полная версия

полная версияThe Depot for Prisoners of War at Norman Cross, Huntingdonshire. 1796 to 1816

An entry in the diary of Archdeacon Strong, to whose model of the Block House allusion has already been made, suggests that the work was often bespoken, and that the dyes and other more expensive materials may have been paid for beforehand by the purchaser. The entry is: “23rd October 1801—Drove Margaret to ye Barracks. Bought the model of the Block House and provided the Mahogany. £1 11s. 6d., sergt. 1s., man 1s., soldier 1s. 3d.” The venerable gentleman’s diary contains other items throwing light on the price received by the prisoners for the fruit of their labours. From one such entry we learn that the Archdeacon, in 1811, paid two guineas for a marquetry picture of the Minster, now the property of his grandson, Colonel Strong.

The straw undoubtedly was bought from outside, and there can be no doubt that what applied to this “raw product” applied to other material and to tools necessary for the production of the works, by the sale of which we have Commissioner Serle’s authority for the prevalent opinion that within a few years of their confinement many of the prisoners had made one hundred guineas.

The great speciality of the Norman Cross prisoners was straw marquetry work, in which they greatly excelled, producing beautiful pictures in straw, and manufacturing and decorating with varied, elaborate, and most artistic designs, cabinets, work-boxes, desks, tea-caddies, dressing-boxes, small boxes of various shapes, hand fire-screens, snuff-boxes, silk holders, etc., etc. It would appear that occasionally the prisoners, skilled in this work, were applied to, to decorate with their marquetry, articles such as picture frames, etc. There have recently been presented to the museum of the Peterborough Natural History and Antiquarian Society, by a friend, through Mr. C. Dack, the Curator, fourteen examples of straw marquetry work, among them a case containing a telescope which was bought at the sale of Captain John Kelly, son of Major Kelly, the last Brigade-Major at the barracks. This resembles an ordinary telescope, except that the tube is covered by straw marquetry, the work of a prisoner, instead of the usual leather casing.

The illustrations, which are reproductions of very perfect photographs taken by Mr. A. C. Taylor of articles in the museum, show more convincingly than any verbal description can, the beauty of the designs and the workmanship of the most artistic of these articles, although they fail to show the colour effects produced by the use of dyed straws.

In all there are in the museum 162 examples of straw work, almost all of them being marquetry. There is one straw bonnet which was found in the roof of a house at Cottesmore, twenty-five miles from Norman Cross. How it is identified as Norman Cross work the author does not know, but if made at Norman Cross, it was probably carried away surreptitiously by a smuggler and hidden until a safe opportunity for its sale offered itself. The manufacture in the prison of hats and bonnets was forbidden.

Returning to the legitimate and more artistic work of the prisoners, it may be mentioned that the joinery and cabinet-makers’ work of the various articles made for decoration by the straw workers, most of it, as it is believed done in the prison, was of the best quality, and has made a durable base for the straw marquetry with which the experts overlaid them, in beautiful formal patterns with delicately coloured designs, human figures, birds, flowers, etc., interspersed. Pictures on panel, in the same material, are also found in private houses in the neighbourhood, but the most beautiful are now in the museum. One, a view of the west front of Peterborough Cathedral, bearing the name De la Porte as the artist who constructed it, has been already mentioned, and in the course of the researches made for the purpose of this history, the owner of the name has been identified with Corporal Jean De la Porte, one of the French heroes who on the 12th October 1805 fought against the British at Trafalgar, where Nelson died, but not before he had settled the question of our nation’s supremacy on the sea. J. De la Porte was taken in L’Intrépide. 55

Another manufacture carried on very extensively by the prisoners was bone work, the cooking-houses afforded the material, and in the Peterborough Museum alone are 256 examples of the work produced by the skill and industry of the prisoners in their manipulation of the bones of the animals which were killed for their ration (of these 256 articles, 33 were the gift of Mr. C. Dack’s friend already referred to). With this material and the simplest tools were produced works, as a rule, more crude and of less artistic design than the works of the marquetry artists, but demanding skill, delicacy of touch, and untiring patience on the part of the artificer, who must in some instances have spent months and even years over their execution. Such a work was that represented in the illustration. It appears to represent a stage, on which are placed various figures.

