полная версия

полная версияIsland Life; Or, The Phenomena and Causes of Insular Faunas and Floras

This view of the character of the last glacial epoch appears to correspond very closely with the facts adduced by geologists. The inter-glacial deposits never exhibit any indication of a climate whose warmth corresponded to the severity of the preceding cold, but rather of a partial amelioration of that cold; while it is only the very latest of them, which we may suppose to have occurred when the excentricity was considerably diminished, that exhibit any indications of a climate at all warmer than that which now prevails.57

Probable Date of the Glacial Epoch.—The state of extreme glaciation in the northern hemisphere, of which we gave a general description at the commencement of the preceding chapter, is a fact of which there can be no doubt whatever, and it occurred at a period so recent geologically that all the mollusca were the same as species still living. There is clear geological proof, however, that considerable changes of sea and land, and a large amount of valley denudation, took place during and since the glacial epoch, while on the other hand the surface markings produced by the ice have been extensively preserved; and taking all these facts into consideration, the period of about 200,000 years since it reached its maximum, and about 80,000 years since it passed away, is generally considered by geologists to be ample. There seems, therefore, to be little doubt that in increased excentricity we have found one of the chief exciting causes of the glacial epoch, and that we are therefore able to fix its date with a considerable probability of being correct. The enormous duration of the glacial epoch itself (including its interglacial mild or warm phases), as compared with the lapse of time since it finally passed away, is a consideration of the greatest importance, and has not yet been taken fully into account in the interpretation given by geologists of the physical and biological changes that were coincident with, and probably dependent on, it.

Changes of the Sea-level Dependent on Glaciation.—It has been pointed out by Dr. Croll, that many of the changes of level of sea and land which occurred about the time of the glacial epoch may be due to an alteration of the sea-level caused by a shifting of the earth's centre of gravity; and physicists have generally admitted that the cause is a real one, and must have produced some effect of the kind indicated. It is evident that if ice-sheets several miles in thickness were removed from one polar area and placed on the other, the centre of gravity of the earth would shift towards the heavier pole, and the sea would necessarily follow it, and would rise accordingly. Extreme glacialists have maintained that during the height of the glacial epoch, an ice-cap extended from about 50° N. Lat. in Europe, and 40° N. Lat. in America, continually increasing in thickness, till it reached at least six miles thick at the pole; but this view is now generally given up. A similar ice-cap is however believed to exist on the Antarctic pole at the present day, and its transference to the northern hemisphere would, it is calculated, produce a rise of the ocean to the extent of 800 or 1,000 feet. We have, however, shown that the production of any such ice-cap is improbable if not impossible, because snow and ice can only accumulate where precipitation is greater than melting and evaporation, and this is never the case except in areas exposed to the full influence of the vapour-bearing winds. The outer rim of the ice-sheet would inevitably exhaust the air of so much of its moisture that what reached the inner parts would produce far less snow than would be melted by the long hot days of summer.58 The accumulations of ice were therefore probably confined, in the northern hemisphere, to the coasts exposed to moist winds, and where elevated land and mountain ranges afforded condensers to initiate the process of glaciation; and we have already seen that the evidence strongly supports this view. Even with this limitation, however, the mass of accumulated ice would be enormous, as indeed we have positive evidence that it was, and might have caused a sufficient shifting of the centre of gravity of the earth to produce a submergence of about 150 or 200 feet.

But this would only be the case if the accumulation of ice on one pole was accompanied by a diminution on the other, and this may have occurred to a limited extent during the earlier stages of the glacial epoch, when alternations of warmer and colder periods would be caused by winter occurring in perihelion or aphelion. If, however, as is here maintained, no such alternations occurred when the excentricity was near its maximum, then the ice would accumulate in the southern hemisphere at the same time as in the northern, unless changed geographical conditions, of which we have no evidence whatever, prevented such accumulations. That there was such a greater accumulation of ice is shown by the traces of ancient glaciers in the Southern Andes and in New Zealand, and also, according to several writers, in South Africa; and the indications in all these localities point to a period so recent that it must almost certainly have been contemporaneous with the glacial period of the northern hemisphere.59 This greater accumulation of ice in both hemispheres would lower the whole ocean by the quantity of water abstracted from it, while any want of perfect synchronism between the decrease of the ice at the two poles would cause a movement of the centre of gravity of the earth, and a slight rise of the sea-level at one pole and depression at the other. It is also generally believed that a great accumulation of ice would cause subsidence by its pressure on the flexible crust of the earth, and we thus have a very complex series of agents leading to elevations and subsidences of limited amount, such as seem always to have accompanied glaciation. This complexity of the causes at work may explain the somewhat contradictory evidence as to rise and fall of land, some authors maintaining that it stood higher, and others lower, during the glacial period.

