempted to destroy them with a hurricane bombardment of 5.9's; but a tank has as many lives as a cat, and only three or four were knocked out, though the flanks of the remainder were scarred and dented with splinters.

The action itself was typical of many a tank action in the Salient. The tanks slipped off the road and became irretrievably ditched, sinking into the marsh. They were knocked out by direct hits as they nosed their way too slowly forward. One gallant tank drew up alongside a "pill-box," stuck, and fought it out. We never quite knew what happened, but at last the tank caught fire. The crew never returned.

The road out of St Julien was littered with derelicts, for tanks of another battalion, endeavouring by that road to reach another part of the battlefield, had met their fate.

It was therefore with mixed feelings that I received the order to get ready a section with a view to co-operating with the infantry in an attack on the same front.

I had already moved my company without incident to the Canal, where they remained peacefully, camouflaged under the trees.

I selected for the enterprise Wyatt's section, which, it will be remembered, had fought on the extreme right at the first battle of Bullecourt. His four tanks were at this time commanded by Puttock, Edwards, Sartin, and Lloyd. It was a good section.

First, we consulted with the G.S.O.I. of the Division, which lived in excellent dug-outs on the banks of the canal. The infantry attack was planned in the usual way—the German positions were to be stormed under cover of the thickest possible barrage.

We were to attack practically the same positions which Ward's company had so gallantly attempted to take. The direct road, perhaps luckily, was blocked by derelicts. A rough diagram will make the position clear:—

It will be obvious that, since my tanks could not leave the road, and the direct road was blocked, it had become necessary to use the main road across the enemy front and attack the strong points down the road from the north. Further, the tanks could not move out of St Julien before "zero" in case the noise of their engines should betray the coming attack. We were reduced, in consequence, to a solemn crawl along the main road in sight of the enemy after the battle had commenced.

We decided boldly to spend the night before the battle at St Julien. We had realised by then that the nearer we were to the enemy the less likely we were to be shelled. And the idea of a move down the road into St Julien actually on the night before the battle was not pleasant. No margin of time would be left for accidents, mechanical or otherwise.

Cooper, Wyatt, and I carried out a preliminary reconnaissance into the outskirts of St Julien on a peaceful day before coming to our decision. The sun was shining brightly after the rain, and the German gunners were economising their ammunition after an uproar on the night before, the results of which we saw too plainly in the dead men lying in the mud along the roadside. Wyatt made a more detailed reconnaissance by night and planned exactly where he would put each tank.

On the night of the 25th/26th August Wyatt's section moved across the Canal and up along a track to an inconspicuous halting-place on the western side of the crest. It was raining, and, as always, the tracks were blocked with transport. An eager gunner endeavoured to pass one of the tanks, but his gun caught the sponson and slipped off into the mud. It was a weary, thankless trek.

On the following night the tanks crawled cautiously down the road into St Julien with engines barely turning over for fear the enemy should hear them. The tanks were camouflaged with the utmost care.

The enemy aeroplanes had little chance to see them, for on the 27th it rained. A few shells came over, but the tanks were still safe and whole on the night before the battle, when a storm of wind and rain flooded the roads and turned the low ground beyond the village, which was treacherous at the best of times, into a slimy quagmire.

Before dawn on the 28th the padre walked from ruin to ruin, where the crews had taken cover from shells and the weather, and administered the Sacrament to all who desired to partake of it. The crews stood to their tanks. Then, just before sunrise, came the whine of the first shells, and our barrage fell on the shell-holes in which the enemy, crouched and sodden, lay waiting for our attack. The German gunners were alert, and in less than two minutes the counter-barrage fell beyond the village to prevent reinforcements from coming forward. Big shells crashed into St Julien. The tanks swung out of their lairs in the dust and smoke, and, moving clear of the village, advanced steadily in the dim light along the desolate road, while the padre and Wyatt slipped back through the counter-barrage to brigade headquarters.

It was lonely on the Poelcapelle Road, with nothing for company but shells bursting near the tanks. After the heavy rain the tanks slipped about on the broken setts, and every shell-hole in the road was a danger—one lurch, and the tank would slide off into the marsh.

Very slowly the tanks picked their way. Three tanks reached the cross-roads. The fourth, Lloyd's, scraped a tree-trunk, and the mischief was done. The tank sidled gently off the road and stuck, a target for the machine-gunners. Two of the crew crept out, and the unditching beam was fixed on to the tracks. The tank heaved, moved a few inches, and sank more deeply. Another effort was made, but the tank was irretrievably ditched, half a mile from the German lines.

Three tanks turned to the right at the first cross-roads, and, passing through our infantry, enfiladed the shell-holes occupied by the enemy. The effect of the tanks' fire could not be more than local, since on either side of the road were banks about four to five feet in height. The enemy were soon compelled to run back from the shell-holes near the road, and many dropped into the mud; but machine-gun fire from the shell-holes, which the guns of the tanks could not reach effectively, prevented a further advance.

