полная версия

полная версияThe Picturesque Antiquities of Spain

It is still more attractive to repair subsequently to the country itself; and from this central, pyramidal summit—elevated by the hand of Nature to a higher level than the rest of the Peninsula; its bare and rugged surface exposed to all the less genial influences of the elements, and crowned by its modern capital, looking down in all directions, like a feudal castle on the fairer and more fertile regions subject to its dominion, and for the protection of which it is there proudly situated,—to take a survey of this extraordinary country, view the localities immortalized by the eventful passages of its history, and muse on its still varying destinies.

Madrid has in fact already experienced threatening symptoms of the insecurity of this feudal tenure, as it were, in virtue of which it enjoys the supreme rank. Having no claim to superiority derived from its commerce, the fertility of its territory, the facility of its means of communication and intercourse with the other parts of the kingdom or with foreign states,—nothing, in fact, but its commanding and central position, and the comparatively recent choice made of it by the sovereigns for a residence; it has seen itself rivalled, and at length surpassed in wealth and enterprize, by Barcelona, and its right to be continued as the seat of government questioned and attacked. Its fall is probably imminent, should some remedy not be applied before the intermittent revolutionary fever, which has taken possession of the country, makes further advances, or puts on chronic symptoms; but its fate will be shared by the power to which it owes its creation. No residence in Europe bears a prouder and more monarchical aspect than Madrid, nor is better suited for the abode of the feudal pomp and etiquette of the most magnificent—in its day—of European courts: but riding and country sports have crossed the Channel, and are endeavouring to take root in France; fresco-painting has invaded England; in Sicily marble porticoes have been painted to imitate red bricks; and a Constitutional monarchy is being erected in Spain. Spaniards are not imitators, and cannot change their nature, although red bricks should become the materials of Italian palazzi, Frenchmen ride after fox-hounds, and Englishmen be metamorphosed to Michael Angelos. The Alcazar of Madrid, commanding from its windows thirty miles of royal domains, including the Escorial and several other royal residences, is not destined to become the abode of a monarch paid to receive directions from a loquacious and corrupt house of deputies,—the utmost result to be obtained from forcing on states a form of government unsuited to their character. If the Spanish reigning family, after having settled their quarrel with regard to the succession, (if ever they do so,) are compelled to accept a (so-called) Constitutional form of government, with their knowledge of the impossibility of its successful operation, they will probably endeavour, in imitation of the highly gifted sovereign of their neighbours, to stifle it, and to administrate in spite of it; until, either wanting the talent and energy necessary for the maintenance of this false position, or their subjects, as may be expected, getting impatient at finding themselves mystified, a total overthrow will terminate the experiment.

I am aware of the criticism to which this opinion would be exposed in many quarters; I already hear the contemptuous upbraidings, similar to those with which the "exquisite," exulting in an unexceptionable wardrobe, lashes the culprit whose shoulders are guilty of a coat of the previous year's fashion. We are told that the tendency of minds, the progress of intellect, the spirit of the age,—all which, translated into plain language, mean (if they mean anything) the fashion,—require that nations should provide themselves each with a new Liberal government; claiming, in consideration of the fashionable vogue and the expensive nature of the article, its introduction (unlike other British manufactures) duty-free. But it ought first to be established, whether these larger interests of humanity are amenable to the sceptre of so capricious a ruler as the fashion. It appears to me, that nations should be allowed to adapt their government to their respective characters, dispositions, habits of life, and traditions. All these are more dependant than is supposed by those who possess not the habit of reflection, on the race, the position, the soil and climate each has received from nature, which, by the influence they have exercised on their habits and dispositions, have fitted them each for a form of constitution equally appropriate to no other people; since no two nations are similarly circumstanced, not only in all these respects, but even in any one of them.