The State of the Planet Mars, as Bearing on the Theory of Excentricity as a Cause of Glacial Periods.—It is well known that the polar regions of the planet Mars are covered with white patches or discs, which undergo considerable alterations of size according as they are more or less exposed to the sun's rays. They have therefore been generally considered to be snow or ice-caps, and to prove that Mars is now undergoing something like a glacial period. It must always be remembered, however, that we are very ignorant of the exact physical conditions of the surface of Mars. It appears to have a cloudy atmosphere like our own, but the gaseous composition of that atmosphere may be different, and the clouds may be formed of other matter besides aqueous vapour. Its much smaller mass and attractive power must have an effect on the nature and extent of these clouds, and the heat of the sun may consequently be modified in a way quite different from anything that obtains upon our earth. Bearing these difficulties and uncertainties in mind, let us see what are the actual facts connected with the supposed polar snows of Mars.60

Mars offers an excellent subject for comparison with the Earth as regards this question, because its excentricity is now a little greater than the maximum excentricity of the Earth during the last million years,—(Mars excentricity 0.0931, Earth excentricity, 850,000 years back, 0.0707); the inclination of its axis is also a little greater than ours (Mars 28° 51′, Earth 23° 27′), and both Mars and the Earth are so situated that they now have the winter of their northern hemispheres in perihelion, that of their southern hemisphere being in aphelion. If, therefore, the physical condition of Mars were the same or nearly the same as that of the Earth, all circumstances combine, according to Dr. Croll's hypothesis, to produce a severe glacial epoch in its southern, with a perpetual spring or summer in its northern, hemisphere; while on the hypothesis here advocated we should expect glaciation at both poles. As a matter of fact Mars has two snow-caps, of nearly equal magnitude at their maximum in winter, but varying very unequally. The northern cap varies slowly and little, the southern varies rapidly and largely.

In the year 1830 the southern snow was observed, during the midsummer of Mars, to diminish to half its former diameter in a fortnight (the duration of such phenomena on Mars being reckoned in Martian months equivalent to one-twelfth of a Martian year). Thus on June 23rd it was 11° 30′ in diameter, and on July 9th had diminished to 5° 46′, after which it rapidly increased again. In 1837 the same cap was observed near its maximum in winter, and was found to be about 35° in diameter.

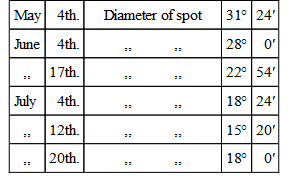

In the same year the northern snow-cap was observed during its summer, and was found to vary as follows:—

We thus see that Mars has two permanent snow-caps, of nearly equal size in winter but diminishing very unequally in summer, when the southern cap is reduced to nearly one third the size of the northern; and this fact is held by Mr. Carpenter, as it was by the late Mr. Belt, to be opposed to the view of the hemisphere which has winter in aphelion (as the southern now has both in the Earth and Mars), having been alone glaciated during periods of high excentricity.61

