полная версия

полная версияThe Picturesque Antiquities of Spain

CLOISTER OF SAN JUAN DE LOS REYES, TOLEDO.

Until the destruction of the monastery by the French, the number of monks was very considerable; and in consequence of the unusual privileges accorded to their body, had become the objects of especial veneration. A curious proof of this still exists in the form of a printed paper, pasted on one of the doors in the interior of the church, and no doubt preserved carefully by the fifteen or sixteen brothers, who continued after the dispersion of the rest to inhabit the few apartments, which, by their situation over the cloister, had escaped the flames; and who were only finally compelled to evacuate their retreat on the occasion of the general convent crusade of the late revolution. It is an announcement of indulgences, of which the following is the opening paragraph:—

"Indulgence and days of pardon to be gained by kissing the robe of the brothers of San Francisco.

"All the faithful gain, for each time that they kiss the aforesaid holy robe with devotion of heart, two thousand and seventy-five days of Indulgence. Further than this, whosoever of the faithful shall kiss the aforesaid holy robe devoutly, gains each time eight thousand one hundred days of pardon. The which urges to the exercise of this devotion the Princes, Kings, Emperors, Bishops, and highest dignitaries of the Church, and the monks of other religious orders; and even those of the same order gain the same, according to the doctrine of Lantusca, who writes, 'Videant religiosi quantum thesaurum portent secum.' Since those who with hearts filled with lowliness and love, bend the knees to kiss the precious garment, which opens to so many souls the entrance to Heaven, leading them aside from the paths of perdition, with trembling and terror of the entire hosts of hell, are doubtless those who gain the above-mentioned Indulgences, &c."

Cardinal Ximenes had assumed the habit of this monastery before his nomination to the see of Toledo.

Among the numerous relics of the ancient prosperity of this ruinous corner of Toledo, are seen the walls of the palace of Don Juan Hurtado de Mendoza. To them were confided the secret murmurings of Charles the Fifth's vexation, when, elated with his Italian successes—lord of the greatest empire of Christendom, and flattered by the magnificent hospitality of the Genoese, he only resorted hither to be bearded by his Spanish vassals, and to hear his request for supplies unceremoniously refused. Although monarch of nearly half Europe, and, better still, of Mexico and Peru, that sovereign appears to have undergone the torments of a constantly defective exchequer.

His armies were not numerous for such an empire, and yet they were frequently in revolt for arrears of pay. Could at that time the inventor of a constitution on the modern principle have presented himself to Charles, with what treasures would he not have rewarded him? On his arrival in Spain, in the autumn of 1538, the emperor convoked the cortez in Toledo, "for the purpose of deliberation on the most grave and urgent causes, which obliged him to request of his faithful vassals an inconsiderable contribution, and of receiving the assurance of the desire with which he was animated, of diminishing their burdens as soon as circumstances should enable him to do so." All assembled on the appointed day—the prelates, the grandees, the knights, the deputies of cities and towns. The opening session took place in the great salon of the house of Don Juan Hurtado de Mendoza, Count of Melita, in which the emperor had taken up his abode; and two apartments in the convent of San Juan de los Reyes, were prepared for the remaining meetings—one for the ecclesiastical body, presided by the Cardinal de Tavera, archbishop of Toledo, accompanied by Fray Garcia de Loaysa, cardinal, and confessor of the emperor, afterwards Archbishop of Seville—the other for the lay members of the cortez.

Although an adept at dissimulation, what must have been the impatience of Charles, while under the necessity of listening, day after day, to reports of speeches pronounced by the independent members of his junta on the subject of his unwelcome proposition, without the consolation of foreseeing that the supplies would eventually be forthcoming. The orators did not spare him. The historian, Mariana, gives at full length the speech of the condestable Don Velasco, Duke of Frias, a grandee enjoying one of the highest dignities at the court, who commences by declaring that, "with respect to the Sisa," (tax on provisions, forming the principal subject of the emperor's demand,) "each of their lordships, being such persons as they were, would understand better than himself this business: but what he understood respecting it was, that nothing could be more contrary to God's service, and that of his Majesty, and to the good of these kingdoms of Castile, of which they were natives, and to their honour, than the Sisa;" and, further on, proposes that a request be made to his Majesty, that he would moderate his expenditure, which was greater than that of the Catholic kings.