What could be more Liberal than the monarchy of Spain up to the accession of the Bourbon dynasty? the kings never reigning but by the consent of their subjects, and on the condition of unvarying respect for their privileges; but never, when once seated on the throne, checked and embarrassed in carrying through the measures necessary for the administration of the state. The monarch was a responsible but a free monarch until these days, when an attempt is being made to deprive him both of freedom of action and responsibility—almost of utility, and to render him a tool in the hands of a constantly varying succession of needy advocates or military parvenus, whom the chances of civil war or the gift of declamation have placed in the way of disputing the ministerial salaries, without having been able to furnish either their hearts with the patriotism, or their heads with the capacity, requisite for the useful and upright administration of the empire. In Spain, the advocates of continual change, in most cases in which personal interest is not their moving spring, hope to arrive ultimately at a republic. Now, no one more than myself admires the theories of Constitutional governments, of universal political power and of republicanism: the last system would be the best of all, were it only for the equality it is to establish. But how are men to be equalised by the manufacturers of a government? How are the ignorant and uneducated to be furnished with legislative capacity, or the poor or unprincipled armed against the seductions of bribery? It is not, unfortunately, in any one's power to accomplish these requisite preliminary operations; without the performance of which, these plausible theories will ever lose their credit when brought to the test of experiment. How is a republic to be durable without the previous solution of the problem of the equalisation of human capacities? In some countries it may be almost attained for a time; in others, never put in motion for an instant. No one more than myself abhors tyranny and despotism; but, after hearing and reading all the charges laid at the door of Absolutism during the last quarter of a century, I am at a loss to account for the still greater evils and defects, existing in Constitutional states, having been overlooked in the comparison. The subject is far less free in France than in the absolute states of Germany: and other appropriate comparisons might be made which would bring us still nearer home. I would ask the advocates for putting in practice a republican form of government, and by way of comparing the two extremes, whether all the harm the Emperors of Russia have ever done, or are likely to do until the end of the world,—according to whatever sect the date of that event be calculated,—will not knock under to one week of the exploits of the French republicans of the last century? And if we carry on the observation to the consequences of that revolution, until we arrive at the decimation of that fine country under the military despotism which was necessarily its offspring, we shall not find my argument weakened.

I entreat your pardon for this political digression, which I am as happy to terminate as yourself. I will only add, that, should the period be arrived for the Spanish empire to undergo the lot of all human things—decline and dissolution, it has no right to complain, having had its day; but, should that moment be still distant, let us hope to see that country, so highly favoured by Nature, once more prosperous under the institutions which raised her to the highest level of power and prosperity.

Meanwhile, the elements of discord still exist in a simmering state close to the brim of the cauldron, and a mere spark will suffice at any moment to make them bubble over. The inhabitants of Madrid are in hourly expectation of this spark; and not without reason, if the on-dits which circulate there, and reach to the neighbouring towns, are deserving of credit. Queen Christina, on her road from Paris to resume virtually, if not nominally, the government, conceived the imprudent idea of taking Rome in her way. It is said that she confessed to the Pope, who, in the solemn exercise of his authority as representative of the Deity, declared to her that Spain would never regain tranquillity until the possessions of the clergy should be restored to them.

Whatever else may have passed during the interview is not stated; but a deep impression was produced on the conscience of the Queen, to which is attributed the change in her appearance evident to those who may happen to have seen her a few months since in Paris. This short space of time has produced on her features the effect of years. She has lost her embonpoint, and acquired in its place paleness and wrinkles. She is firmly resolved to carry out the views of the Pope. Here, therefore, is the difficulty. The leading members of her party are among those who have profited largely by the change of proprietorship which these vast possessions have undergone: being the framers or abettors of the decree, they were placed among the nearest for the scramble. In the emptiness of the national treasury, they consider these acquisitions their sole reward for the trouble of conducting the revolution, and are prepared to defend them like tigers.

When, therefore, Queen Christina proposed her plan4 to Narvaez, she met with a flat refusal. He replied, that such a decree would deluge the country with blood. The following day he was advised to give in his resignation. This he refused to do, and another interview took place. The Queen-mother insisted on his acceptance of the embassy to France. He replied, that he certainly would obey her Majesty's commands; but that, in that case, she would not be surprised if he published the act of her marriage with Muños, which was in his power.5 This would compel Christina to refund all the income she has received as widow of Ferdinand the Seventh. The interview ended angrily; and, doubtless, recalled to Christina's recollection the still higher presumption of the man, who owed to her the exalted situation from which, on a former occasion, he levelled his attack on her authority. I am not answerable for the authenticity of these generally received reports; but they prove the unsettled state of things, when the determined disposition of the two opposite parties, and the nearly equal balance of their force, are taken into consideration.

