полная версия

полная версияVondel's Lucifer

Joost van den Vondel

Vondel's Lucifer

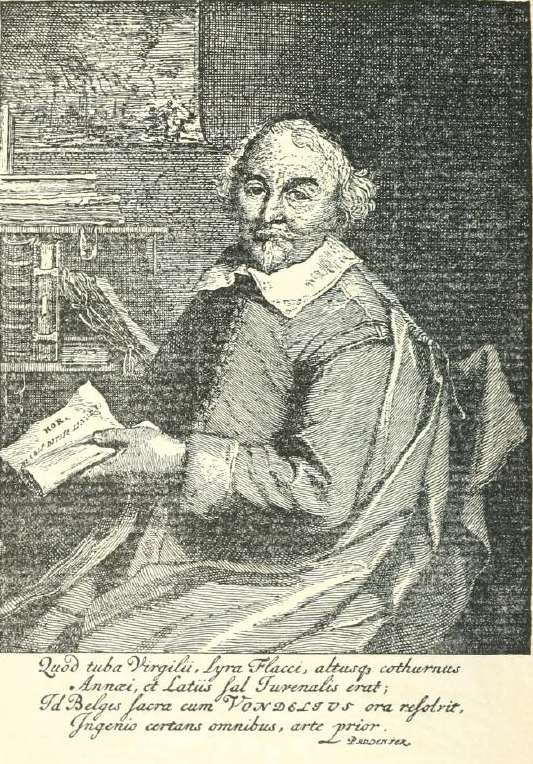

Vondel.

Translator's Preface

It is with a feeling of diffidence that I offer to American readers this the first English version of that unknown Titan, Vondel, a poet of whom Southey's words on Bilderdÿk, another Dutch bard, might also have been spoken:

"The language of a stateInferior in illustrious deeds to none,But circumscribed by narrow bounds,…Hath pent within its sphere a name wherewithEurope should else have rung from side to side."This translation of the "Lucifer" is the result of years of careful study, and I may therefore be pardoned for calling it a conscientious effort. My object has been to give merely a literal but sympathetic rendering. It has been my aim to preserve the old poet in all his rugged simplicity, for every syllable of this classic has been hallowed by centuries. It is sacred, and every change is but a desecration.

Sacred as is the body of such a poem, yet how much holier is its spirit—the elusive properties of its soul! But how seldom does the translation of a great classic prove other than the breaking of the chalice and the spilling of the wine! Yet if but some faint aroma of its original beauty linger around the fragment of this offering—this version of Vondel's grand drama—I lay down my pen content.

I am aware that less accuracy and a greater freedom might in many places have produced a more ornate and highly finished rendering; but this, it seems to me, would have weakened a poem—a poem whose chief merit is its remarkable virility. Every word in a translation of a classic, not in the original, is but the alloy that lessens the proportion of true gold in the coin of its worth. Felicitous paraphrasing is often only a confession of inability to translate an author into the true terms of poetical equation. Mere prettinesses are surely not to be expected in a poem so sublime and stately. I have therefore followed the text of the original very closely.

The body of the drama was written by Vondel in rimed Alexandrines. This part of the play I have rendered into blank verse—a metrical form far better suited to the English drama, and also more adapted to the genius of our language. It is obvious, too, that this admits of much greater accuracy in the translation.

I have, however, scrupulously adhered to the original metres of all the choruses—most of them very involved and intricate, some modelled after the antique—even to preserving the feminine and interior rimes; for the utility and beauty of the chorus is in its music, and the music consists in both metre and rime. I have also generally followed Vondel's capitalization and punctuation, and his spelling of the names of the characters, as Belzebub, Rafael, Apollion, etc.

With the much discussed question of Milton's indebtedness to Vondel this effort has nothing to do. I mention this merely to show that this version was not made that it might be adduced as proof of Vondel's influence on his great English contemporary. It has a much higher reason to commend it; namely, the intrinsic value of the original as a poem and as a national masterpiece. My desire has been to give Vondel; and Vondel is a sufficient justification.

At the same time, I was not displeased when I received a letter from a distinguished American scholar, stating that this translation also incidentally fills a wide gap in the Miltonic criticism, and that it thus supplies a great desideratum.

With this version of Vondel's masterpiece I have also been asked to give a sketch of the poet and his time, and an interpretation of the drama, since there is so little in English on the subject.