On an address to this effect being presented to the emperor, he replied, that "he thanked them for their kind intentions; but that his request was for present aid, and not for advice respecting the future:" and finding, at length, that no Sisa was to be obtained, he ordered the archbishop to dissolve the junta, which he did in the following words:—"Gentlemen,—his Majesty says, that he convoked your lordships' assembly for the purpose of communicating to you his necessities, and those of these kingdoms, since it appeared to him that, as they were general, such also should be the remedy; but seeing all that has been done, it appears to him that there is no need of detaining your lordships, but that each of you may go to his house, or whither he may think proper."

It must be confessed that the grandees, who had on this occasion complained of Charles's foreign expeditions, and neglect of his Spanish dominions, did not pursue the system best calculated to reconcile him to a residence among them. Instead of taking advantage of the opportunities afforded by social intercourse, for making amends for the repulse he had suffered from the cortez, they appeared desirous of rendering the amount of humiliation which awaited him in Spain a counterpoise to his triumphs in his other dominions. On the close of the above-mentioned session, a tournament was celebrated in the vega of Toledo. On arriving at the lists, an alguacil of the court, whose duty it was to clear the way on the emperor's approach—seeing the Duke de l'Infantado in the way, requested him to move on, and on his refusal struck his horse with his staff. The duke drew his sword and cut open the officer's head. In the midst of the disturbance occasioned by the incident, the alcalde Ronquillo came up, and attempted to arrest the duke in the emperor's name—when the constable, Duke de Frias, who had just ridden to the scene of bustle, reining in his horse, exclaimed, "I, in virtue of my office, am chief minister of justice in these kingdoms, and the duke is, therefore, my prisoner;" and addressing himself to the alcalde: "know better another time, on what persons you may presume to exercise your authority." The duke left the ground in company of the last speaker, and was followed by all the nobles present, leaving the emperor entirely unaccompanied. It appears that no notice was taken by Charles of this insult; his manner towards the Duke of Infantado on the following day being marked by peculiar condescension, and all compensation to the wounded alguacil left to the duke's generosity.

The personal qualities of this prince, as a monarch, appear to have been overrated in some degree in his own day; but far more so by subsequent writers. The brilliancy of his reign, and the homage which surrounded his person were due to the immense extent of his dominions; and would never have belonged to him, any more than the states of which he was in possession, had their attainment depended in any degree on the exercise of his individual energies. When in the prime of youth, possessed of repeated opportunities of distinguishing himself at the head of his armies, he kept aloof, leaving the entire conduct of the war to his generals. His rival, Francis the First, wounded at Pavia in endeavouring to rally his flying troops, and at length taken prisoner while half crushed beneath his dead horse, was greater—as he stood before the hostile general, his tall figure covered with earth and blood—than the absent emperor, who was waiting at Valladolid for the news of the war.

Nor were the qualities of the statesman more conspicuous than those of the warrior on this occasion. Having received the intelligence of his victory, and of the capture of his illustrious prisoner, he took no measures—gave no orders. To his general every thing was left; and when the captive King was, at his own request, conveyed some time after to Spain, the astonished emperor had received no previous notice of his coming. He allowed himself to be out-manœuvred in the treaty for the liberation of his prisoner; and when Francis broke the pledge he had given for the restitution of Burgundy, he took no steps to enforce the execution of the stipulations; and he ultimately gave up the two French princes, who remained in his power as hostages, in return for a sum of money.

Far from maintaining the superiority in European councils due to his extensive dominions, the Italian republics were only prevented with the greatest difficulty, and by the continual presence of armies, from repeatedly declaring for France: and even the popes, to whom he paid continual court, manifested the small estimation in which they held his influence by constantly deserting his cause in favour of Francis,—the cause of the champion of Christianity in favour of the ally of the Infidel, and that frequently in defiance of good faith; shewing how little they feared the consequences of the imperial displeasure.

