полная версия

полная версияIsland Life; Or, The Phenomena and Causes of Insular Faunas and Floras

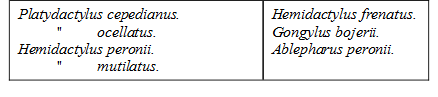

Four species of chameleon are now recorded from Bourbon and one from Mauritius (J. Reay Greene, M.D., in Pop. Science Rev. April, 1880), but as they are not mentioned by the old writers, it is pretty certain that these creatures are recent introductions, and this is the more probable as they are favourite domestic pets.

Darwin informed me that in a work entitled Voyage à l'Isle de France, par un Officier du Roi, published in 1770, it is stated that a fresh-water fish had been introduced from Batavia and had multiplied. The writer also says (p. 170): "On a essayé, mais sans succcès, d'y transporter des grenouilles qui mangent les œufs que les moustigues deposent sur les eaux stagnantes." It thus appears that there were then no frogs on the island.

162

That the dodo is really an abortion from a more perfect type, and not a direct development from some lower form of wingless bird, is shown by its possessing a keeled sternum, though the keel is exceedingly reduced, being only three-quarters of an inch deep in a length of seven inches. The most terrestrial pigeon—the Didunculus of the Samoan Islands, has a far deeper and better developed keel, showing that in the case of the dodo the degradation has been extreme. We have also analogous examples in other extinct birds of the same group of islands, such as the flightless Rails—Aphanapteryx of Mauritius and Erythromachus of Rodriguez, as well as the large parrot—Lophopsittacus of Mauritius, and the Night Heron, Nycticorax megacephala of Rodriguez, the last two birds probably having been able to fly a little. The commencement of the same process is to be seen in the peculiar dove of the Seychelles, Turtur rostratus, which, as Mr. Edward Newton has shown, has much shorter wings than its close ally, T. picturatus, of Madagascar. For a full and interesting account of these and other recently extinct birds see Professor Newton's article on "Fossil Birds" in the Encyclopædia Britannica, ninth edition, vol. iii., p. 732; and that on "The Extinct Birds of Rodriguez," by Dr. A. Günther and Mr. E. Newton, in the Royal Society's volume on the Transit of Venus Expedition.

163

See Ibis, 1877, p. 334.

164

A common Indian and Malayan toad (Bufo melanostictus) has been introduced into Mauritius and also some European toads, as I am informed by Dr. Günther.

165

This brief account of the Madagascar flora has been taken from a very interesting paper by the Rev. Richard Baron, F.L.S., F.G.S., in the Journal of the Linnean Society, Vol. XXV., p. 246; where much information is given on the distribution of the flora within the island.

