полная версия

полная версияThe Picturesque Antiquities of Spain

The first of the two judges, Nuño Rasura, was the son of the above-mentioned Nuño Belchides and his wife, Sulla Bella (daughter of Diego Porcellos), and grandfather of Fernan Gonzalez. His son Gonzalo Nuño, Fernan's father, succeeded on his death to the dignity of Judge of Castile, and became extremely popular, owing to his affability, and winning urbanity of deportment in his public character. He established an academy in his palace for the education of the sons of the nobles, who were instructed under his own superintendence in all the accomplishments which could render them distinguished in peace or in war. The maternal grandfather of Fernan Gonzalez was Nuño Fernandez, one of the Counts of Castile who were treacherously seized and put to death by Don Ordoño, King of Leon. The young Count of Castile is described as having been a model of elegance. To singular personal beauty he added an unmatched proficiency in all the exercises then in vogue, principally in arms and equitation. These accomplishments, being added to much affability and good-nature, won him the affections of the young nobles, who strove to imitate his perfections, while they enjoyed the festivities of his palace.

It appears that, notwithstanding the rebellion, and appointment of Judges, Castile had subsequently professed allegiance to the Kings of Leon; for a second revolt was organized in the reign of Don Ramiro, at the head of which we find Fernan Gonzalez. On this occasion, feeling themselves too feeble to resist the royal troops, the rebels had recourse to a Moorish chief, Aecipha. The King, however, speedily drove the Moors across the frontier, and succeeded in capturing the principal revolters. After a short period these were released, on the sole condition of taking the oath of allegiance; and the peace was subsequently sealed by the marriage of a daughter of Gonzalez with Don Ordoño, eldest son of Ramiro, and heir to the kingdom.

The Count of Castile was, however, too powerful a vassal to continue long on peaceable terms with a sovereign, an alliance with whose family had more than ever smoothed the progressive ascent of his pretensions. Soon after the accession of his son-in-law Don Ordoño, he entered into an alliance against him with the King of Navarre. This declaration of hostility was followed by the divorce of Fernan's daughter by the King, who immediately entered into a second wedlock. The successor of this monarch, Don Sancho, surnamed the Fat, was indebted for a large portion of his misfortunes and vicissitudes to the hostility of the Count of Castile. Don Ordoño, the pretender to his throne, son of Alonzo surnamed the Monk, with the aid of Gonzalez, whose daughter Urraca, the repudiated widow of the former sovereign, he married, took easy possession of the kingdom, driving Don Sancho for shelter to the court of his uncle the then King of Navarre. It is worth mentioning, that King Sancho took the opportunity of his temporary expulsion from his states, to visit the court of Abderahman at Cordova, and consult the Arab physicians, whose reputation for skill in the removal of obesity had extended over all Spain. History relates that the treatment they employed was successful, and that Don Sancho, on reascending his throne, had undergone so complete a reduction as to be destitute of all claims to his previously acquired sobriquet.

All these events, and the intervals which separated them, fill a considerable space of time; and the establishment of the exact dates would be a very difficult, if not an impossible, undertaking. Various wars were carried on during this time by Gonzalez, and alliances formed and dissolved. Several more or less successful campaigns are recorded against the Moors of Saragoza, and of other neighbouring states. The alliance with Navarre had not been durable. In 959 Don Garcia, King of that country, fought a battle with Fernan Gonzalez, by whom he was taken prisoner, and detained in Burgos thirteen months. The conquest of the independence of Castile is related in the following manner.

In the year 958, the Cortes of the kingdom were assembled at Leon, whence the King forwarded a special invitation to the Count of Castile, requiring his attendance, and that of the Grandees of the province, for "deliberation on affairs of high importance to the state." Gonzalez, although suspicious of the intentions of the sovereign, unable to devise a suitable pretext for absenting himself, repaired to Leon, attended by a considerable cortége of nobles. The King went forth to receive him; and it is related, that refusing to accept a present, offered by Gonzalez, of a horse and a falcon, both of great value, a price was agreed on; with the condition that, in case the King should not pay the money on the day named in the agreement, for each successive day that should intervene until the payment, the sum should be doubled. Nothing extraordinary took place during the remainder of the visit; and the Count, on his return to Burgos, married Doña Sancha, sister of the King of Navarre.

