полная версия

полная версияThe Picturesque Antiquities of Spain

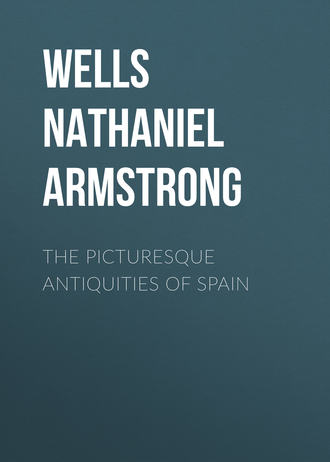

FAÇADE OF THE ALCAZAR, SEVILLE.

Having passed through the first entrance, you are in a large square, surrounded with buildings without ornament, and used at present as government offices. At the opposite side another archway passes under the buildings, and leads to a second large court. This communicates on the left with one or two others; one of these is rather ornamental, and in the Italian style, surrounded by an arcade supported on double columns, and enclosing a garden sunk considerably below the level of the ground. This court is approached by a covered passage, leading, as already mentioned, from the left side of the second large square, the south side of which—the side opposite to that on which we entered—consists of the façade and portal of the inner palace of all;—the Arab ornamental portion, the residence of the royal person.

At the right-hand extremity of this front is the entrance to the first floor, approached by a staircase, which occupies part of the building on that side of the square, and which contains the apartments of the governor. The staircase is open to the air, and is visible through a light arcade. The centre portal of this façade is ornamented, from the ground to the roof, with rich tracery, varied by a band of blue and white azulejos, and terminating in an advancing roof of carved cedar. Right and left, the rest of the front consists of a plain wall up to the first floor, on which small arcades, of a graceful design, enclose retreating balconies and windows.

Entering through the centre door, a magnificent apartment has been annihilated by two white partitions, rising from the ground to the ceiling, and dividing it into three portions, the centre one forming the passage which leads from the entrance to the principal court. Several of the apartments are thus injured, owing to the palace being occasionally used as a temporary lodging for the court. Passing across the degraded hall, a magnificent embroidered arch—for the carving with which it is covered more resembles embroidery than any other ornament—gives access to the great court.

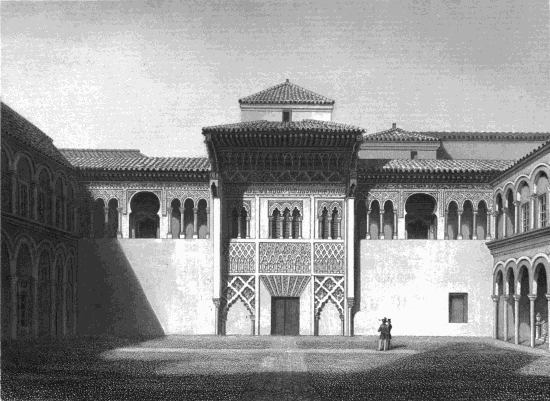

It is difficult to ascertain what portion of this palace belongs to the residence of the Moorish Kings, as Pedro the Cruel had a considerable portion of it rebuilt by Moorish architects in the same style. The still more recent additions are easily distinguished. One of them, in this part of the edifice, is a gallery, erected by Charles the Fifth, over the arcades of the great court. This gallery one would imagine to have been there placed with a view to demonstrate the superiority of Arab art over every other. It is conceived in the most elegant Italian style, and executed in white marble; but, compared with the fairy arcades which support it, it is clumsiness itself. The court is paved with white marble slabs, and contains in the centre a small basin of the same material, of chaste and simple form, once a fountain. The arcades are supported on pairs of columns, measuring about twelve diameters in height, and of equal diameter throughout. The capitals are in imitation of the Corinthian. The entire walls, over and round the arches, are covered with deep tracery in stucco; the design of which consists of diamond-shaped compartments, formed by lines descending from the cornice, and intersecting each other diagonally. These are indented in small curves, four to each side of the diamond. In each centre is a shell, surrounded by fanciful ornaments. The same design is repeated on the inside of the walls, that is, under the arcade, but only on the outer wall; and this portion of the court is covered with a richly-ornamented ceiling of Alerce, in the manner called artesonado.

