полная версия

полная версияIsland Life; Or, The Phenomena and Causes of Insular Faunas and Floras

106

Nature, Vol. VI. p. 262, "Recent Observations in the Bermudas," by Mr. J. Matthew Jones.

107

"The late Sir C. Wyville Thomson was of opinion that the 'red earth' which largely forms the soil of Bermuda had an organic origin, as well as the 'red clay' which the Challenger discovered in all the greater depths of the ocean basins. He regarded the red earth and red clay as an ash left behind after the gradual removal of the lime by water charged with carbonic acid. This ash he regarded as a constituent part of the shells of Foraminifera, skeletons of Corals, and Molluscs, [vide Voyage of the Challenger, Atlantic, Vol. I. p. 316]. This theory does not seem to be in any way tenable. Analysis of carefully selected shells of Foraminifera, Heteropods, and Pteropods, did not show the slightest trace of alumina, and none has as yet been discovered in coral skeletons. It is most probable that a large part of the clayey matter found in red clay and the red earth of Bermuda is derived from the disintegration of pumice, which is continually found floating on the surface of the sea. [See Murray, "On the Distribution of Volcanic Débris Over the Floor of the Ocean;" Proc. Roy. Soc. Edin. Vol. IX. pp. 247-261. 1876-1877.] The naturalists of the Challenger found it among the floating masses of gulf weed, and it is frequently picked up on the reefs of Bermuda and other coral islands. The red earth contains a good many fragments of magnetite, augite, felspar, and glassy fragments, and when a large quantity of the rock of Bermuda is dissolved away with acid, a small number of fragments are also met with. These mineral particles most probably came originally from the pumice which had been cast up on the island for long ages (for it is known that these minerals are present in pumice), although possibly some of them may have come from the volcanic rock, which is believed to form the nucleus of the island." The Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger, Narrative of the Cruise, Vol. I. 1885, pp. 141-142.

108

Four bats occur rarely, two being N. American, and two West Indian Species. The Bermuda Islands, by Angelo Heilprin, Philadelphia, 1889.

109

Fourteen species of Spiders were collected by Prof. A. Heilprin, all American or cosmopolitan species except one, Lycosa atlantica, which Dr. Marx of Washington describes as new and as peculiar to the islands. (Heilprin's The Bermudas, p. 93.

111

"Notes on the Vegetation of Bermuda," by H. N. Moseley. (Journal of the Linnean Society, Vol. XIV., Botany, p. 317.)

112

Gigantic Land Tortoises Living and Extinct in the Collection of the British Museum. By A. C. L. G. Günther, F.R.S. 1877.

113

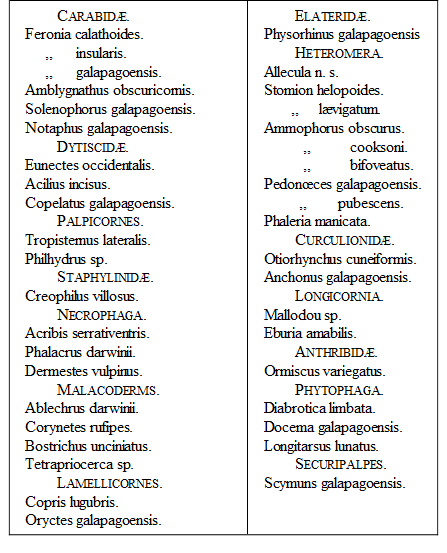

The following list of the beetles yet known from the Galapagos shows their scanty proportions and accidental character; the forty species belonging to thirty-three genera and eighteen families. It is taken from Mr. Waterhouse's enumeration in the Proceedings of the Zoological Society for 1877 (p. 81), with a few additions collected by the U. S. Fish Commission Steamer Albatross, and published by the U. S. National Museum in 1889.

114

Mr. H. O. Forbes, who visited these islands in 1878, increased the number of wild plants to thirty-six, and these belonged to twenty-six natural orders.

