полная версия

полная версияThe Picturesque Antiquities of Spain

The buildings on the north side of the large court stand on the brink of a perpendicular rock, overhanging the faubourg on the Madrid side of Toledo, and commanding right and left the luxuriant vega, to an extent of from forty to fifty miles. Over the highest story of this portion of the building, and forming a continuation of the rock, a Belvidere has been constructed, the roof of which is supported by piers, leaving all the sides open: it forms a promenade of about a hundred feet in length, by twenty-five in width.

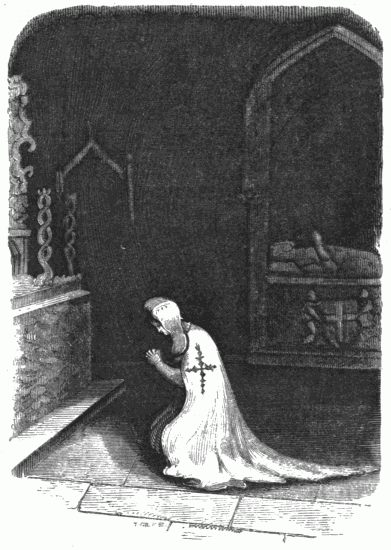

The regulations of this convent are much less strict than those observed by all other religious communities. It would not otherwise have been possible to obtain permission to visit the establishment in detail. The monjas cavalleras (knight-nuns) of the military order of Santiago, take the white veil only, and not the black. If a nun inherits a property, she obtains permission from the council of military orders, sitting at Madrid, to absent herself from the convent for the purpose of transacting all necessary business. The same permission may be obtained in cases of illness. In taking the vows there is no prostration beneath the veil. The novice crosses her hands in a kneeling posture, and takes the oath on the Gospel. One is struck by something invincibly puzzling in this amalgamation of military regulation with religious hierarchy and female seclusion. They call themselves knights; their abbess, commander. The king, as Grand Master of the military orders (since Ferdinand the Fifth) of Calatrava, Alcantara, and Santiago, is their recognised chief; and whenever military mass is required to be performed, the troops march into their chapel to beat of drum.

I was even assured that these recluses are not obliged to refuse a hand offered for a waltz, if it belongs to an arm having an epaulette at its other extremity; and that such scenes are known to occur in the presence of the commandress herself.

Our party, formed for the visit to this convent, having been presented to the superior, she gave directions to a nun to show us every part of the establishment. This sister, who, we were told, bore the title and rank of serjeantess (sargenta), possessed the remains of great beauty, and her (probably) forty summers had not injured her commanding and graceful figure. No sooner had she ushered us into the choir than she left us for an instant, and returned with her mantle of ceremony,—the costume in which they take the vow, and in which they appear on all occasions of solemnity. It was with evident satisfaction that she performed this part of her duties of cicerone; nor was it to be wondered at. No costume could have been invented better calculated to set off her natural advantages. It is composed of a sort of white serge, and appears to have no seam. Attached round the shoulders it sweeps the ground with a train of four or five feet. A cross of scarlet cloth, bound with dark brown edges, and of a graceful form, figures on the portion which covers the left arm from the shoulder to the elbow. The white cap, gathered all over into minute plaits, rises into two parallel ridges, which passing over to the back of the head, imitate the form of a helmet. Two large lappets descend to the shoulders and complete the costume, which is entirely white, with the exception of the cross. In walking round the choir to display to us the effect of this dress, the fair santiagista was a model of majesty and grace.

To judge from her replies to our questions, it would appear that the system of softening the severity of monastic seclusion, and of partial and occasional communication with the beings of the outer world, instead of producing more contentment in the minds of the recluses, may possibly tend to unsettle them, and render them more dissatisfied with their lot. When asked how long she had inhabited the convent, she replied with an unrestrained and most pathetic inflation of the chest, more eloquent than the loudest complaint—"A very long time; nearly twenty years." The white mantle, she told us, was an object the sight of which always gave birth to serious reflections; since it was destined not even to quit her after death, but to serve also for her shroud.

