полная версия

полная версияThe Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

As a matter of fact, every minutest detail of cathedral construction and ornamentation shared in this artistic triumph. Even the inscriptions, done in brass upon the gravestones that formed part of the cathedral pavements, are models of their kind, and rubbings from them are frequently taken because of their marvelous effectiveness as designs in Gothic tracery.

Their bells were made with such care and such perfection that, down to the present time, nothing better has been accomplished in this handicraft, and their marvelous retention of tone shows how thorough was the work of these early bell-makers.

The triumph of artistic decoration in the cathedrals, however, and the most marvelous page in the book of the Arts of the century, remains to be spoken of in their magnificent stained-glass windows. Where they learned their secret of glass-making we know not. Artists of the modern time, who have spent years in trying to perfect their own work in this line, would give anything to have some of the secrets of the glass-makers of the Thirteenth Century. Such windows as the Five Sisters at York, or the wonderful Jesse window of Chartres with some of its companions, are the despair of the modern artists in stained glass. The fact that their glass-making was not done at one, or even a few, common centers, but was apparently executed in each of these small medieval towns that were the site of a cathedral, only adds to the marvel of how the workmen of the time succeeded so well in accomplishing their purpose of solving the difficult problems of stained glasswork.

PASCHAL CANDLESTICK (BAPTISTERY, FLORENCE)

RELIQUARY (CATHEDRAL ORVIETO, UGOLINO DI VIERI)

If, to crown all that has been said about the Thirteenth Century, we now add a brief account of what was accomplished for men in the matter of liberty and the establishment of legal rights, we shall have a reasonably adequate introduction to this great subject. Liberty is thought to be a word whose true significance is of much more recent origin than the end of the Middle Ages. The rights of men are usually supposed to have received serious acknowledgment only in comparatively recent centuries. The recalling of a few facts, however, will dispel this illusion and show how these men of the later middle age laid the foundation of most of the rights and privileges that we are so proud to consider our birthright in this modern time. The first great fact in the history of modern liberty is the signing of Magna Charta which took place only a little after the middle of the first quarter of the Thirteenth Century. The movement that led up to it had arisen amongst the guildsmen as well as the churchmen and the nobles of the preceding century. When the document was signed, however, these men did not consider that their work was finished. They kept themselves ready to take further advantage of the necessities of their rulers and it was not long before they had secured political as well as legal rights.

Shortly after the middle of the Thirteenth Century the first English parliament met, and in the latter part of that half century it became a formal institution with regularly appointed times of meeting and definite duties and privileges. Then began the era of law in its modern sense for the English people. The English common law took form and its great principles were enunciated practically in the terms in which they are stated down to the present day. Bracton made his famous digest of the English common law for the use of judges and lawyers and it became a standard work of reference. Such it has remained down to our own time. At the end of the century, during the reign of Edward I, the English Justinian, the laws of the land were formulated, lacunae in legislation filled up, rights and privileges fully determined, real-estate laws put on a modern basis, and the most important portions of English law became realities that were to be modified but not essentially changed in all the after time.

This history of liberty and of law-making, so familiar with regard to England, must be repeated almost literally with regard to the continental nations. In France, the foundation of the laws of the kingdom were laid during the reign of Louis IX, and French authorities in the history of law, point with pride, to how deeply and broadly the foundations of French jurisprudence were laid. Under Louis's cousin, Ferdinand III of Castile, who, like the French monarch, has received the title of Saint, because of the uprightness of his character and all that he did for his people, forgetful of himself, the foundations of Spanish law were laid, and it is to that time that Spanish jurists trace the origin of nearly all the rights and privileges of their people. In Germany there is a corresponding story. In Saxony there was the issue of a famous book of laws, which represented all the grants of the sovereigns, and all the claims of subjects that had been admitted by monarchs up to that time. In a word, everywhere there was a codification of laws and a laying of foundations in jurisprudence, upon which the modern superstructure of law was to rise.