166

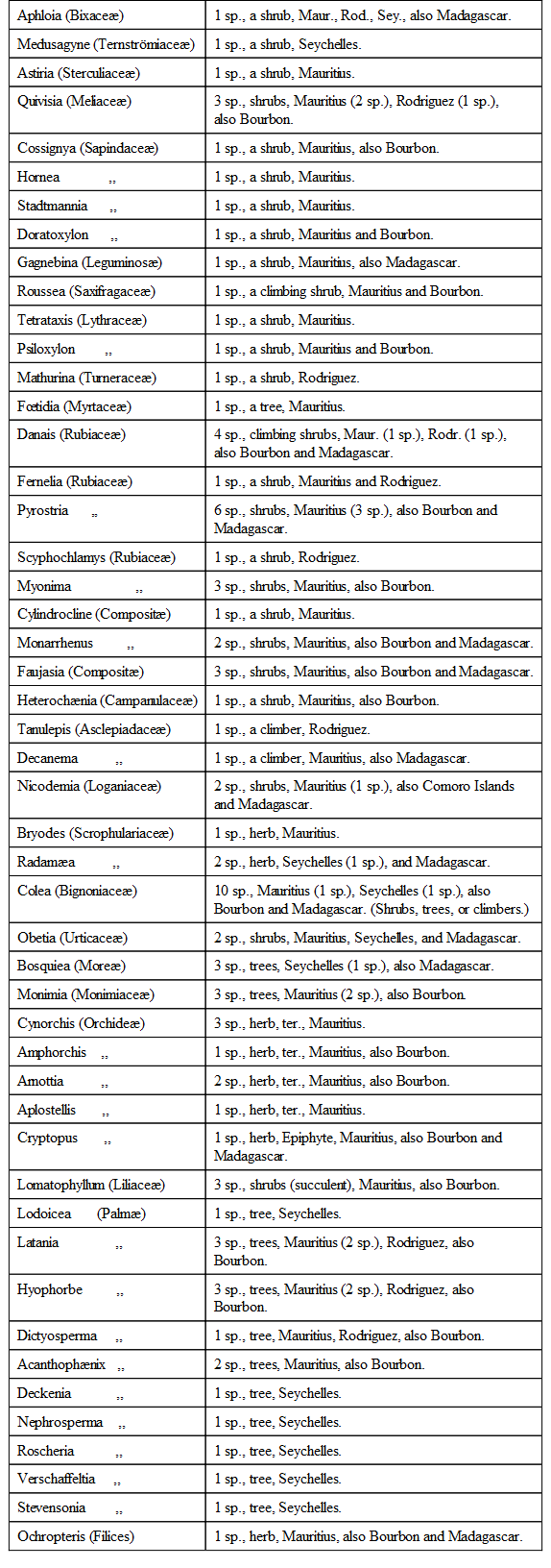

It may be interesting to botanists and to students of geographical distribution to give here an enumeration of the endemic genera of the Flora of the Mauritius and the Seychelles, as they are nowhere separately tabulated in that work.

Among the curious features in this list are the great number of endemic shrubs in Mauritius, and the remarkable assemblage of five endemic genera of palms in the Seychelles Islands. We may also notice that one palm (Latania loddigesii) is confined to Round Island and two other adjacent islets offering a singular analogy to the peculiar snake also found there.

167

168

For outline figures of the chief types of these butterflies, see my Malay Archipelago, Vol. I. p. 441, or p. 216 of the tenth edition.

169

Dobson on the Classification of Chiroptera (Ann. and Mag. of Nat. Hist. Nov. 1875).

170

See Buller, "On the New Zealand Rat," Trans. of the N. Z. Institute (1870), Vol. III. p. 1, and Vol. IX. p. 348; and Hutton, "On the Geographical Relations of the New Zealand Fauna," Trans. N. Z. Instit. 1872, p. 229.

171

Hochstetter's New Zealand, p. 161, note.

172

The animal described by Captain Cook as having been seen at Pickersgill Harbour in Dusky Bay (Cook's 2nd Voyage, Vol. I. p. 98) may have been the same creature. He says, "A four-footed animal was seen by three or four of our people, but as no two gave the same description of it, I cannot say what kind it is. All, however, agreed that it was about the size of a cat, with short legs, and of a mouse colour. One of the seamen, and he who had the best view of it, said it had a bushy tail, and was the most like a jackal of any animal he knew." It is suggestive that, so far as the points on which "all agreed"—the size and the dark colour—this description would answer well to the animal so recently seen, while the "short legs" correspond to the otter-like tracks, and the thick tail of an otter-like animal may well have appeared "bushy" when the fur was dry. It has been suggested that it was only one of the native dogs; but as none of those who saw it took it for a dog, and the points on which they all agreed are not dog-like, we can hardly accept this explanation; while the actual existence of an unknown animal in New Zealand of corresponding size and colour is confirmed by this account of a similar animal having been seen about a century ago.

173

Owen, "On the Genus Dinornis," Trans. Zool. Soc. Vol. X. p. 184. Mivart, "On the Axial Skeleton of the Struthionidæ," Trans. Zool. Soc. Vol. X. p. 51.