It is probable that some treachery had been intended against Gonzalez, similar to that put in execution on a like occasion previous to his birth, when the Counts of Castile were seized and put to death in their prison; for, not long after, a second invitation was accepted by the Count, who was now received in a very different manner. On his kneeling to kiss the King's hand, Don Sancho burst forth with a volley of reproaches, and, repulsing him with fury, gave orders for his immediate imprisonment. It is doubtful what fate was reserved for him by the hatred of the Queen-mother, who had instigated the King to the act of treachery, in liquidation of an ancient personal debt of vengeance of her own, had not the Countess of Castile, Doña Sancha, undertaken his liberation.

Upon receiving the news of her husband's imprisonment, she allowed a short period to elapse, in order to mature her plan, and at the same time lull suspicion of her intentions. She then repaired to Leon, on pretext of a pilgrimage to Santiago, on the route to which place Leon is situated. She was received by King Sancho with distinguished honours, and obtained permission to visit her husband, and to pass a night in his prison. The following morning, Gonzalez, taking advantage of early twilight, passed the prison-doors in disguise of the Countess, and, mounting a horse which was in readiness, escaped to Castile.

This exploit of Doña Sancha does not belong to the days of romance and chivalry alone: it reminds us of the still more difficult task, accomplished by the beautiful Winifred, Countess of Nithisdale, who, eight centuries later, effected the escape of the rebel Earl, her husband, from the Tower, in a precisely similar manner; thus rescuing him from the tragic fate of his friends and fellow-prisoners, the Lords Derwentwater and Kenmure.

Doña Sancha obtained her liberty without difficulty, being even complimented by the King on her heroism, and provided with a brilliant escort on her return to Castile. Gonzalez contented himself with claiming the price agreed upon for the horse and falcon; and—the King not seeming inclined to liquidate the debt, which, owing to the long delay, amounted already to an enormous sum, or looking upon it as a pretext for hostility, the absence of which would not prevent the Count of Castile, in his then state of exasperation, from having recourse to arms—passed the frontier of Leon at the head of an army, and, laying waste the country, approached gradually nearer to the capital. At length Don Sancho sent his treasurer to clear up the account, but it was found that the debt exceeded the whole amount of the royal treasure; upon which Gonzalez claimed and obtained, on condition of the withdrawal of his troops, a formal definitive grant of Castile, without reservation, to himself and his descendants.

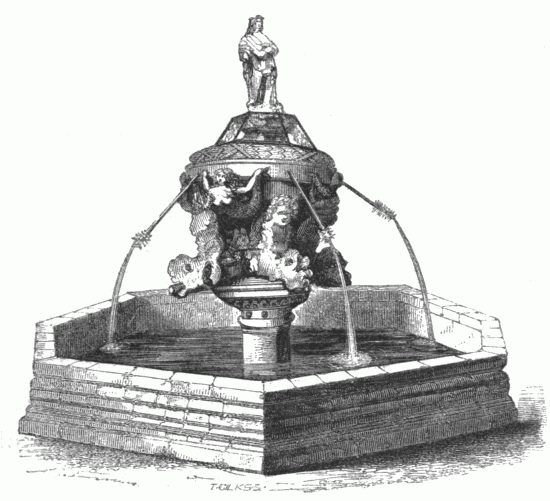

Before we quit Burgos for its environs, one more edifice requires our notice. It is a fountain, occupying the centre of the space which faces the principal front of the cathedral. This little antique monument charms, by the quaint symmetry of its design and proportions, and perhaps even by the terribly mutilated state of the four fragments of Cupids, which, riding on the necks of the same number of animals so maltreated as to render impossible the discovery of their race, form projecting angles, and support the basin on their shoulders. Four mermaids, holding up their tails, so as not to interfere with the operations of the Cupids, ornament the sides of the basin, which are provided with small apertures for the escape of the water; the top being covered by a flat circular stone, carved around its edge. This stone,—a small, elegantly shaped pedestal, which surmounts it,—and the other portions already described, are nearly black, probably from antiquity; but on the pedestal stands a little marble virgin, as white as snow. This antique figure harmonises by its mutilation with the rest, although injured in a smaller degree; and at the same time adds to the charm of the whole, by the contrast of its dazzling whiteness with the dark mass on which it is supported. The whole is balanced on the capital of a pillar, of a most original form, which appears immediately above the surface of a sheet of water enclosed in a large octagonal basin.