If these facts fail in affording testimony to his energy and capacity, still less does his character shine in consistency. He professed an unceasing ardour in the cause of Christianity; offering to the French king the renunciation of his rights, and a release from that monarch's obligations to him, on condition of his joining him in an expedition against the Infidels; but when he found himself at the head of an immense army under the walls of Vienna, he sat still and allowed Solyman to carry off at his leisure the spoils of the principal towns of Hungary.

When at length he made up his mind to take the field, he selected, as most worthy of the exercise of his prowess, the triumph over the pirate Barbarossa and his African hordes: the most important result of the campaign being the occupation of Tunis, (where in his zealous burnings for Christianity he installed a Mahometan sovereign,) and the wanton destruction by his soldiers of a splendid library of valuable manuscripts.

We have seen how little his Spanish subjects allowed themselves to be dazzled by the splendours of his vast authority, and history informs us how far he was from conceiving the resolution of reducing them to obedience by any measures savouring of energetic demonstration. The irreverence to his person he calmly pocketed, and the deficiences in his exchequer were supplied by means of redoubled pressure on his less refractory Flemings. He submitted to the breach of faith of Francis of France, and to the disrespect of his Castilian vassals; but, on the burghers of the city of Ghent being heard to give utterance to expressions of discontent at the immoderate liberties taken with their purse-strings, he quits Madrid in a towering rage, crosses France at the risk of his liberty, and enters his helpless burg at the head of a German army, darting on all sides frowns of imperial wrath, each prophetic of a bloody execution.

Aware of the preparations of Francis for attacking his dominions simultaneously in three different directions, he took insufficient or rather no measures to oppose him, but turning his back, embarked for Algiers, where he believed laurels to be as cheap as at Tunis. There, however, he lost one half of his armament, destroyed by the elements; and the remainder narrowly escaping a similar fate, and being dispersed in all directions, he returned in time to witness the unopposed execution of the plans of his French enemy. What measures are his on such an emergency? Does he call together the contingents of the German States? Unite the different corps serving in Lombardy and Savoy,—dispatch an order to the viceroy of Naples to march for the north of Italy; and having completed his combinations, cross the Pyrenees at the head of a Spanish army, and give the law to his far weaker antagonist? No! nothing that could lead to an encounter with the French king accorded with his policy, as it has been called, but more probably with his disposition. He quits Spain, it is true, and using all diligence, travels round France, but not too near it, and arrives in Flanders. Here he puts himself at the head of his Germans, and marches—against the Duke of Cleves! who had formed an alliance with his principal enemy.

Seeing the emperor thus engaged, Francis completes a successful campaign, taking possession of Luxembourg and other towns. At length the sovereign of half Europe, having received news of the landing of an English army in Picardy, resolves to venture a demonstration against France. He therefore traverses Lorraine at the head of eighty thousand troops, and makes himself master of Luneville: after which, hearing that Francis had despatched his best troops to oppose Henry the Eighth, and was waiting for himself, as the less dangerous foe, with an army of half the strength of his own, and composed of recruits, he makes up his mind to advance in the direction of Paris. After a fortnight's march he finds himself in presence of the French king, to whom he sends proposals of peace!

These being rejected, he continues his march; when a messenger from Francis announces his consent to treat. Under these circumstances, does he require the cession of Burgundy, according to the terms of the unexecuted treaty of Madrid? Does he even stipulate for any advantage, for any equality? No! he agrees, on the contrary, to cede Flanders to the French, under colour of a dowry with his daughter the Infanta Maria, who was to be married to the Duke of Orleans; or else Milan, with his niece the daughter of the King of the Romans; and he beats a retreat with his immense army, as if taking the benefit of a capitulation.

There is something in the result of this French campaign which appears to explain much of Charles's previous conduct; and shows that in many instances he was actuated by personal fear of his gallant rival. On this occasion he did not hesitate to desert the King of England, who had no doubt calculated on his coöperation, as much as Charles had depended on the diversion created by the British army. The more one reflects on the passages of this emperor's history, the less one is surprised at his resolution to abdicate. He gave in this a proof of his appreciation of his real character, which undoubtedly fitted him rather for a life of ease and retirement, than for the arduous duties of supreme power.

LETTER XII.