One tank moved south down the track towards the strong points, but found it blocked by a derelict tank which the enemy had blown neatly into two halves. My tank remained there for an hour, shooting at every German who appeared. Then the tank commander tried to reverse in order to take another road, but the tank, in reversing, slid on to a log and slipped into a shell-hole, unable to move. One man was mortally wounded by a splinter.

The barrage had passed on and the infantry were left floundering in the mud. The enemy seized the moment to make a counter-attack, two bunches of Germans working their way forward from shell-hole to shell-hole on either side of the tank. Our infantry, already weakened, began to withdraw to their old positions.

The tank commander learned by a runner, who on his adventurous little journey shot two Germans with his revolver, that the second tank was also ditched a few hundred yards away on another road. This tank, too, had cleared the shell-holes round it, and, bolting the garrison of a small strong point near it with its 6-pdr. gun, caught them as they fled with machine-gun fire.

There was nothing more to be done. The tanks were in full view of the German observers, and the enemy gunners were now trying for direct hits. The tanks must be hit, sooner or later. The infantry were withdrawing. The two wretched subalterns in that ghastly waste of shell-holes determined to get their men away before their tanks were hit or completely surrounded. They destroyed what was of value in their tanks, and carrying their Lewis guns and some ammunition, they dragged themselves wearily back to the main road.

The remaining tank, unable to move forward as all the roads were now blocked, cruised round the triangle of roads to the north of the strong points. Then a large shell burst just in front of the tank and temporarily blinded the driver. The tank slipped off the road into the mud, jamming the track against the trunk of a tree. All the efforts of the crew to get her out were in vain....

Meanwhile, we had been sitting drearily near Divisional Headquarters on the canal bank, in the hope that by a miracle our tanks might succeed and return. The morning wore on, and there was little news. The Germans shelled us viciously. It was not until my tank commanders returned to report that we knew the attack had failed.

When the line had advanced a little, Cooper and I went forward to reconnoitre the road to Poelcapelle and to see our derelicts. Two of the tanks had been hit. A third was sinking into the mud. In the last was a heap of evil-smelling corpses. Either men who had been gassed had crawled into the tank to die, or more likely, men who had taken shelter had been gassed where they sat. The shell-holes near by contained half-decomposed bodies that had slipped into the stagnant water. The air was full of putrescence and the strong odour of foul mud. There was no one in sight except the dead. A shell came screaming over and plumped dully into the mud without exploding. Here and there was a little rusty wire, climbing in and out of the shell-holes like noisome weeds. A few yards away a block of mud-coloured concrete grew naturally out of the mud. An old entrenching tool, a decayed German pack, a battered tin of bully, and a broken rifle lay at our feet. We crept away hastily. The dead never stirred.

CHAPTER IX.

THE THIRD BATTLE OF YPRES—THE POELCAPELLE ROAD.

(September and October 1917.)

For three weeks there was no big offensive, though the artilleries continued their pitiless duel without a break, and the miserable infantry, tormented by bombs and shells as they crouched in their water-logged holes, or staggering dully over the mud in a series of little local attacks, which too often failed, could scarcely have realised that there was a distinct lull in the battle. We were pulling ourselves together for another enormous effort. The guns were pushed forward, and more guns arrived. Tired Divisions were taken out and new Divisions took their place with reduced fronts. There were new groupings, new tactics.... A possible month of fighting weather remained. We might still make something of this tragic struggle.

My company had returned from the Canal, as it was not likely that we should be wanted again in the near future, and were living in shameless comfort at La Lovie. The rain had stopped—we always had bright sunshine in the Salient, when we were not ready to attack. If it had not been for the growl of the guns, an occasional shell in Poperinghe while we were bargaining for greengages, or the perseverance of the enemy airmen, who dropped bombs somewhere in the neighbourhood each fine night, we might have forgotten the war completely. There were walks through the pine-woods, canters over the heath, thrilling football matches against our rivals, little expeditions to Bailleul for fish, or Cassel for a pleasant dinner in the cool of the evening. And I fell in with Susie.

She was a dear, graceful little woman, with timid, liquid brown eyes, black hair, a pleasant mouth, and the most marvellous teeth. Our friendship began one night when, returning from mess, I found her sitting on my bed.

It is better to be frank. She was half a German—at least we all thought so, because, if she had no dachshund blood in her, she had no other strain in her that we could recognise.

Then there was the Brigade barber across the way, who came from Bond Street. He had been given his own little shop, and he possessed such a store of the barber's polite conversation that to listen was to become home-sick. Sometimes, as we were in Flanders, he would flavour his stories a little fully, ending always with a half-apology—

"A topic, sir, I can assure you, that I should scarcely have approached, if it had not been for my eighteen months in the ranks."

