полная версия

полная версияOn the Philosophy of Discovery, Chapters Historical and Critical

283

I have also, in the same place, given the Inductive Pyramid for the science of Optics. These Pyramids are necessarily inverted in their form, in order that, in reading in the ordinary way, we may proceed to the vertex. Phil. Ind. Sc. b. xi. c. vi.

284

Cosmos, vol. ii. note 35.

285

The reader will probably recollect that as Induction means the inference of general propositions from particular cases, Deduction means the inference by the application of general propositions to particular cases, and by combining such applications; as when from the most general principles of Geometry or of Mechanics, we prove some less general theorem; for instance, the number of the possible regular solids, or the principle of vis viva.

286

B. vi. c. v.

287

c. vi.

288

Hist. b. vi. c. vi. sect. 13.

289

Hist. Ind. Sc. b. viii.

290

Reprinted in the Appendix to this volume.

291

Phil. Pos. t. iv. p. 264.

292

Logic, b. vi. c. 3.

293

Jones, On Rent, 1833.

294

Literary Remains, 1859.

295

The substance of this and the next chapter was printed as a communication to the Cambridge Phil. Soc. in 1840.

296

Or in the earlier editions, in the Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences.

297

Phil. of Biol. c. v.

298

Hist. Ind. Sc. b. ix. c. iii.

299

Ibid. b. vii. c. ii.

300

Sir W. Hamilton's Note on the Philosophy of the Unconditioned.

301

Werenfels in Mr. Mansel's Bampton Lectures, lect. ii. Note 15.

302

Scholium Generale at the end of the Principia.

303

B. iv. c. i.

304

Reid's Works, Supplementary Dissertation D.

305

Hist. Sc. Id. b. iii.

306

Hist. Sc. Id. b. vi. c. iii.

307

The remarks contained in this chapter have for the most part been already printed and circulated in a Letter to the Author of Prolegomena Logica, 1852.

308

Biographical History of Philosophy, 1846. In a more recent edition the author of this work has modified his expressions, but still employs himself in arguing against Dr. Whewell, in order to overthrow Kant. So far as his arguments affect my philosophy, they are, as I conceive, answered in the various expositions which I have given of that philosophy.

309

B. ii. The Philosophy of the Pure Sciences. Chap. ii. Of the Idea of Space. Chap. iii. Of some peculiarities of the Idea of Space. Chap. vii. Of the Idea of Time. Chap. viii. Of some peculiarities of the Idea of Time.

310

Prolegomena Logica, by H. L. Mansel, M.A. 1851.

311

Logic, i p. 273, 3rd edit.

312

No. 193, p. 29.

313

Prol. Log. p. 123.

314

See Phil. Ind. Sc. b. vi. c. iii.

315

Kant.

316

Republished as The History of Scientific Ideas.

317

Given in the Novum Organon Renovatum.

318

Nov. Org. Ren. Aph. cv.

319

Hist. Sc. Id. b. ix. c. vi.

320

Hist. Ind. Sc. b. xviii. c. vi. sect. 5

321

P. 116. "No amount of human knowledge can be adequate which does not solve the phenomena of these absolute certainties."

322

Prof. Butler, Lect. ix. Second Series, p. 136, appears to think that Plato had sufficient grounds (of a theological kind) for the assumption of such Ideas; but I see no trace of them.

323

I am aware that this translation is different from the common translation. It appears to me to be consistent with the habit of the Greek language. It slightly leans in favour of my view; but I do not conceive that the argument would be perceptibly weaker, if the common interpretation were adopted.

324

In the First Alcibiades, Pythodorus is mentioned as having paid 100 minæ to Zeno for his instructions (119 A).

325

P. 183 e.

326

Deip. xi. c. 15, p. 105.

327

Accedit et illud quod naturalis philosophia in iis ipsis viris, qui ei incubuerunt, vacantem et integrum hominem, præsertim his recentioribus temporibus, vix nacta sit; nisi forte quis monachi alicujus in cellula, aut nobilis in villula lucubrantis, exemplum adduxerit; sed facta est demum naturalis philosophia instar transitus cujusdam et pontisternii ad alia. Atque magna ista scientiarum mater ad officia ancillæ detrusa est; quæ medicinæ aut mathematicis operibus ministrat, et rursus quæ adolescentium immatura ingenia lavat et imbuat velut tinctura quadam prima, ut aliam postea felicius et commodius excipiant.

328

μεταξὺ οἰκονομίας καὶ χρεματισμοῦ, between house-keeping and money-getting.

329

τὸ περὶ τοὺς λόγους.

330

The Sciences are to draw the mind from that which grows and perishes to that which really is: μάθημα ψυχῆς ὁλκὸν ἀπὸ τοῦ γιγνομένου ἐπι τὸ ὅν.

331

ἐπὶ θέαν τῆς τῶν ἀριθμῶν φύσεως.

332

τῇ νοηήσει αὐτῇ.

