полная версия

полная версияA Company of Tanks

The bombardment died down a little, as if the guns were taking breath, though far away to the right a barrage was throbbing. The guns barked singly. We felt a weary tension; we knew that in a few moments something enormously important would happen, but it had happened so many times before. There was a deep shuddering boom in the distance, and a shell groaned and whined overhead. That may have been a signal. There were two or three quick flashes and reports from howitzers quite near, which had not yet fired. Then suddenly on every side of us and above us a tremendous uproar arose; the ground shook beneath us; for a moment we felt battered and dizzy; the horizon was lit up with a sheet of flashes; gold and red rockets raced madly into the sky, and in the curious light of the distant bursting shells the ruins in front of us appeared and disappeared with a touch of melodrama....

We went in for a little breakfast before the wounded arrived....

Out on the Poelcapelle Road, in the darkness and the rain, seven tanks were crawling very slowly. In front of each tank the officer was plunging through the shell-holes and the mud, trying hard not to think of the shells. The first driver, cursing the darkness, peered ahead or put his ear to the slit, so that he could hear the instructions of his commander above the roar of the engine. The corporal "on the brakes" sat stiffly beside the driver. One man crouched in each sponson, grasping the lever of his secondary gear, and listening for the signals of the driver, tapped on the engine-cover. The gunners sprawled listlessly, with too much time for thought, but hearing none of the shells.

S. was savagely attempting to unditch the tank which he had purposely driven into the mud.

The shells came more rapidly—in salvos, right on the road, on either side of the tanks. The German gunners had decided that no tank should reach Poelcapelle that night. The tanks slithered on doggedly—they are none too easy to hit....

Suddenly a shell crashed into the third tank, just as it was passing a derelict. The two tanks in front went on. Behind, four tanks were stopped. The next tank was hit on the track.

It was a massacre. The tanks could not turn, even if they had wished. There was nothing for it but to go on and attempt to pass in a rain of shells the tanks which could not move, but each tank in turn slipped off into the mud. Their crews, braving the shells, attached the unditching beams—fumbling in the dark with slippery spanners, while red-hot bits flew past, and they were deafened by the crashes—but nothing could be done. The officers withdrew their men from the fatal road and took cover in shell-holes. It was a stormy cheerless dawn.

The first two tanks, escaping the barrage, lurched on towards Poelcapelle. The first, delayed by an immense crater which the enemy had blown in the road, was hit and caught fire. The crew tumbled out, all of them wounded, and Skinner brought them back across country. The second, seeing that the road in front was hopelessly blocked—for the leading tank was in the centre of the fairway—turned with great skill and attempted vainly to come back. By marvellous driving she passed the first derelict, but in trying to pass the second she slipped hopelessly into the mud....

The weary night had passed with its fears, and standing in front of the ruin we looked down the road. It was bitterly cold, and tragedy hung over the stricken grey country like a mist. First a bunch of wounded came, and then in the distance we saw a tank officer with his orderly. His head was bandaged and he walked in little jerks, as if he were a puppet on a string. When he came near he ran a few steps and waved his arms. It was X., who had never been in action before.

We took him inside, made him sit down, and gave him a drink of tea. He was badly shaken, almost hysterical, but pulling himself together and speaking with a laboured clearness, he told us what had happened. His eyes were full of horror at the scene on the road. He kept apologising—his inexperience might lead him to exaggerate—perhaps he ought not to have come back, but they sent him back because he was wounded; of course, if he had been used to such things he would not have minded so much—he was sorry he could not make a better report. We heard him out and tried to cheer him by saying that, of course, these things must happen in war. Then, after he had rested a little, we sent him on, for the dressing station was filling fast, and he stumbled away painfully. I have not seen him since.

The crews had remained staunchly with their tanks, waiting for orders. I sent a runner to recall them, and in an hour or so they dribbled in, though one man was killed by a chance shell on the way. Talbot, the old dragoon, who had fought right through the war, never came back. He was mortally wounded by a shell which hit his tank. I never had a better section-commander.

