полная версия

полная версияThe Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

It must be emphasized, moreover, that in many of the university towns there were also preparatory schools. Courses were not regularly organized until well on in the Thirteenth Century, but younger brothers and friends of students as well as of professors would not infrequently be placed under their care and thus be enabled to receive their preparation for university work. At Paris, Robert Sorbonne founded a preparatory school for that institution under the name of the College of Calvi. Other colleges of this kind also existed in Paris. This custom of having a preparatory school in association with the university has not been abandoned even in our own day, and it has some decided advantages from an educational standpoint, though perhaps these are not enough to balance certain ethical disadvantages almost sure to attach to such a system, disadvantages which ultimately led in the Middle Ages to the prohibition that young students should be taken at the universities under any pretext.

The presence of these young students in university towns probably did add considerably to the numbers reported as in attendance. It must not be thought, however, that there were no formal preparatory schools quite apart from university influence. This thought has been the root of more misunderstanding of the medieval system of education than almost any other. As a matter of fact there were preliminary and preparatory schools, what we would now call academies and colleges, in connection with all of the important monasteries and with every cathedral. Schools of less importance were required by a decree of a council held at the beginning of the Thirteenth Century to be maintained in connection with every bishop's church. During the Thirteenth Century there were some twenty cathedrals in various parts of England; each one had its cathedral school. Besides these there were at least as many important abbeys, nearly a dozen of them immense institutions, in which there were fine libraries, large writing rooms, in which copies of books were being constantly made, many of the members of the communities of which were university men, and around which, therefore, there clung an atmosphere of bookishness and educational influence that made them preparatory schools of a high type. The buildings themselves were of the highest type of architecture; the community life was well calculated to bring out what was best in the intellectuality of members of the community, and, then, there was a rivalry between the various religious orders which made them prepare their men well in order that they might do honor to the order when they had the opportunity later, as most of those who had the ability and the taste actually did have, to go to one or other of the universities.

This system of preparatory schools need not be accepted on the mere assumption that the monasteries and churches must surely have set about such work, because there is abundant evidence of the actual establishment and maintenance of such schools. With regard to the monasteries there can be no doubt, because it was the members of the religious orders who particularly distinguished themselves at the universities, and the histories of Oxford, Cambridge, and Paris are full of their accomplishments. They succeeded in obtaining the right to have their own houses at the universities and to have their own examinations count in university work, in order that they might maintain their influence over the members of the orders during the precious formative period of their intellectual life. With regard to the church schools there is convincing evidence of another kind.

In the chapter on the foundation of City Hospitals we have detailed on the authority of Virchow all that Innocent III. accomplished for the hospital system of Europe. This chapter was published originally in the form of a lecture from the historical department of the Medical School of Fordham University and a reprint of it was sent to a distinguished American educator well known for his condemnation of supposed church intolerance in the matter of education and scientific development. He said that he was glad to have it because it confirmed and even broadened the idea that he had long cherished, that the Church had done more for Charity during the despised Middle Ages than national governments had ever been able to accomplish since, though it was all the more surprising to him that it should not have under the circumstances, done more for education, since this might have prevented some of the ills that charity had afterward to relieve. This expression very probably represents the state of mind of very many scholars with regard to this period. The Church is supposed to have interested herself in charity almost to the exclusion of educational influence. Charity is of course admitted to be her special work, yet these scholars cannot help but regret that more was not done in social prophylaxis by the encouragement of education.

In the light of this almost universal expression it is all the more interesting to find that such opinions are founded entirely on a lack of knowledge of what was done in education, since the same Pope, in practically the same way and by the exertion of the same prestige and ecclesiastical authority, did for education just what he did for charity in the matter of the hospitals and the ailing poor. Virchow, as we shall see, declared that to Innocent III. is due the foundation of practically all the city hospitals in Europe. If the effect of certain of the decrees issued in his papacy be carefully followed, it will be found that practically as many schools as hospitals owe their origin to his beneficent wisdom and his paternal desire to spread the advantages of Christianity all over the civilized world. This policy with regard to the hospitals led to the foundation before the end of the century of at least one hospital in every diocese of all the countries which were more closely allied with the Holy See. There is extant a decree issued by the famous council of Lateran, in 1215, a council in which Innocent's authority was dominant, requiring the establishment of a Chair of Grammar in connection with every cathedral in the Christian world. This Chair of Grammar included at least three of the so-called liberal arts and provided for what would now be called, the education of a school preparatory to a university.

Before this, Innocent III,2 who had himself received the benefit of the best education of the time, having spent some years at Rome and later at Paris and at Bologna, had encouraged the sending of students to these universities in every way.