115

Juan Fernandez is a good example of a small island which, with time and favourable conditions, has acquired a tolerably rich and highly peculiar flora and fauna. It is situated in 34° S. Lat., 400 miles from the coast of Chile, and so far as facilities for the transport of living organisms are concerned is by no means in a favourable position, for the ocean-currents come from the south-west in a direction where there is no land but the Antarctic continent, and the prevalent winds are also westerly. No doubt, however, there are occasional storms, and there may have been intermediate islands, but its chief advantages are its antiquity, its varied surface, and its favourable soil and climate, offering many chances for the preservation and increase of whatever plants and animals have chanced to reach it. The island consists of basalt, greenstone, and other ancient rocks, and though only about twelve miles long its mountains are three thousand feet high. Enjoying a moist and temperate climate it is especially adapted to the growth of ferns, which are very abundant; and as the spores of these plants are as fine as dust, and very easily carried for enormous distances by winds, it is not surprising that there are nearly fifty species on the island, while the remote period when it first received its vegetation may be indicated by the fact that nearly half the species are quite peculiar; while of 102 species of flowering plants seventy are peculiar, and there are ten peculiar genera. The same general character pervades the fauna. For so small an island it is rich, containing four true land-birds, about fifty species of insects, and twenty of land-shells. Almost all these belong to South American genera, and a large proportion are South American species; but several of the insects, half the birds, and the whole of the land-shells are peculiar. This seems to indicate that the means of transmission were formerly greater than they are now, and that in the case of land-shells none have been introduced for so long a period that all have become modified into distinct forms, or have been preserved on the island while they have become extinct on the continent. For a detailed examination of the causes which have led to the modification of the humming birds of Juan Fernandez see the chapter on Humming Birds in the author's Natural Selection and Tropical Nature, p. 324; while a general account of the fauna of the island is given in his Geographical Distribution of Animals, Vol. II. p. 49.

116

No additions appear to have been made to this flora down to 1885, when Mr. Hemsley published his Report on the Present State of our Knowledge of Insular Floras.

117

Journal of the Linnean Society, Vol. XIII., "Botany," p. 556.

118

Geographical Distribution of Animals, Vol. II. p. 81.

119

St. Helena: a Physical, Historical, and Topographical Description of the Island, &c. By John Charles Melliss, F.G.S., &c. London: 1875.

120

Mr. Marsh in his interesting work entitled The Earth as Modified by Human Action (p. 51), thus remarks on the effect of browsing quadrupeds in destroying and checking woody vegetation.—"I am convinced that forests would soon cover many parts of the Arabian and African deserts if man and domestic animals, especially the goat and the camel, were banished from them. The hard palate and tongue, and strong teeth and jaws of this latter quadruped enable him to break off and masticate tough and thorny branches as large as the finger. He is particularly fond of the smaller twigs, leaves, and seed-pods of the Sont and other acacias, which, like the American robinia, thrive well on dry and sandy soils, and he spares no tree the branches of which are within his reach, except, if I remember right, the tamarisk that produces manna. Young trees sprout plentifully around the springs and along the winter water-courses of the desert, and these are just the halting stations of the caravans and their routes of travel. In the shade of these trees annual grasses and perennial shrubs shoot up, but are mown down by the hungry cattle of the Bedouin as fast as they grow. A few years of undisturbed vegetation would suffice to cover such points with groves, and these would gradually extend themselves over soils where now scarcely any green thing but the bitter colocynth and the poisonous foxglove is ever seen."

121

Coleoptera Sanctæ Helenæ, 1877; Testacea Atlantica, 1878.

122

On Petermann's map of Africa, in Stieler's Hand-Atlas (1879), the Island of Ascension is shown as seated on a much larger and shallower submarine bank than St. Helena. The 1,000 fathom line round Ascension encloses an oval space 170 miles long by 70 wide, and even the 300 fathom line, one over 60 miles long; and it is therefore probable that a much larger island once occupied this site. Now Ascension is nearly equidistant between St. Helena and Liberia, and such an island might have served as an intermediate station through which many of the immigrants to St. Helena passed. As the distances are hardly greater than in the case of the Azores, this removes whatever difficulty may have been felt of the possibility of any organisms reaching so remote an island. The present island of Ascension is probably only the summit of a huge volcanic mass, and any remnant of the original fauna and flora it might have preserved may have been destroyed by great volcanic eruptions. Mr. Darwin collected some masses of tufa which were found to be mainly organic, containing, besides remains of fresh-water infusoria, the siliceous tissue of plants! In the light of the great extent of the submarine bank on which the island stands, Mr. Darwin's remark, that—"we may feel sure, that at some former epoch, the climate and productions of Ascension were very different from what they are now,"—has received a striking confirmation. (See Naturalist's Voyage Round the World, p. 495.)