His little deprecating cough was pure joy....

On the 19th the weather broke again, and it rained heavily. On the 20th we delivered an attack in the grand style, with every man and gun available. For a few days we were full of hope. The enemy could not resist our sheer strength, and their line bent and almost broke. We threw in Division after Division, attacking day after day. We thrust him back to the fringes of the Houthulst Forest. We crawled along the Passchendaele Ridge, and on the 26th we captured Zonnebeke. Then slowly and magnificently the Germans steadied themselves, and once more the attacks died down with the enemy line still in being. But the Great General Staff must have had a terrible fright.

Ward's company had been engaged between the Poelcapelle Road and Langemarck. Much to my disgust I had been compelled to hand over to him two of my best tanks. His company did excellent work, though, as had become customary in the Salient, only a few of his tanks returned. One tank particularly distinguished itself by climbing a barricade of logs, which had been built to block the road a few hundred yards south of Poelcapelle, and slaughtering its defenders.

At the end of September we had driven back the enemy, on the front with which I was principally concerned, to a position immediately in front of Poelcapelle—that is, just over a mile N.E. of the cross-roads near which Wyatt's section had fought at the end of August. Our progress in a month, though we thought it to be satisfactory at the time, had not been astonishingly rapid. It was determined to clear Poelcapelle as soon as possible, since, while the Germans held it, we were greatly handicapped in attacking either the S.E. edge of the Houthulst Forest or the Passchendaele Ridge itself from the north-west. Further, the only two main roads in the neighbourhood passed through the village.

Marris, who had succeeded Haskett-Smith in the command of No. 10 Company, was instructed to assist the infantry in the attack. His company had just returned from Wailly, where they had greatly improved their driving by hard practice over the derelict trenches. They had suffered few casualties at Arras, and, as they had not previously been engaged in the Salient, they were fresh and keen.

The attack was scheduled for October 4th. Marris brought down his tanks into St Julien and camouflaged them in the ruins. St Julien, though still easily within close field-gun range, was now respectably "behind the line." It was only shelled once or twice a night, and during the day on state occasions. It could not hope entirely to escape—the bridge across the Hannebeek was too important—but it became the place at which you left the car if you wanted to reconnoitre forward.

The attack was incredibly successful. Of Marris's twelve tanks, eleven left St Julien and crawled perilously all night along the destroyed road. At dawn they entered the village with the infantry and cleared it after difficult fighting. One section even found their way along the remains of a track so obliterated by shell-fire that it scarcely could be traced on the aeroplane photographs, and "bolted" the enemy from a number of strong points. Then, having placed the infantry in possession of their objectives, the tanks lurched back in the daylight. It was a magnificent exhibition of good driving, which has never been surpassed, and was without doubt the most successful operation in the Salient carried out by tanks.

Unfortunately the tanks could not remain in the village. By midday every German gun which could bear had been turned upon it, and by dusk the enemy had forced their way back into the ruins at the farther end of the long street.

It soon became clear that we should be required to finish the job. The weather, of course, changed. A few days of drying sun and wind were followed by gales and heavy rain. The temperature dropped. At night it was bitterly cold.

On the 6th, Cooper and I made a little expedition up the Poelcapelle Road. It was in a desperate condition, and we felt a most profound respect for the drivers of No. 10 Company. The enemy gunners had shelled it with accuracy. There were great holes that compelled us to take to the mud at the side. In places the surface had been blown away, so that the road could not be distinguished from the treacherous riddled waste through which it ran. To leave the road was obviously certain disaster for a tank. Other companies had used it, and at intervals derelict tanks which had slipped off the road or received direct hits were sinking rapidly in the mud. I could not help remembering that the enemy must be well aware of the route which so many tanks had followed into battle.

We were examining a particularly large shell-hole, between two derelict tanks, when the enemy, whose shells had been falling at a reasonable distance, began to shell the road....

Two sections of my tanks—Talbot's and Skinner's—had moved forward once more from the Canal, and were safely camouflaged in St Julien by dawn on the 8th. All the tank commanders and their first drivers had reconnoitred the road from St Julien to the outskirts of Poelcapelle. The attack was to be made at 5.20 A.M. on the 9th. The tanks were ordered to enter Poelcapelle with the infantry and drive the enemy out of the houses which they still held.

I was kept at La Lovie until dusk for my final instructions. I started in my car, intending to drive to Wieltje, two miles from St Julien, but Organ was away, and I found to my disgust that my temporary driver could not see in the dark. Naturally, no lights were allowed on the roads, and the night was black with a fluster of rain. After two minor collisions on the farther side of Vlamertinghe I gave up the car as useless, and tramped the two and a half miles into Ypres. The rain held off for an hour, and a slip of moon came out to help me.