In writing the former, I found much of value in Mr. Gosse's charming essays on Vondel, in his "Northern Studies." I must also acknowledge my great obligations to Dr. Kalff's "Life of Vondel."

Before closing I wish to thank the poets and scholars of the Netherlands for their encouragement. Their kind reception of my effort was a gratifying surprise to me.

I must also take this opportunity to record the kindness of that eminent scholar, Dr. G. Kalff, Professor of Dutch Literature in the University of Utrecht, who, though overwhelmed with professional duties, with the most painstaking care examined every part of my translation, giving me, furthermore, the benefit of his critical observations. The brilliant article on Vondel and his "Lucifer," with which he has favored this volume, is an added reason for my gratitude.

I also thank Dr. W.H. Carpenter of Columbia University for his kind interest in my work, and for his invaluable introduction.

And, finally, to my friends, Prof. Henry Jerome Stockard, the Southern poet; Dr. Thomas Hume, Professor of English Literature in the University of North Carolina; and Dr. C. Alphonso Smith, Professor of English in the University of Louisiana, I also express my thanks for some excellent suggestions.

Introduction

Vondel's Lucifer in EnglishIt has become a matter of literary tradition, in Holland and out of it, that the choral drama of "Lucifer" is the great masterpiece of Dutch literature. The Dutch critics, however, are by no manner of means unanimous in this opinion. In point of fact, it has been assigned by some a place relatively subordinate among the works of this "Dutch Shakespeare," as they are fond of calling Vondel at home. No other one, however, in the long list of his dramas and poems, from the "Pascha" of 1612 to his last translations of 1671, the beginning and the end of a literary career, in which one of the greatest of Dutch writers on its history has pronounced the poetry of the Netherlands to have attained its zenith, will, none the less, so strongly appeal to us, outside of Holland, as does the "Lucifer." Vondel's tragedy "Gysbreght van Amstel" may have found far greater favor as a drama, and the poet may possibly in his lyrics have risen to his greatest height; but neither the one nor the other, in spite of this, can have such supreme claims upon our attention.

Why this is so is dependent upon a variety of reasons. It is not solely on account of the lofty character of the subject, nor because we have an almost identical one in a great poem in English literature, between which and the "Lucifer" there is a more than generic resemblance. The question of Milton's indebtedness to Vondel is no longer to be considered an open one, and has resolved itself into an inquiry simply as to the amount of the influence exerted. This is an interesting phase of the matter, and, since it involves one of our great classics, an important one. The two poems, nevertheless, however great this influence may be shown to be, are by no manner of means alike in detail, and one main source of interest to us, to whom "Paradise Lost" is a heritage, is undoubtedly to compare the treatment of such a subject by two great poets of different nationalities. The paramount reason, however, why the "Lucifer" should appeal to us is because it is, in reality, one of the great poems of the world; because of its inherent worth, its seriousness of purpose, the sublimity of its fundamental conceptions, its whole loftiness of tone. When the critics praise others of Vondel's works for excellences not shared by the "Lucifer," they extol him immeasurably, for there is enough in this poem alone to have made its author immortal.

It is a matter of surprise that down to the present time there has been no English translation of "Lucifer," although, after all, its neglect is but a part of the general indifference among us to the literature of Holland in all periods of its history. Why this should be so is not quite apparent; for wholly apart from the important question of action and reaction as a constituent part of the world's literature, the literature of Holland has in it, in almost every phase of its development, sublimities and beauties of its own which surely could not always remain hidden. An era of translation was sure to set in, and it is a matter of significance that its herald has even now appeared.

That the first considerable translation of any Dutch poet into English should be Vondel, and that the particular work rendered should be the "Lucifer," is, from the preëminent place of writer and poem in the literature of the Netherlands, altogether apt.

It is particularly fitting, however, that such an English translation, both because it is first and because it is Vondel, should be put forth, beyond all other places, from this old Dutch city of New York. There is surely more than a passing interest in the thought that, at the time of the appearance of Vondel's "Lucifer" in old Amsterdam, in 1654, its reading public was in part New Amsterdam, as well. Whether any copy of the book ever actually found its way over to the New Netherlands is a matter that it is hardly possible now to determine; but that it might have been read in the vernacular as readily here as at home is a fact of history. Only two years after the publication of the "Lucifer," that is in 1656, Van der Donck, as his title page states, "at the time in New Netherland," printed his "Beschryvinge van Nieuw-Nederlant," in which occurs the familiar picture of "Nieuw Amsterdam op 't Eylant Manhattans," with its fort, and flagstaff, and windmill, its long row of little Dutch houses, and its gibbet well in the foreground as an unmistakable symbol of law and order.