The largest specimen in the museum of this class of work is the model of a large château, with various mechanically working figures. It was presented by H. L. C. Brassey, M.P., on the recommendation of Mr. C. Dack, the curator of the museum, who says that he has evidence of its authenticity as a work of the Norman Cross prisoners. There are nine beautiful models of ships, most elaborate models of the guillotine (Plate X, p. 102), crowded with little carved figures of soldiers, the victim, the executioner, etc.; watch-stands, domino boxes, many elaborately carved, a domino and cribbage box combined, containing cards, dice and teetotum; chessmen, fans, work-boxes, working-models of the spinning-jenny, and so on, down to tooth-picks, tobacco stoppers, apple scoops, and such small articles.

The desk in the illustration (Plate XV) is one of the 256 articles made from bone which are in the Peterborough Museum.

The group of figures on a platform (Plate XVI, Fig. 1), is one of many such mechanical toys or ornaments known to the author. This is beautifully preserved, having been kept in the box in which it was purchased for many years. When the lower wheel below the platform is turned, by an arrangement of the threads passing over the wheels, the various figures move, the lady in the centre turns the winding-wheel, the child moves forward, the soldier and the lady waltz, the mother tosses her baby, turning her head to look at it, while the lady on the left prepares the tea. The owner of this ornament is the grandson of its purchaser.

Some of the bone articles have parts that have been turned; one of the minor exhibits is a pair of turned cribbage pegs. This work does not prove that there was a lathe in the prison. The prisoner who made the carved cribbage box would easily get the turned pegs finished off outside.

Another material in which the prisoners worked was horn, but the examples are few. H. Akin, late Secretary of the Society of Arts, writing on “Horn and Tortoise-shell,” 56 says, “Another branch of industry practised by the prisoners was horn work, and here again the artistic ingenuity of the French was manifest at Norman Cross. (The solid tips were made into handles, buttons, ornaments, etc.) Of the long pieces, after certain processes the principal uses were for combs, the chief manufactury of which was at Kenilworth, but combs ornamented with open work were not made in England, on account of the expense, being imported in great quantities from France.” 57 The passage quoted shows that at the date it was written (1840) the Norman Cross bone work was well known. The specimens in the Museum are very few; they include horn fans, three of which were a part of the gift of Mr. Dack’s friend.

Of articles made from wood there are but few in the museum. The most important is a beautifully carved figure of a Roman warrior, 11 inches high on a bone carved pedestal; others are models of the Block House (Plate III, p. 22), models of ships, domino and other boxes, and one wooden block with the name Louis Chartiée (sic) carved in relief. This will be referred to later on. It will be remembered that M. Charretie (whose name was not always spelt correctly, even in official documents) was the commissary for the French prisoners in England in the early days of Norman Cross.

One other material in which the French prisoners worked was paper. It was used to make artificial flowers, and there are two examples in the museum (Plate XVI, Fig. 2). One, a group representing roses, sweet peas, passion flowers, a most valuable specimen, was among the gifts of Mr. C. Dack’s friend; the other (Plate XVI, Fig. 3) was presented by the late Dr. L. Cane of Peterborough, and has an authentic history. Another form in which paper was used was its application in strips, one eighth of an inch wide, of stiff, gold-edged or coloured paper, to a surface prepared with flanges, projecting to the exact width of the strip; the latter was wound on its cut edge in a pattern of graceful curves, the cut edge being glued to the wood or other material forming the base and the gilt edge being left on the surface. In order to complete the pattern, the interstices left between the convolutions were at various parts of the design filled with solidly rolled strips of coloured paper, giving the appearance of cloisonnée work; at other parts a different device was adopted to give variety, a plate of tinfoil, cut to the shape of a leaf or other pattern, was fixed on the foundation before the coils of paper were glued to it, the reflection giving the appearance of mother-of-pearl. 58 A pair of wine slides and a box are the only specimens of the work in the museum, but three other examples, all of them tea-caddies, are known to the writer. 59