I was scarcely housed at Madrid, having only quitted the hotel the previous day, when the news reached me of the death of one of the fair and accomplished young Countesses—the companions of my journey from Bayonne to Burgos. You would scarcely believe possible the regret this intelligence occasioned me,—more particularly from the peculiar circumstances of the occurrence. Her father had recently arrived from France, and the house was filled for the celebration of her birthday; but she herself was forbidden to join the dinner-party, being scarcely recovered from a severe attack of small-pox. The father's weakness could not deny her admission at dessert, and an ice. The following day she was dead.

Acquaintances made on the high road advance far more rapidly than those formed in the usual formal intercourse of society. I can account in no other way for the tinge of melancholy thrown over the commencement of my sojourn at Madrid by this event,—befalling a person whose society I had only enjoyed during three days, and whom I scarcely expected to see again.

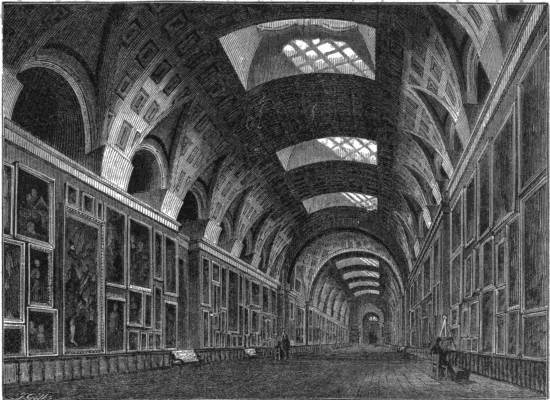

The modern capital of Spain is an elegant and brilliant city, and a very agreeable residence; but for the admirer of the picturesque, or the tourist in search of historical souvenirs, it contains few objects of attraction. The picture-gallery is, however, a splendid exception; and, being the best in the world, compensates, as you may easily suppose, for the deficiency peculiar to Madrid in monuments of architectural interest.

To put an end to the surprise you will experience at the enumeration of such a profusion of chefs d'œuvre of the great masters as is here found, it is necessary to lose sight of the present political situation of Spain, and to transport ourselves to the age of painting. At that time Spain was the most powerful, and especially the most opulent empire in Europe. Almost all Italy belonged to her; a large portion actually owning allegiance to her sceptre, and the remainder being subject to her paramount influence. The familiarity which existed between Charles the Fifth and Titian is well known; as is likewise the anecdote of the pencil, picked up and presented by the Emperor to the artist, who had dropped it.

The same taste for, and patronage of, painting, continued through the successive reigns, until the period when painting itself died a natural death; and anecdotes similar to that of Charles the Fifth are related of Philip the Fourth and Velasquez. All the works of art thus collected, and distributed through the different palaces, have been recently brought together, and placed in an edifice, some time since commenced, and as yet not entirely completed. Titian was the most favoured of all the Italian painters, not only with respect to his familiar intercourse with the Emperor, but also in a professional point of view. The Museo contains no less than forty of his best productions. Nor is it surprising that the taste of the monarch, being formed by his masterpieces, should extend its preference to the rest of the Venetian school in a greater degree than to the remaining Italian schools. There are, however, ten pictures by Raffaelle, including the Spasimo, considered by many to be his greatest work.

A cause similar to that above named enables us to account for the riches assembled in the Dutch and Flemish rooms, among which may be counted more than two hundred pictures of Teniers alone. I should observe, that I am not answerable for this last calculation; being indebted for my information to the director, and distinguished artist, Don Jose Madrazo. There is no catalogue yet drawn up. Rubens has a suite of rooms almost entirely to himself, besides his just portion of the walls of the gallery. The Vandykes and Rembrandts are in great profusion. With regard to the Spanish schools, it may be taken for granted that they are as well represented as those of the foreign, although partially subject, nations. The works of Velasquez are the most numerous; which is accounted for by his situation of painter to the Court, under Philip the Fourth. There are sixty of his paintings.