Strikingly enough, too, during the lifetime of Vondel we were making our own contributions to Dutch literature; modest they certainly may have been, but real none the less. Jacob Steendam, the first poet of New York, wrote here at least one of his poems, the "Klagt van Nieuw-Amsterdam," printed in Holland in 1659, and from this same period are the occasional verses of those other Dutch poets, Henricus Selyns, the first settled minister of Brooklyn, and of Nicasius de Sille, first colonial Councillor of State under Governor Stuyvesant. Steendam, after he had returned from these shores to the Fatherland, is still a New Netherlander in spirit, for he continued to sing in vigorous, if homely, verses of the land he had left, which in his long poems, "'T Lof van Nieuw-Nederland," and "Prickel-Vaersen" he paints in glowing colors:

Nieuw-Nederland, gy edelste GewestDaar d'Opperheer (op 't heerlijkst) heeft gevestDe Volheyt van zijn gaven: alder-bestIn alle Leden.Dit is het Land, daar Melk en Honig vloeyd:Dit is't geweest, daar't Kruyd (als dist'len) groeyd:Dit is de Plaats, daar Arons-Roede bloeyd:Dit is het Eden.A translation of Vondel, from what has been said, is, accordingly, in a certain sense, a rehabilitation, a restoration to a former status that through the exigency of events has been lost. While this may be considered from some points of view but a curiosity of coincidence, it is in reality, as has been assumed, much more than that: it is a pertinent reminder of our historical beginnings, a harking back to the century that saw our birth as a province and as a city, to the mother country and to the mother tongue.

Of the literature of Holland, from the lack of opportunity, we know far too little. The translation into English of Vondel's "Lucifer" is not only in and for itself an event of more than ordinary importance in literary history, but it cannot fail to awaken among us a curiosity as to what else of supreme value maybe contained in Dutch literature, and thereby, in effect, form a veritable "open sesame" to unlock its hidden treasures.

WM. H. CARPENTER,

Professor of Germanic Philology,

Columbia University, New York.

NEW YORK, April 4, 1898.

Introduction: Dr. Kalff

When Vondel, in 1653, finished his "Lucifer," he stood, notwithstanding his sixty-six laborious years, with undiminished vigor upon one of the loftiest peaks in his towering career.

A long road lay behind him, in some places rough and steep, though ever tending upwards. What had he not experienced, what had he not endured since that day in 1605 when he contributed a few faulty strophes to a wedding feast—the first product of his art of which we have any knowledge!

After a long and wearisome war, full of brilliant feats of arms, his countrymen had, at length, closed a treaty full of glory to themselves with their powerful and superior adversary. The Republic of the United Netherlands had taken her place among the great powers of the earth. In the East and in the West floated the flag of Holland. Over far-distant seas glided the shadows of Dutch ships, en route to other lands, bearing supplies to satisfy their needs, or speeding homewards freighted with riches.

Prince Maurice was dead. Frederic Henry and William II. had come and gone. De Witt, however, guided the helm of the ship of state; and as long as De Ruyter stood on the quarter-deck of his invincible "Seven Provinces" no reason existed to inspire an Englishman with a "Rule Britannia."

Knowledge soared on daring wings. Art reigned triumphant. The Stadhuis at Amsterdam was nearing completion. Rembrandt's "Night Patrol" already hung in the great hall of the Arquebusiers, and his "Syndics of the Cloth Merchants" was soon to be begun.

Fulness of life, growth of power, and the extension of boundaries were everywhere apparent. The life of the period is like an impressive pageant: in front, proud cavaliers, in high saddles, on their prancing steeds, with splendid colors and dazzling weapons, while silk banners gorgeously embroidered are waving aloft; in the rear, beautiful triumphal chariots and picturesque groups; around stands a clamorous multitude that for one moment forgets its cares in the glow of that splendor, though often only kept in restraint with difficulty.

In the midst of this busy, murmurous scene, Vondel with steady feet pursued his own way; often, indeed, lending his ear to the voices with which the air reverberated, or feasting his eyes upon color and form; often, too, lifting his voice for attack or defence; though still more often with averted glance, and lost in meditation, listening to the voice within.