We waited until late in the morning for news of Skinner, who had returned across country. The dressing station was crowded, and a batch of prisoners, cowed and grateful for their lives, were carrying loaded stretchers along trench-board tracks to a light railway a mile distant. Limbers passed through and trotted toward the line. Fresh infantry, clean and obviously straight from rest, halted in the village. The officers asked quietly for news. At last Cooper and I turned away and tramped the weary muddy miles to the Canal. The car was waiting for us, and soon we were back at La Lovie. I reported to the Colonel and to the Brigade Commander. Then I went to my hut, and, sitting on my bed, tried not to think of my tanks. Hyde, the mess-waiter, knocked at the door—

"Lunch is ready, sir, and Mr King has got some whisky from the canteen, sir!"

I shouted for hot water....

The great opportunity had gone by. We had failed, and to me the sense of failure was inconceivably bitter. We began to feel that we were dogged by ill-fortune: the contrast between the magnificent achievement of Marris's company and the sudden overwhelming disaster that had swept down on my section was too glaring. And we mourned Talbot....

During the next few days we made several attempts to salve our tanks or clear the road by pulling them off into the mud, but the shells and circumstances proved too much for individual enterprise. In the following week, after the enemy at last had been driven beyond Poelcapelle, I sent Wyatt's section forward to St Julien, and, working under the orders of the Brigade Engineer, they managed to clear the road for the passage of transport, or, with luck and good driving, of tanks.

Later, there was a grandiose scheme for attacking Passchendaele itself and Westroosebeke from the north-west through Poelcapelle. The whole Brigade, it was planned, would advance along the Poelcapelle and Langemarck Roads and deploy in the comparatively unshelled and theoretically passable country beyond. To us, perhaps prejudiced by disaster, the scheme appeared fantastic enough: the two roads could so easily be blocked by an accident or the enemy gunners; but we never were able to know whether our fears were justified, for the remains of the Tank Corps were hurriedly collected and despatched to Wailly....

The great battle of the year dragged on a little longer. In a few weeks the newspapers, intent on other things, informed their readers that Passchendaele had fallen. The event roused little comment or interest. Now, if we had reached Ostend in September … but it remains to be seen whether or not tanks can scale a sea-wall.

CHAPTER X.

THE BATTLE OF CAMBRAI—FLESQUIERES.

(November 4th to 20th, 1917.)

From La Lovie in the Salient I went on leave. I was recalled by wire on the 4th November to discover that, during my absence, the battalion had moved south to our old training-ground at Wailly. The apathy and bitter disappointment, caused by our misfortunes on the Poelcapelle Road, had disappeared completely, and the company, scenting a big mysterious battle, was as eager and energetic as if it had just disembarked in France.

For once the secret was well kept. The air was full of rumours, but my officers knew nothing. It was not until I saw the Colonel that I learnt of the proposed raid on Cambrai, and discovered to my great joy that we were to attack in company with the Fifty-first Division.

This Division of Highland Territorials had won for itself in the course of a year the most astounding reputation. Before Beaumont Hamel in November '16 it had been known as "Harper's Duds." Since that action it had carried out attack after attack with miraculous success, until at this time it was renowned throughout the British Armies in France as a grim and terrible Division, which never failed. The Germans feared it as they feared no other.

We trained with this splendid Division for ten days, working out the plans of our attack so closely that each platoon of Highlanders knew personally the crew of the tank which would lead it across No Man's Land. Tank officers and infantry officers attended each other's lectures and dined with each other. Our camp rang at night with strange Highland cries. As far as was humanly possible within the limits of time, we discussed and solved each other's difficulties, until it appeared that at least on one occasion a tank and infantry attack would in reality be "a combined operation."

The maps and plans which we used in these pleasant rehearsals were without names, but although this mystery added a fillip of romance to our strenuous preparations, we were met by a curious difficulty—we did not dare to describe too vividly the scene of the coming battle for fear the area should be recognised. There was a necessary vagueness in our exhortations....

One fine day Cooper, Jumbo, and I motored over to this nameless country. We passed through the ruins of Bapaume and came to the pleasant village of Metz-en-Couture on the edge of the great Havrincourt Wood. Leaving our car, we walked over the clean grassy hills to the brand-new trench system, then lightly held by the Ulster Division.

