полная версия

полная версияSpain

These events, however, had shown the necessity of tightening the reins of discipline in the army. Salmeron, who was now at the head of the ministry, exerted himself to restore order, and endeavoured to work the republic in a conservative sense. A year or two after, at the instigation of Castelar, the penalty of death for mutiny was again enforced. After Moriones and Serrano in the north had both failed in their attempts to raise the seige of Bilbao, Concha at last succeeded, May 2, 1874; and Martinez Campos, who had crushed the insurrection in Valencia, was making way against the Carlists in Aragon and Catalonia. Between these generals, with Pavia and others, a conspiracy was formed to restore the Bourbon monarchy under Alfonso XII., son of Isabella. Serrano offered only a doubtful resistance, and Castelar, opposed by the intransigente party, found himself almost alone in upholding a conservative republic. The death of Concha, before Estella, in Navarre, June 27, 1874, delayed for some months the proclamation of Alphonso, but at length it took place, on December 30, 1874, and the republic fell without a struggle. Alphonso XII. landed at Barcelona in the first days of 1875, and entered Madrid on January 14th. In spite of some checks, caused by the incapacity of his generals, his power was quickly augmented. Many who, through hatred of the republic and of the cantonalist excesses, had joined the Carlist ranks, abandoned the cause when monarchy was restored. Don Carlos had proved to be as incapable as his grandfather had been, and much less reputable in his private life. By the end of August, Martinez Campos had taken Urgel, in Catalonia, and by the close of the year he was free to assist Quesada in the Basque Provinces. The united armies were successful, and on February 28, 1876, Don Carlos entered France, leaving his followers and the Basque Provinces entirely at the mercy of the conquerors. The consequence to them has been the partial loss of their fueros, the incorporation of the Basque conscripts with the rest of the army, and the annexation of the provinces for the first time to the crown of Spain.

With Alphonso XII. entered Spain, as his chief adviser, Cánovas del Castillo. Whether nominally prime minister, or out of office, he has really held the reins of power—with the exception of the nine months' ministry of Martinez Campos in 1879—from 1875 to February, 1881. On the whole his exertions have been beneficial to Spain. By an arrangement dated January 1, 1877, and by lowering the rate of interest, he saved the public credit, which was on the verge of utter bankruptcy. Insensibly he has detached himself from the progressive liberal movement, and his rule has become more and more conservative. The decree for toleration of religion, passed in the first months of the republic of 1868, has been greatly modified, and interpreted in a sense more and more unfavourable to religious freedom: But he has not succeeded in breaking down the many abuses of the administration, or in putting an end to the corruption of the upper employés, or in insuring freedom and purity of parliamentary election; and until this is effected the future of Spain must still be doubtful.

Present Constitution and Administration of Spain

It would be tedious and little instructive to our readers to detail the various constitutions under which Spain has been governed since 1812. We will give a sketch, as far as we are able, of the last only. By a comparison of this with the constitution of Cadiz, it will be seen that, in spite of all reactions, Spain has really progressed in the way of freedom and good government.

The constitution of the Spanish monarchy, June 30, 1876, declares Alphonso XII. de Bourbon to be the legitimate King of Spain. His person is inviolable, but his ministers are responsible, and all his orders must be countersigned by a minister. The legislative power resides in the Cortés with the king. The Cortés is composed of two legislative bodies, equal in power—the Senate and the Congress of Deputies.

The Senate is composed (1) of senators by their own right, who are—sons of the kings, grandees of Spain with 3000l. yearly income, the Captain-General of the Forces, the Admiral-in-Chief, the Patriarch of the Indies, the Archbishops, the Presidents of the Council of State, of the Supreme Tribunal, of the National Accounts, of the Council of War, and of Marine, after two years' service; (2) of life senators, named by the crown; (3) of senators elected by the corporations of the State, or the richest citizens—half of these must be renewed every five years. All senators must be thirty-five years of age, and the number of classes (1) and (2) together must not exceed that of the elected senators, which is fixed at 180.