FOUNTAIN OF SANTA MARIA.

LETTER VI.

CARTUJA DE MIRAFLORES. CONVENT OF LAS HUELGAS

Burgos.The Chartreuse of Miraflores, situated to the east of the city, half-way in the direction of the above-mentioned monastery of San Pedro de Cardeñas, crowns the brow of an eminence, which, clothed with woods towards its base, slopes gradually until it reaches the river. This spot is the most picturesque to be found in the environs of Burgos,—a region little favoured in that respect. The view, extending right and left, follows the course of the river, until it is bounded on the west by the town, and on the east by a chain of mountains, a branch of the Sierra of Oca. Henry the Third, grandfather of Isabel the Catholic, made choice of this position for the erection of a palace; the only remnant of it now existing is the church, which has since become the inheritance of the Carthusian monks, the successors of its royal founder.

The late revolution, after sparing the throne of Spain, displayed a certain degree of logic, if not in all its acts, at least in sparing, likewise, two or three of the religious establishments, under the protection of which the principal royal mausoleums found shelter and preservation. The great Chartreuse of Xeres contained probably no such palladium, for it was among the first of the condemned: its lands and buildings were confiscated; and its treasures of art, and all portable riches, dispersed, as likewise its inhabitants, in the direction of all the winds.

In England the name of Xeres is only generally known in connection with one of the principal objects of necessity, which furnish the table of the gastronome; but in Andalucia the name of Xeres de la Frontera calls up ideas of a different sort. It is dear to the wanderer in Spain, whose recollections love to repose on its picturesque position, its sunny skies, its delicious fruits, its amiable and lively population, and lastly on its once magnificent monastery, and the treasures of art it contained. The Prior of that monastery has been removed to the Cartuja of Burgos, where he presides over a community, reduced to four monks, who subsist almost entirely on charity. This amiable and gentleman-like individual, in whom the monk has in no degree injured the man of the world,—although a large estate, abandoned for the cloister, proved sufficiently the sincerity of his religious professions,—had well deserved a better fate than to be torn in his old age from his warm Andalucian retreat, and transplanted to the rudest spot in the whole Peninsula, placed at an elevation of more than four thousand feet above the level of the Atlantic, and visited up to the middle of June by snow-storms. At the moment I am writing, this innocent victim of reform is extended on a bed of sickness, having only recently escaped with his life from an attack, during which he was given over.

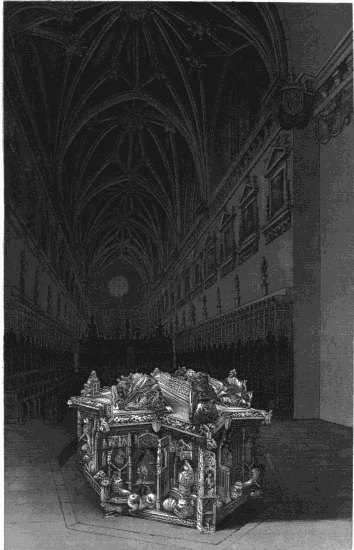

This Cartuja possesses more than the historical reminiscences with which it is connected, to attract the passing tourist. It owes its prolonged existence to the possession of an admirable work of art,—the tomb of Juan the Second and his Queen Isabel, which stands immediately in front of the high altar of the church. This living mass of alabaster, the work of Gil de Siloë, son of the celebrated Diego, presents in its general plan the form of a star. It turns one of its points to the altar. Its mass, or thickness from the ground to the surface, measures about six feet; and this is consequently the height at which are laid the two recumbent figures.

N. A. Wells. deb. W. I. Starling, "84"

INTERIOR OF THE CHURCH OF MIRAFLORES, NEAR BURGOS.

It is impossible to conceive a work more elaborate than the details of the costumes of the King and Queen. The imitation of lace and embroidery, the exquisite delicacy of the hands and features, the infinitely minute carving of the pillows, the architectural railing by which the two statues are separated, the groups of sporting lions and dogs placed against the foot-boards, and the statues of the four Evangelists, seated at the four points of the star which face the cardinal points of the compass,—all these attract first the attention as they occupy the surface; but they are nothing to the profusion of ornament lavished on the sides. The chisel of the artist has followed each retreating and advancing angle of the star, filling the innermost recesses with life and movement. It would be endless to enter into a detailed enumeration of all this. It is composed of lions and lionesses, panthers, dogs,—crouching, lying, sitting, rampant, and standing; of saints, male and female, and personifications of the cardinal virtues. These figures are represented in every variety of posture,—some standing on pedestals, and others seated on beautifully wrought arm-chairs, but all enclosed respectively in the richest Gothic tracery, and under cover of their respective niches. Were there no other object of interest at Burgos, this tomb would well repay the traveller for a halt of a few days, and a country walk.

