полная версия

полная версияOur Cats and All About Them

Inside the Crystal Palace stood my friend and I. Instead of the noise and struggles to escape, there lay the cats in their different pens, reclining on crimson cushions, making no sound save now and then a homely purring, as from time to time they lapped the nice new milk provided for them. Yes, there they were, big cats, very big cats, middling-sized cats, and small cats, cats of all colours and markings, and beautiful pure white Persian cats; and as we passed down the front of the cages I saw that my friend became interested; presently he said: "What a beauty this is! and here's another!" "And no doubt," said I, "many of the cats you have seen before would be quite as beautiful if they were as well cared for, or at least cared for at all; generally they are driven about and ill-fed, and often ill-used, simply for the reason that they are cats, and for no other. Yet I feel a great pleasure in telling you the show would have been much larger were it not for the difficulty of inducing the owners to send their pets from home, though you see the great care that is taken of them." "Well, I had no idea there was such a variety of form, size, and colour," said my friend, and departed. A few months after, I called on him; he was at luncheon, with two cats on a chair beside him—pets I should say, from their appearance.

This is not a solitary instance of the good of the first Cat Show in leading up to the observation of, and kindly feeling for, the domestic cat. Since then, throughout the length and breadth of the land there have been Cat Shows, and much interest is taken in them by all classes of the community, so much so that large prices have been paid for handsome specimens. It is to be hoped that by these shows the too often despised cat will meet with the attention and kind treatment that every dumb animal should have and ought to receive at the hands of humanity. Even the few instances of the shows generating a love for cats that have come before my own notice are a sufficient pleasure to me not to regret having thought out and planned the first Cat Show at the Crystal Palace.

HABITS

Before attempting to describe the different varieties, I should like to make a few remarks as to the habits and ways of "the domestic cat."

When judging, I have frequently found some of the exhibits of anything but a mild and placid disposition. Some have displayed a downright ferocity; others, on the contrary, have been excessively gentle, and very few but seemed to recognise their position, and submitted quietly to their confinement. This is easily accounted for when persons are accustomed to cats; they know what wonderful powers of observation the cat possesses, and how quickly they recognise the "why and the wherefore" of many things. Take for instance, how very many cats will open a latched door by springing up and holding on with one fore-leg while with the other they press down the latch catch, and so open the door; and yet even more observant are they than that, as I have shown by a case in my "Animal Stories, Old and New," in which a cat opened a door by pulling it towards him, when he found pushing it of no avail. The cat is more critical in noticing than the dog. I never knew but one dog that would open a door by moving the fastening without being shown or taught how to do it. Cats that have done so are numberless. I noticed one at the last Crystal Palace Show, a white cat: it looked up, it looked down, then to the right and then a little to the left, paused, seemed lost in thought, when, not seeing any one about, it crept up to the door, and with its paw tried to pull back the bolt or catch. On getting sight of me, it retired to a corner of the cage, shut its eyes, and pretended to sleep. I stood further away, and soon saw the paw coming through the bars again. This cat had noticed how the cage-door was fastened, and so knew how to open it.

Many cats that are said to be spiteful are made so by ill-treatment, for, as a rule, I have found them to be most affectionate and gentle, and that to the last degree, attaching themselves to individuals, although such is stated not to be the case, yet of this I am certain. Having had several in my house at one time, I found that no two were the "followers" of the same member of my family. But it may be argued, and I think with some degree of justice, Why was this? Was it only that each cat had a separate liking? If so, why? Why should not three or four cats take a liking to the same individual? But they seldom or never do, and for that matter there seems somewhat the same feeling with dogs. This required some consideration, but that not of long duration. For I am sorry to say I rapidly came to the conclusion that it was jealousy. Yes, jealousy! There was no doubt of it. Zeno would be very cossetty, loving, lovable, and gentle, but when Lulu came in and was nursed he retired to a corner and seized the first opportunity of vanishing through the door. As soon as Zillah jumped on my knee and put her paws about my neck, Lulu looked at me, then at her, then at me, walked to the fire, sat down, looked round, got up, went to the door, cried to go out, the door was opened, and–she fled. I thought that Zillah seemed then more than ever—happy.