On the opposite side of the court to that on which we entered, another semicircular arch, of equal richness, leads to a room extending the whole length of the court, and similar in form to that situated at the entrance, possessing also an ornamental ceiling, but plainer walls. The left and right sides of the court are shorter than the others. In the centre of the left side, a deep alcove is formed in the wall, probably occupied in former times by a sofa or throne: at present it is empty, with the exception, in one corner, of a dusty collection of azulejos fallen from the walls, and exposing to temptation the itching palms of enthusiasts. At the opposite end a large arch, admirably carved, and containing some superb old cedar doors, leads to the Hall of Ambassadors. This apartment is a square of about thirty-three feet, by nearly sixty in height. It is also called the media naranja (half-orange), from the form of its ceiling.

GREAT COURT OF THE ALCAZAR, SEVILLE.

In the centre of each side is an entrance, that from the court consists of the arch just mentioned, forming a semicircle with the extremities prolonged in a parallel direction. Those of the three other sides are each composed of three arches of the horse-shoe form, or three-quarters of a circle, and supported by two columns of rare marbles and jasper surmounted by gilded capitals. The walls are entirely covered with elegant designs, executed in stucco, the effect of which suffers from a series of small arches, running round the upper part of the room, having been deprived of their tracery to make room for the painted heads (more or less resembling) of the kings of Spain, Goths and their successors, excepting the Arabs and Moors. This degradation is, however, forgotten from the moment the eye is directed to the ceiling.

In the Arab architecture, the ornament usually becomes more choice, as it occupies a higher elevation; and the richest and most exquisite labours of the artist are lavished on the ceilings. The designs are complicated geometrical problems, by means of which the decorators of that nation of mathematicians and artists attained to a perfection of ornament unapproached by any other style. From the cornice of this room rise clusters of diminutive gilded semi-cupolas, commencing by a single one, upon which two are supported, and multiplying so rapidly as they rise, some advancing, others retreating, and each resting on a shoulder of one below, that, by the time they reach the edge of the great cupola, they appear to be countless. The ornament of this dome consists of innumerable gilt projecting bands, of about two inches in width; these intersect each other in an infinite profusion of curves, as they stretch over the hemispherical space. The artist, who would make a pencil sketch of this ceiling, should be as deep a geometrician as the architect who designed it.

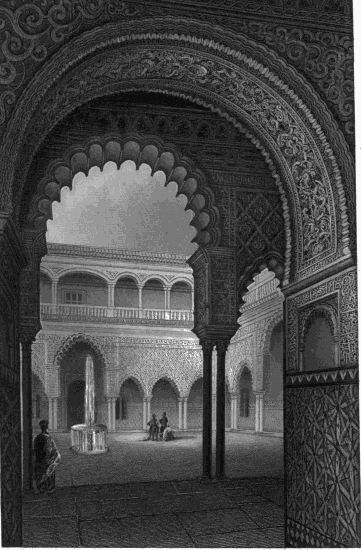

On quitting the Hall of Ambassadors, we arrive at the best part of the building. Passing through the arcade at the right-hand side, a long narrow apartment is crossed, which opens on a small court called the Court of Dolls (Patio de los Muceñas). No description, no painting can do justice to this exquisite little enclosure. You stand still, gazing round until your delight changes into astonishment at such an effect being produced by immoveable walls and a few columns. A space, of about twenty feet by thirty,—in which ten small pillars, placed at corresponding but unequal distances, enclose a smaller quadrangle, and support, over a series of different sized arches, the upper walls,—has furnished materials to the artist for the attainment of one of the most successful results in architecture. The Alhambra has nothing equal to it. Its two large courts surpass, no doubt, in beauty the principal court of this palace; but, as a whole, this residence, principally from its being in better preservation and containing more, is superior to that of Granada, always excepting the advantage derived from the picturesque site of the latter. The Court of Dolls, at all events, is unrivalled.

COURT OF DOLLS, ALCAZAR, SEVILLE. 10

The architect made here a highly judicious use of some of the best gleanings from Italica, consisting of a few antique capitals, which, being separated from their shafts, have been provided with others, neither made for them, nor even fitted to them. The pillars are small, and long for their diameter, with the exception of the four which occupy the angles, which are thicker and all white. The rest are of different coloured marbles, and all are about six feet in height. The capitals are of still smaller proportions; so that at the junction they do not cover the entire top of the shaft. This defect, from what cause it is difficult to explain, appears to add to their beauty.

The capitals are exquisitely beautiful. One in particular, apparently Greek, tinged by antiquity with a slight approach to rose colour, is shaped, as if carelessly, at the will of the sculptor; and derives from its irregularly rounded volutes and uneven leaves, an inconceivable grace. The arches are of various shapes, that is, of three different shapes and dimensions, and whether more care, or better materials were employed in the tracery of the walls in this court, or for whatever other reason, it is in better preservation than the other parts of the palace. It has the appearance of having been newly executed in hard white stone.