174

The recent existence of the Moa and its having been exterminated by the Maoris appears to be at length set at rest by the statement of Mr. John White, a gentleman who has been collecting materials for a history of the natives for thirty-five years, who has been initiated by their priests into all their mysteries, and is said to "know more about the history, habits, and customs of the Maoris than they do themselves." His information on this subject was obtained from old natives long before the controversy on the subject arose. He says that the histories and songs of the Maoris abound in allusions to the Moa, and that they were able to give full accounts of "its habits, food, the season of the year it was killed, its appearance, strength, and all the numerous ceremonies which were enacted by the natives before they began the hunt, the mode of hunting, how cut up, how cooked, and what wood was used in the cooking, with an account of its nest, and how the nest was made, where it usually lived, &c." Two pages are occupied by these details, but they are only given from memory, and Mr. White promises a full account from his MSS. Many of the details given correspond with facts ascertained from the discovery of native cooking places with Moas' bones; and it seems quite incredible that such an elaborate and detailed account should be all invention. (See Transactions of the New Zealand Institute, Vol. VIII. p. 79.)

175

See fig. in Trans. of N. Z. Institute, Vol. III., plate 12b. fig. 2.

176

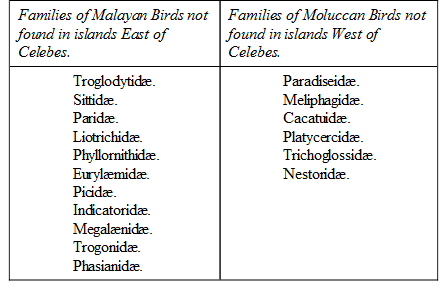

Geographical Distribution of Animals, Vol. I., p. 450.

177

In my Geographical Distribution of Animals (I. p. 541) I have given two peculiar Australian genera (Orthonyx and Tribonyx) as occurring in New Zealand. But the former has been found in New Guinea, while the New Zealand bird is considered to form a distinct genus, Clitonyx; and the latter inhabits Tasmania, and was recorded from New Zealand through an error. (See Ibis, 1873, p. 427.)

178

The peculiar genera of Australian lizards according to Boulenger's British Museum Catalogue, are as follows:—Family Geckonidæ: Nephrurus, Rhynchœdura, Heteronota, Diplodactylus, Œdura. Family Pygopodidæ (peculiar): Pygopus, Cryptodelma, Delma, Pletholax, Aprasia. Family Agamidæ: Chelosania, Amphibolurus, Tympanocryptis, Diporophora, Chlamydosaurus, Moloch, Oreodeira. Family Scincidæ: Egerina, Trachysaurus, Hemisphænodon. Family doubtful: Ophiopsiseps.

179

These figures are taken from Mr. G. M. Thomson's address "On the Origin of the New Zealand Flora," Trans. N. Z. Institute, XIV. (1881), being the latest that I can obtain. They differ somewhat from those given in the first edition, but not so as to affect the conclusions drawn from them.

180

This accords with the general scarcity of Leguminosæ in Oceanic Islands, due probably to their usually dry and heavy seeds, not adapted to any of the forms of aërial transmission; and it would indicate either that New Zealand was never absolutely united with Australia, or that the union was at a very remote period when Leguminosæ were either not differentiated or comparatively rare.