Though jealousy is one of if not the ruling attributes of the cat, there are exceptions to such a rule. Sometimes it may be that two or more will take to the same person. As an instance of this I had two cats, one a red tabby, a great beauty; Lillah, a short-haired red-and-white cat; the latter and a white long-haired one, named "The Colonel," were great friends, and these associated with a tortoiseshell-and-white, Lizzie. None of these were absolutely house cats, but attended more to the poultry yards and runs, looking after the chicken, seeing that no rats were about or other "vermin," near the coops. Useful cats, very!

Mine was then a very large garden, and generally of an evening, when at home, I used to walk about the numerous paths to admire the beauties of the different herbaceous plants, of which I had an interesting collection. Five was my time of starting on my ambulation, when, on going out of the door, I was sure to find the two first-named cats, and often the third, waiting for me, ready to go wherever I went, following like faithful dogs. These apparently never had any jealous feeling.

Of all the cats Lillah was the most loving. If I stood still, she would look up, and watch the expression of my face. If she thought it was favourable to her, she would jump, and, clinging to my chest, put her fore-paws around my neck, and rub her head softly against my face, purring melodiously all the time, then move on to my shoulder, while "The Colonel" and his tortoiseshell friend Lizzie would press about my legs, uttering the same musical self-complacent sound. Here, there, and everywhere, even out into the road or into the wood, the pretty things would accompany me, seeming intensely happy. When I returned to the house, they would scamper off, bounding in the air, and playing with and tumbling over each other in the fullest and most frolicsome manner imaginable. No! I do not think that Lillah, The Colonel, or Lizzie ever knew the feeling of jealousy. But these, as I said before, were exceptions. They all had a sad ending, coming to an untimely death through being caught in wires set by poachers for rabbits. I have ever regretted the loss of the gentle Lillah. She was as beautiful as she was good, gentle, and loving, without a fault.

It may have been noted in the foregoing I have said that my cats were always awaiting my coming. Just so. The cat seems to take note of time as well as place. At my town house I had a cat named Guadalquiver, which was fed on horseflesh brought to the door. Every day during the week he would go and sit ready for the coming of "the cat's-meat man," but he never did so on the Sunday. How it was he knew on that day that the man did not come I never could discover; still, the fact remains. How he, or whether he, counted the days until the sixth, and then rested the seventh from his watching, is a mystery. A similar case is related of an animal belonging to Mr. Trübner, the London publisher. The cat, a gigantic one, and a pet of his, used to go every evening to the end of the terrace, on which was the house where he resided, to escort Mr. Trübner back to dinner on his arrival from the City, but was never once known to make the mistake of going to meet him on Sundays. And again, how well a cat knows when it is luncheon-time! He or she may be apparently asleep on the tiles, or snugly lying under a bush basking in the sun's warm rays, when it will look up, yawn, stretch itself, get up, and move leisurely towards the house, and as the luncheon-bell rings, in walks the cat, as ready for food as any there.

Most cats are of a gentle disposition, but resent ill-treatment in a most determined way, generally making use of their claws, at the same time giving vent to their feelings by a low growl and spitting furiously. Under such conditions it is best to leave off that which has appeared to irritate them. Dogs generally bite when they lose their temper, but a cat seldom. Should a cat dig her claws into your hand, never draw it backward, but push forward; you thus close the foot and render the claws harmless. If otherwise, you generally lose three to four pieces of skin from your hand; the cat knows he has done it, and feels revenged. Some cats do not like their ears touched, others their backs, others their tails. I have one now (Fritz); he has such a great dislike to having his tail touched that if we only point to it and say "Tail!" he growls, and if repeated he will get up and go out of the room, even though he was enjoying the comfort of his basket before a good fire. By avoiding anything that is known to tease an animal, no matter what, it will be found that is the true way, combined with gentle treatment and oft caressing, to tame and to make them love you, even those whose temper is none of the best. This is equally applicable to horses, cows, and dogs as to cats. Gentleness and kindness will work wonders with animals, and, I take it, is not lost on human beings.

The distance cats will travel to find and regain the home they have been taken from is surprising. One my groom begged of me, as he said he had no cat at home, and he was fond of "the dear thing," but he really wanted to be rid of it, as I found afterwards. He took the poor animal away in a hamper, and after carrying it some three miles through London streets, threw it into the Surrey Canal. That cat was sitting wet and dirty outside the stable when he came in the morning, and went in joyfully on his opening the door, ran up to and climbed on to the back of its favourite, the horse, who neighed a "welcome home." The man left that week.