Through the Court of Dolls you pass into an inner apartment, to which it is a worthy introduction. This room has been selected in modern times, as being the best in the palace, for the experiment of restoring the ceiling. The operation has been judiciously executed, and produces an admirable effect. The design of this ceiling is the most tasteful of the whole collection. Six or seven stars placed at equal distances from each other, form centres, from which, following the direction of the sides of their acute angles, depart as many lines; that is, two from each point; or, supposing the star to have twelve points—twenty-four from each star: but these lines soon change their directions, and intersecting each other repeatedly, form innumerable small inclosures of an hexagonal shape. The lines are gilt. Each hexagonal compartment rises in relief of about an inch and a half from the surface, and is ornamented with a flower, painted in brilliant colours on a dark ground.

The room is twenty-four feet in height by only sixteen wide, and between sixty and seventy in length. At the two ends, square spaces are separated from the centre portion by a wall, advancing about two feet from each side, and supporting an arch, extending across the entire width. These arches were probably furnished with curtains, which separated at will the two ends from the principal apartment, and converted them into sleeping retreats. Their ornaments are still more choice than those of the centre. With the exception of this room, all the principal apartments, and the two courts, are decorated from the ground upwards to a height of about five feet, with the azulejos, or mosaic of porcelain tiles, the colours of which never lose their brilliancy.

The first floor is probably an addition made entirely subsequently to the time of the Moors. It contains several suites of plain white-washed rooms, and only two ornamental apartments, probably of Don Pedro's time. These are equal to those on the ground floor with respect to the tracery of the walls, unfortunately almost filled with white-wash; but their ceilings are plainer. There is a gallery over the Court of Dolls, of a different sort from the rest, but scarcely inferior in beauty to any part of the edifice. The pillars, balustrades, and ceilings, are of wood.

One of the last mentioned apartments has an advantage over all the rest of the palace, derived from its position. It opens on a terrace looking over the antique gardens,—a view the most charming and original that can be imagined. This room must be supposed to have been the boudoir of Maria Padilla,—the object of the earliest and most durable of Pedro's attachments; whose power over him outlived the influence of all his future liaisons. It is indeed probable that the taste for this residence, and the creation of a large portion of its beauties, are to be attributed to the mistress, rather than to a gloomy and bloodthirsty king, as Pedro is represented to have been, and whose existence was totally unsuited to such a residence. In the Court of Dolls the portion of pavement is pointed out on which his brother Don Fadrique fell, slaughtered, as some say, by Pedro's own hand,—at all events in his presence, and by his order.

This monarch, were his palace not sufficient to immortalize him, would have a claim to immortality, as having ordered more executions than all the other monarchs who ever ruled in Spain, added together. It appears to have been a daily necessity for him; but he derived more than ordinary satisfaction when an opportunity could be obtained of ordering an archbishop to the block. The see of Toledo became under him the most perilous post in the kingdom, next to that of his own relatives: but he occasionally extended the privilege to other archbishopricks. It is a relief to meet with a case of almost merited murder in so sanguinary a list. Such may be termed the adventure of an innocent man, who, seeing before him a noose which closes upon everything which approaches it, carefully inserts his neck within the circumference.

This was the case of a monk, who, hearing that Pedro, during one of his campaigns, was encamped in a neighbouring village, proceeded thither, and demanded an audience. His request being immediately granted, no doubt in the expectation of some valuable information respecting the enemy's movements, the holy man commenced an edifying discourse, in which he informed Don Pedro, that the venerabilissimo San Somebody (the saint of his village) had passed a considerable time with him in his dream of the previous night: that his object in thus miraculously waiting upon him was, to request he would go to his Majesty, and tell him, that, owing to the unpardonable disorders of his life, it was determined he should lose the approaching battle. It was the unhappy friar's last sermon; for in less than five minutes he had ceased to exist.

It stands to reason, that, owing to the retired habits of this friar, a certain anecdote had never reached his ear relative to another member of a religious fraternity. At a period that had not long preceded the event just related, the misconduct of this sovereign had drawn down upon him the displeasure of the head of the church.11 The thunderbolt was already forged beneath the arches of the Vatican; but a serious difficulty presented itself. The culprit was likely to turn upon the hand employed in inflicting the chastisement. At length a young monk, known to a member of the holy synod as a genius of promise, energetic and fertile in resources, was made choice of, who unhesitatingly undertook the mission. He repaired to Seville, and after a few days' delay, employed in combining his plan of operation, he got into a boat, furnished with two stout rowers, and allowing the current to waft him down the Guadalquivir, until he arrived opposite a portion of the bank known to be the daily resort of the King, he approached the shore, and waited his opportunity.