ITALIAN GALLERY AT THE MUSEO, MADRID.

The Murillos are almost as numerous, and in his best style: but Seville has retained the cream of the genius of her most talented offspring; and even at Madrid, in the collection of the Academy, there is a Murillo—the Saint Elizabeth—superior to any of those in the great gallery. It is much to be wished that some artist, gifted with the pen of a Joshua Reynolds, or even of a Mengs (author of a notice on a small portion of these paintings), could be found, who would undertake a complete critical review of this superb gallery. All I presume to say on the subject is, were the journey ten times longer and more difficult, the view of the Madrid Museo would not be too dearly purchased.

Before I left Madrid, I went to the palace, to see the traces of the conspiracy of the 7th October, remaining on the doors of the Queen's apartments. You will recollect that the revolt of October 1842 was that in favour of Christina, when the three officers, Concha, Leon, and Pezuela, with a battalion, attacked the palace in the night, for the purpose of carrying off the Queen and her sister. On the failure of the attempt, owing to its having been prematurely put in execution, the Brigadier Leon was shot, and the two others escaped.

It appears that the execution of this officer, unlike the greater number of these occurrences, caused a strong sensation in Madrid, owing to the sympathy excited by his popular character, and the impression that he was the victim of jealousy in the mind of the Regent. The fine speech, however, attributed to him by some of the newspapers, was not pronounced by him. His words were very few, and he uttered them in a loud and clear tone, before giving the word of command to his executioners. This, and his receiving the fire without turning his back, were the only incidents worthy of remark.

One of the two sentries stationed at the door of the Queen's anteroom when I arrived, happened to have played a conspicuous part on the eventful night. The Queen was defended by the guard of hallebardiers, which always mounts guard in the interior of the palace. This sentinel informed me that he was on guard that night, on the top step of the staircase, when Leon, followed by a few officers, was seen to come up. Beyond him and his fellow-sentry there were only two more, who were posted at the door of the Queen's anteroom, adjoining her sleeping apartment. This door faces the whole length of the corridor, with which, at a distance of about twenty yards, the top of the staircase communicates. In order to shield himself from the fire of the two sentinels at the Queen's door, Leon grasped my informant by the ribs right and left, and, raising him from the ground, carried him, like a mummy, to the corridor; and there, turning sharp to the left, up to the two sentries, whom he summoned to give him admittance in the name of the absent Christina.

On the soldiers' refusal, he gave orders to his battalion to advance, and a pitched battle took place, which was not ultimately decided until daybreak—seven hours after. The terror of the little princesses, during this night, may be imagined. Two bullets penetrated into the bed-room; and the holes made by about twenty more in the doors of some of the state apartments communicating with the corridor, are still preserved as souvenirs of the event. The palace contains some well-painted ceilings by Mengs, and is worthy of its reputation of one of the finest residences in Europe. The staircase is superb. It was here that Napoleon, entering the palace on the occasion of his visit to Madrid, to install Joseph Buonaparte in his kingdom, stopped on the first landing; and, placing his hand on one of the white marble lions which crouch on the balustrades, turned to Joseph, and exclaimed, "Mon frère, vous serez mieux logé que moi."

There is no road from Madrid to Toledo. On the occasions of religious festivities, which are attended by the court, the journey is performed by way of Aranjuez, from which place a sort of road conducts to the ancient capital of Spain. There is, however, for those who object to add so much to the actual distance, a track, known, in all its sinuosities, throughout its depths and its shallows, around its bays, promontories, islands, and peninsulas—to the driver of the diligence, and to the mounted bearer of the mail; both of whom travel on the same days of the week, in order to furnish reciprocal aid, in case of damage to either. A twenty-four hours' fall of rain renders this track impassable by the usual conveyance; a very unusual sort of carriage is consequently kept in reserve for these occasions, and, as the period of my journey happened to coincide with an uncommonly aqueous disposition of the Castilian skies, I was fortunately enabled to witness the less every day, and more eventful transit, to which this arrangement gave rise.