The Congress of Deputies is returned by the electoral Juntas, one deputy being elected for every 50,000 souls. Deputies are elected by universal suffrage, and for a period of five years. The Congress meets every year at the summons of the king, who has power to suspend or close the session; but in the latter case, a new Congress must meet within three months. The president and vice-presidents of the Senate are nominated by the king, those of the Congress are elected from its own body. The initiation of the laws belongs to the king, and to both legislative bodies; but the budget, and all financial matters, must be first presented every year to the Congress of Deputies. No one can be compelled to pay any tax not voted by Congress, or by the legally appointed corporations. The sittings are public, and the person of deputies is inviolable. Ministers may be impeached by the deputies, but are judged by the Senate.

Justice is administered in the king's name, and judges and magistrates are immovable.

The provinces are administered (1) by a governor, who, with his immediate subordinates, is nominated by the Government; (2) by a Provincial Deputation, elected by the householders of the province. All members must be natives of, or residents in, the province; their number varies according to the population. (3) Five members elected from the Provincial Deputation form a Provincial Commission to conduct business when the deputation is not sitting. These authorities and bodies answer nearly to the prefects and general councils of the French departments. They are of much greater political importance in those provinces which have preserved some of their ancient rights than in others.

Below the provincial are the municipal authorities, the Alcaldes (mayors), Ayuntamientos (municipal councils), and the Juntas Municipales. The internal administration of every parish is entrusted to an Ayuntamiento or municipal council, elected by the residents, and composed of the Alcalde or mayor, the Tenientes or assistants, the Regidores or councillors. The Junta Municipal is composed of all the councillors of the Ayuntamiento, and an assembly of three times their number, and by them the municipal accounts are to be audited and revised. The number of the Ayuntamiento varies according to the population; one Alcalde, one Teniente, six Regidores, for 1000; and one Alcalde, ten Tenientes, thirty-three Regidores, for 100,000. The real independence and free action of these bodies varies much in different provinces and in different circumstances. The smaller bodies are quite under the thumb of the central government; the larger ones in the great towns and in the more independent provinces are much less easily influenced.

The Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman is declared to be the religion of the State, and the nation is bound to maintain its worship and its ministers. "But no one shall be molested on Spanish ground for his religious opinions, nor for the exercise of his respective worship, except it be against Christian morals. Nevertheless, no other ceremonies or public manifestations shall be permitted than those of the religion of the State." These last two articles are evidently equivocal, and subject to great diversity of interpretation and of application.

All foreigners are free to settle in Spanish territory, and to exercise therein their respective trades and professions, with the exception of those which require special titles. The expression of opinion, the press, the right of public meeting, of association, and of petition, except from armed bodies, are respectively free. No Spaniard or foreigner can be arrested or detained illegally. He must either be set at liberty or be brought before a judge within twenty-four hours of his arrest. No Spaniard can be arrested without a judge's warrant, and the case must then be heard within seventy-two hours after his arrest; otherwise he must be set at liberty on his own petition or on that of any other Spaniard. Domicile is inviolable. Such are the principal articles of the present Spanish Constitution. In spite of the excess of some republican governments and the reaction of others, real progress has been made, excepting only in the equivocal law on religion, and that on marriages between Catholics and Protestants.