123

"Notes on the Classification, History, and Geographical Distribution of Compositæ."—Journal of the Linnean Society, Vol. XIII. p. 563 (1873).

124

The Melhaniæ comprise the two finest timber trees of St. Helena, now almost extinct, the redwood and native ebony.

125

Journal of the Linnean Society, 1873, p. 496. "On Diversity of Evolution under one set of External Conditions." Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1873, p. 80. "On the Classification of the Achitinellidæ."

126

"Memoirs on the Coleoptera of the Hawaiian Islands." By the Rev. T. Blackburn, B.A., and Dr. D. Sharp. Scientific Transactions of the Royal Dublin Society. Vol. III. Series II. 1885.

127

See Hildebrand's Flora of the Hawaiian Islands, Introduction, p. xiv.

128

Flora of the Hawaiian Islands, by W. Hildebrand, M.D., annotated and published after the author's death by W. F. Hildebrand, 1888.

129

These are obtained from Hildebrand's Flora supplemented by Mr. Bentham's paper in the Journal of the Linnean Society.

130

Among the curious features of the Hawaiian flora is the extraordinary development of what are usually herbaceous plants into shrubs or trees. Three species of Viola are shrubs from three to five feet high. A shrubby Silene is nearly as tall; and an allied endemic genus, Schiedea, has numerous shrubby species. Geranium arboreum is sometimes twelve feet high. The endemic Compositæ are mostly shrubs, while several are trees reaching twenty or thirty feet in height. The numerous Lobeliaceæ, all endemic, are mostly shrubs or trees, often resembling palms or yuccas in habit, and sometimes twenty-five or thirty feet high. The only native genus of Primulaceæ—Lysimachia—consists mainly of shrubs; and even a plantain has a woody stem sometimes six feet high.

131

Geological Magazine, 1870, p. 155.

132

Transactions of the Edinburgh Geological Society, Vol. I. p. 330.

133

Quarterly Journal of Geological Society, 1850, p. 96.

134

British Association Report, Dundee, 1867, p. 431.

135

The list of names was furnished to me by Dr. Günther, and I have added the localities from the papers containing the original descriptions, and from Dr. Haughton's British Freshwater Fishes.

136

See "The Virginia Colony of Helix nemoralis," T. D. A. Cockerell, in The Nautilus, Vol. III. No. 7, p. 73.

137

I am indebted to Mr. Mitten for this curious fact.

138

The following remarks by Dr. Richard Spruce, who has made a special study of mosses and especially of hepaticæ, are of interest. "From what precedes, I conclude that no existing agency is capable of transporting the germs of our hepatics of tropical type from the torrid zone to Britain, and I venture to suppose that their existence at Killarney dates from the remote period when the vegetation of the whole northern hemisphere partook of a tropical character. If I am challenged to account for their survival through the last glacial period, I reply that, granting even the existence of a universal ice-cap down to the latitude of 40° in America and 50° in Europe, it is not to be assumed that the whole extent, even of land, was perennially entombed 'in thrilling regions of thick-ribbed ice.' Towards the southern margin of the ice the climate was probably very similar to that of Greenland and the northern part of Norway at the present day. The summer sun would have great power, and on the borders of sheltered fjords the frozen snow would disappear completely, if only for a very short period, and I ask only for a month or two, not doubting the capacity of our hepatics to survive in a dormant state under the snow for at least ten months in the year. I have gathered mosses in the Pyrenees where the snow had barely left them on August 2nd; by September 25th they were re-covered with snow, and would not be again uncovered till the following year. The mosses of Killarney might even enjoy a longer summer than this; for the gulf-stream laves both sides of the south-western angle of Ireland, and its tepid waters would exert great melting power on the ice-bound coast, preventing at the same time any formation of ice in the sea itself." This passage is the conclusion of a very interesting discussion on the distribution of hepaticæ in a paper on "A New Hepatic from Killarney," in the Journal of Botany, vol. 25, (Feb. 1887), pp. 33-82, in which many curious facts are given as to the habits and distribution of these curious and beautiful little plants.

139

While these pages are passing through the press I am informed by my friend Mr. W. H. Beeby that in the Shetland Isles, where he has been collecting for five summers, he has found several plants new to the British flora, and a few altogether undescribed. Among these latter is a very distinct species of Hieracium (H. Zetlandicum), which is quite unknown in Scandinavia, and is almost certainly peculiar to the British Islands. Here we have another proof that entirely new species are still to be discovered in the remoter portions of our country.