CATHEDRAL (YORK)

CATHEDRAL (LINCOLN)

Bishops who came to Rome were sure to hear inculcated the advisability of a taste for letters in clergymen, hear it said often enough that such a taste would surely increase the usefulness of all churchmen. Schools had been encouraged before the issuance of the decree. This only came as a confirmatory document calculated to perpetuate the policy that had already been so prominently in vogue in the church for over fifteen years of the Pope's reign. It was meant, too, to make clear to hesitant and tardy bishops, who might have thought that the papal interest in education was merely personal, that the policy of the church was concerned in it and recalled them to a sense of duty in the matter, since the ordinary enthusiasm for letters, even with the added encouragement of the Pope, did not suffice to make them realize the necessity for educational establishments.

The institution of the schools of grammar in connection with cathedrals was well adapted to bring about a definite increase in the opportunities for book learning for those who desired it. In connection with the cathedrals there was always a band of canons whose duty it was to take part in the singing of the daily office. Their ceremonial and ritual duties did not, however, occupy them more than a few hours each day. During the rest of the time they were free to devote themselves to any subject in which they might be interested and had ample time for teaching. The requirement that there should be at least a school of grammar in connection with every cathedral afforded definite opportunity to such of these ecclesiastics as had intellectual tastes to devote themselves to the spread of knowledge and of culture, and this reacted, as can be readily understood, to make the whole band of canons more interested in the things of the mind, and to make the cathedral even more the intellectual center of the district than might otherwise have been the case.

For the metropolitan churches a more far-reaching regulation was made by this same council of Lateran under the inspiration of the Pope himself. These important Archiepiscopal cathedrals were required to maintain professors of three chairs. One of these was to teach grammar, a second philosophy, and a third canon law. Under these designations there was practically included much of what is now studied not only in preparatory schools but also at the beginning of University courses. The regulation was evidently intended to lead eventually to the formation of many more universities than were then in existence, because already it had become clear that the traveling of students to long distances and their gathering in such large numbers in towns away from home influences, led to many abuses that might be obviated if they could stay in their native cities, or at least did not have to leave their native provinces. This was a far-seeing regulation that, like so many other decrees of the century, manifests the very practical policy of the Pope in matters of education as well as charity. As a matter of fact this decree did lead to the gradual development of about twenty universities during the Thirteenth Century, and to the establishment of a number of other schools so important in scope and attendance that their evolution into universities during the Fourteenth Century became comparatively easy. This formal church law, moreover, imposed upon ecclesiastical authorities the necessity for providing for even higher education in their dioceses and made them realize that it was entirely in sympathy with the church's spirit and in accord with the wish of the Father of Christendom, that they should make as ample provision for education as they did for charity, though this last was supposed to be their special task as pastors of the Christian flock.

All this important work for the foundation of preparatory schools in every diocese and of the preliminary organization of teaching institutions that might easily develop into universities, as they actually did in a score of cases in metropolitan cities, was accomplished under the first Pope of the Thirteenth Century, Innocent III. His successors kept up this good work. Pope Honorius III., his immediate successor, went so far in this matter as to depose a bishop who had not read Donatus, the popular grammarian of the time. The bishop evidently was considered unfit, as far as his mental training went, to occupy the important post of head of a diocese. Pope Gregory IX., the nephew of Innocent III., was one of the most important patrons of the study of law in this period (see Legal Origins in Other Countries), and encouraged the collection of the decrees of former Popes so as to make them available for purposes of study as well as for court use. He is famous for having protected the University of Paris during some of the serious trouble with the municipal authorities, when the large increase of the number of students in attendance at the University had unfortunately brought about strained relations between town and gown.

Pope Innocent IV. by several decrees encouraged the development of the University of Paris, increased its rights and conferred new privileges. He also did much to develop the University of Toulouse, and especially to raise its standard and make it equal to that of Paris as far as possible. The patronage of Toulouse on the part of the Pope is all the more striking because the study of civil law was here a special feature and the ecclesiastical authorities were often said to have looked askance at the rising prominence of civil law, since it threatened to diminish the importance of canon law; and the cultivation of it, only too frequently, seemed to give rise to friction between civil and ecclesiastical authorities. While the pontifical court of Innocent IV. was maintained at Lyons it seemed, according to the Literary History of France,3 more like an academy of theology and of canon law than the court of a great monarch whose power was acknowledged throughout the world, or a great ecclesiastic who might be expected to be occupied with details of Church government.