Administrative Spain

For military purposes, Spain is mapped out into five "capitanias generales," conferring the rank of field-marshal on the possessors of that office. The number of marshals, generals, and superior officers of the special corps in active service is over 500. The number of the army on a peace footing is fixed at 90,000, the infantry numbering 60,000, the cavalry 16,000, artillery 10,000, and engineers 4000. Universal conscription is nominally obligatory, but with the power of purchasing a substitute for a fixed sum of 80l. The time of service is eight years, four of which are spent in the active army and four in the reserve. In the colonies the time is four years only, the whole of which must be spent in active service. Besides the regular army in Spain are the corps and garrisons in the Philippine Islands, in Porto Rico, and in Cuba, where the mortality is so great that the troops need constant renewal. In addition to the above must be reckoned the militia of the Canary Islands, the "guardias civiles," a kind of constabulary like that of Ireland or the gendarmerie of France. These are about 15,000 men, and are some of the best and most trustworthy troops in Spain; the carabineros or custom-house officers, who guard the frontiers, form another corps of about 12,000. Towards the close of the late Carlist and Cuban wars the actual army was far above these numbers, and it is probable that 150,000 men were under arms on the side of the Government in the Basque Provinces alone. The Spanish soldier is one of the best in Europe, if properly commanded. He is sober, and has great powers of endurance; is an excellent marcher, and a trustworthy sentinel; persistent both in attack and defence, he still retains the steadiness of the old Spanish "tercios," which were once the terror and admiration of Europe. The Basques under Zumalacarrégui in the first Carlist war, and the Catalans under Martinez Campos in the last, earned high praise from all foreign officers who saw them. But too often these fine qualities of the private have been rendered of no avail, owing to the utter want of skill and competency in the officers and commanders, and still more by reckless corruption and mismanagement in all things relating to the commissariat and supplies. Another element of deterioration has been the use of the soldiery as mere tools of political intrigue in the frequent revolts and pronunciamientos of ambitious generals. The scientific corps, however, the artillery and engineers, have always stood aloof from sedition. It was an attempt to corrupt the former and to assimilate it in this respect to the rest of the army, which led to the abdication of King Amadeo. The generals who have achieved the greatest reputation in the Spanish army are Quesada and Martinez Campos. Moriones, who distinguished himself in the Basque Provinces during the last Carlist war, has lately died. Blanco and Jovellar acquired distinction in Cuba, and Loma as a good brigadier in the Carlist war. Serrano, Pavia, and others are better known in the field of politics than in that of military action.

For naval purposes the coast of Spain is divided into three departments—Ferrol, Cadiz, and Cartagena, at each of which ports is a naval arsenal. The jurisdiction of the marine extends as far as the tide and seventy feet beyond. The three departments, are divided into tercios navales, partidos maritimos, and districts. The Spanish navy consists of 121 ships, five of which are armoured vessels of the first class, and eleven unarmoured; eighteen belong to the second class, and fifty-six to the third, some of which are monitors and armoured gunboats. There are also thirty-one smaller vessels, and a few ships employed for training and for harbour services. The whole fleet mounts 525 guns, and is over 20,000 horse-power. The sailors number 14,000, with 504 officers of all ranks, and the marine infantry 7000, with 374 officers. The old fame of Spanish ship-building, except for small vessels, has almost entirely passed away. In the great war at the beginning of the century, the finest vessels of our navy were prizes taken from Spain. Spanish navigators, too, have long lost their old renown, though the Basques are still esteemed as mariners. The ironclad frigates and monitors of modern Spain have been almost all constructed in foreign dockyards. The armoured gunboats, however, built in Spain are a good and useful model.

The merchant marine consists of 226 ocean-going steamers and 1578 ocean sailing-vessels measuring altogether 460,000 tons. Smaller vessels make up a total of 3000 merchant-ships, less than one-fifth of the number of those of Great Britain.

For the administration of justice the country is divided into Audiencias Territoriales, Provincias, and Partidos Judiciales. The Audiencias, or courts of appeal, are fifteen, with 373 judges or procureurs. There are also 500 judges of first instance, and there is also a justice of peace or alcalde in each town or municipality. All pleadings are still conducted in writing in Spain; there is no verbal examination or cross-examination in public. Suits both civil and criminal are thus dragged out to an inordinate length. Judges are still suspected of being open to bribery, and confidence in the just administration of the law is as a consequence severely shaken. It is not uncommon for witnesses to be summoned to testify to facts which happened many years before, and it not unfrequently happens that either the principal witnesses or the criminal himself is dead before the case is decided. As a conspicuous instance, we may remind our readers that General Prim was assassinated in open day in Madrid in 1870, and the case has not yet been adjudged. The discipline of the prisons is in general extremely lax, and many crimes, especially forgeries, are there concocted with impunity. There is, however, a great difference in the treatment of the prisoners in different prisons. Up to 1840 the office of Alcaide, or governor of a prison, was sold by the Government to the highest bidder, and the purchasers made the most they could out of the wretched prisoners by starving them or by accepting bribes for illicit indulgences, and for furnishing what they were bound to provide, so that it was commonly said "that the bagnios of Algiers were less terrible than the prisons of Spain." Perhaps the worst of them all, up to the year 1833, was the old prison of the city of Madrid, one dark dungeon of which was termed "El Infierno"—Hell. Almost as bad was the Prison de Corté and the famous Saladero. There was no classification, no cleanliness, and in some of the cells neither light nor ventilation. In some of the country prisons the cells were like the dens of a menagerie, and the starving prisoners thrust their hands through the bars to beg food of passers-by. At last has arisen an ardent band of philanthropists, of whom Senors Lastres and Vilalva are at the head, and the first stone of a new prison in Madrid, arranged on modern principles, was laid by the king in February, 1877.