At the opposite side of the town may be seen the royal convent of Las Huelgas; but as the nuns reserve to themselves the greater part of the church, including the royal tombs, which are said to be very numerous, no one can penetrate to satisfy his curiosity. It is, however, so celebrated an establishment, and of such easy access from the town, that a sight of what portions of the buildings are accessible deserves the effort of the two hundred yards' walk which separates it from the river promenade. This Cistercian convent was founded towards the end of the twelfth century by Alonzo the Eighth,—the same who won the famous battle of the Navas de Tolosa. It occupies the site of the pleasure-grounds of a royal retreat, as is indicated by the name itself. In its origin it was destined for the reception, exclusively, of princesses of the blood royal. It was consequently designed on a scale of peculiar splendour. Of the original buildings, however, only sufficient traces remain to confirm the records of history, but not to convey an adequate idea of their magnificence. What with the depredations of time, the vicissitudes of a situation in the midst of provinces so given to contention, and repeated alterations, it has evidently, as far as regards the portions to a view of which admission can be obtained, yielded almost all claims to identity with its ancient self.

The entire church, with the exception of a small portion partitioned off at the extremity, and containing the high altar, is appropriated to the nuns, and fitted up as a choir. It is very large; the length, of which an estimate may be formed externally, appearing to measure nearly three hundred feet. It is said this edifice contains the tomb of the founder, surrounded by forty others of princesses. The entrance to the public portion consists of a narrow vestibule, in which are several antique tombs. They are of stone, covered with Gothic sculpture, and appear, from the richness of their ornaments, to have belonged also to royalty. They are stowed away, and half built into the wall, as if there had not been room for their reception. The convent is said to contain handsome cloisters, courts, chapter-hall, and other state apartments, all of a construction long subsequent to its foundation. The whole is surrounded by a complete circle of houses, occupied by its various dependants and pensioners. These are enclosed from without by a lofty wall, and face the centre edifice, from which they are separated by a series of large open areas. Their appearance is that of a small town, surrounding a cathedral and palace.

The convent of the Huelgas takes precedence of all others in Spain. The abbess and her successors were invested by the sovereigns of Leon and Castile with especial prerogatives, and with a sort of authority over all convents within those kingdoms. Her possessions were immense, and she enjoyed the sovereign sway over an extensive district, including several convents, thirteen towns, and about fifty villages. In many respects her jurisdiction resembles that of a bishop. The following is the formula which heads her official acts:

"We, Doña …, by the grace of God and of the Holy Apostolic See, Abbess of the royal monastery of Las Huelgas near to the city of Burgos, order of the Cister, habit of our father San Bernardo, Mistress, Superior, Prelate, Mother, and lawful spiritual and temporal Administrator of the said royal monastery, and its hospital called 'the King's Hospital,' and of the convents, churches, and hermitages of its filiation, towns and villages of its jurisdiction, lordship, and vassalage, in virtue of Apostolic bulls and concessions, with all sorts of jurisdiction, proper, almost episcopal, nullius diocesis, and with royal privileges, since we exercise both jurisdictions, as is public and notorious," &c.

The hospital alluded to gives its name to a village, about a quarter of a mile distant, called "Hospital del Rey." This village is still in a sort of feudal dependance on the abbess, and is the only remaining source of revenue to the convent, having been recently restored by a decree of Queen Isabella; for the royal blood flowing in the veins of the present abbess had not exempted her convent from the common confiscation decreed by the revolution. The hospital, situated in the centre of the village, is a handsome edifice. The whole place is surrounded by a wall, similar to that which encloses the convent and its immediate dependances, and the entrance presents a specimen of much architectural beauty. It forms a small quadrangle, ornamented with an elegant arcade, and balustrades of an original design.

LETTER VII.