Before, however, we can draw any conclusion from the case of Mars, we must carefully scrutinise the facts, and the conditions they imply. In the first place, there is evidently this radical difference between the state of Mars now and of the Earth during a glacial period—that Mars has no great ice-sheets spreading over its temperate zone, as the Earth undoubtedly had. This we know from the fact of the rapid disappearance of the white patches over a belt three degrees wide in a fortnight (equal to a width of about 100 miles of our measure), and in the northern hemisphere of eight degrees wide (about 280 miles) between May 4th and July 12th. Even with our much more powerful sun, which gives us more than twice as much heat as Mars receives, no such diminution of an ice-sheet, or of glaciers of even moderate thickness, could possibly occur; but the phenomenon is on the contrary exactly analogous to what actually takes place on the plains of Siberia in summer. These, as I am informed by Mr. Seebohm, are covered with snow during winter and spring to a depth of six or eight feet, which diminishes very little even under the hot suns of May, till warm winds combine with the sun in June, when in about a fortnight the whole of it disappears, and a little later the whole of northern Asia is free from its winter covering. As, however, the sun of Mars is so much less powerful than ours, we may be sure that the snow (if it is real snow) is much less thick—a mere surface-coating in fact, such as occurs in parts of Russia where the precipitation is less, and the snow accordingly does not exceed two or three feet in thickness.

We now see the reason why the southern pole of Mars parts with its white covering so much more quickly and to so much greater an extent than the northern, for the south pole during summer is nearest the sun, and, owing to the great excentricity of Mars, would have about one-third more heat than during the summer of the northern hemisphere; and this greater heat would cause the winds from the equator to be both warmer and more powerful, and able to produce the same effects on the scanty Martian snows as they produce on our northern snow-plains. The reason why both poles of Mars are almost equally snow-covered in winter is not difficult to understand. Owing to the greater obliquity of the ecliptic, and the much greater length of the year, the polar regions will be subject to winter darkness fully twice as long as with us, and the fact that one pole is nearer the sun during this period than the other at a corresponding period, will therefore make no perceptible difference. It is also probable that the two poles of Mars are approximately alike as regards their geographical features, and that neither of them is surrounded by very high land on which ice may accumulate. With us at the present time, on the other hand, geographical conditions completely mask and even reverse the influence of excentricity, and that of winter in perihelion in the northern, and summer in perihelion in the southern, hemisphere. In the north we have a preponderance of sea within the Arctic circle, and of lowlands in the temperate zone. In the south exactly opposite conditions prevail, for there we have a preponderance of land (and much of it high land) within the Antarctic circle, and of sea in the temperate zone. Ice, therefore, accumulates in the south, while a thin coating of snow, easily melted in summer, is the prevalent feature in the north; and these contrasts react upon climate to such an extent, that in the southern ocean, islands in the latitude of Ireland have glaciers descending to the level of the sea, and constant snowstorms in the height of summer, although the sun is then actually nearer the earth than it is during our northern summer!

It is evident, therefore, that the phenomena presented by the varying polar snows of Mars are in no way opposed to that modification of Dr. Croll's theory of the conditions which brought about the glacial epochs of our northern hemisphere, which is here advocated; but are perfectly explicable on the same general principles, if we keep in mind the distinction between an ice-sheet—which a summer's sun cannot materially diminish, but may even increase by bringing vapour to be condensed into snow—and a thin snowy covering which may be annually melted and annually renewed, with great rapidity and over large areas. Except within the small circles of perpetual polar snow there can at the present time be no ice-sheets in Mars; and the reason why this permanent snowy area is more extensive around the northern than around the southern pole may be partly due to higher land at the north, but is perhaps sufficiently explained by the diminished power of the summer sun, owing to its greatly increased distance at that season in the northern hemisphere, so that it is not able to melt so much of the snow which has accumulated during the long night of winter.