140

In the first edition of this work the numbers were 400 and 340, showing the great increase of our knowledge during the last ten years, chiefly owing to the researches of Mr. A. H. Everett in Sarawak and Mr. John Whitehead in North Borneo and the great mountain Kini Balu.

141

These are Allocotops, Chlorocharis, Androphilus, and Ptilopyga, among the Timeliidæ; Tricophoropsis and Oreoctistes among the Brachypodidæ; Chlamydochœra among the Campophagidæ.

142

In a letter from Darwin he says:—"Hooker writes to me, 'Miguel has been telling me that the flora of Sumatra and Borneo are identical, and that of Java quite different.'"

143

"On the Geology of Sumatra," by M. R. D. M. Verbeck. Geological Magazine, 1877.

144

Pitta megarhynchus (Banca) allied to P. brachyurus (Borneo, Sumatra, Malacca); and Pitta bangkanus (Banca) allied to P. sordidus (Borneo and Sumatra).

145

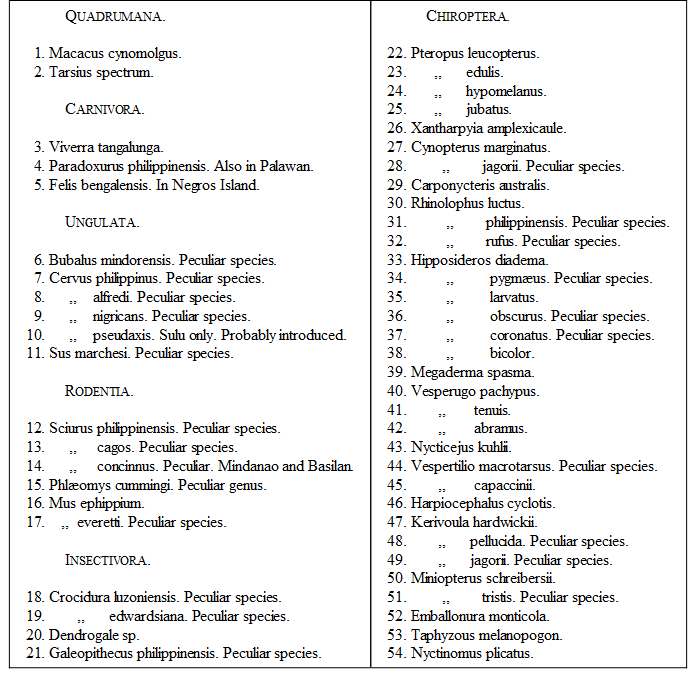

The following list of the mammalia of the Philippines and the Sulu Islands has been kindly furnished me by Mr. Everett.

146

Extracted from Messrs. Blakiston and Pryer's Catalogue of Birds of Japan (Ibis, 1878, p. 209), with Mr. Seebohm's additions and corrections in his Birds of the Japanese Empire 1890. Accidental stragglers are not reckoned as British birds.

147

Mr. Swinhoe died in October, 1877, at the early age of forty-two. His writings on natural history are chiefly scattered through the volumes of the Proceedings of the Zoological Society and The Ibis; the whole being summarised in his Catalogue of the Mammals of South China and Formosa (P. Z. S., 1870, p. 615), and his Catalogue of the Birds of China and its Islands (P. Z. S., 1871, p. 337).

148

Captain Blakiston has shown that the northern island—Yezo—is much more temperate and less peculiar in its zoology than the central and southern islands. This is no doubt dependent chiefly on the considerable change of climate that occurs on passing the Tsu-garu strait.

149

See Dr. J. E. Gray's "Revision of the Viverridæ," in Proc. Zool. Soc. 1864, p. 507.

150

Some of the Bats of Madagascar and East Africa are said to have their nearest allies in Australia. (See Dobson in Nature, Vol. XXX. p. 575.)