Accordingly at four o'clock on an April morning—an hour later than is the custom on the road from France to Madrid—I ascended the steps of a carriage, selected for its lightness, which to those who know anything of Continental coach-building, conveys a sufficient idea of its probable solidity. There was not yet sufficient daylight to take a view of this fabric; but I saw, by the aid of a lantern, my luggage lifted into a sort of loose net, composed of straw-ropes, and suspended between the hind wheels in precisely such juxtaposition, as to make the portmanteaus, bags, &c. bear the same topographic relation to the vehicle, as the truffles do to a turkey, or the stuffing to a duck. There was much grumbling about the quantity of my luggage, and some hints thrown out, relative to the additional perils, suspended over our heads, or rather, under our seats, in consequence of the coincidence of the unusual weight, with the bad state of the road, as they termed it, and the acknowledged caducity of the carriage. I really was, in fact, the only one to blame; for I could not discover, besides my things, more than two small valises belonging to all the other six passengers together.

At length we set off, and at a distance of four miles from Madrid, as day began to break, we broke down.

The break-down was neither violent nor dangerous, and was occasioned by the crash of a hind wheel, while our pace did not exceed a walk: but it was productive of some amusement, owing to the position, near the corner of the vehicle which took the greatest fancy to terra firma, of a not over heroic limb of the Castilian law, who had endeavoured to be facetious ever since our departure, and whose countenance now exhibited the most grotesque symptoms of real terror. Never, I am convinced, will those moments be forgotten by that individual, whose vivacity deserted him for the remainder of the journey; and whose attitude and expression, as his extended arms failed to recover his centre of gravity exchanged for the supine, folded-up posture, unavoidable by the occupant at the lowest corner of a broken-down vehicle,—while his thoughts wandered to his absent offspring, whose fond smiles awaited him in Toledo, but to whom perhaps he was not allowed to bid an eternal adieu—will live likewise in the memory of his fellow-travellers.

This dénouement of the adventures of the first carriage rendered a long halt necessary; during which, the postilion returned to Madrid on a mule, and brought us out a second. This proceeding occupied four hours, during which some entered a neighbouring venta, others remained on the road, seated on heaps of stones, and all breakfasted on what provisions they had brought with them, or could procure at the said venta. The sight of the vehicle that now approached, would have been cheaply bought at the price of twenty up-sets. Don Quixote would have charged it, had such an apparition suddenly presented itself to his view. It was called a phaeton, but bore no sort of resemblance to the open carriage known in England by that name. Its form was remarkable by its length being out of all proportion to its width,—so much so as to require three widely-separated windows on each side. These were irregularly placed, instead of being alike on the two sides, for the door appeared to have been forgotten until after the completion of the fabric, and to have taken subsequently the place of a window; which window—pursuant to a praiseworthy sense of justice—was provided for at the expense of a portion of deal board, and some uniformity.

The machine possessed, nevertheless, allowing for its rather exaggerated length, somewhat of the form of an ancient landau; but the roof describing a semicircle, gave it the appearance of having been placed upside down by mistake, in lowering it on to the wheels. Then, with regard to these wheels, they certainly had nothing very extraordinary about their appearance, when motionless; but, on being subjected to a forward or backward impulse, they assumed, respectively, and independently of each other, such a zigzag movement, as would belong to a rotatory, locomotive pendulum, should the progress of mechanics ever attain to so complicated a discovery. Indeed, the machine, in general, appeared desirous of avoiding the monotony attendant on a straight-forward movement; the body of the monster, from the groans, sighs, screams, and other various sounds which accompanied its heaving, pitching, and rolling exertions, appearing to belong to some unwieldy and agonised mammoth and to move by its own laborious efforts, instead of being indebted for its progress to the half-dozen quadrupeds hooked to its front projections.