Succeeding Popes of the century were not less prominent in their patronage of education. Pope Alexander IV. supported the cause of the Mendicant Friars against the University of Paris, but this was evidently with the best of intentions. The mendicants came to claim the privilege of having houses in association with the university in which they might have lectures for the members of their orders, and asked for due allowance in the matter of degrees for courses thus taken. The faculty of the University did not want to grant this privilege, though it was acknowledged that some of the best professors in the University were members of the Mendicant orders, and we need only mention such names as Albertus Magnus and St. Thomas Aquinas from the Dominicans, and St. Bonaventure, Roger Bacon and Duns Scotus from the Franciscans, to show the truth of this assertion. To give such a privilege seemed a derogation of the faculty rights and the University refused. Then the Holy See interfered to insist that the University must give degrees for work done, rather than merely for regulation attendance. The best possible proof that Pope Alexander cannot be considered as wishing to injure or even diminish the prestige of the University in any way, is to be found in the fact that he afterwards sent two of his nephews to Paris to attend at the University.

All these Popes, so far mentioned, were not Frenchmen and therefore could have no national feeling in the matter of the University of Paris or of the French universities in general. It is not surprising to find that Pope Urban IV., who was a Frenchman and an alumnus of the University of Paris, elevated many French scholars, and especially his fellow alumni of Paris, to Church dignitaries of various kinds. After Urban IV., Nicholas IV. who succeeded him, though once more an Italian, founded chairs in the University of Montpelier, and also a professorship in a school that it was hoped would develop into a university at Gray in Franche Comte. In a word, looked at from every point of view, it must be admitted that the Church and ecclesiastical authorities were quite as much interested in education as in charity during this century, and it is to them that must be traced the foundation of the preparatory schools, as well as the universities, and the origin and development of the great educational movement that stamps this century as the greatest in human history.

JACQUES COEUR'S HOUSE (BOURGES)

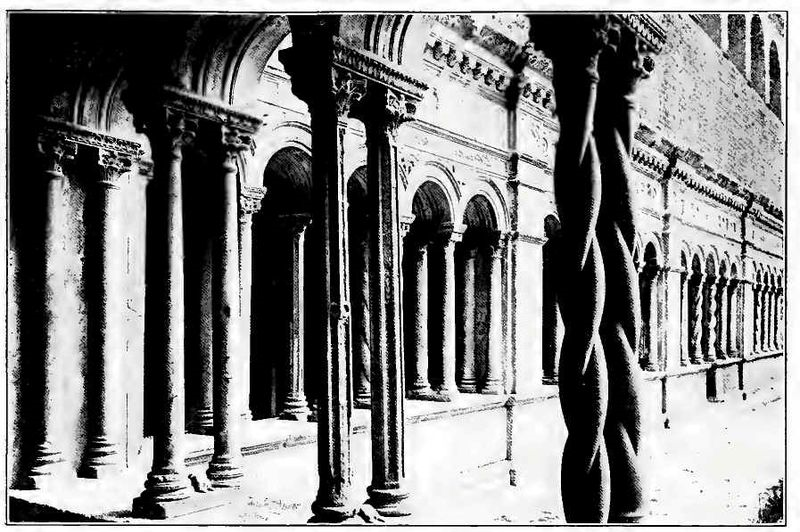

CLOISTER OF ST. JOHN LATERAN (ROME)

III

WHAT AND HOW THEY STUDIED AT THE UNIVERSITIES

It is usually the custom for text books of education to dismiss the teaching at the universities of the Middle Ages with some such expression as: "The teachers were mainly engaged in metaphysical speculations and the students were occupied with exercises in logic and in dialectics, learning in long drawn out disputations how to use the intellectual instruments they possessed but never actually applying them. All knowledge was supposed to be amenable to increase through dialectical discussion and all truth was supposed, to be obtainable as the conclusion of a regular syllogism." Great fun especially is made of the long-winded disputations, the time-taking public exercises in dialectics, the fine hair-drawn distinctions presumably with but the scantiest basis of truth behind them and in general the placing of words for realities in the investigation of truth and the conveyance of information. The sublime ignorance of educators who talk thus about the century that saw the rise of the universities in connection with the erection of the great Cathedrals, is only equaled by their assumption of knowledge.

It is very easy to make fun of a past generation and often rather difficult to enter into and appreciate its spirit. Ridicule comes natural to human nature, alas! but sympathy requires serious mental application for understanding's sake. Fortunately there has come in recent years a very different feeling in the minds of many mature and faithful students of this period, as regards the Middle Ages and its education. Dialectics may seem to be a waste of time to those who consider the training of the human mind as of little value in comparison with the stocking of it with information. Dialectical training will probably not often enable men to earn more money than might have otherwise been the case. This will be eminently true if the dialectician is to devote himself to commercial enterprises in his future life. If he is to take up one of the professions, however, there may be some doubt as to whether even his practical effectiveness will not be increased by a good course of logic. There is, however, another point of view from which this matter of the study of dialectics may be viewed, and which has been taken very well by Prof. Saintsbury of the University of Edinburgh in a recent volume on the Thirteenth Century.