This is probably the most surprising part of the Thirteenth Century. When it began men below the rank of nobles were practically slaves. Whatever rights they had were uncertain, liable to frequent violation because of their indefinite character, and any generation might, under the tyranny of some consciousless monarch, have lost even the few privileges they had enjoyed before. At the close of the Thirteenth Century this was no longer possible. The laws had been written down and monarchs were bound by them as well as their subjects. Individual caprice might no longer deprive them arbitrarily of their rights and hard won privileges, though tyranny might still assert itself and a submissive generation might, for a time, allow themselves to be governed by measures beyond the domain of legal justification. Any subsequent generation might, however, begin anew its assertion of its rights from the old-time laws, rather than from the position to which their forbears had been reduced by a tyrant's whim.

Is it any wonder, then, that we should call the generations that gave us the cathedrals, the universities, the great technical schools that were organized by the trades guilds, the great national literatures that lie at the basis of all our modern literature, the beginnings of sculpture and of art carried to such heights that artistic principles were revealed for all time, and, finally, the great men and women of this century—for more than any other it glories in names that were born not to die—is it at all surprising that we should claim for the period which, in addition to all this, saw the foundation of modern law and liberty, the right to be hailed—the greatest of human history?

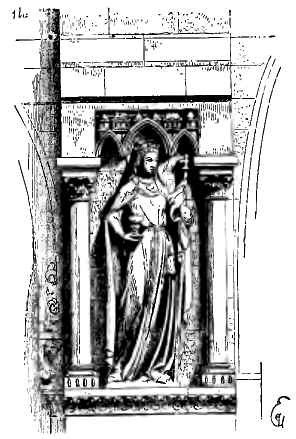

THE CHURCH [SYMBOLIZED] (PARIS)

II

UNIVERSITIES AND PREPARATORY SCHOOLS

To see, at once, how well the Thirteenth deserves the name of the greatest of centuries, it is necessary, only, to open the book of her deeds and read therein what was accomplished during this period for the education of the men of the time. It is, after all, what a generation accomplishes for intellectual development and social uplift that must be counted as its greatest triumph. If life is larger in its opportunities, if men appreciate its significance better, if the development of the human mind has been rendered easier, if that precious thing, whose name, education, has been so much abused, is made readier of attainment, then the generation stamps itself as having written down in its book of deeds, things worthy for all subsequent generations to read. Though anything like proper appreciation of it has come only in very recent times, there is absolutely no period of equal length in the history of mankind in which so much was not only attempted, but successfully accomplished for education, in every sense of the word, as during the Thirteenth Century. This included, not only the education of the classes but also the education of the masses.

For the moment, we shall concern ourselves only with the education offered to, and taken advantage of by so many, in the universities of the time. It was just at the beginning of the Thirteenth Century that the great universities came into being as schools, in which all the ordinary forms of learning were taught. During the Twelfth Century, Bologna had had a famous school of law which attracted students from all over Europe. Under Irnerius, canon and civil law secured a popularity as subjects of study such as they never had before. The study of the old Roman Law brought back with it an interest in the Latin classics, and the beginning of the true new birth—the real renaissance—of modern education must be traced from here. At Paris there was a theological school attached to the cathedral which gradually became noted for its devotion to philosophy as the basis of theology, and, about the middle of the Twelfth Century, attracted students from every part of the civilized world. As was the case at Bologna, interest after a time was not limited to philosophy and theology; other branches of study were admitted to the curriculum and a university in the modern sense came into existence.

During the first quarter of the Thirteenth Century both of these schools developed faculties for the teaching of all the known branches of knowledge. At Bologna faculties of arts, of philosophy and theology, and finally of medicine, were gradually added, and students flocked in ever increasing numbers to take advantage of these additional opportunities. At Paris, the school of medicine was established early in the Thirteenth Century, and there were graduates in medicine before the year 1220. Law came later, but was limited to Canon law to a great extent, Orleans having a monopoly of civil law for more than a century. These two universities, Bologna and Paris, were, in every sense of the word, early in the century, real universities, differing in no essential from our modern institutions that bear the same name.