Hospitals, lunatic asylums, and asylums for the sick and aged poor, and other charitable establishments are of very varied descriptions in Spain. Some of them, like the famous establishments of Cadiz, Seville, Madrid, Cartagena, Valencia, and Cordova, are admirably managed, and yield in practical benefit to none of other lands. The first lunatic asylum ever founded was that at Valencia by Padre Jofre Gilanext, in 1409; three others, at Saragossa, Toledo, and Seville were founded in the fifteenth century. That of Barcelona is said to be now the best public lunatic asylum in Spain. Many others are nearly as good, while one or two of the private asylums near Madrid are excellent; but in some provinces these establishments, both public and private, are still in a very wretched state.

Since 1848 there have been a little over 4000 miles of railway laid down in Spain. The principal lines are the two which run from the extreme ends of the French Pyrenees to the capital, connecting Spain with the great European communications. Next in importance are those from the Mediterranean ports Valencia, Alicante, Cartagena, to Madrid; Malaga and Granada are connected with the metropolis by the line from Cadiz. A rather circuitous route by Badajoz, Ciudad Real, and Toledo is the only line at present open to Lisbon, but a more direct one is in course of construction. The communications with the extreme north-west are not yet completed, but the branch of the Great Northern Company from Santander, which brings the products of the Asturian coal-fields to Madrid, is of great importance. Other valuable lines are those of the valley of the Ebro, from Miranda del Ebro by Saragossa to Barcelona. Should any of the schemes projected for a direct route from Paris to Madrid, by any of the central passes of the Pyrenees, through Saragossa, be carried into effect, the line from the latter place to Madrid will be one of considerable traffic. The coast-line from Barcelona to Valencia is of great value to one of the richest wine and fruit districts of Spain. Shorter lines, which may have a considerable influence on the welfare of the country, are those which connect the great mineral fields with the chief lines of transport or with the nearest port. It has been remarked that hitherto, with some exceptions, Spanish railways have had less influence in developing local traffic than those of any other European country. The Great Northern lines, too, have suffered seriously from interruptions caused by civil war, by floods, and other accidents since 1868.

The total length of the telegraph lines is nearly 10,000 miles. The number of public offices is 324, of private, 12; the telegrams despatched amounted in 1877 to 2,023,579, of which about half were private despatches for the interior. The expenses of working were 165,076l., and the receipts 156,950l., leaving a deficit of 8126l.

The number of post-offices in 1877 was 2530, of letters 78,446,000; postal cards, 1,040,000; newspapers, 38,479,000; books and samples, 5,767,000. To Great Britain were despatched, in 1879: Letters and postal cards, 1,083,000; books, &c., 317,900; total, 1,400,900. From Great Britain: Letters and postal cards, 931,100; books, &c., 646,100; total, 1,577,200. The receipts from the post-office in 1877 were 361,704l., while the expenditure was 297,412l., leaving a surplus of 64,292l.

The Finances of Spain

The most prominent circumstance in the financial condition of Spain is the startling increase of the public debt since the revolution of 1868. The capital of the debt was then 212,443,600l., the interest of which was 5,580,000l. The funds, three per cents, were then at 33. In 1880 the capital of the debt amounted to 515,000,000l. Since 1870, by abuse of credit, the interest of the debt had been paid from the capital; then one-third of the interest was paid in paper, with a promise to pay the remaining two-thirds in coin; this engagement was soon broken, but the paper was punctually paid until 1874, when the interest of the debt was erased from the budget. In face of the evident bankruptcy of the country, an arrangement was made in 1876 between the Government and the principal foreign fund-holders, by which, from January 1, 1877, to June 30, 1881, inclusive, the interest to be paid on the three per cents was reduced to one per cent., and that on the six per cents to two per cent. From June 30, 1881, to June 30, 1882, one and a quarter per cent. will be paid, and arrangements as to future payments are to be made before the last-mentioned date, and a return to a full interest of three and six per cent. is to follow at fixed periods. The success of the scheme is shown by the fact that in 1876 the three per cents, still nominally paying three per cent. interest, were at 11½; in January, 1881, paying only one per cent. interest, they were quoted at 22; and the six per cents, paying only two per cent. interest, were at 42.

