полная версия

полная версияThe Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

To as great extent as it is possible perhaps for man to secure such a desideratum, the Thirteenth Century workman succeeded in this same purpose. It is for this reason more than even for the magnificent grandeur of the design and the skilful execution with inadequate means, that makes the Gothic Cathedral such a source of admiration and wonder.

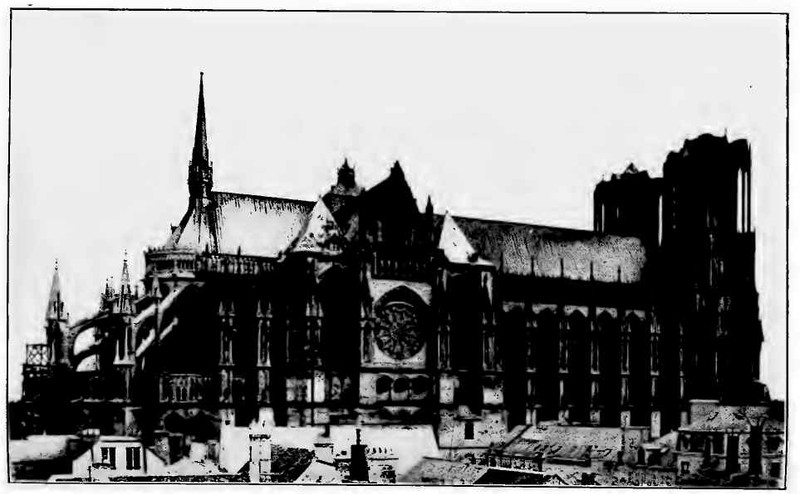

To take first the example of sculpture. It is usually considered that the Thirteenth Century represented a time entirely too early in the history of plastic art for there to have been any fine examples of the sculptor's chisel left us from it. Any such impression, however, will soon be corrected if one but examines carefully the specimens of this form of art in certain Cathedrals. As we have said, probably no more charmingly dignified presentation of the human form divine in stone has ever been made than the figure of Christ above the main door of the cathedral of Amiens, which the Amiennois so lovingly call their "beautiful God." There are some other examples of statuary in the same cathedral that are wonderful specimens of the sculptor's art, lending itself for decorative purposes to architecture. This is true for a number of the Cathedrals. The statues in themselves are not so beautiful, but as portions of a definite piece of structural work such as a doorway or a facade, they are wonderful models of how all the different arts became subservient to the general effect to be produced. It was at Rheims, however, that sculpture reached its acme of accomplishment, and architects have been always unstinted in their praise of this feature of what may be called the Capitol church of France.

Those who have any doubts as to the place of Gothic art itself in art history and who need an authority always to bolster up the opinion that they may hold, will find ample support in the enthusiastic opinion of an authority whom we have quoted already. The most interesting and significant feature of his ardent expression of enthusiasm is his comparison of Romanesque with Gothic art in this respect. The amount of ground covered from one artistic mode to the other is greater than any other advance in art that has ever been made. After all, the real value of the work of the period must be judged, rather by the amount of progress that has been made than by the stage of advance actually reached, since it is development rather than accomplishment that counts in the evolution of the race. On the other hand it will be found that Reinach's opinion of the actual attainments of Gothic art are far beyond anything that used to be thought on the subject a half century ago, and much higher than any but a few of the modern art critics hold in the matter. He says:

"In contrast to this Romanesque art, as yet in bondage to convention, ignorant or disdainful of nature, the mature Gothic art of the Thirteenth Century appeared as a brilliant revival or realism. The great sculptors who adorned the Cathedrals of Paris, Amiens, Rheims, and Chartres with their works, were realists in the highest sense of the word. They sought in Nature not only their knowledge of human forms, and of the draperies that cover them, but also that of the principles of decoration. Save in the gargoyles of cathedrals and in certain minor sculptures, we no longer find in the Thirteenth Century those unreal figures of animals, nor those ornaments, complicated as nightmares, which load the capitals of Romanesque churches; the flora of the country, studied with loving attention, is the sole, or almost the sole source from which decorators take their motives. It is in this charming profusion of flowers and foliage that the genius of Gothic architecture is most freely displayed. One of the most admirable of its creations is the famous Capital of the Vintage in Notre Dame at Rheims, carved about the year 1250. Since the first century of the Roman Empire art had never imitated Nature so perfectly, nor has it ever since done so with a like grace and sentiment."

Reinach defends Gothic Art from another and more serious objection which is constantly urged against it by those who know only certain examples of it, but have not had the advantage of the wide study of the whole field of artistic endeavor in the Thirteenth Century, which this distinguished member of the Institute of France has succeeded in obtaining. It is curious what unfounded opinions have come to be prevalent in art circles because, only too often, writers with regard to the Cathedrals have spent their time mainly in the large cities, or along the principal arteries of travel, and have not realized that some of the smaller towns contained work better fitted to illustrate Gothic Art principles than those on which they depended for their information. If only particular phases of the art of any one time, no matter how important, were to be considered in forming a judgment of it, that judgment would almost surely be unfavorable in many ways because of the lack of completeness of view. This is what has happened unfortunately with regard to Gothic art, but a better spirit is coming in this matter, with the more careful study of periods of art and the return of reverence for the grand old Middle Ages.