If the Thirteenth Century had done nothing else but put into shape this great instrument for the training of the human mind, which has maintained its effectiveness during seven centuries, it must be accorded a place among the epoch-making periods of history. With all our advances in modern education we have not found it necessary, or even advisable, to change, in any essential way, this mold in which the human intellect has been cast for all these years. If a man wants knowledge for its own sake, or for some practical purpose in life, then here are the faculties which will enable him to make a good beginning on the road he wishes to travel. If he wants knowledge of the liberal arts, or the consideration of man's duties to himself, to his fellow-man and to his Creator, he will find in the faculties of arts and philosophy and theology the great sources of knowledge in these subjects. If, on the other hand, he wishes to apply his mind either to the disputes of men about property, or to their injustices toward one another and the correction of abuses, then the faculty of law will supply his wants, and finally the medical school enables him, if he wishes, to learn all that can be known at a given time with regard to man's ills and their healing. We have admitted the practical-work subjects into university life, though not without protest, but architecture, engineering, bridge-building and the like, in which the men of the Thirteenth Century accomplished such wonders, were relegated to the guilds whose technical schools, though they did not call them by that name, were quite as effective practical educators as even the most vaunted of our modern university mechanical departments.

It is rather interesting to trace the course of the development of schools in our modern sense of the term, because their evolution recapitulates, to some degree at least, the history of the individual's interest in life. The first school which acquired a European reputation was that of Salernum, a little town not far from Naples, which possessed a famous medical school as early as the ninth century, perhaps earlier. This never became a university, though its reputation as a great medical school was maintained for several centuries. This first educational opportunity to attract a large body of students from all over the world concerned mainly the needs of the body. The next set of interests which man, in the course of evolution develops, has to do with the acquisition and retention of property and the maintenance of his rights as an individual. It is not surprising, then, to find that the next school of world-wide reputation was that of law at Bologna which became the nucleus of a great university. It is only after man has looked out for his bodily needs and his property rights, that he comes to think of his duties toward himself, his fellow-men, and his Creator, and so the third of these great medieval schools, in time, was that of philosophy and theology, at Paris.

It is sometimes thought that the word university applied to these institutions after the aggregation of other faculties, was due to the fact that there was a universality of studies, that all branches of knowledge might be followed in them. The word university, however, was not originally applied to the school itself, which, if it had all the faculties of the modern university, was, in the Thirteenth Century, called a studium generale. The Latin word universitas had quite a different usage at that time. Whenever letters were formally addressed to the combined faculties of a studium generale by reigning sovereigns, or by the Pope, or by other high ecclesiastical authorities, they always began with the designation, Universitas Vestra, implying that the greeting was to all of the faculty, universally and without exception. Gradually, because of this word constantly occurring at the beginning of letters to the faculty, the term universitas came to be applied to the institution.1

While the universities, as is typically exemplified by the histories of Bologna and Paris, and even to a noteworthy degree of Oxford, grew up around the cathedrals, they cannot be considered in any sense the deliberate creation, much less the formal invention, of any particular set of men. The idea of a university was not born into the world in full panoply as Minerva from the brain of Jove. No one set about consciously organizing for the establishment of complete institutions of learning. Like everything destined to mean much in the world the universities were a natural growth from the favoring soil in which living seeds were planted. They sprang from the wonderful inquiring spirit of the time and the marvelous desire for knowledge and for the higher intellectual life that came over the people of Europe during the Thirteenth Century. The school at Paris became famous, and attracted pupils during the Twelfth Century, because of the new-born interest in scholastic philosophy. After the pupils had gathered in large numbers their enthusiasm led to the establishment of further courses of study. The same thing was true at Bologna, where the study of Law first attracted a crowd of earnest students, and then the demand for broader education led to the establishment of other faculties.