CHAPTER IX

ANCIENT GLACIAL EPOCHS, AND MILD CLIMATES IN THE ARCTIC REGIONS

Dr. Croll's Views on Ancient Glacial Epochs—Effects of Denudation in Destroying the Evidence of Remote Glacial Epochs—Rise of Sea-level Connected with Glacial Epochs a Cause of Further Denudation—What Evidence of Early Glacial Epochs may be Expected—Evidences of Ice-action During the Tertiary Period—The Weight of the Negative Evidence—Temperate Climates in the Arctic Regions—The Miocene Arctic Flora—Mild Arctic Climates of the Cretaceous Period—Stratigraphical Evidence of Long-continued Mild Arctic Conditions—The Causes of Mild Arctic Climates—Geographical Conditions Favouring Mild Northern Climates in Tertiary Times—The Indian Ocean as a Source of Heat in Tertiary Times—Condition of North America During the Tertiary Period—Effect of High Excentricity on Warm Polar Climates—Evidences as to Climate in the Secondary and Palæozoic Epochs—Warm Arctic Climates in Early Secondary and Palæozoic Times—Conclusions as to the Climates of Secondary and Tertiary Periods—General View of Geological Climates as Dependent on the Physical Features of the Earth's Surface—Estimate of the Comparative Effects of Geographical and Physical Causes in Producing Changes of Climate.

If we adopt the view set forth in the preceding chapter as to the character of the glacial epoch and of the accompanying alternations of climate, it must have been a very important agent in producing changes in the distribution of animal and vegetable life. The intervening mild periods, which almost certainly occurred during its earlier and later phases, may have been sometimes more equable than even our present insular climate, and severe frosts were probably then unknown. During the four or five thousand years that each specially mild period may have lasted, some portions of the north temperate zone, which had been buried in snow or ice, would become again clothed with vegetation and stocked with animal life, both of which, as the cold again came on, would be driven southward, or perhaps partially exterminated. Forms usually separated would thus be crowded together, and a struggle for existence would follow, which must have led to the modification or the extinction of many species. When the survivors in the struggle had reached a state of equilibrium, a fresh field would be opened to them by the later ameliorations of climate; the more successful of the survivors would spread and multiply; and after this had gone on for thousands of generations, another change of climate, another southward migration, another struggle of northern and southern forms would take place.

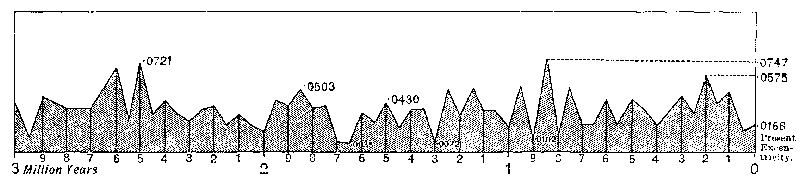

But if the last glacial epoch has coincided with, and has been to a considerable extent caused by, a high excentricity of the earth's orbit, we are naturally led to expect that earlier glacial epochs would have occurred whenever the excentricity was unusually large. Dr. Croll has published tables showing the varying amounts of excentricity for three million years back; and from these it appears that there have been many periods of high excentricity, which has often been far greater than at the time of the last glacial epoch.62 The accompanying diagram has been drawn from these tables, and it will be seen that the highest excentricity occurred 850,000 years ago, at which time the difference between the sun's distance at aphelion and perihelion was thirteen and a half millions of miles, whereas during the last glacial period the maximum difference was ten and a half million miles.

DIAGRAM SHOWING THE CHANGES OF EXCENTRICITY DURING THE LAST THREE MILLION YEARS.

Now, judging by the amount of organic and physical change that occurred during and since the glacial epoch, and that which has occurred since the Miocene period, it is considered probable that this maximum of excentricity coincided with some part of the latter period; and Dr. Croll maintains that a glacial epoch must then have occurred surpassing in severity that of which we have such convincing proofs, and consisting like it of alternations of cold and warm phases every 10,500 years. The diagram also shows us another long-continued period of high excentricity from 1,750,000 to 1,950,000 years ago, and yet another almost equal to the maximum 2,500,000 years back. These may perhaps have occurred during the Eocene and Cretaceous epochs respectively, or all may have been included within the limits of the Tertiary period. As two of these high excentricities greatly exceed that which caused our glacial epoch, while the third is almost equal to it and of longer duration, they seem to afford us the means of testing rival theories of the causes of glaciation. If, as Dr. Croll argues, high excentricity is the great and dominating agency in bringing on glacial epochs, geographical changes being subordinate, then there must have been glacial epochs of great severity at all these three periods; while if he is also correct in supposing that the alternate phases of precession would inevitably produce glaciation in one hemisphere, and a proportionately mild and equable climate in the opposite hemisphere, then we should have to look for evidence of exceptionally warm and exceptionally cold periods, occurring alternately and with several repetitions, within a space of time which, geologically speaking, is very short indeed.