181

Sir Joseph Hooker informs me that the number of tropical Australian plants discovered within the last twenty years is very great, and that the statement as above made may have to be modified. Looking, however, at the enormous disproportion of the figures given in the "Introductory Essay" in 1859 (2,200 tropical to 5,800 temperate species) it seems hardly possible that a great difference should not still exist, at all events as regards species. In Baron von Müeller's latest summary of the Australian Flora (Second Systematic Census of Australian Plants, 1889), he gives the total species at 8,839, of which 3,560 occur in West Australia, and 3,251 in New South Wales. On counting the species common to these two colonies in fifty pages of the Census taken at random, I find them to be about one-tenth of the total species in both. This would give the number of distinct species in these areas as about 6,130. Adding to these the species peculiar to Victoria and South Australia, we shall have a flora of near 6,500 in the temperate parts of Australia. It is true that West Australia extends far into the tropics, but an overwhelming majority of the species have been discovered in the south-western portion of the colony, while the species that may be exclusively tropical will be more than balanced by those of temperate Queensland, which have not been taken account of, as that colony is half temperate and half tropical. It thus appears probable that full three fourths of the species of Australian plants occur in the temperate regions, and are mainly characteristic of it. Sir Joseph Hooker also doubts the generally greater richness of tropical over temperate floras which I have taken as almost an axiom. He says: "Taking similar areas to Australia in the Western World, e.g., tropical Africa north of 20° S. Lat. as against temperate Africa and Europe up to 47°—I suspect that the latter would present more genera and species than the former." This, however, appears to me to be hardly a case in point, because Europe is a distinct continent from Africa and has had a very different past history, and it is not a fair comparison to take the tropical area in one continent while the temperate is made up of widely separated areas in two continents. A closer parallel may perhaps be found in equal areas of Brazil and south temperate America, or of Mexico and the Southern United States, in both of which cases I suppose there can be little doubt that the tropical areas are far the richest. Temperate South Africa is, no doubt, always quoted as richer than an equal area of tropical Africa or perhaps than any part of the world of equal extent, but this is admitted to be an exceptional case.

182

Sir Joseph Hooker thinks that later discoveries in the Australian Alps and other parts of East and South Australia may have greatly modified or perhaps reversed the above estimate, and the figures given in the preceding note indicate that this is so. But still, the small area of South-west Australia will be, proportionally, far the richer of the two. It is much to be desired that the enormous mass of facts contained in Mr. Bentham's Flora Australiensis and Baron von Müeller's Census should be tabulated and compared by some competent botanist, so as to exhibit the various relations of its wonderful vegetation in the same manner as was done by Sir Joseph Hooker with the materials available twenty-one years ago.

183

From an examination of the fossil corals of the South-west of Victoria, Professor P. M. Duncan concludes—"that, at the time of the formation of these deposits the central area of Australia was occupied by sea, having open water to the north, with reefs in the neighbourhood of Java." The age of these fossils is not known, but as almost all are extinct species, and some are almost identical with European Pliocene and Miocene species, they are supposed to belong to a corresponding period. (Journal of Geol. Soc., 1870.)

184

"On the Origin of the Fauna and Flora of New Zealand," by Captain F. W. Hutton, in Annals and Mag. of Nat. Hist. Fifth series, p. 427 (June, 1884).

185

To these must now be added the genera Sequoia, Myrica, Aralia, and Acer, described by Baron von Ettingshausen. (Trans. N.Z. Institute, xix., p. 449.)

186

The large collection of fossil plants from the Tertiary beds of New Zealand which have been recently described by Baron von Ettingshausen (Trans. N. Z. Inst., vol. xxiii., pp. 237-310), prove that a change in the vegetation has occurred similar to that which has taken place in Eastern Australia, and that the plants of the two countries once resembled each other more than they do now. We have, first, a series of groups now living in Australia, but which have become extinct in New Zealand, as Cassia, Dalbergia, Eucalyptus, Diospyros, Dryandra, Casuarina, and Ficus; and also such northern genera as Acer, Planera, Ulmus, Quercus, Alnus, Myrica, and Sequoia. All these latter, except Ulmus and Planera, have been found also in the Eastern-Australian Tertiaries, and we may therefore consider that at this period the northern temperate element in both floras was identical. If this flora entered both countries from the south, and was really Antarctic, its extinction in New Zealand may have been due to the submergence of the country to the south, and its elevation and extension towards the tropics, admitting of the incursion of the large number of Polynesian and tropical Australian types now found there; while the Australian portion of the same flora may have succumbed at a somewhat later period, when the elevation of the Cretaceous and Tertiary sea united it with Western Australia, and allowed the rich typical Australian flora to overrun the country. Of course we are assuming that the identification of these genera is for the most part correct, though almost entirely founded on leaves only. Fuller knowledge, both of the extinct flora itself and of the geological age of the several deposits, is requisite before any trustworthy explanation of the phenomena can be arrived at.