Life had not left him untried. In many a contest, especially in his struggles against the Calvinistic clergy, he had strengthened his belief on many a doubtful point, developed his powers, and sharpened his understanding.

He had lost two lovely children; his tenderly beloved wife, who lived for him, had left him alone; his conversion to Catholicism had cost him much internal strife, and had brought with it the loss of former friends; his oldest son, Joost, had plunged him into financial difficulties, which resulted in ruin: yet beneath all this his sturdy strength did not fail him.

The fire of his spirit, not suppressed or smothered by the piled-up fuel of early learning, but constantly and richly fed with that which was best, burned with a fierce flame, ever hungry for new food. Treasures of art and knowledge he had gathered, even as the honey-bee culls her store out of all meadows and flowers; for towards art and knowledge his heart ever inclined—towards those muses of whom, in his "Birthday Clock of William Van Nassau," he said:

"For whom all life I love; and without whom, ah me!The glorious majesty of sun I could not gladly see."In an awe-inspiring number of long and short poems, he had, since those first lame verses, developed his art; he had taught his understanding to make use of life-like forms in the construction of his dramas; his feelings he had made deeper and more refined; his taste he had ennobled; his self-restraint he had increased; his technique he had made perfect.

Did his Bible remain the fount from which he preferred to draw the material for his dramas, he also gladly borrowed his motifs from the past of classical antiquity, and from the every-day Netherland life around him. His own fiery belief and deep convictions, and irrepressible desire to give vent to them, caused the person of the poet to be seen more clearly in his characters than we observe to be the case in the productions of his masters, the classic tragedians.

"Palamedes" is a tempestuous defence of the great statesman Oldenbarneveldt—a defence full of intemperate passion, bitter reproach, and burning satire. How fiercely glows there, in each word, in each answer, in transparent allusion and in scornful irony, the fire of party spirit! How often, too, do we there hear the voice of the poet himself, as it trembles with tender sympathy or with lofty indignation!

"Gÿsbrecht van Amstel," a subject dearer to the burghers of Amsterdam than most others, is illuminated with the soft glimmer of altar-candles mingled with airy incense. That same light, that same perfume, we also perceive in "Maeghden," "Peter en Pauwels," and "Maria Stuart."

The Christ-like, humble thankfulness of a Dutch burgher falls upon our ears in the "Leeuwendalers," that charming pastoral, in which the wanton play of whistling pipe and reed is constantly relieved by the silvery pure tones of ringing peace-bells.

Does the history of the development of the Vondelian drama teach us more about the man Vondel, it also most clearly shows us the evolution of the artist. Especially after his translation of "Hippolytus" he had weaned himself from the style of Seneca. More and more he became filled with the grandeur of the Greek tragedians, Sophocles and Euripides above all others. Æschylus he had not yet made his own; that hour was not yet come.

In "Gÿsbrecht van Amstel" we feel, for the first time, that Vondel acknowledges the Greeks as his masters, that he strives to follow them in their sublime simplicity; in their naturalness, that never degenerates to the gross; in their freedom of movement, so different from the stiffness of the school of Seneca; in the exquisitely delicate manner in which the lyric is introduced into the drama. In "Joseph in Dothan," "Leeuwendalers," and "Salomon," we behold the poet pursuing the same path, and here the influence of the Greeks is still more perceptible.

We have attempted in a few rapid strokes to give a brief outline of the time in which the tragedy "Lucifer" had its origin, and also of the man, the poet, who created it.

When Vondel first conceived the plan of writing this tragedy is not known. However, it is well known that this subject had early made an impression upon him. In the collection of prints entitled "Gulden Winkel" (1613), for which Vondel wrote the accompanying mottoes, we already find the Archangel whom God had doomed to the pit of hell. In the "Brieven der Heilige Maeghden" (1642), and in "Henriette Marie t'Amsterdam" (1642), we also find mention of the revolt of the Archangel. In the first-named work the strife between Michael and Lucifer, with their legions, is already seen in prototype. About 1650 he had undoubtedly resolved upon a plan to expand this subject into a tragedy.

Was the fallen Archangel for a long period thus ever present to the poet's eye? Did that subject so enthrall him that, at last, he could no longer resist the impelling desire to picture it after his own fashion? For the causes of this interest we shall not have far to seek.