COSTUME OF A MILITARY NUN.

The nun's choir is entirely separated from the public chapel, with the exception of two gratings, which admit to the latter the sound of the organ, and through which the nuns have a better view of the church than the public can obtain of the choir, this being less lighted, and on a lower level. Near the choir a small oratory of no greater dimensions than about seven feet square, appears to be the only remains extant of the Arab buildings, which occupied the site. The ceiling is hemispherical, and ornamented in the Arab style; and one of the walls contains a niche surrounded by Arab tracery. I should mention likewise a fountain in the garden, which bears a similar character.

These nuns live less in community with each other than those of other convents; in fact, their life resembles in many respects that of independent single ladies. Each inhabits her own suite of apartments, and keeps her own servant. Her solitary repasts are prepared in her own separate kitchen, and at the hour chosen by herself. Once a-year only, on the occasion of the festival of the patron Apostle, the community assembles at dinner. The common refectory is at present let to strangers, together with other portions of the convent. The novice who wishes to enter this convent must be of good family, (proof of noble descent being demanded up to grand-fathers and grandmothers inclusive) and possessed of property. Of the entrance of the present commendadora into the convent thirty years since, a romantic story is related. She belongs to a family of rank in the province of La Mancha,—and it is worth mentioning, that she recollects Espartero's father, who, as she states, served a neighbouring family in the capacity of cowherd.

A match, de convenance, had been arranged for her by her parents, on the accomplishment of which they insisted the more rigidly from her being known to entertain an attachment, the object of which was disapproved. No resistance being of any avail, the wedding-day was named; and she was taken to Toledo for the purpose of making the necessary purchases for the occasion. It so happened that she was received by a relative, a member of the community of Santiagistas; and whether she confided her pains to the bosom of this relative, and yielded to her persuasions—nuns being usually given to proselytism; or perhaps acting on the impulse of the moment; she declared on the morning after her arrival her resolution never to quit the convent; preferring, as she resolutely affirmed, an entire life of seclusion, to an union with a man she detested. Instead, therefore, of the wedding dresses, a manton capitular was the only ornament purchased.

The property of this establishment remaining for the most part in possession of the respective original possessors, and not forming a common stock, the conscientious scruples of the revolution made an exception in its favour, owing to which it is not reduced to so destitute a condition as that of the other unclosed convents. The nuns of San Clemente—the principal convent of Toledo, and of which the abbess alone possessed private property, are reduced to a life of much privation, as are also those of all the other convents. Some obtain presents in return for objects of manual industry, such as dolls' chairs, and other similar toys. Those of San Clemente had, and still have, a reputation for superior skill in confectionary. A specimen of their talent, of which I had an opportunity of judging in the house of a friend of the abbess, appeared to me to warrant the full extent of their culinary fame. They do not, however, exercise this art for gain. At San Clemente, and no doubt at all the others, the new government—besides the confiscation of all rents and possessions in money and land—seized the provisions of corn and fruits which they found on searching the attics of the building.

Immediately below the ruined modern Alcazar, and facing the Expositos, is seen a vast quadrangular building, each front of which presents from twenty to thirty windows on a floor. It is without ornament, and is entered by a square doorway, which leads to an interior court. It is now an inn, called Fonda de la Caridad, but was originally the residence of the Cid, who built it simultaneously with the erection of the Alcazar, by Alonzo the Sixth, shortly after the taking of the town; Ruy Diaz being at that time in high favour, and recently appointed first Alcalde of Toledo, and governor of the palace. It was on the occasion of the first cortez held in this town, that the hero demanded a formal audience of Alonzo, in which he claimed justice against his two sons-in-law, the counts of Carrion.

These were two brothers, who had married the two Countesses of Bivar. On the occasion of the double marriage, a brilliant party had assembled at the Cid's residence, where all sorts of festivities had succeeded each other. The two bridegrooms, finding themselves, during their presence in this knightly circle, in positions calculated to test their mettle, instead of proving themselves, by a display of unequalled valour and skill, to be worthy of the choice by which they had been distinguished, gave frequent proofs of deficiency in both qualities; and, long before the breaking up of the party, their cowardice had drawn upon them unequivocal signs of contempt from many of the company, including even their host. Obliged to dissimulate their vexation as long as they remained at the château of the Cid, they concerted a plan of vengeance to be put in execution on their departure.