ARAB MONUMENTS. PICTURES. THE PRINCESS GALIANA. ENVIRONS

Toledo.Returning along the edge of the cliff, a very short space separates the extreme walls of the ruined monastery of Ferdinand and Isabella, from an edifice of much greater antiquity, although not yet a ruin. Its exterior as you approach, is more than simple. It is not even a neatly constructed building; but such a pile of rough looking mud and stone, as, on the continent, announces sometimes a barn, or granary of a farming establishment mal monté. A high central portion runs from end to end, from either side of which, at about four-fifths of its height, project lower roofs of brownish-red tiles. The old square rotten door is in exact keeping with all this exterior, and contributes its share to the surprise experienced on entering, when you discover, on a level with the eye, distributed over a spacious quadrangular area, a forest of elaborately carved capitals, surmounting octagon-shaped pillars, and supporting innumerable horse-shoe arches, scattered in apparent confusion. All these as you advance down a flight of steps, fall into rank, and you speedily find yourself in the centre of an oriental temple in all its symmetry.

INTERIOR OF SANTA MARIA LA BLANCA, TOLEDO.

The principal light entering from the western extremity, you do not at first perceive that three of the five naves terminate at the opposite end, by half domes of more modern invention. These have since been almost built out, and do not form a part of the general view,—not in consequence of a decree of a committee of fine arts, but for the convenience of the intendant of the province, who selected the edifice, as long as it remained sufficiently weather-proof for such a purpose, for a magazine of government stores. There is no record of the antiquity of this church, supposed to be the most ancient in Toledo: at all events, it is the most ancient of those constructed by the Arabs. It was originally a synagogue, and received the above mentioned half cupolas on its conversion to a Catholic church; since which period it has been known by its present title of Santa Maria la Blanca.

A few hundred yards further on, following the same direction, is the church called the Transito, also in the oriental style, but on a different plan: a large quadrangular room, from about ninety to a hundred feet in length, by forty in width, and about seventy high, without arches or columns, ornamented with Arab tracery in stucco, on the upper part of the walls, and by a handsome cedar roof. A cement of a different colour from the rest runs round the lowest portion of the walls, up to about breast high; no doubt filling the space formerly occupied by the azulejos. Some remains of these still decorate the seats, which are attached to the walls at the two sides of the altar. The building is in excellent preservation, and until lately was used as a church of the Mozarabic sect. The ornaments are remarkable for the exquisite beauty of their design, and are uninjured, excepting by the eternal whitewash, the monomania of modern Spanish decorators.

The Jews were the primitive occupants of this elegant temple also. Samuel Levi, treasurer and favourite of Pedro the Cruel (who subsequently transferred his affection from the person of his faithful servant to the enormous wealth, amassed under so indulgent a prince, and seized a pretext for ordering his execution) was the founder of this synagogue. The inauguration was accompanied by extraordinary pomp. The treasurer being, from his paramount position at the court of Castile, the most influential personage of his tribe, the leading members of Judaism flocked from all parts of Europe to Toledo to be present on the occasion, and a deputation from Jerusalem brought earth of the Holy Land, which was laid down throughout the whole interior before the placing of the pavement.

A very different origin, more suited to believers in miracles, is attributed to this church by the present titular sacristan. This Quasimodo of the fabric, a simple and worthy functionary, enjoys a sinecure, except, it is to be feared, with regard to salary. Although, however, no duties confine him to his post, his attachment to the edifice prevents his ever being found further from it than the porch; under the cool shelter of which, as he leans against the wall, he fabricates and consumes the friendly cigarito. When questioned with an appearance of interest on the subject of the building, he replies with unrestrained delight. Its foundation he attributes to Noah, fixing the date at seventeen hundred years back; but without adding any particulars relative to this miraculous visit paid to Toledo, by the ghost of the patriarch.

As is the case with all other ecclesiastical edifices closed pursuant to the recent decrees, this building may become the property of any one, who would offer a sufficient price, not according to the real value, but to that to which such objects are reduced by the great number in the market. Several other churches are simply closed and left unguarded; but the antiquarian sacristan above mentioned, is placed here on account of the existence of a room in which are contained the archives of the knights of Calatrava and Alcantara, until recently its proprietors. No reparations, however, are ordered; and there is many an enthusiast in archæological research who, should such an edifice fall under his notice, would, no doubt, rescue it from its now imminent fate. It is not only a monument admirable for the details of the ornaments, the best of its sort to be met with north of Andalucia, but it forms a valuable link in the chain of architectural history. It is the first ecclesiastical edifice of its style recorded as having set the example of an open area, destitute of columns and arcades.