Above all, there was no conscious attempt on the part of any supposed better class to stoop down and uplift those presumably below it. As we shall see, the students of the university came mainly from the middle class of the population. They became ardently devoted to their teachers. As in all really educational work, it was the man and not the institution that counted for much. In case of disagreement of one of these with the university authorities, not infrequently there was a sacrifice of personal advantage for the moment on the part of the students in order to follow a favorite teacher. Paris had examples of this several times before the Thirteenth Century, and notably in the case of Abelard had seen thousands of students follow him into the distant desert where he had retired. Later on, when abuses on the part of the authorities of Paris limited the University's privileges, led to the withdrawal of students and the foundation of Oxford, there was a community of interest on the part of certain members of the faculty and thousands of students. This movement was, however, distinctly of a popular character, in the sense that it was not guided by political or other leaders. Nearly all of the features of university life during the Thirteenth Century, emphasize the democracy of feeling of the students, and make it clear that the blowing of the wind of the spirit of human liberty and intellectual enthusiasm influencing the minds of the generation, rather than any formal attempt on the part of any class of men deliberately to provide educational opportunities, is the underlying feature of university foundation and development.

While the great universities of Paris, Bologna, and Oxford were, by far, the most important, they must not be considered as the only educational institutions deserving the name of universities, even in our modern sense, that took definite form during the Thirteenth Century. In Italy, mainly under the fostering care of ecclesiastics, encouraged by such Popes as Innocent III, Gregory IX, and Honorius IV, nearly a dozen other towns and cities saw the rise of Studia Generalia eventually destined, and that within a few decades after their foundation, to have the complete set of faculties, and such a number of teachers and of students as merited for them the name of University.

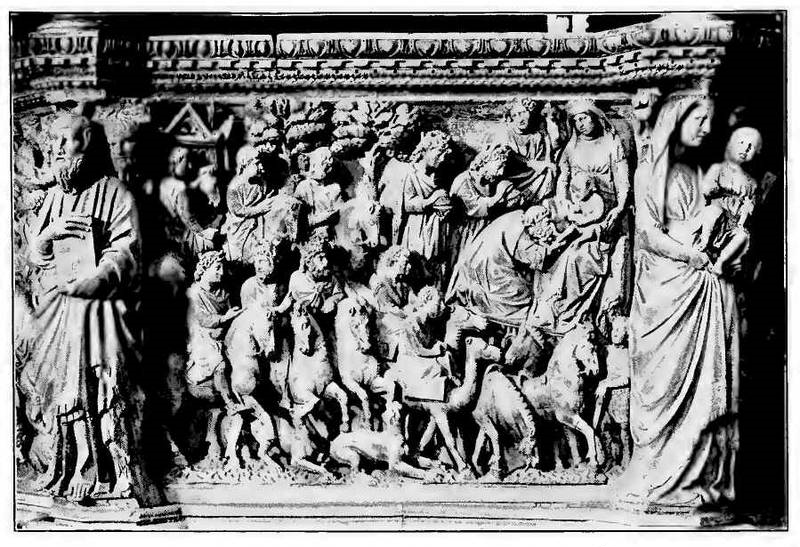

ADORATION OF MAGI (PULPIT, SIENA, NIC. PISANO).

Very early in the century Vicenza, Reggio, and Arezzo became university towns. Before the first quarter of the century was finished there were universities at Padua, at Naples, and at Vercelli. In spite of the troublous times and the great reduction in the population of Rome there was a university founded in connection with the Roman Curia, that is the Papal Court, before the middle of the century, and Siena and Piacenza had founded rival university institutions. Perugia had a famous school which became a complete university early in the Fourteenth Century.