They took formal leave, and departed with their brides for their estate, followed by a brilliant suite. No sooner, however, had they reached the first town, than, inventing a pretext, they despatched all the attendants by a different route, and proceeded on their journey, only accompanied by their wives. Towards evening the road brought them to a forest, which appeared to offer facilities for putting their project in execution. Here they quitted the highway, and sought a retired situation.

It happened that an attendant of the Countesses, surprised at the determination of the party to divide routes, had been led by curiosity to follow them unobserved. This follower, after having waited some time for their return to the high-road, penetrated into the midst of the wood, in order to discover the cause of the delay. He found the two brides lying on the ground, almost without clothing, and covered with blood, and learned that they had just been left by their husbands, who had been scourging them almost to death.

It was against the perpetrators of this outrage that the Cid pleaded for justice. A certain number of nobles were selected by Alonzo, and directed to give a decision after hearing the accusation and the defence. The offence being proved, the Counts had nothing to urge in extenuation, and judgment was pronounced. All the sums of money, treasures, gold and silver vases and goblets, and precious stones, given by the Cid with his daughters as their dowry, to be restored; and (at the request of Ruy Diaz) the two Counts of Carrion, and their uncle, who had advised them to commit the act, were condemned to enter the lists against three of the followers of the Cid. The last decision was momentarily evaded by the Counts; who urged, that, having come to Toledo to be present at the cortez, they were unprovided with the necessary accoutrements. The King, however, insisted that they should not escape so mild a punishment, and repaired himself to Carrion, where he witnessed the combat, in which, it is needless to add, the culprits came off second best. The marriages being, at the same time, declared null, the Cid's daughters were shortly afterwards married a second time; the eldest, Doña Elvira, to Don Ramiro, son of Sancho, King of Navarre; and the younger, Doña Sol, to Don Pedro, hereditary Prince of Aragon.

LETTER XI.

STREETS OF TOLEDO. EL AMA DE CASA. MONASTERY OF SAN JUAN DE LOS REYES. PALACE OF DON HURTADO DE MENDOZA

Toledo.We will now hasten to the opposite extremity of the city, where the monastery of San Juan de los Reyes lays claim to especial interest. But I already hear you cry for mercy, and exclaim against these endless convents and monasteries; the staircases, courts, and corridors of which cause more fatigue to your imagination, than to the limbs of those who, however laboriously, explore their infinite details. Infinite they are, literally, in Toledo; where the churches, the greater number of which belong to convents, are not seen, as elsewhere, scattered singly among the masses of the habitations, but are frequently to be found in clusters of three or four, whether united by the same walls, or facing each other at the two sides of a street. It may, perhaps, afford you a short relief to pick your way over the somewhat rugged pavement of a few of the Toledo streets, and take a survey of the exterior town, which our present destination requires us to traverse in its entire extent. I must inform you that, for the success of this enterprise, the stranger stands in absolute need of a pilot, without whose assistance his embarrassments would be endless.

Toledo scarcely boasts a street in which two vehicles could meet and continue their route. Most are impassable for a single cart; and, in more than one, I have found it impossible to carry an open umbrella. Such being the prevailing width of the streets, their tortuous direction causes a more serious inconvenience. He who has attempted the task of Theseus, in the mazes of some modern garden labyrinth, will comprehend the almost inevitable consequence of relying on his own wits for finding his way about Toledo,—namely, the discovery that he has returned to his point of departure at the moment he imagined that half the town separated him from it. This result is the more favoured by the similarity of the streets and houses. No such thing as a land-mark. All the convents are alike. You recollect at a particular turning, having observed a Moorish tower; consequently, at the end of the day, the sight of the Moorish tower leads you on, buoyed up by doubly elevated spirits, in the required direction, most anxious to bring the tiring excursion to a close: but this tower leads you to the opposite extremity of the city to that you seek, for there are half a dozen Moorish towers, all alike, or with but a trifling difference in their construction.