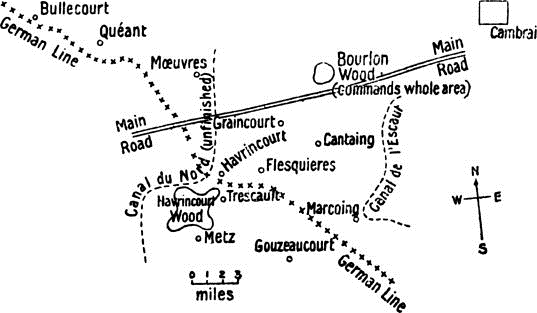

It was a country of bare downs, occasional woods, sunken roads, plentiful villages, surprising chalk ravines, and odd disconnected mounds, and the key to it was Bourlon Wood.

You will remember that on the east of the Bullecourt front was the Quéant Salient. Beyond it the German defences then ran suddenly to the south in order to obtain the protection of the enormous, unfinished Canal du Nord. By Havrincourt village, which was set conspicuously on the side of a hill, the Canal met Havrincourt Wood, and the enemy line turned again to the east, skirting the fringes of the wood and continuing cleverly at the foot of a range of low chalk hills. A rough diagram may make this clear, and will enable you to connect this battle with the lesser battles of Bullecourt.

The front which concerned my brigade extended from Havrincourt to east of Flesquieres. Havrincourt itself was defended on the west by the Canal, and on the south by a ravine and the outlying portions of the great wood. In front of the German trenches the trees had been cut down, so that the approach was difficult and open. East of Havrincourt the German trenches were completely hidden from view by the lie of the ground. This method of siting trenches was much favoured by the Germans at the time. Clearly it prevented direct observation of fire. Further, it compelled tanks to start on their journey across No Man's Land, unable to see the trenches which they were about to attack.

The trenches on the slope immediately behind the enemy first line were in full view, and the roads, buildings, patches of chalk, distinctively-shaped copses, would provide useful landmarks, if they were not hidden by the smoke of battle.

Apart from its natural defences the Hindenburg System was enormously strong. In front of it there were acres of low wire. The trenches were wide enough to be serious obstacles to tanks. Machine-gun posts, huge dug-outs, long galleries, deep communication trenches, gun-pits—the whole formed one gigantic fortification more than five miles in depth.

Yet we came back from our reconnaissance in the firm belief that tanks could break through this fortification without any difficulty at all. The ground was hard chalk, and no amount of rain could make it unfit for our use. Natural and artificial obstacles could be surmounted easily enough or avoided. Given sufficient tanks and the advantage of surprise, there was no earthly reason why we should not go straight through to Cambrai. What could stop us? The wire? It did not affect us in the slightest. The trenches? They were a little wide, but we knew how to cross them. Guns? There were not many, and few would survive the duel with our own artillery. Machine-guns or armour-piercing bullets? The Mk. IV. tank was practically invulnerable. If the infantry were able to follow the tanks, the tanks would see them through the trench systems. In open country it would be for common-sense and the cavalry, until the enemy filled the gap with his reserves.

We were only troubled by the thought of Bourlon Wood, which, from its hill, dominated the whole countryside between Havrincourt and Cambrai. But Bourlon Wood was only a matter of 7000 yards behind the German lines. If we were to break through at all, we should take the wood in our stride on the first day.

Jumbo expressed our feelings admirably—

"Unless the Boche catches on before the show, it's a gift!"

We returned to Wailly bubbling over with enthusiasm. The last rehearsals were completed, and our future comrades, the 6th Black Watch and the 8th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, appeared implicitly to trust us. We tuned our engines and practised with the wily "fascine."

Fascine is the military term for "faggot." Each of our fascines was a huge bundle of brushwood, weighing over one ton. By an ingenious mechanism it could be hoisted on to the roof of the tank. When a dangerously wide trench was reached, the driver pulled a rope, the fascine gently rolled off the tank into the trench, and the tank crossed at its ease. It was a simple device that produced an astonishing amount of bad language. Entraining was hideously complicated. Dropping the fascine on to the truck in front of the tank requires care and precision, while obviously if a fascine refuses to be picked up again, tanks are prevented from coming off the train....