Nor were other countries much behind Italy in this enthusiastic movement. Montpelier had, for over a century before the beginning of the thirteenth, rejoiced in a medical school which was the most important rival of that at Salernum. At the beginning this reflected largely the Moorish element in educational affairs in Europe at this time. During the course of the Thirteenth Century Montpelier developed into a full-fledged university though the medical school still continued to be the most important faculty. Medical students from all over the world flocked to the salubrious town to which patients from all over were attracted, and its teachers and writers of medicine have been famous in medical history ever since. How thorough was the organization of clinical medical work at Montpelier may perhaps best be appreciated from the fact, noted in the chapter on City Hospitals—Organized Charity, that when Pope Innocent III. wished to establish a model hospital at Rome with the idea that it would form an exemplar for other European cities, he sent down to Montpelier and summoned Guy, the head of the Hospital of the Holy Ghost in that city, to the Papal Capital to establish the Roman Hospital of the Holy Ghost and, in connection with it, a large number of hospitals all over Europe.

A corresponding state of affairs to that of Montpelier is to be noted at Orleans, only here the central school, around which the university gradually grouped itself, was the Faculty of Civil Law. Canon law was taught at Paris in connection with the theological course, but there had always been objection to the admission of civil law as a faculty on a basis of equality with the other faculties. There was indeed at this time some rivalry between the civil and the canon law and so the study of civil law was relegated to other universities. Even early in the Twelfth Century Orleans was famous for its school of civil law in which the exposition of the principles of the old Roman law constituted the basis of the university course. During the Thirteenth Century the remaining departments of the university gradually developed, so that by the close of the century, there seem to be conservative claims for over one thousand students. Besides these three, French universities were also established at Angers, at Toulouse, and the beginnings of institutions to become universities early in the next century are recorded at Avignon and Cahors.

Spain felt the impetus of the university movement early in the Thirteenth Century and a university was founded at Palencia about the end of the first decade. This was founded by Alfonso XII. and was greatly encouraged by him. It is sometimes said that this university was transferred to Salamanca about 1230, but this is denied by Denifle, whose authority in matters of university history is unquestionable. It seems not unlikely that Salamanca drew a number of students from Palencia but that the latter continued still to attract many students. About the middle of the Thirteenth Century the university of Valladolid was founded. Before the end of the century a fourth university, that of Lerida, had been established in the Spanish peninsula. Spain was to see the greatest development of universities during the Fourteenth Century. It was not long after the end of the Thirteenth Century before Coimbra, in Portugal, began to assume importance as an educational institution, though it was not to have sufficient faculty and students to deserve the more ambitious title of university for half a century.

While most people who know anything about the history of education realize the important position occupied by the universities during the Thirteenth Century and appreciate the estimation in which they were held and the numbers that attended them, very few seem to know anything of the preparatory schools of the time, and are prone to think that all the educational effort of these generations was exhausted in connection with the university. It is often said, as we shall see, that one reason for the large number of students reported as in attendance at the universities during the Thirteenth Century is to be found in the fact that these institutions practically combined the preparatory school and the academy of our time with the university. The universities are supposed to have been the only centers of education worthy of mention. There is no doubt that a number of quite young students were in attendance at the universities, that is, boys from 12 to 15 who would in our time be only in the preparatory school. We shall explain, however, in the chapter on the Numbers in Attendance at the Universities that students went to college much younger in the past and graduated much earlier than they do in our day, yet apparently, without any injury to the efficacy of their educational training.

In the universities of Southern Europe it is still the custom for boys to graduate with the degree of A. B. at the age of 15 to 16, which supposes attendance at the university, or its equivalent in under-graduate courses, at the age of 12 or even less. There is no need, however, to appeal to the precociousness of the southern nations in explanation of this, since there are some good examples of it in comparatively recent times here in America. Most of the colleges in this country, in the early part of the nineteenth century and the end of the eighteenth, graduated young men of 16 and 17 and thought that they were accomplishing a good purpose, in allowing them to get at their life work in early manhood. Many of the distinguished divines who made names in educational work are famous for their early graduations. Dr. Benjamin Rush, of Philadelphia, whom the medical profession of this country hails as the Father of American Medicine, graduated at Princeton at 15. He must have begun his college course, therefore, about the age of 12. This may be considered inadvisable in our generation, but, it must be remembered that there are many even in our day, who think that our college men are allowed to get at their life-work somewhat too late for their own good.