I walked through the pale ruins, and, though the enemy had ceased to shell Ypres regularly, fear clung to the place. For once there was little traffic, and in the side streets I was desperately alone. The sight of a military policeman comforted me, and, leaving the poor broken houses behind, I struck out along the St Jean road, which the enemy were shelling, to remind me, perhaps, that there could still be safety in Ypres.

It began to rain steadily and the moon disappeared. I jumped into an empty ambulance to escape from the rain and the shells, but beyond St Jean there was a bad block in the traffic; so, leaving the ambulance, I wormed my way through the transport, and, passing the big guns on the near side of the crest which the enemy had held for so many years, I splashed down the track into St Julien. I only stumbled into one shell-hole, but I fell over a dead mule in trying to avoid its brother. It was a pitch-black night.

We had decided to use for our headquarters a perfectly safe "pill-box," or concreted house in St Julien, but when we arrived we discovered that it was already occupied by a dressing station. We could not stand upon ceremony—we shared it between us.

Soon after I had reached St Julien, weary, muddy, and wet, the enemy began to shell the village persistently. One shell burst just outside our door. It killed two men and blew two into our chamber, where, before they had realised they were hit, they were bandaged and neatly labelled.

My crews, who had been resting in our camp by the Canal, arrived in the middle of the shelling, and, paying no attention to it whatever, began to uncover their tanks and drive them out from the ruins where they had been hidden. Luckily nobody was hurt, but the shelling continued until midnight.

By 10 P.M. the tanks had started on the night's trek, with the exception of one which had been driven so adroitly into a ruin that for several hours we could not extract it. By midnight the rain had stopped and the moon showed herself—but with discretion.

Very slowly the seven tanks picked their way to Poelcapelle. The strain was appalling. A mistake by the leading tanks, and the road might be blocked. A slip—and the tank would lurch off into the mud. The road after the rain would have been difficult enough in safety by daylight. Now it was a dark night, and, just to remind the tanks of the coming battle, the enemy threw over a shell or two.

One tank tried to cross a tree-trunk at the wrong angle. The trunk slipped between the tracks and the tank turned suddenly. The mischief was done. For half an hour S. did his best, but on the narrow slippery road he could not swing his tank sufficiently to climb the trunk correctly. In utter despair he at last drove his tank into the mud, so that the three tanks behind him might pass.16

About 4 A.M. the enemy shelling increased in violence and became a very fair bombardment. The German gunners were taking no risks. If dawn were to bring with it an attack, they would see to it that the attack never developed. By 4.30 A.M. the enemy had put down a barrage on every possible approach to the forward area. And the Poelcapelle Road, along which tanks had so often endeavoured to advance, was very heavily shelled. It was anxious work, out in the darkness among the shells, on the destroyed road....

In the concrete ruins we snatched a little feverish sleep in a sickly atmosphere of iodine and hot tea. A few wounded men, covered with thick mud, came in, but none were kept, in order that the station might be free for the rush on the morning of the battle.

By four the gunnery had become too insistent. I did not expect Talbot to send back a runner until just before "zero," but the activity of the guns worried me. The Poelcapelle Road was no place for a tank on such a night. Still, no news was good news, for a message would have come to me if the tanks had been caught.

We went outside and stood in the rain, looking towards the line. It was still very dark, but, though the moon had left us in horror, there was a promise of dawn in the air.

The bombardment died down a little, as if the guns were taking breath, though far away to the right a barrage was throbbing. The guns barked singly. We felt a weary tension; we knew that in a few moments something enormously important would happen, but it had happened so many times before. There was a deep shuddering boom in the distance, and a shell groaned and whined overhead. That may have been a signal. There were two or three quick flashes and reports from howitzers quite near, which had not yet fired. Then suddenly on every side of us and above us a tremendous uproar arose; the ground shook beneath us; for a moment we felt battered and dizzy; the horizon was lit up with a sheet of flashes; gold and red rockets raced madly into the sky, and in the curious light of the distant bursting shells the ruins in front of us appeared and disappeared with a touch of melodrama....

We went in for a little breakfast before the wounded arrived....

Out on the Poelcapelle Road, in the darkness and the rain, seven tanks were crawling very slowly. In front of each tank the officer was plunging through the shell-holes and the mud, trying hard not to think of the shells. The first driver, cursing the darkness, peered ahead or put his ear to the slit, so that he could hear the instructions of his commander above the roar of the engine. The corporal "on the brakes" sat stiffly beside the driver. One man crouched in each sponson, grasping the lever of his secondary gear, and listening for the signals of the driver, tapped on the engine-cover. The gunners sprawled listlessly, with too much time for thought, but hearing none of the shells.