333

He adds "and for the sake of war;" this point I have passed by. Plato does not really ascribe much weight to this use of Science, as we see in what he says of Geometry and Astronomy.

334

ἀρθῶς ἕχει ἑξῆς μετὰ δευτέραν αὕξην τρίτην λαμβάνειν, ἕστι δέ που τοῦτο περὶ τὴν τῶν κύβων αύξην καὶ τὸ βάθους μέτεχον.

335

ἀντίστροφον αὐτοῦ.

336

πρὸς ἐναρμόνιον φορὰν ὦτα παγῆναι.

337

πυκνώματα ἄ ττα.

338

τίνες ξύμφωνοι ἀριθμοὶ, &c.

339

Η καὶ διαλεκτικὸν καλεῖς τὸν λόγον ἐκάστου λαμβάνοντα τῆς οὐσίας; (§ 14).

340

ὥσπερ θριγγὸς τοῖς μαθήμασιν ἡ διαλεκτικὴ ἦμιν ἐπάνω κεῖσθαι. (§ 14).]

341

Pol. vi. § 19.

342

He adds, "This oraton, this visible world, I will not say has any connexion with ouranon, heaven, that I may not be accused of playing upon words."

343

It is plain that Plato, by Hypotheses, in this place, means the usual foundations of Arithmetic and Geometry; namely, Definitions and Postulates. He says that "the arithmeticians and geometers take as hypotheses (hυποθεμενοι) odd and even, and the three kinds of angles (right, acute, and obtuse); and figures, (as a triangle, a square,) and the like." I say his "hypotheses" are the Definitions and Postulates, not the Axioms: for the Axioms of Arithmetic and Geometry belong to the Higher Faculty, which ascends to First Principles. But this Faculty operates rather in using these axioms than in enunciating them. It knows them implicitly rather than expresses them explicitly.

344

διάνοιαν άλλ' οὐ νοῦν.

345

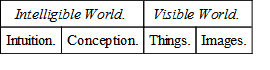

The Diagram, as here described, would be this:

Plato supposes the whole, and each of the two parts, to be divided in the same ratio, in order that the analogy of the division in each case may be represented.

346

The four segments might be as 4: 2: 2: 1; or as 9: 6: 6: 4; or generally, as a: ar: ar: ar2.

347

Hence the mind Reason receivesIntuitive or Discursive.Milton.348

τῇ τοῦ διαλέγεσθαι δυνόμει.

349

This term occurs in other parts of Aristotle. See the additional Note.

350

Mr. Owen, to whom I am indebted for the physiological part of this criticism, tells me, "All mammalia have bile, the carnivora in greater proportion than the herbivora: the gall-bladder is a comparatively unimportant accessory to the biliary apparatus; adjusting it to certain modifications of stomach and intestine: there is no relation between natural longevity and bile. Neither has the presence or absence of the gall-bladder any connexion with age. Man and the elephant are perhaps for their size the longest lived animals, and the latest at coming to maturity: one has the gall-bladder, and the other not."

351

Hist. Sc. Ind. b. iii.

352

These remarks were written in 1841. The accompanying Memoir contains a further discussion of this problem.

353

Cartes. Princip. iv. 23.

354

Jac. Bernoulli, Nouvelles Pensées sur le Système de M. Descartes, op. t. i. p. 239 (1686).

355

De la Cause de la Pesanteur (1689), p. 135.

356

Journal des Savans, 1703. Mém. Acad. Par. 1709.

Bulfinger, in 1726 (Acad. Petrop.), conceived that by making a sphere revolve at the same time about two axes at right angles to each other, every particle would describe a great circle; but this is not so.

357

Acad. Par. 1714, Hist. p. 106.

358

Acad. Par. 1733.

359

Acad. Sc. 1709. If we abandon the clear principles of mechanics, the writer says, "toute la lumière que nous pouvons avoir est éteinte, et nous voilà replongés de nouveau dans les anciennes ténèbres du Peripatetisme, dont le Ciel nous veuille preserver!"

It was also objected to the Newtonian system, that it did not account for the remarkable facts, that all the motions of the primary planets, all the motions of the satellites, and all the motions of rotation, including that of the sun, are in the same direction, and nearly in the same plane; facts which have been urged by Laplace as so strongly recommending the Nebular Hypothesis; and that hypothesis is, in truth, a hypothesis of vortices respecting the origin of the system of the world.

360

Nouvelle Physique Céleste, Op. t. iii. p. 163.

The deviation of the orbits of the planets from the plane of the sun's equator was of course a difficulty in the system which supposed that they were carried round by the vortices which the sun's rotation caused, or at least rendered evident. Bernoulli's explanation consists in supposing the planets to have a sort of leeway (dérive des vaisseaux) in the stream of the vortex.

361

See Hist. Sc. Ideas, b. iii. c. ix. Art. 7.

362

See Mill's Logic, vol. i. p. 311, 2nd ed.

363

These letters refer to passages in the Translation annexed to this Memoir.