At dawn on the 13th we arose and trekked a matter of five miles to Beaumetz Station, where, after an excellent and hilarious lunch at the local estaminet, we entrained successfully for an unknown destination, although it took a little time to arrange the fascines on the trucks so that they would not fall off in the tunnels.

I watched the trains pull out from the ramps. The lorries had already started for our next halting-place. We were clear of Wailly. I motored down to the neighbourhood of Albert, and at dusk my car was feeling its way through a bank of fog along the road from Bray to the great railhead at Le Plateau, at the edge of the old Somme battlefield.

It was a vast confusing place, and even a major in the Tank Corps felt insignificant among the multitudinous rails, the slow dark trains, the sudden lights. Tanks, which had just detrained, came rumbling round the corners of odd huts. Lorries bumped through the mist with food and kit. Quiet railwaymen, mostly American, went steadily about their business.

I found a hut with a fire in it and an American, who gave me hot coffee and some wonderful sandwiches, made of sausage and lettuce, and there I sat, until, just after midnight, word came that our train was expected. We walked to the ramp, and at last after an interminable wait our train glided in out of the darkness. There was a slight miscalculation, and the train hit the ramp with a bump, carrying away the lower timbers, so that it could not bear the weight of tanks.

Wearily we tramped a mile or so to another ramp. This time the train behaved with more discretion. The tanks were driven off into a wood, where they were carefully camouflaged; the cooks set to work and produced steaming tea; officers and men made themselves comfortable. Then we set off in our car again. The mist still hung heavily over the Somme battlefield and we continually lost our way. It was dawn before a desperately tired company headquarters fell asleep in some large and chilly huts near Meaulte.

That day (the 14th) and the next the men worked at their tanks, adjusting the fascines and loading up with ammunition, water, and rations. On the 14th we made another careful survey of our trenches and, through our glasses, of the country behind the German line. On the night of the 15th I walked along the tank route from our next detraining station at Ytres to our final lying-up position in Havrincourt Wood, a matter of seven miles, until I personally knew every inch of the way beyond any shadow of doubt.

At dusk on the 16th I was waiting on the ramp at Ytres for my tanks to arrive, when I heard that there had been an accident to a tank train at a level-crossing a mile down the line. I hurried there. The train had collided with a lorry and pushed it a few hundred yards, when the last truck had been derailed and the tank on it had crushed the lorry against the slight embankment. Under the tank were two men. I was convinced that I had lost two of my men, until I discovered that the tanks belonged to Marris and the two unfortunate men had been on the lorry. The line was soon cleared. The derailed truck was uncoupled, and the tank, none the worse for its adventure, climbed up the embankment and joined its fellows at the ramp.

My tanks detrained at midnight without incident, and we were clear of the railhead in an hour. It was a strange fatiguing tramp in the utter blackness of the night to Havrincourt Wood—past a brickyard, which later we were to know too well, through the reverberating streets of Neuville Bourjonval, where three tanks temporarily lost touch with the column, and over the chill lonely downs to the outskirts of Metz, where no lights were allowed. We felt our way along a track past gun-pits and lorries and waggons until we came to the outskirts of the great wood. There we fell in with Marris's tanks, which had come by another route. At last we arrived at our allotted quarter of the wood, three thousand yards from the nearest German. The tanks pushed boldly among the trees, and for the next two hours there was an ordered pandemonium. Each tank had to move an inch at a time for fear it should bring down a valuable tree or run over its commander, who probably had fallen backwards into the undergrowth. One tank would meet another in the darkness, and in swinging to avoid the other, would probably collide with a third. But by dawn—I do not know how it was done—every tank was safely in the wood; the men had fallen asleep anywhere, and the cooks with sly weary jests were trying to make a fire which would not smoke. Three thousand yards is a trifle near....

For the next five days we had only one thought—would the Boche "catch on"? The Ulster Division was still in the line, and, even if the enemy raided and took prisoners, the Ulstermen knew almost nothing. By day the occasional German aeroplane could see little, for there was little to see. Tanks, infantry, and guns were hidden in the woods. New gun-pits were camouflaged. There was no movement on the roads or in the villages. Our guns fired a few customary rounds every day and night, and the enemy replied. There was nothing unusual.