ROUTE TO MADRID. MUSEO

Toledo.The route from Burgos to Madrid presents few objects of interest. The country is dreary and little cultivated; indeed, much of it is incapable of culture. For those who are unaccustomed to Spanish routes, there may, indeed, be derived some amusement from the inns, of which some very characteristic specimens lie in their way. The Diligence halts for the night at the Venta de Juanilla, a solitary edifice situated at the foot of the last or highest étage of the Somo Sierra, in order to leave the principal ascent for the cool of early dawn. The building is seen from a considerable distance, and looks large; but is found, on nearer approach, to be a straggling edifice of one story only.

It is a modern inn, and differs in some essential points from the ancient Spanish posada,—perfect specimens of which are met with at Briviesca and Burgos. In these the vestibule is at the same time a cow-shed, sheepfold, stable, pigsty,—in fact, a spacious Noah's Ark, in which are found specimens of all living animals, that is, of all sizes, down to the most minute; but for the purification of which it would be requisite that the entire flood should pass within, instead of on its outside. The original ark, moreover, possessed the advantage of windows, the absence of which causes no small embarrassment to those who have to thread so promiscuous a congregation, in order to reach the staircase; once at the summit of which, it must be allowed, one meets with cleanliness, and a certain degree of comfort.

The Venta de Juanilla, on the Somo Sierra, is a newish, clean-looking habitation, especially the interior, where one meets with an excellent supper, and may feast the eyes on the sight of a printed card, hanging on the wall of the dining-room, announcing that luxury of exotic gastronomy—Champagne—at three crowns a bottle: none were bold enough that evening to ask for a specimen.

There is less of the exotic in the bed-room arrangements; in fact, the building appears to have been constructed by the Diligence proprietors to meet the immediate necessity of the occasion. The Madrid road being served by two Diligences, one, leaving the capital, meets at this point, on its first night, the other, which approaches in the contrary direction. In consequence of this arrangement, the edifice is provided with exactly four dormitories,—two male, and two female.

Nor is this the result of an intention to diminish the numbers quartered in each male or female apartment; on the contrary, two rooms would have answered the purpose better than four, but for the inconvenience and confusion which would have arisen from the denizens of the Diligence destined to start at a later hour being aroused from their slumbers, and perhaps induced to depart by mistake, at the signal for calling the travellers belonging to the earlier conveyance,—the one starting at two o'clock in the morning, and the other at three.

On the occasion of my bivouaque in this curious establishment, an English couple, recently married, happened to be among the number of my fellow-sufferers; and the lady's report of the adventures of the female dormitory of our Diligence afforded us sufficient amusement to enliven the breakfast on the other side of the mountain. It appeared, that, during the hustling of the males into their enclosure, a fond mother, moved by Heaven knows what anxious apprehensions, had succeeded in abstracting from the herd her son, a tender youth of fourteen. Whether or not she expected to smuggle, without detection, this contraband article into the female pen we could not determine. If she did, she reckoned somewhat independently of her host; for on a fellow-traveller entering in the dark, and groping about for a considerable time in search of an unoccupied nest, a sudden exclamation aroused the fatigued sleepers, followed by loud complaints against those who had admitted an interloper to this holy of holies of feminine promiscuousness, to the exclusion of one of its lawful occupants. The dispute ran high; but it must be added to the already numerous proofs of the superior energy proceeding from aroused maternal feelings, that the intruder was maintained in his usurped resting-place by his determined parent, notwithstanding the discontent naturally caused by such a proceeding.

We have now reached the centre of these provinces, the destinies of which have offered to Europe so singular an example of political vicissitude. It is an attractive occupation, in studying the history of this country, to watch the progress of the state, the ancient capital of which we have just visited,—a province which, from being probably the rudest and poorest of the whole Peninsula, became the most influential, the wealthiest, the focus of power, as it is geographically the centre of Spain,—and to witness its constantly progressive advance, as it gradually drew within the range of its influence all the surrounding states; exemplifying the dogged perseverance of the Spanish character, which, notwithstanding repeated defeat, undermined the Arab power by imperceptible advances, and eventually ridded the Peninsula of its long-established lords. It is interesting to thread the intricate narrative of intermarriages, treaties, wars, alliances, and successions, interspersed with deeds of heroic chivalry and of blackest treachery, composing the annals of the different northern states of Spain; until at length, the Christian domination having been borne onward by successive advantages nearly to the extreme southern shores of the Peninsula, a marriage unites the two principal kingdoms, and leads to the subjection of all Spain, as at present, under one monarch.