He insists in a passage which we quote at length in the chapter on the Prose of the Century, that if this training in logic had not been obtained at this time in European development, the results might have been serious for our modern languages and modern education. He says: "If at the outset of the career of the modern languages, men had thought with the looseness of modern thought, had indulged in the haphazard slovenliness of modern logic, had popularized theology and vulgarized rhetoric, as we have seen both popularized and vulgarized since, we should indeed have been in evil case." He maintains that "the far-reaching educative influence in mere language, in mere system of arrangement and expression, must be considered as one of the great benefits of Scholasticism." This is, after all, only a similar opinion to that evidently entertained by Mr. John Stuart Mill, who, as Prof. Saintsbury says, was not often a scholastically-minded philosopher, for he quotes in the preface of his logic two very striking opinions from very different sources, the Scotch philosopher, Hamilton, and the French philosophical writer, Condorcet. Hamilton said, "It is to the schoolmen that the vulgar languages are indebted for what precision and analytical subtlety they possess." Condorcet went even further than this, and used expressions that doubless will be a great source of surprise to those who do not realize how much of admiration is always engendered in those who really study the schoolmen seriously and do not take opinions of them from the chance reading of a few scattered passages, or depend for the data of their judgment on some second-hand authority, who thought it clever to abuse these old-time thinkers. Condorcet thought them far in advance of the old Greek philosophers for, he said, "Logic, ethics, and metaphysics itself, owe to scholasticism a precision unknown to the ancients themselves."

With regard to the methods and contents of the teaching in the undergraduate department of the university, that is, in what we would now call the arts department, there is naturally no little interest at the present time. Besides the standards set up and the tests required can scarcely fail to attract attention. Professor Turner, in his History of Philosophy, has summed up much of what we know in this matter in a paragraph so full of information that we quote it in order to give our readers the best possible idea in a compendious form of these details of the old-time education.

"By statutes issued at various times during the Thirteenth Century it was provided that the professor should read, that is expound, the text of certain standard authors in philosophy and theology. In a document published by Denifle, (the distinguished authority on medieval universities) and by him referred to the year 1232, we find the following works among those prescribed for the Faculty of Arts: Logica Vetus (the old Boethian text of a portion of the Organon, probably accompanied by Porphyry's Isagoge); Logica Nova (the new translation of the Organon); Gilbert's Liber Sex Principorium; and Donatus's Barbarismus. A few years later (1255), the following works are prescribed: Aristotle's Physics, Metaphysics, De Anima, De Animalibus, De Caelo et Mundo, Meteorica, the minor psychological treatises and some Arabian or Jewish works, such as the Liber de Causis and De Differentia Spirititus et Animae."

"The first degree for which the student of arts presented himself was that of bachelor. The candidate for this degree, after a preliminary test called responsiones (this regulation went into effect not later than 1275), presented himself for the determination which was a public defense of a certain number of theses against opponents chosen from the audience. At the end of the disputation, the defender summed up, or determined, his conclusions. After determining, the bachelor resumed his studies for the licentiate, assuming also the task of cursorily explaining to junior students some portion of the Organon. The test for the degree of licentiate consisted in a collatio, or exposition of several texts, after the manner of the masters. The student was now a licensed teacher; he did not, however, become magister, or master of arts, until he had delivered what was called the inceptio, or inaugural lecture, and was actually installed (birrettatio). If he continued to teach he was called magisier actu regens; if he departed from the university or took up other work, he was called magister non regens. It may be said that, as a general rule, the course of reading was: (1) for the bachelor's degree, grammar, logic, and psychology; (2) for the licentiate, natural philosophy; (3) for the master's degree, ethics, and the completion of the course of natural philosophy."

Quite apart from the value of its methods, however, scholasticism in certain of its features had a value in the material which it discussed and developed that modern generations only too frequently fail to realize. With regard to this the same distinguished authority whom we quoted with regard to dialectics, Prof. Saintsbury, does not hesitate to use expressions which will seem little short of rankly heretical to those who swear by modern science, and yet may serve to inject some eminently suggestive ideas into a sadly misunderstood subject.

"Yet there has always in generous souls who have some tincture of philosophy, subsisted a curious kind of sympathy and yearning over the work of these generations of mainly disinterested scholars, who, whatever they were, were thorough, and whatever they could not do, could think. And there, have even, in these latter days, been some graceless ones who have asked whether the Science of the nineteenth century, after an equal interval, will be of any more positive value—whether it will not have even less comparative interest than that which appertains to the Scholasticism of the Thirteenth."

In the light of this it has seemed well to try to show in terms of present-day science some of the important reflections with regard to such problems of natural history, as magnetism, the composition of matter, and the relation of things physical to one another, which we now include under the name science, some of the thoughts that these scholars of the Thirteenth Century were thinking and were developing for the benefit of the enthusiastic students who flocked to the universities. We will find in such a review though it must necessarily be brief many more anticipations of modern science than would be thought possible.