The collection in the Peterborough Museum embraces 450 articles manufactured by the prisoners of war, but possibly not all at Norman Cross. It is probably the largest and finest collection in the world, although the model of the Norman Cross Depot in the Musée de l’Armée, Hôtel des Invalides, Paris, excels, both in its size and in the multiplicity of its detail, any one object in the Peterborough Museum. A photograph of this beautiful model (Plate XX, p. 251) is reproduced in the final chapter of this work, where it naturally finds a place, as it represents the departure of the first detachment of the freed prisoners at the final closing of the Depot. The size of the model will be appreciated from the measurements of each of the caserns, which are as follows: length 169 millimetres, approximately 7 inches; width 70 millimetres, approximately 3 inches; height, from ground to eave, 9 centimetres, approximately 4½ inches.

The workers in straw did not confine their attention to these works of art, they also manufactured straw hats and bonnets, although this handicraft was forbidden from the earliest years of the prison’s existence. The manufacture of straw plait was not forbidden until a later date. There was good reason for these interdicts. This branch of trade was a staple industry of the neighbouring counties of Bedford and Hertford, and to a less extent of Huntingdonshire and Northamptonshire, and the prisoners who were fed by the State were competing on advantageous terms with those who had to contribute to their maintenance, but, worse than this, in the eyes of the Government, they were actually defrauding the Revenue. As the war continued year after year, fresh articles had to be taxed to find the funds for carrying it on. In his Budget speech on 5th April 1802, the Chancellor of the Exchequer alluded to the Schedule of 5,000 articles liable to duty. 60 Among these were straw hats and bonnets. 61

Various accounts have been given of the part which was taken by the outside accomplices of the prisoners, some speaking of their smuggling the plait in, and others of their smuggling it out. That they did smuggle in “the Straw Manufactured for the purpose of being made into Hats, Bonnets, etc., by which the Revenue of our country is injured, and the poor who exist by that branch of trade would be turned out of employ,” is proved by Sir Rupert George’s letter, 62 printed in a report to the House of Commons. In this letter the Commissioner of the Transport Office goes on to say, “I must observe that this, the manufactured straw plait is the only article which the prisoners are prevented from manufacturing.” This letter is dated 19th March 1808; its discovery destroys an illusion which the inscription publicly displayed in the Town of Luton, beneath Mr. Arthur Cooke’s beautiful picture, would establish, if its historical accuracy were not disproved.

The picture hangs in the Free Library of Luton, with the following inscription attached:

“Plait Merchants trading with the French Prisoners of War at Yaxley 1806–1815. Painted by A. C. Cooke. Presented to the Town of Luton by J. C. Kershaw, Esq.”

In those years, Sir Rupert George’s letter, which only came to light in 1909, after the picture was painted, proves (without further evidence) that the trade was illicit, that no such open dealing could have taken place at that time, that it was an underground trade, carried on by the help of middlemen and outside accomplices. 63 The gesticulating Frenchman and the keen, critical merchant at that time never met; between the one in the prison and the other miles away came the old woman, to be mentioned directly, and others like her. Soldiers, the guards of the mail coaches, innkeepers, hostlers, and tradesmen in Stilton and elsewhere were not above purchasing the smuggled goods and disposing of them to the Luton merchants.

The existence of Macgregor’s plan of the Depot, and various documents examined in the Record Office, also show that the date affixed to the picture makes it an historical anachronism, the market in the years named being held outside the brick wall surrounding the prison, out of sight of any stockade fencing, and with permanent stalls of brick and slate built against the wall in the eastern embrasure. In the earlier days of the Depot’s existence, although the sale of straw hats and bonnets was forbidden, such a scene as that depicted might possibly have been witnessed. Mr. Cooke will doubtless insist on the prompt alteration of the dates in the inscription describing the picture.