151

This view was, I believe, first advanced by Professor Huxley in his "Anniversary Address to the Geological Society," in 1870. He says:—"In fact the Miocene mammalian fauna of Europe and the Himalayan regions contain, associated together, the types which are at present separately located in the South African and Indian provinces of Arctogæa. Now there is every reason to believe, on other grounds, that both Hindostan south of the Ganges, and Africa south of the Sahara, were separated by a wide sea from Europe and North Asia during the Middle and Upper Eocene epochs. Hence it becomes highly probable that the well-known similarities, and no less remarkable differences, between the present faunæ of India and South Africa have arisen in some such fashion as the following: Some time during the Miocene epoch, the bottom of the nummulitic sea was upheaved and converted into dry land in the direction of a line extending from Abyssinia to the mouth of the Ganges. By this means the Dekkan on the one hand and South Africa on the other, became connected with the Miocene dry land and with one another. The Miocene mammals spread gradually over this intermediate dry land; and if the condition of its eastern and western ends offered as wide contrasts as the valleys of the Ganges and Arabia do now, many forms which made their way into Africa must have been different from those which reached the Dekkan, while others might pass into both these sub-provinces."

This question is fully discussed in my Geographical Distribution of Animals (Vol. I., p. 285), where I expressed views somewhat different from those of Professor Huxley, and made some slight errors which are corrected in the present work. As I did not then refer to Professor Huxley's prior statement of the theory of Miocene immigration into Africa (which I had read but the reference to which I could not recall) I am happy to give his views here.

152

The total number of Madagascar birds is 238, of which 129 are absolutely peculiar to the island, as are thirty-five of the genera. All the peculiar birds but two are land birds. These are the numbers given in M. Grandidier's great work on Madagascar.

153

The Ibis, 1877, p. 334.

154

In a paper read before the Geological Society in 1874, Mr. H. F. Blanford, from the similarity of the fossil plants and reptiles, supposed that India and South Africa had been connected by a continent, "and remained so connected with some short intervals from the Permian up to the end of the Miocene period," and Mr. Woodward expressed his satisfaction with "this further evidence derived from the fossil flora of the Mesozoic series of India in corroboration of the former existence of an old submerged continent—Lemuria."

Those who have read the preceding chapters of the present work will not need to have pointed out to them how utterly inconclusive is the fragmentary evidence derived from such remote periods (even if there were no evidence on the other side) as indicating geographical changes. The notion that a similarity in the productions of widely separated continents at any past epoch is only to be explained by the existence of a direct land-connection, is entirely opposed to all that we know of the wide and varying distribution of all types at different periods, as well as to the great powers of dispersal over moderate widths of ocean possessed by all animals except mammalia. It is no less opposed to what is now known of the general permanency of the great continental and oceanic areas; while in this particular case it is totally inconsistent (as has been shown above) with the actual facts of the distribution of animals.

155

Geographical Distribution of Animals, Vol. I., pp. 272-292.

156

The term "Mascarene" is used here in an extended sense, to include all the islands near Madagascar which resemble it in their animal and vegetable productions.

157

For the birds of the Comoro Islands see Proc. Zool. Soc., 1877, p. 295, and 1879, p. 673.

158

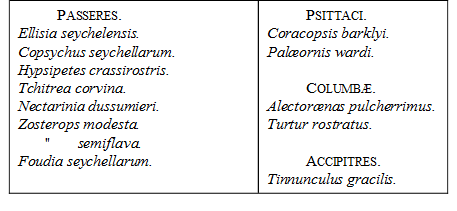

The following is a list of these peculiar birds. (See the Ibis, for 1867, p. 359; and 1879, p. 97.)

159

Specimens are recorded from West Africa in the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Science, Philadelphia, 1857, p. 72, while specimens in the Paris Museum were brought by D'Orbigny from S. America. Dr. Wright's specimens from the Seychelles have, as he informs me, been determined to be the same species by Dr. Peters of Berlin.

160

"Additional Notes on the Land-shells of the Seychelles Islands." By Geoffrey Nevill, C.M.Z.S. Proc. Zool. Soc. 1869, p. 61.

161

In Maillard's Notes sur l'Isle de Réunion, a considerable number of mammalia are given as "wild," such as Lemur mongoz and Centetes setosus, both Madagascar species, with such undoubtedly introduced animals as a wild cat, a hare, and several rats and mice. He also gives two species of frogs, seven lizards, and two snakes. The latter are both Indian species and certainly imported, as are most probably the frogs. Legouat, who resided some years in the island nearly two centuries ago, and who was a closer observer of nature, mentions numerous birds, large bats, land-tortoises, and lizards, but no other reptiles or venomous animals except scorpions. We may be pretty sure, therefore, that the land-mammalia, snakes, and frogs, now found wild, have all been introduced. Of lizards, on the other hand, there are several species, some peculiar to the island, others common to Africa and the other Mascarene Islands. The following list by Prof. Dumeril is given in Maillard's work:—