At the accustomed hour the royal cavalcade was seen to approach; when, standing up in the boat, which was not allowed to touch the shore, he made signs that he would speak to the party. The monkish costume commanded respect even from royalty, and Don Pedro reined in his horse. The monk then inquired whether it would gratify his Majesty to listen to the news of certain remarkable occurrences that had taken place in the East, from which part of the world he had just arrived. The King approached, and ordered him to tell his story: upon which he unrolled the fatal document, and with all possible rapidity of enunciation read it from beginning to end.

Before it was concluded, the King had drawn his sword, and spurred his horse to the brink of the water; but at his first movement the boat had pushed off,—the reader still continuing his task,—so that by the time Pedro found himself completely excommunicated, his rage passing all bounds, he had dashed into the water, directing a sabre cut, which only reached the boat's stern. He still, however, spurred furiously on, and compelled his horse to swim a considerable distance; until, the animal becoming exhausted, he only regained the shore after being in serious danger of drowning. It may easily be imagined that the papal messenger, satisfied with his success, avoided the contact of terra firma, until he found himself clear of Pedro's dominions.

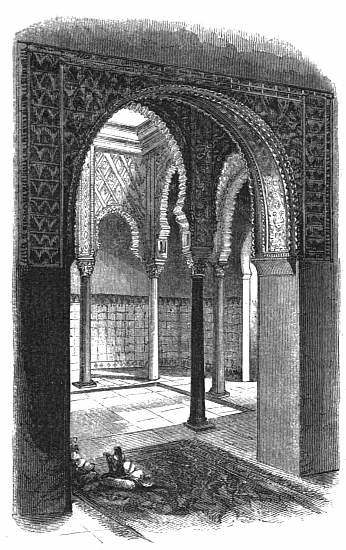

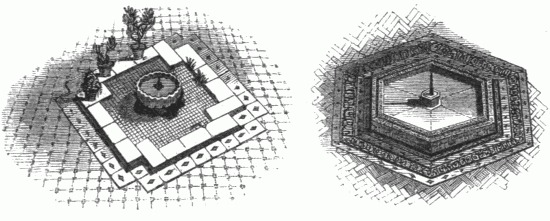

Quitting the room—that of Maria Padilla (according to my conjecture) by the door which leads to the terrace, you look down on a square portion of ground, partitioned off from the rest by walls, against which orange-trees are trained like our wall-fruit trees, only so thickly that no part of the masonry is visible. All the walls in the garden are thus masked by a depth of about eight inches of leaves evenly clipped. In the fruit season the effect is admirable. The small square portions next to the palace thus partitioned off are laid out in flower-beds, separated by walks of mixed brick and porcelain, all of which communicate with fountains in the centres. The fountains, simple and destitute of the usual classical menagerie of marine zoology and gods and goddesses, whose coöperation is so indispensable in most European gardens to the propulsion of each curling thread or gushing mass of the cold element,—derive all their charm from the purity and taste displayed in their design. One of the most beautiful of them consists merely of a raised step, covered with azulejos, enclosing a space of an hexagonal form, in the centre of which the water rises from a small block of corresponding form and materials. The mosaic is continued outside the step, but covers only a narrow space.

FOUNTAINS AT THE ALCAZAR.

The terrace stretches away to the left as far as the extremity of the buildings, the façade of which is hollowed out into a series of semicircular alcoves; there being no doors nor windows, with the exception of the door of the room through which we issued. The alcoves are surrounded with seats, and form so many little apartments, untenable during the summer, as they look to the south, but forming excellent winter habitations. Arrived at the extremity of the palace front, the promenade may be continued at the same elevation down another whole side of the gardens, along a terrace of two stories, which follows the outer enclosure. This terrace is very ornamental. From the ground up to a third of its height, its front is clothed with the orange-tree, in the same manner as the walls already described. Immediately above runs a rustic story of large projecting stones, which serves as a basement for the covered gallery, or lower of the two walks. This gallery is closed on the outside, which is part of the town wall. The front or garden side is composed of a series of rustic arches, alternately larger and smaller, formed of rugged stones, such as are used for grottoes, and of a dark brown colour—partly natural, partly painted.