But at night the roads were blocked with transport. Guns and more guns arrived, from field-guns to enormous howitzers, that had rumbled down all the way from the Salient. Streams of lorries were bringing up ammunition, petrol, rations; and whole brigades of infantry, marching across the open country, had disappeared by dawn into the woods. Would the Boche "catch on"?…

There was but little reconnaissance for my men to carry out, since the route to No Man's Land from the wood was short and simple. And to see the country behind the enemy trenches it was necessary only to walk a mile to the reserve trench beyond the crest of the hill, where an excellent view could be obtained from an observation post.

By this time we knew the plan of the battle. At "zero" on the given day we would attack on a front of approximately ten thousand yards, with the object of breaking through the Hindenburg System into the open country. It was essential to seize on the first day the bridges over the Canal de l'Escaut and Bourlon Wood. We gathered that, if we were successful, we should endeavour to capture Cambrai and to widen the gap by rolling up the German line to the west.

On the front of our battalion, immediately to the east of Havrincourt itself and opposite Flesquieres, Marris's company and mine were detailed to assist the infantry in capturing the first system of trenches. Ward's company was reserved for the second system and for Flesquieres itself. The surviving tanks of all three companies would collect in Flesquieres for a possible farther advance to the neighbourhood of Cantaing.

On the left was "G" Battalion, with Havrincourt village as its first main objective, and on our right was "E" Battalion, beyond which were the 2nd and 3rd Brigades of the Tank Corps. There was one tank to every thirty yards of front!

Until the 17th the enemy apparently suspected nothing at all; but on the night of the 17th–18th he raided and captured some prisoners, who fortunately knew little. He gathered from them that we were ourselves preparing a substantial raid, and he brought into the line additional companies of machine-gunners and a few extra field-guns.

The 19th came with its almost unbearable suspense. We did not know what the Germans had discovered from their prisoners. We could not believe that the attack could be really a surprise. Perhaps the enemy, unknown to us, had concentrated sufficient guns to blow us to pieces. We looked up for the German aeroplanes, which surely would fly low over the wood and discover its contents. Incredibly, nothing happened. The morning passed and the afternoon—a day was never so long—and at last it was dusk.

At 8.45 P.M. my tanks began to move cautiously out of the wood and formed into column. At 9.30 P.M., with engines barely turning over, they glided imperceptibly and almost without noise towards the trenches. Standing in front of my own tanks, I could not hear them at two hundred yards.

By midnight we had reached our rendezvous behind the reserve trenches and below the crest of the slope. There we waited for an hour. The Colonel arrived, and took me with him to pay a final visit to the headquarters of the battalions with which we were operating. The trenches were packed with Highlanders, and it was with difficulty that we made our way through them.

Cooper led the tanks for the last half of the journey. They stopped at the support trenches, for they were early, and the men were given hot breakfast. The enemy began some shelling on the left, but no damage was done.

At 6.10 A.M. the tanks were in their allotted positions, clearly marked out by tapes which Jumbo had laid earlier in the night....

I was standing on the parados of a trench. The movement at my feet had ceased. The Highlanders were ready with fixed bayonets. Not a gun was firing, but there was a curious murmur in the air. To right of me and to left of me in the dim light were tanks—tanks lined up in front of the wire, tanks swinging into position, and one or two belated tanks climbing over the trenches.

I hurried back to the Colonel of the 6th Black Watch, and I was with him in his dug-out at 6.20 A.M. when the guns began. I climbed on to the parapet and looked.

In front of the wire tanks in a ragged line were surging forward inexorably over the short down grass. Above and around them hung the blue-grey smoke of their exhausts. Each tank was followed by a bunch of Highlanders, some running forward from cover to cover, but most of them tramping steadily behind their tanks. They disappeared into the valley. To the right the tanks were moving over the crest of the shoulder of the hill. To the left there were no tanks in sight. They were already in among the enemy.

Beyond the enemy trenches the slopes, from which the German gunners might have observed the advancing tanks, were already enveloped in thick white smoke. The smoke-shells burst with a sheet of vivid red flame, pouring out blinding, suffocating clouds. It was as if flaring bonfires were burning behind a bank of white fog. Over all, innumerable aeroplanes were flying steadily to and fro.