From the above statement we may gather some idea of what the civil wars of the republic, the cantonal, Carlist, and Cuban insurrections, joined to the expensive experiments of well-intentioned but inexperienced financiers, in remitting taxes while the public burdens were increasing, have cost the nation. A calm observer, Mr. Phipps, in his official report to the British Government, calculates that from 1868 to 1876 the addition to the debt from these causes amounted to at least 260,000,000l., considerably more than the total debt of Spain in 1868.

Notwithstanding the plausible balance-sheets annually submitted to Congress, the revenue and expenditure of Spain are still far from being in a satisfactory condition. The writer above quoted states that "enormous deficits in the budgets (however nominally balanced) have been the invariable rule in Spain during a long course of years, under every sort of régime and under all circumstances." In the last budget, 1879-80, the revenue is stated at 32,494,552l., and the expenditure at 33,129,484l. Supposing these figures to be correct, the deficit, 634,932l., would be far less than for many years past.

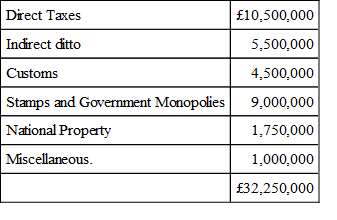

The principal sources of Spanish revenue are, in round numbers:—

Of these the items most foreign to an Englishman's notion of taxation are the produce of the seven great tobacco factories, Seville, Madrid, Santander, Gijon, Corunna, Valencia, and Alicante, of which the net revenue is over 2,500,000l., the lotteries, which bring in 5000,000l. net, the consumo tax, a kind of octroi, and the territorial tax, which together furnish the largest contribution to the revenue. The national property comprises the Almaden quicksilver-mines, valued at over 250,000l. per annum, the Linares mines, leased at 20,000l., and other sources about 30,000l. annually.

The heaviest item in the expenditure is the interest on the national debt, over 11,500,000l.; the ministry of war and the navy exceeds 6,000,000l., while pensions absorb 1,750,000l., public works over 3,000,000l., finance over 5,000,000l., administration of justice more than 2,000,000l.; the ministry of the interior, Cortés, the civil list, &c., make up the remainder.

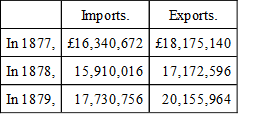

The total imports and exports of Spain were:—

But of this increased prosperity far more than her share has fallen to France, owing chiefly to its being put in the same category with Germany, Italy, Belgium, and Austria, as most favoured nations, who import their goods under the customs tariff of July 17, 1877, while England and the United States continue-under the old tariff, as favoured nations only. This disproportion will probably be still more marked, owing to the immense importation of Spanish wines into France required to make up for losses by the phylloxera disease; while the exportation of sherry to England has been gradually lessening for some years, and now we take only some 4 per cent, of the quantity, and 12 per cent in value, of the wine exported from Spain. One of our chief imports into Spain, coal, is likely also to diminish, owing to the development of the native coal-fields in the Asturias and in Andalusia. Our other chief exports from Spain in fruits and minerals largely increase. The present wine tariff of England, by which she virtually refuses to purchase the bulk of Spanish wines in their natural state, while importing them largely when mixed with inferior French white wines, and treated as clarets, &c., is felt by Spaniards to be so unfair that, until this system is modified there is little hope of obtaining a better tariff for English manufactures; while the making Gibraltar an immense depôt for a contraband trade is a wrong that rankles in the mind of all southern Spaniards. The decline of the English import trade into Spain would be much more marked but for the immense amount of English capital employed in the larger mining and industrial enterprises.