187

The following are the tropical genera common to New Zealand and Australia:—

1. Melicope. Queensland, Pacific Islands.

2. Eugenia. Eastern and Tropical Australia, Asia, and America.

3. Passiflora. N.S.W. and Queensland, Tropics of Old World and America.

4. Myrsine. Tropical and Temperate Australia, Tropical and Sub-tropical regions.

5. Sapota. Australia, Norfolk Islands, Tropics.

6. Cyathodes. Australia and Pacific Islands.

7. Parsonsia. Tropical Australia and Asia.

8. Geniostoma. Queensland, Polynesia, Asia.

9. Mitrasacme. Tropical and Temperate Australia, India.

10. Ipomœa. Tropical Australia, Tropics.

11. Mazus. Temperate Australia, India, China.

12. Vitex. Tropical Australia, Tropical and Sub-tropical.

13. Pisonia. Tropical Australia, Tropical and Sub-tropical.

14. Alternanthera. Tropical Australia, India, and S. America.

15. Tetranthera. Tropical Australia, Tropics.

16. Santalum. Tropical and Sub-tropical Australia, Pacific, Malay Islands.

17. Carumbium. Tropical and Sub-tropical Australia, Pacific Islands.

18. Elatostemma. Sub-tropical Australia, Asia, Pacific Islands.

19. Peperomia. Tropical and Sub-tropical Australia, Tropics.

20. Piper. Tropical and Sub-tropical Australia, Tropics.

21. Dacrydium. Tasmania, Malay, and Pacific Islands.

22. Dammara. Tropical Australia, Malay, and Pacific Islands.

23. Dendrobium. Tropical Australia, Eastern Tropics.

24. Bolbophyllum. Tropical and Sub-tropical Australia, Tropics.

25. Sarcochilus. Tropical and Sub-tropical Australia, Fiji, and Malay Islands.

26. Freycinetia. Tropical Australia, Tropical Asia.

27. Cordyline. Tropical Australia, Pacific Islands.

28. Dianella. Australia, India, Madagascar, Pacific Islands.

29. Cyperus. Australia, Tropical regions mainly.

30. Fimbristylis. Tropical Australia, Tropical regions.

31. Paspalum. Tropical and Sub-tropical grasses.

32. Isachne. Tropical and Sub-tropical grasses.

33. Sporobolus. Tropical and Sub-tropical grasses.

188

Insects are tolerably abundant in the open mountain regions, but very scarce in the forests. Mr. Meyrick says that these are "strangely deficient in insects, the same species occurring throughout the islands;" and Mr. Pascoe remarked that "the forests of New Zealand were the most barren country, entomologically, he had ever visited." (Proc. Ent. Soc., 1883. p. xxix.)

189

Introductory Essay On the Flora of Australia, p. 130.

190

Hooker, On the Flora of Australia, p. 95.—H. C. Watson, in Godman's Azores, pp. 278-286.

191

As this is a point of great interest in its bearing on the dispersal of plants by means of mountain ranges, I have endeavoured to obtain a few illustrative facts:—

1. Mr. William Mitten, of Hurstpierpoint, Sussex, informs me that when the London and Brighton railway was in progress in his neighbourhood, Melilotus vulgaris made its appearance on the banks, remained for several years, and then altogether disappeared. Another case is that of Diplotaxis muralis, which formerly occurred only near the sea-coast of Sussex, and at Lewes; but since the railway was made has spread along it, and still maintains itself abundantly on the railway banks though rarely found anywhere else.

2. A correspondent in Tasmania informs me that whenever the virgin forest is cleared in that island there invariably comes up a thick crop of a plant locally known as fire-weed—a species of Senecio, probably S. Australis. It never grows except where the fire has gone over the ground, and is unknown except in such places. My correspondent adds:—"This autumn I went back about thirty-five miles through a dense forest, along a track marked by some prospectors the year before, and in one spot where they had camped, and the fire had burnt the fallen logs, &c., there was a fine crop of 'fire-weed.' All around for many miles was a forest of the largest trees and dense scrub." Here we have a case in which burnt soil and ashes favour the germination of a particular plant, whose seeds are easily carried by the wind, and it is not difficult to see how this peculiarity might favour the dispersal of the species for enormous distances, by enabling it temporarily to grow and produce seeds on burnt spots.