The artist has kindly permitted the writer to introduce here a photogravure of this work of art. The typical figures alive on the canvas each telling its own tale, the beautiful grouping, and the background in which they are placed, present to the eye of the reader what this work strives to convey to his mind in words. An artist’s licence doubtless sanctions the introduction of a tree, the light open-paled fence, instead of the stockade posts and other minor details which conflict with the precise ideas arrived at by the writer, who feels constrained to notice these little inaccuracies.

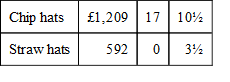

Included in the Public Revenue Accounts for 1798, 64 among the returns of produce are specified:

On the 18th March 1806 the House of Commons resolved to go into committee to consider the question of charging a duty on imported straw plait. After formal stages, it was resolved, 26th June, to levy a duty of 7s. per lb. avoirdupois of plaiting for hats or bonnets, £1 16s. on every dozen hats or bonnets not exceeding 22 inches in diameter, £3 12s. on every dozen exceeding 22 inches in diameter. The Act received the royal assent on the 10th July. After this date the sale of straw plait was interdicted as had previously been the sale of hats, the hats and the plait made at Norman Cross being alike regarded as foreign productions and liable to tax.

In official documents constant reference is made to this traffic in the plait as illegal and defrauding the Revenue.

George Borrow’s eloquent description of “the straw plait hunts” (poor little ten-year-old George Borrow—his sympathetic soul went out to the captives!) has helped to throw the glamour of romance over the irregular proceedings of the Frenchmen, whom we were maintaining in our prisons, and whom we would gladly have restored to their own country if only we could be met on fair terms.

Persons in the neighbourhood, soldiers from the barracks, and others were accessories in the illicit trade in straw plait. They would conceal it about their persons, wrap it round their bodies, etc. They assisted in two ways, they helped to get the straw into the prison and to carry the manufactured article out. 65

Although the interdict on the traffic was issued even before the articles were taxed, in the interests of the trade and of the workers in the district, so profitable was the illicit traffic to those who took part in it, that the fact that they were interfering with the living of their own countrymen and women had no deterrent effect, and such was the influence of the merchants and the various persons in the neighbourhood engaged in the trade that it was difficult to get convictions. To get the straw ready cut into proper lengths into the hands of the prisoners was doubtless more easy than to get a sack of straw thrown over the prison wall, carried across the open spaces up to the inner stockade fence, and again thrown over them into the court of the caserns. This proceeding must have needed several soldier accomplices, some giving active assistance and others closing their eyes to what was going on. These men, when detected, had severe punishment, receiving as many as 500 lashes. Three civilians tried at Huntingdon for being engaged in the traffic in 1811 were convicted and sentenced to imprisonment, one for twelve and the two others for six months.

That the trade in straw plait was an extensive one, and that the prisoners effected an improvement both in the character of the plait and the method of producing it, are almost universally accepted facts. In Davis’ History of Luton, pp. 152–3, is a small section which, although written under the mistaken conception that the French prisoners were at Norman Cross only about eight years—1806–14—and that the merchants during that period went to the barracks to purchase the plait, is probably correct in saying that the trade is indebted to these prisoners for the invention of the simple machine for splitting the straw from which such great and beautiful varieties of plait are made. There are two descriptions of machines called splitters.

The writer of an article in Chambers’ Journal, 66 after instancing industries introduced at various places where they were confined by the prisoners of war, such as the knitting worsted gloves at Chesterfield, goes on to say:

“At Norman Cross they revolutionised the straw plaiting trade. Up to their time the straw was plaited whole and called ‘Dunstable,’ but it was a case of necessity being the mother of invention. Their supply not being equal to the demand, one of them invented the ‘splitter.’ This consists of a small wheel, inserted in a mahogany frame, and furnished in the centre with small sharp divisions like spokes. From the axle a small spike protrudes, on which a straw pipe is placed and pushed through, the cutters or spokes dividing it into as many strips as required. By this contrivance the plait could be made much finer, the strips could be used alternately with the outside and inside, or even the inside alone, which is white, and is known in the trade as ‘rice’ straw.”