The arches are supported by marble columns, or rather fragments of columns,—all the mutilated antique trunks rummaged out of Italica. For a shaft of insufficient length a piece is found of the dimensions required to make up the deficiency, and placed on its top without mortar or cement. Some of the capitals are extremely curious. Among them almost every style may be traced, from the Hindoo to the Composite: but no one is entire, nor matched with any part of the column it was originally destined to adorn. Over this gallery is the open terrace, which continues that of the palace side on the same level. The view extends in all directions, including the gardens and the surrounding country; for we are here at the extremity of the town. At the furthest end the edifice widens, and forms an open saloon, surrounded with seats, glittering with the bright hues of the azulejos.

From these terraces you look down on the portion of the garden in which the royal arms are represented, formed with myrtle-hedges. Eagles, lions, castellated towers,—all are accurately delineated. Myrtle-hedges are also used in all parts of the gardens as borders to the walks. It is a charming evening's occupation to wander through the different enclosures of these gardens, which, although not very extensive, are characterised by so much that is uncommon in their plan and ornaments, that the lounger is never weary of them. Nor is the visible portion of their attractions more curious than the hidden sources of amusement and—ablution, by means of which an uninitiated wanderer over these china-paved walks, may be unexpectedly, and more than necessarily refreshed. By means of a handle, concealed—here in the lungs of some bathing Diana in the recesses of her grotto—here in the hollow of a harmless looking stone—an entire line of walk is instantaneously converted into a stage of hydraulics—displaying to the spectator a long line of embroidery, composed of thousands of silver threads sparkling in the sunshine, as issuing from unseen apertures in the pavement they cross each other at a height of a few feet from the ground, forming an endless variety of graceful curves. Almost all the walks are sown with these burladores, as they are termed.

A large portion of the grounds consists of an orange-grove, varied with sweet lemon-trees. The trees are sufficiently near to each other to afford universal shade, without being so thickly planted as to interfere with the good-keeping of the grass, nor with the movement of promenading parties. In the centre of this grove is a beautiful edifice,—a square pavilion entirely faced, within and without, with the azulejos, with the exception only of the roof. Around it is a colonnade of white marble, enclosing a space raised two feet above the ground, and surrounded by a seat of the same mosaic. The interior is occupied by a table, surrounded with seats.

The subterranean baths, called the baths of Maria Padilla, are entered from the palace end of the garden. They extend to a considerable distance under the palace, and must during the summer heats, have been a delightfully cool retreat.

This alcazar is probably the best specimen of a Moorish residence remaining in Europe. The Alhambra would, no doubt, have surpassed it, but for the preference accorded by the Emperor, Charles the Fifth, to its situation over that of Seville: owing to which he contented himself with building a gallery over the principal court at the latter; while at Granada, he destroyed a large portion of the old buildings, which he replaced by an entire Italian palace. At present the ornamented apartments of the Seville palace are more numerous, and in better preservation than those of the Alhambra.

Both, however, would have been thrown into the shade, had any proportionate traces existed of the palace of Abderahman the Third, in the environs of Cordova. Unfortunately nothing of this remains but the description. It is among the few Arab manuscripts which escaped the colossal auto-da-fé of Ferdinand and Isabella, and would appear too extravagant to merit belief, but for the known minuteness and accuracy of the Arab writers, proved by their descriptions of the palaces and other edifices which remain to afford the test of comparison.

The immense wealth lavished by these princes, must also be taken into consideration, and especially by the Caliphs of Cordova, who possessed a far more extended sway than belonged to the subsequent dynasties of Seville and Granada. According to a custom prevalent at their court, rich presents were offered to the sovereign on various occasions. Among others, governors of provinces, on their nomination, seldom neglected this practical demonstration of gratitude. This practice is to this day observed at the court of the Turkish Sultan, and serves to swell the treasury in no small degree. Abderahman the Third, having granted a government to the brother of his favourite, Ahmed ben Sayd, the two brothers joined purses, and offered a present made up of the following articles—accompanied by delicate and ingenious compliments in verse, for the composition of which they employed the most popular poet of the day:—Four hundred pounds weight of pure gold; forty thousand sequins in ingots of silver; four hundred pounds of aloes; five hundred ounces of amber; three hundred ounces of camphor; thirty pieces of tissue of gold and silk; a hundred and ten fine furs of Khorasan; forty-eight caparisons of gold and silk, woven at Bagdad; four thousand pounds of silk in balls; thirty Persian carpets; eight hundred suits of armour; a thousand shields; a hundred thousand arrows; fifteen Arabian, and a hundred Spanish horses, with their trappings and equipments; sixty young slaves—forty male, and twenty female.