3. In answer to an inquiry on this subject, Mr. H. C. Watson has been kind enough to send me a detailed account of the progress of vegetation on the railway banks and cuttings about Thames Ditton. This account is written from memory, but as Mr. Watson states that he took a great interest in watching the process year by year, there can be no reason to doubt the accuracy of his memory. I give a few extracts which bear especially on the subject we are discussing.

"One rather remarkable biennial plant appeared early (the second year, as I recollect) and renewed itself either two or three years, namely, Isatis tinctoria—a species usually supposed, to be one of our introduced, but pretty well naturalised, plants. The nearest stations then or since known to me for this Isatis are on chalk about Guildford, twenty miles distant. There were two or three plants of it at first, never more than half a dozen. Once since I saw a plant of Isatis on the railway bank near Vauxhall.

"Close by Ditton Station three species appeared which may be called interlopers. The biennial Barbarea precox, one of these, is the least remarkable, because it might have come as seed in the earth from some garden, or possibly in the Thames gravel (used as ballast). At first it increased to several plants, then became less numerous, and will soon, in all probability, become extinct, crowded out by other plants. The biennial Petroselinum segetum was at first one very luxuriant plant on the slope of the embankment. It increased by seed into a dozen or a score, and is now nearly if not quite extinct. The third species is Linaria purpurea, not strictly a British plant, but one established in some places on old walls. A single root of it appeared on the chalk facing of the embankment by Ditton Station. It has remained there several years and grown into a vigorous specimen. Two or three smaller examples are now seen by it, doubtless sprung from some of the hundreds or thousands of seeds shed by the original one plant. The species is not included in Salmon and Brewer's Flora of Surrey.

"The main line of the railway has introduced into Ditton parish the perennial Arabis hirsuta, likely to become a permanent inhabitant. The species is found on the chalk and greensand miles away from Thames Ditton; but neither in this parish nor in any adjacent parish, so far as known to myself or to the authors of the flora of the county, does it occur. Some years after the railway was made a single root of this Arabis was observed in the brickwork of an arch by which the railway is carried over a public road. A year or two afterwards there were three or four plants. In some later year I laid some of the ripened seed-pods between the bricks in places where the mortar had partly crumbled out. Now there are several scores of specimens in the brickwork of the arch. It is presumable that the first seed may have been brought from Guildford. But how could it get on to the perpendicular face of the brickwork?

"The Bee Orchis (Ophrys apifera), plentiful on some of the chalk lands in Surrey, is not a species of Thames Ditton, or (as I presume) of any adjacent parish. Thus, I was greatly surprised some years back to see about a hundred examples of it in flower in one clayey field either on the outskirts of Thames Ditton or just within the limits of the adjoining parish of Cobham. I had crossed this same field in a former year without observing the Ophrys there. And on finding it in the one field I closely searched the surrounding fields and copses, without finding it anywhere else. Gradually the plants became fewer and fewer in that one field, and some six or eight years after its first discovery there the species had quite disappeared again. I guessed it had been introduced with chalk, but could obtain no evidence to show this."

4. Mr. A. Bennett, of Croydon, has kindly furnished me with some information on the temporary vegetation of the banks and cuttings on the railway from Yarmouth to Caistor in Norfolk, where it passes over extensive sandy Denes with a sparse vegetation. The first year after the railway was made the banks produced abundance of Œnothera odorata and Delphinium Ajacis (the latter only known thirty miles off in cornfields in Cambridgeshire), with Atriplex patula and A. deltoidea. Gradually the native sand plants—Carices, Grasses, Galium verum, &c., established themselves, and year by year covered more ground till the new introductions almost completely disappeared. The same phenomenon was observed in Cambridgeshire between Chesterton and Newmarket, where, the soil being different, Stellaria media and other annuals appeared in large patches; but these soon gave way to a permanent vegetation of grasses, composites, &c., so that in the third year no Stellaria was to be seen.