Another instance, and I could give many more, but this will suffice. It is said that if you wish an old cat to stay you should have the mother with the kitten or kittens, but this sometimes fails to keep her. Having a fancy for a beautiful brown tabby, I purchased her and kitten from a cottager living two miles and a half away. The next day I let her out, keeping the kitten in a basket before the fire. In half an hour mother and child were gone, and though she had to carry her little one through woods, hedgerows, across grass and arable fields, she arrived home with her young charge quite safely the following day, though evidently very tired, wet, and hungry. After two days she was brought back, and being well fed and carefully tended, she roamed no more.

The cat, like many other animals, will often form singular attachments. One would sit in my horse's manger and purr and rub against his nose, which undoubtedly the horse enjoyed, for he would frequently turn his head purposely to be so treated. One went as consort with a Dorking cock; another took a great liking to my collie, Rover; another loved Lina, the cow; while another would cosset up close to a sitting hen, and allowed the fresh-hatched chickens to seek warmth by creeping under her. Again, they will rear other animals such as rats, rabbits, squirrels, puppies, hedgehogs; and, when motherly inclined, will take to almost anything, even to a young pigeon.

At the Brighton Show of 1886 there were two cats, both reared by dogs, the foster-mother and her bantling showing evident signs of sincere affection.

There are both men and women who have a decided antipathy to cats—"Won't have one in the house on any account." They are called "deceitful," and some go as far as to say "treacherous," but how and in what way I cannot discover. Others, on the contrary, love cats beyond all other "things domestic." Of course cats, like other animals, or even human beings, are very dissimilar, no two being precisely alike in disposition, any more than are to be found two forms so closely resembling as not to be distinguished one from the other. To some a cat is a cat, and if all were black all would be alike. But this would not be so in reality, as those well know who are close observers of animal and bird life. Of course the gamekeeper has a dislike to cats, more especially when they "take to the woods," but so long as they are fed, and keep within bounds, they are "useful" in scaring away rats from the young broods of pheasants. What are termed "poaching cats" are clearly "outlaws," and must be treated as such.

TRAINED CATS

That cats may be trained to respect the lives of other animals, and also birds on which they habitually feed, is a well-known fact. In proof of this I well recollect a story that my father used to tell of "a happy family" that was shown many years ago on the Surrey side of Waterloo Bridge. Their abode consisted of a large wire cage placed on wheels. In windy weather the "breezy side" was protected by green baize, so draughts were prevented, and a degree of comfort obtained. As there was no charge for "the show," a box was placed in front with an opening for the purpose of admitting any donations from those who felt inclined to give. On it was written "The Happy Family—their money-box." The family varied somewhat, as casualties occurred occasionally by death from natural causes or sales. Usually, there was a Monkey, an Owl, some Guinea-pigs, Squirrels, small birds, Starlings, a Magpie, Rats, Mice, and a Cat or two. But the story? Well, the story is this. One day, when my father was looking at "the happy family," a burly-looking man came up, and, after a while, said to the man who owned the show: "Ah! I don't see much in that. It is true the cat does not touch the small birds [one of which was sitting on the head of the cat at the time], nor the other things; but you could not manage to keep rats and mice in there as well." "Think not?" said the showman. "I think I could very easily." "Not you," said the burly one. "I will give you a month to do it in, if you like, and a shilling in the bargain if you succeed. I shall be this way again soon." "Thank you, sir," said the man. "Don't go yet," then, putting a stick through the bars of the cage he lifted up the cat, when from beneath her out ran a white rat and three white mice. "Won—der—ful!" slowly ejaculated he of the burly form; "Wonder—ful!" The money was paid.

Cats, properly trained, will not touch anything, alive or dead, on the premises to which they are attached. I have known them to sport with tame rabbits, to romp and jump in frolicsome mood this way, then that, which both seemed greatly to enjoy, yet they would bring home wild rabbits they had killed, and not touch my little chickens or ducklings.