At the distance of a few hundred yards from this building, a portion of the precipice is pointed out, to which was given in former times the name of the Tarpeian rock. It was the spot selected by the Jewish authorities, (who enjoyed in Toledo, under the Kings of Castile, the right of separate jurisdiction in their tribe,) for the execution of their criminals. It is a perpendicular rock, but with an intermediate sloping space between its base and the Tagus.

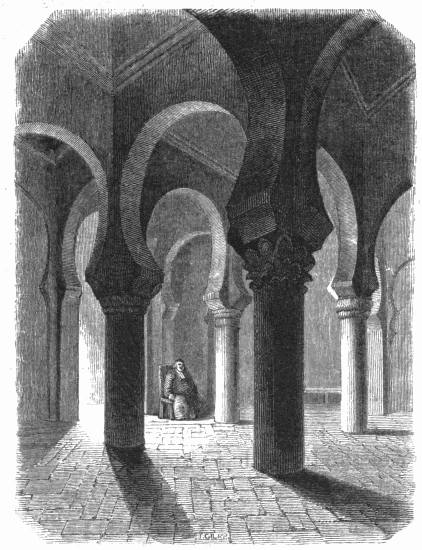

One of the most curious of the Arab monuments of Toledo, is the church called the Christo de la Luz, formerly a mosque. It is extremely small; a square of about twenty feet; and is divided by four pillars into three naves, connected with each other, and with the surrounding walls, by twelve arches. This disposition produces in the ceiling nine square compartments, which rise each to a considerable height, enclosed by walls from the tops of the arches upwards. Each small square ceiling is coved and ornamented with high angular ribs, rising from the cornice and intersecting each other, so as to form a different combination in each of the nine.

INTERIOR OF CHRISTO DE LA LUZ. TOLEDO.

The principal remaining Arab buildings are, the beautiful gate called Puerta del Sol; part of the town walls with their towers; the parochial church of San Roman; the tower of the church of St. Thomas; and two or three other similar towers. Several private houses contain single rooms of the same architecture, more or less ornamental. The most considerable of these is situated opposite the church of San Roman, and belongs to a family residing at Talavera. They have quitted the house in Toledo, which is in a ruinous state. The Moorish saloon is a fine room of about sixty feet in length by upwards of forty high, and beautifully ornamented. The Artesonado roof of cedar lets in already, in more than one part, light and water; and half the remainder of the house has fallen.

The good pictures in Toledo are not very plentiful. It is said some of the convents possessed good collections, which were seized, together with all their other property. Many of these are to be seen in the gallery called the Museo Nacional, at Madrid. Others have been sold. Those of the cathedral have not been removed; but they are not numerous: among them is a St. Francisco, by Zurbaran; and a still more beautiful work of Alonzo del Arco, a St. Joseph bearing the Infant. It is in a marble frame fixed in the wall, and too high to be properly viewed: but the superiority of the colouring can be appreciated, and the excellence of the head of the saint. In the smaller sacristy are two pictures in Bassano's style, and some copies from Raphael, Rubens, and others. At the head of the great sacristy, there is a large work of Domenico Theotocopuli, commonly called El Greco, (the head of the school of Toledo) which I prefer much to the famous Funeral of the Count Orgaz, in the church of Santo Tonie, which, according to some, passes for his masterpiece. In the first are traits of drawing, which forcibly call to mind the style of the best masters of the Roman school, and prove the obligation he was under to the instructions of his master Michel Angelo. The subject is the Calvary. The soldiery fill the back ground. On the right hand the foreground is occupied by an executioner preparing the cross, and on the left, by the group of females. The erect figure of the Christ is the principal object, and occupies the centre, somewhat removed from the front. This is certainly a fine picture; the composition is good, and the drawing admirable, but the colouring of the Greco is always unpleasing.