For a full description of this little implement called the splitter, the reader is referred to the article, “Straw Plaiting and French Prisoners,” by Maberly Phillips, F.S.A., The Connoisseur, vol. xxvii., No. 105.

There are in the Peterborough Museum three examples of different varieties of straw splitters. The neat splitting of the straw was possibly not an invention of the prisoners, although it may have come from France. If it were, it is likely that it was not originally contrived for the manufacture of straw plait, but for the straw used in the marquetry, for which purpose it had to be most carefully prepared, and much of it dyed, with material bought in the market.

From the first opening of the prison, straw work was carried on, although in going through the copy in the Record Office of the register of deaths of those who died in the prison, the late Mr. W. B. Sands, Secretary to the association “L’entente cordiale,” and Mrs. Sands, the present acting Secretary, found that very few of the prisoners, whose names and native places were there entered, came from districts in France where this industry was prevalent. So long as the work was confined to ornamental articles, which paid no import duty, it was allowed, but as early as June 1798 an order was issued prohibiting the introduction of any more straw for the manufacture of hats, and ten years later, in June 1808, there is a record that the general market was put under severe restrictions owing to the illicit traffic in straw. This restriction evidently pressed harshly upon the marquetry workers, for we find, on the 11th November 1808, a letter from the Admiralty Board, saying that “If the manufacture of Plait could be effectually prevented, it is not our wish to prohibit the Prisoners from making baskets, boxes, or such like articles of straw. The Prisoners might purchase wool and make frocks, for their own use; if any should be sold, a stop was to be put to the manufacture.”

On the 20th March 1809 a shop was opened for each building, with two prisoners as salesmen, all articles being marked with the price and the owner’s name. The salesmen were to be searched going and returning, and if any prohibited article were found, the shops were to be closed. In July of the same year, notwithstanding the precautions, the illicit traffic was so rampant that stringent orders were issued to entirely close one quadrangle for a month. This was in consequence of the Admiralty having intercepted a letter enclosing a £10 bill, the proceeds of a sale at Thame of illicit articles made by the prisoners at Norman Cross.

The sympathies of the outside public appear to have been with those who made the plait and those who sold it contrary to the law, as was usually the case in the districts on the coast where smugglers carried on their trade. The number of those actually engaged in the traffic and making profit out of it was no doubt very considerable. A trial which took place at Huntingdon in 1811 shows the number of hands through which a packet of plait went before it reached the Luton bonnet makers. Four Stilton men, one the ostler at the Bell Inn, who had acted as intermediaries between the Luton merchants and the prisoners, had bribed the soldier who came in contact with the prisoners to take packets of straw cut to the proper length into the prison, and to bring the manufactured plait out; they were all four convicted and punished. Whether the soldier, who was acting in defiance of a special order by the Duke of York, escaped punishment is not known; they were paid by the Stilton men a shilling for getting the straw in and another for getting the plait out. The merchants, no doubt, took care to escape the hands of the law.

In The Stamford Mercury of 12th February 1812 are related the particulars of an outrage on Sergeant Ives of the West Essex Militia at that time stationed at the Depot. He was stopped between Stilton and Norman Cross by a number of men, knocked down and robbed of his watch and money, his jaws were wrenched open and a piece of his tongue cut off. It was said that the sergeant had been active in stopping the plait trade and that this led to the outrage. Another possible explanation of this outrage is suggested in a later chapter on the health of the prisoners.

The Bishop of Moulins, of whom more shortly, was living at Stilton, and although he has been raised by tradition to a very exalted position of righteousness, he got into trouble by allowing his servant to become an outside agent for those engaged in this illicit traffic. The good Bishop applied to the Government for another young prisoner to take the place of Jean Baptiste David, and, his request being refused, he pressed into his service the intercession of Lord Fitzwilliam, who had already befriended him in other ways. The letter from Mr. Commissioner George, to the Secretary to the First Lord of the Admiralty, throws light not only on the particular case of the Bishop, but on this question of the straw plait manufacture in general, and it is therefore transcribed at length in the text.