"The Old Lady"

When I built a house in the country, fond as I am of cats, I determined not to keep any there, because they would destroy the birds' nests and drive my feathered friends away, and I liked to watch and feed these from the windows. Things went pleasantly for awhile. The birds were fed, and paid for their keep with many and many a song. There were the old ones and there the young, and oft by the hour I watched them from the window; and they became so tame as scarcely caring to get out of my way when I went outside with more food. But—there is always a but—but one day, or rather evening, as I was "looking on," a rat came out from the rocks, and then another. Soon they began their repast on the remains of the birds' food. Then in the twilight came mice, the short-tailed and the long, scampering hither and thither. This, too, was amusing. In the autumn I bought some filberts, and put them into a closet upstairs, went to London, returned, and thought I would sleep in the room adjoining the closet. No such thing. As soon as the light was out there was a sound of gnawing—curb—curb—sweek!—squeak—a rushing of tiny feet here, there, and everywhere; thump, bump—scriggle, scraggle—squeak—overhead, above the ceiling, behind the skirting boards, under the floor, and—in the closet. I lighted a candle, opened the door, and looked into the repository for my filberts. What a hustling, what a scuffling, what a scrambling. There they were, mice in numbers; they "made for" some holes in the corners of the cupboard, got jammed, squeaked, struggled, squabbled, pushed, their tails making circles; push—push—squeak!—more jostling, another effort or two—squeak—squeak—gurgle—squeak—more struggling—and they were gone. Gone? Yes! but not for long. As soon as the light was out back they came. No! oh, dear no! sleep! no more sleep. Outside, I liked to watch the mice; but when they climbed the ivy and got inside, the pleasure entirely ceased. Nor was this all; they got into the vineries and spoilt the grapes, and the rats killed the young ducks and chickens, and undermined the building also, besides storing quantities of grain and other things under the floor. The result number one was, three cats coming on a visit. Farmyard cats—cats that knew the difference between chickens, ducklings, mice, and rats. Result number two, that after being away a couple of weeks, I went again to my cottage, and I slept undisturbed in the room late the play-ground of the mice. My chickens and ducklings were safe, and soon the cats allowed the birds to be fed in front of the window, though I could not break them of destroying many of the nests. I never noticed more fully the very great use the domestic cat is to man than on that occasion. All day my cats were indoors, dozy, sociable, and contented. At night they were on guard outside, and doubtless saved me the lives of dozens of my "young things." One afternoon I saw one of my cats coming towards me with apparent difficulty in walking. On its near approach I found it was carrying a large rat, which appeared dead. Coming nearer, the cat put down the rat. Presently I saw it move, then it suddenly got up and ran off. The cat caught it again. Again it feigned death, again got up and ran off, and was once more caught. It laid quite still, when, perceiving the cat had turned away, it got up, apparently quite uninjured, and ran in another direction, and I and the cat—lost it! I was not sorry. This rat deserved his liberty. Whether it was permanent I know not, as "Little-john," the cat, remained, and I left.

The cat is not only a very useful animal about the house and premises, but is also ornamental. It is lithe and beautiful in form, and graceful in action. Of course there are cats that are ugly by comparison with others, both in form, colour, and markings; and as there are now cat shows, at which prizes are offered for varieties, I will endeavour to give, in succeeding chapters, the points of excellence as regards form, colour, and markings required and most esteemed for the different classes. I am the more induced to define these as clearly as possible, owing to the number of mistakes that often occur in the entries.