Nor is this obstacle to solitary exploration unaccompanied by another inconvenience. I allude to the continual ascents and descents. The surface of the mountain on which Toledo is built, appears to have been ploughed by a hundred earthquakes, so cut and hacked is it, to the exclusion of the smallest extent of level ground. To carry a railroad across it, would require an uninterrupted succession of alternate viaducts and tunnels. In consequence of this peculiarity, the losing one's way occasions much fatigue. To do justice to the inhabitants, an almost universal cleanliness pervades the town,—an excellence the attainment of which is not easy in a city so constructed, and which gives a favourable impression of the population. It is one of the towns in which is proved the possibility of carrying on a successful war against the vermin for which the Peninsula has acquired so bad a reputation, by means of cleanliness maintained in the houses.

In the house I inhabited on my arrival, I had suspected for some days an unusual neglect in the duties of the housemaid, to whose department it belonged to sweep the esteras or matting, which serve for carpets, from the circumstance of my having been visited by one or two unwelcome tormentors. I ventured a gentle remonstrance to the ama (landlady), stating my reasons for the suspicion I entertained. It happened that on the previous day I had mentioned my having been shown over the Archbishop's palace. This she had not forgotten; for with a superb coolness, scarcely to be met with out of Spain, she replied, "Fleas! oh, no! sir! we have none here,—you must have brought them with you from the Palace." Satisfied, however, with having maintained her dignity of landlady, she took care to have the nuisance removed.

This ama, as may be already judged, was a curiosity. In the first place, she was a dwarf. The Spaniards are not, generally speaking, a more diminutive race than the other inhabitants of Southern Europe: but when a Spaniard, especially a woman, takes it into her head to be small, they go beyond other nations. Nowhere are seen such prodigies of exiguity. The lady was, moreover, deformed, one of her legs describing a triangle, which compelled her in walking to imitate the sidelong progress of a crab. Possessed of these peculiarities she had attained, as spinster, that very uncertain age called by some "certain," but agreed by all to be nearer the end than the commencement of life.

Although not an exception, with regard to temper, to the generality of those whose fate it is to endure such a complication of ills, she nevertheless on frequent occasions gave way to much amiability, and especially to much volubility of discourse. She was not without a tinge of sentimentality; and when seated, fan in hand, and the mantilla puesta, on one of the chairs shorn of almost their entire legs, which were to be found in all parts of the house,—she made by no means a bad half-length representation of a fine lady.

She had apparently experienced some of the sorrows and disappointments incident to humanity; and on such occasions had frequently, no doubt, formed the resolution of increasing, although in a trifling degree, some religious sisterhood, of which establishments she had so plentiful a choice in her native city; but, whether on a nearer approach, she had considered the veil an unbecoming costume, or her resolution had failed her on the brink of the living tomb, the project had not as yet taken effect. The turn, however, thus given to her reflections and inquiries, had perfected in her a branch of knowledge highly useful to strangers who might be thrown in her way. She was a limping encyclopedia of the convents and monasteries of Toledo; and could announce each morning, with the precision of an almanack, the name of the saint of the day,—in what church or convent he was especially fêted, and at what hour the ceremony would take place. She was likewise au fait of the foundation, ancient and modern annals, and peculiarities of every sort which belong to every religious establishment of the many scores existing in Toledo. Her administration of the household affairs was admirably organized owing to her energetic activity. Her love of cleanliness would frequently induce her to take the sweeping department into her own hands—a circumstance which was sure to render the operation doubly successful, for the brooms, which in Toledo are not provided with handles or broomsticks, were exactly of a length suited to her stature. Before we take leave of her, here is one more of her original replies.