The seventeenth century was, more than almost any other, the age of authority, and "Lucifer" is the tragedy of the individual in his revolt against authority. Vondel, the Catholic Christian, to whom the ruling power was holy—holy because it came from God; Vondel, the Amsterdam burgher, reared in the fear of the Lord, and full of reverence for those in authority as long as his conscience approved; Vondel must thus have been deeply impressed by the thought of the presumptuous attempt of the Stadholder of God, "the fairest far of all things ever by God created," in his revolt against the "Creator of his glory." Out of this deep agitation this tragedy was born.

Only a genius such as that of Vondel or Milton could bring itself to undertake so dubious a task—out of such material to create a poem; only the highest genius could succeed in such gigantic attempt. Only such a poet can translate us on the mighty wings of his imagination into the portals of heaven; can present to us angels that at the same time are so human that we can put ourselves in their place, but who, nevertheless, remain for us a higher order of beings; can dare to bring into a drama a representation of God, without offending His majesty.

With chaste taste the poet has only rapidly sketched the scene of the drama; by means of a few suggestive strokes, awaking in reader and hearer a sympathetic conception: an illimitable spaciousness radiant with light; an eternal sunshine, more beautiful than that of earth, mirroring itself in the blue crystalline, above which hover hosts of celestial angels; here and there in the background, the dazzling pediments, towers, and battlements of ethereal palaces; far away, upon the heights beyond, the golden port, from which God's "Herald of Mysteries" came down into view. The earth lies immeasurably far below; high, high above, "So deep in boundless realms of light," God reigns upon His throne.

In that endless vast live and move the inhabitants of Heaven in tranquil enjoyment. "Grief never nestled 'neath those joyful eaves" until the creation of man. Pride and envy now awake in the breasts of the angels, and their suffering begins.

Lucifer's passionate pride, which in its outbursts occasionally reminds us of the heroes of Seneca; his dissimulation in the conversation with the rebellious angels; his wretchedness when Rafael has opened his eyes to an appreciation of his position; his obstinate resistance and untamed defiance—all this Vondel has portrayed for us in a masterly manner. Belzebub, more than Lucifer, is the real genius of evil, the wicked one. He is this in his inclination towards subtle mockery and sarcasm; in his hypocrisy; in his wily use of Lucifer's weakness to incite him to destruction; in the art with which he, while himself behind the curtain, directs the course of events.

After the grand overture of the drama, wherein men and angels are placed over against one another, we see how, in the second act, Lucifer comes on the scene, mounted on his battle chariot, excited, embittered; and then the action develops itself in a remarkably even manner. The clouds roll together; more threateningly, more heavily they impend; the light that glows from the towers and battlements of Heaven grows tarnished; the seditious angels gradually lose their lustre; the thunder approaches with dull rumblings; one moment it is stayed, even at the point of outbursting, where Rafael, "oppressed and wan," throws himself appealingly on Lucifer's neck; then it precipitates itself in a terrible storm of strife between desperate rage and the powers above. The fall of man is the sombre afterpiece of this intensely interesting drama.

All of this is discussed in verses that know not their equal in nobility of sound, in fulness and purity of tone, in rapidity of change from tenderness to strength, in wealth of coloring.

Through its opulence and beauty this tragedy holds a unique place in our literature. Only "Adam in Ballingschap" can be placed beside it. Only Vondel can with Vondel be compared. If, however, one should compare this production with the best that has been produced in this kind of poetry by other nations, its splendor remains undimmed; beside the masterpieces of Æschylus, Dante, and Milton, Vondel's maintain an equal place.

To this tragedy and to other works of Vondel and of some of our other poets we proudly point, if strangers ask us in regard to our right to a place in the world's literature. It could, therefore, not be otherwise than that a Netherlander who loves his countrymen should be glad when the bar between his literature and that of the outside world is raised; when other nations are furnished occasion to admire one of our national treasures, and are thereby enabled to have a better knowledge of the character and the significance of our people.

We heartily rejoice over the fact that Vondel's drama has been translated into English by an American for Americans, with whom we Netherlanders have from time immemorial been on a friendly footing. We rejoice, too, that this rendering into a language which is more of a world tongue than our own will also give to Englishmen an opportunity to enjoy Vondel's work.

Were this translation an inferior one, or were it only mediocre, we should have no reason to be glad. Then, surely, it were better that the translation had never been made; for to be unknown is better than to be misknown.