Let us then inquire first into the character of the evidence we should expect to find of such changes of climate, if they have occurred; we shall then be in a better position to estimate at its proper value the evidence that actually exists, and, after giving it due weight, to arrive at some conclusion as to the theory that best explains and harmonises it.

Effects of Denudation in Destroying the Evidence of Remote Glacial Epochs.—It may be supposed, that if earlier glacial epochs than the last did really occur, we ought to meet with some evidence of the fact corresponding to that which has satisfied us of the extensive recent glaciation of the northern hemisphere; but Dr. Croll and other writers have ably argued that no such evidence is likely to be found. It is now generally admitted that sub-aërial denudation is a much more powerful agent in lowering and modifying the surface of a country than was formerly supposed. It has in fact been proved to be so powerful that the difficulty now felt is, not to account for the denudation which can be proved to have occurred, but to explain the apparent persistence of superficial features which ought long ago to have been destroyed.

A proof of the lowering and eating away of the land-surface which every one can understand, is to be found in the quantity of solid matter carried down to the sea and to low grounds by rivers. This is capable of pretty accurate measurement, and it has been carefully measured for several rivers, large and small, in different parts of the world. The details of these measurements will be given in a future chapter, and it is only necessary here to state that the average of them all gives us this result—that one foot must, on an average, be taken off the entire surface of the land each 3,000 years in order to produce the amount of sediment and matter in solution which is actually carried into the sea. To give an idea of the limits of variation in different rivers it may be mentioned that the Mississippi is one which denudes its valley at a slow rate, taking 6,000 years to remove one foot; while the Po is the most rapid, taking only 729 years to do the same work in its valley. The cause of this difference is very easy to understand. A large part of the area of the Mississippi basin consists of the almost rainless prairie and desert regions of the west, while its sources are in comparatively arid mountains with scanty snow-fields, or in a low forest-clad plateau. The Po, on the other hand, is wholly in a district of abundant rainfall, while its sources are spread over a great amphitheatre of snowy Alps nearly 400 miles in extent, where the denuding forces are at a maximum. As Scotland is a mountain region of rather abundant rainfall, the denuding power of its rains and rivers is probably rather above than under the average, but to avoid any possible exaggeration we will take it at a foot in 4,000 years.

Now if the end of the glacial epoch be taken to coincide with the termination of the last period of high excentricity, which occurred about 80,000 years ago (and no geologist will consider this too long for the changes which have since taken place), it follows that the entire surface of Scotland must have been since lowered an average amount of twenty feet. But over large areas of alluvial plains, and wherever the rivers have spread during floods, the ground will have been raised instead of lowered; and on all nearly level ground and gentle slopes there will have been comparatively little denudation; so that proportionally much more must have been taken away from mountain sides and from the bottoms of valleys having a considerable downward slope. One of the very highest authorities on the subject of denudation, Mr. Archibald Geikie, estimates the area of these more rapidly denuded portions as only one-tenth of the comparatively level grounds, and he further estimates that the former will be denuded about ten times as fast as the latter. It follows that the valleys will be deepened and widened on the average about five feet in the 4,000 years instead of one foot; and thus many valleys must have been deepened and widened 100 feet, and some even more, since the glacial epoch, while the more level portions of the country will have been lowered on the average only about two feet.

Now Dr. Croll gives us the following account of the present aspect of the surface of a large part of the country:—

"Go where one will in the lowlands of Scotland and he shall hardly find a single acre whose upper surface bears the marks of being formed by the denuding agents now in operation. He will observe everywhere mounds and hollows which cannot be accounted for by the present agencies at work.... In regard to the general surface of the country the present agencies may be said to be just beginning to carve a new line of features out of the old glacially-formed surface. But so little progress has yet been made, that the kames, gravel-mounds, knolls of boulder clay, &c., still retain in most cases their original form."63