I complained to her at breakfast that the eggs were not as fresh as usual; and, suiting the action to the word, approached the egg-cup containing the opened one so near to her, that the organs of sight and smell could not but testify to the justice of my reclamation. Shrugging her shoulders, until they almost reached the level of the table—and with much contempt depicted on her countenance: "How could it be otherwise?" she exclaimed, "the egg was taken a quarter of an hour ago from under the hen; but you have broken it at the wrong end."

The monastery called San Juan de los Reyes, was founded by Ferdinand and Isabella, on their return from the conquest of Granada, and given to a fraternity of Franciscan friars. An inscription to this effect in gothic characters runs round the cloister walls, where it forms a sort of frieze, in a line with the capitals of the semi-columns. The inhabited part of the establishment is in a state of complete ruin, having been destroyed by the French during the Peninsular War. The cloisters are, likewise, in a semi-ruinous state: the part best preserved being the church; although that was not entirely spared, as may be supposed from its having been used as cavalry stables.

The choice of a situation for the erection of this convent was perfect in the then flourishing state of Toledo; and, even now, its picturesque position lends a charm to the melancholy and deserted remains still visible of its grandeur and beauty. It stands on the brow of the cliff, commanding the termination of the chasm already described as commencing at the bridge of Alcantara. It commands, therefore, the ruins of Roderick's palace, placed a few hundred yards further on, and on a lower level; still lower the picturesque bridge of St. Martin, striding to the opposite cliff, over arches of ninety feet elevation, and the lovely vega which stretches to the west.

CHURCH OF SAN JUAN DE LOS REYES.

This monastery was one of the most favoured amongst the numerous royal endowments of that period. It is said that its foundation was the result of a vow pronounced by Ferdinand and the Queen before the taking of Granada. In addition to the scale of magnificence adopted throughout the entire plan, the royal founders, on its completion, bestowed a highly venerated donation—the collection of chains taken from the limbs of the Christian captives, rescued by them from the dungeons of the Alhambra. They are suspended on the outside walls of the two sides of the north-eastern angle of the church, and are made to form a frieze, being placed in couples crossing each other at an acute angle; while those that remained are suspended vertically in rows by fours or fives, in the intervals of the pilastres.

The interior of the church is still sufficiently entire to give some idea of its original splendour. Its dimensions are rather more than two hundred feet in length, by eighty in width, and as many in height—excepting over the intersection of the nave and transept, where the ceiling rises to a hundred and eight feet. These dimensions are exclusive of three recesses on either side, forming chapels open to the nave, there being no lateral naves or aisles. The style of the whole is very ornamental; but the east end is adorned with an unusual profusion of sculpture. The transept is separated from the eastern extremity of the building, by a space no greater than would suffice for one of the arches; and its ends form the lines, which being prolonged, constitute the backs of the chapels. The royal arms, supported by spread eagles, are repeated five times on each end-wall; separated respectively by statues of saints in their niches, and surmounted by a profusion of rich tracery. These subjects entirely cover the walls to a height of about forty feet, at which elevation another inscription in honour of the founders runs round the whole interior. The transepts not being formed by open arches, the sides afford space for a repetition of the same ornament, until at their junction with the nave they are terminated by two half-piers covered with tracery, and surmounted by semi-octagonal balconies, beneath which the initials of Ferdinand and Isabella, made to assume a fancy shape, and surmounted by coronets, are introduced with singularly graceful effect.

But the chief attraction of this ruin is the cloister. A small quadrangle is surrounded by an ogival or pointed arcade, enriched with all the ornament that style is capable of receiving. It encloses a garden, which, seen through the airy-web of the surrounding tracery, must have produced in this sunny region a charming effect. At present, one side being in ruins and unroofed, its communication with the other three has been interrupted; and, whether or not in the idea of preserving the other sides from the infection, their arches have been closed nearly to the top by thin plaister walls. Whatever may have been the motive of this arrangement, it answers the useful purpose of concealing from the view a gallery which surmounts the cloister, the arches of which would neutralize the souvenirs created by the rest of the scene, since they announce a far different epoch of art, by the grievous backsliding of taste evinced in their angular form and uncouth proportions.