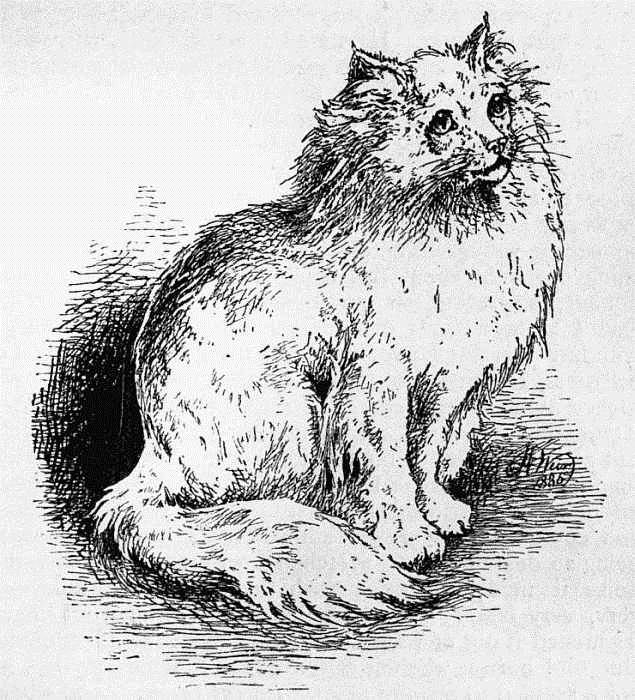

LONG-HAIRED CATS

These are very diversified, both in form, colour, and the quality of the hair, which in some is more woolly than in others; and they vary also in the shape and length of the tail, the ears, and size of eyes. There are several varieties—the Russian, the Angora, the Persian, and Indian. Forty or fifty years ago they used all to be called French cats, as they were mostly imported from Paris—more particularly the white, which were then the fashion, and, if I remember rightly, they, as a rule, were larger than those of the present day. Coloured long-haired cats were then rare, and but little cared for or appreciated. The pure white, with long silky hair, bedecked with blue or rose-colour ribbon, or a silver collar with its name inscribed thereon or one of scarlet leather studded with brass, might often be seen stretching its full lazy length on luxurious woollen rugs—the valued, pampered pets of "West End" life.

A curious fact relating to the white cat of not only the long but also the short-haired breed is their deafness. Should they have blue eyes, which is the fancy colour, these are nearly always deaf; although I have seen specimens whose hearing was as perfect as that of any other colour. Still deafness in white cats is not always confined to those with blue eyes, as I too well know from purchasing a very fine male at the Crystal Palace Show some few years since. The price was low and the cat "a beauty," both in form, coat, and tail, his eyes were yellow, and he had a nice, meek, mild, expressive face. I stopped and looked at him, as he much took my fancy. He stared at me wistfully, with something like melancholy in the gaze of his amber-coloured eyes. I put my hand through the bars of the cage. He purred, licked my hand, rubbed against the wires, put his tail up, as much as to say, "See, here is a beautiful tail; am I not a lovely cat?" "Yes," thought I, "a very nice cat." When I looked at my catalogue and saw the low price, "something is wrong here," said I, musingly. "Yes, there must be something wrong. The price is misstated, or there is something not right about this cat." No! it was a beauty—so comely, so loving, so gentle—so very gentle. "Well," said I to myself, "if there is no misstatement of price, I will buy this cat," and, with a parting survey of its excellences, I went to the office of the show manager. He looked at the letter of entry. No; the price was quite right—"two guineas!" "I will buy it," said I. And so I did; but at two guineas I bought it dearly. Yes! very dearly, for when I got it home I found it was "stone" deaf. What an unhappy cat it was! If shut out of the dining-room you could hear its cry for admission all over the house; being so deaf the poor wretched creature never knew the noise it made. I often wish that it had so known—very, very often. I am satisfied that a tithe would have frightened it out of its life. And so loving, so affectionate. But, oh! horror, when it called out as it sat on my lap, its voice seemed to acquire at least ten cat power. And when, if it lost sight of me in the garden, its voice rose to the occasion, I feel confident it might have been heard miles off. Alas! he never knew what that agonised sound was like, but I did, and I have never forgotten it, and I never shall. I named him "The Colonel" on account of his commanding voice.

One morning a friend came—blessed be that day—and after dinner he saw "the beauty." "What a lovely cat!" said he. "Yes," said I, "he is very beautiful, quite a picture." After a while he said, looking at "Pussy" warming himself before the fire, "I think I never saw one I liked more." "Indeed," said I, "if you really think so, I will give it to you; but he has a fault—he is 'stone' deaf." "Oh, I don't mind that," said he. He took him away—miles and miles away. I was glad it was so many miles away for two reasons. One was I feared he might come back, and the other that his voice might come resounding on the still night air. But he never came back nor a sound.—A few days after he left "to better himself," a letter came saying, would I wish to have him back? They liked it very much, all but its voice. "No," I wrote, "no, you are very kind, no, thank you; give him to any one you please—do what you will with 'the beauty,' but it must not return, never." When next I saw my friend, I asked him how "the beauty" was. "You dreadful man!" said he; "why, that cat nearly drove us all mad—I never heard anything like it." "Nor I," said I, sententiously. "Well," said my friend, "'all is well that ends well;' I have given it to a very deaf old lady, and so both are happy." "Very, I trust," said I.