CATHEDRAL (RHEIMS)

Reinach says: "There are certain prejudices against this admirable, though incomplete, art which it is difficult to combat. It is often said, for instance, that all Gothic figures are stiff and emaciated. To convince ourselves of the contrary we need only study the marvelous sculpture of the meeting between Abraham and Melchisedech, in Rheims Cathedral; or again in the same Cathedral, the Visitation, the seated Prophet, and the standing Angel, or the exquisite Magdalen of Bordeaux Cathedral. What can we see in these that is stiff, sickly, and puny? The art that has most affinity with perfect Gothic is neither Romanesque nor Byzantine, but the Greek art of from 500 to 450 B. C. By a strange coincidence, the Gothic artists even reproduce the somewhat stereotyped smile of their forerunners." Usually it is said that the Renaissance brought the supreme qualities of Greek plastic art back to life, but here is a thoroughly competent critic who finds them exhibited long before the Fifteenth Century, as a manifestation of what the self-sufficient generations of the Renaissance would have called Gothic, meaning thereby, barbarous art.

What has been said of sculpture, however, can be repeated with even more force perhaps with regard to every detail of construction and decoration. Builders and architects did make mistakes at times, but, even their mistakes always reveal an artist's soul struggling for expression through inadequate media. Many things had to be done experimentally, most things were being done for the first time. Everything had an originality of its own that made its execution something more than merely a secure accomplishment after previous careful tests. In spite of this state of affairs, which might be expected sadly to interfere with artistic execution, the Cathedrals, in the main, are full of admirable details not only worthy of imitation, but that our designers are actually imitating or at least finding eminently suggestive at the present time.

To begin with a well known example of decorative effect which is found in the earliest of the English Cathedrals, that of Lincoln. The nave and choir of this was finished just at the beginning of the Thirteenth Century. The choir is so beautiful in its conception, so wonderful in its construction, so charming in its finish, so satisfactory in all its detail, though there is very little of what would be called striving after effect in it, that it is still called the Angel Choir.

The name was originally given it because it was considered to be so beautiful even during the Thirteenth Century, that visitors could scarcely believe that it was constructed by human hands and so the legend became current that it was the work of angels. If the critics of the Thirteenth Century, who had the opportunity to see work of nearly the same kind being constructed in many parts of England, judged thus highly of it, it is not surprising that modern visitors should be unstinted in their praise. It is interesting to note as representative of the feeling of a cultured modern scientific mind that Dr. Osler said not long ago, in one of his medical addresses, that probably nothing more beautiful had ever come from the hands of man than this Angel Choir at Lincoln. As to who were the designers, who conceived it, or the workmen who executed it, we have no records. It is not unlikely that the famous Hugh of Lincoln, the great Bishop to whom the Cathedral owes its foundation and much of its splendor, was responsible to no little extent for this beautiful feature of his Cathedral church. The workmen who made it were artist-artisans in the best sense of the word and it is not surprising that other beautiful architectural features should have flourished in a country where such workmen could be found.

Almost as impressive as the Angel Choir was the stained glass work at Lincoln. The rose windows are among the most beautiful ever made and one of them is indeed considered a gem of its kind. The beautiful colors and wonderful effectiveness of the stained glass of these old time Cathedrals cannot be appreciated unless the windows themselves are actually seen. At Lincoln there is a very impressive contrast that one can scarcely help calling to attention and that has been very frequently the subject of comment by visitors. During the Parliamentary time, unfortunately, the stained glass at Lincoln fell under the ban of the Puritans. The lower windows were almost completely destroyed by the soldiers of Cromwell's army. Only the rose windows owing to their height were preserved from the destroyer. There was an old sexton at the Cathedral, however, for whom the stained glass had become as the apple of his eye. As boy and man he had lived in its beautiful colors as they broke the light of the rising and the setting sun and they were too precious to be neglected even when lying upon the pavement of the Cathedral in fragments. He gathered the shattered pieces into bags and hid them away in a dark corner of the crypt, saving them at least from the desecration of being trampled to dust.

Long afterwards, indeed almost in our own time, they were found here and were seen to be so beautiful that regardless of the fact that they could not be fitted together in anything like their former places, they were pieced into windows and made to serve their original purpose once more. It so happened that new stained glass windows for the Cathedral of Lincoln were ordered during the Nineteenth Century. These were made at an unfortunate time in stained glass making and are as nearly absolutely unattractive, to say nothing worse, as it is possible to make stained glass. The contrast with the antique windows, fragmentary as they are, made up of the broken pieces of Thirteenth Century glass is most striking. The old time colors are so rich that when the sun shines directly on them they look like jewels. No one pays the slightest attention, unless perhaps the doubtful compliment of a smile be given, to the modern windows which were, however, very costly and the best that could be obtained at that time.

More of the stained glass of the Thirteenth Century is preserved at York where, because of the friendship of General Ireton, the town and the Cathedral were spared the worst ravages of the Parliamentarians. As a consequence York still possesses some of the best of its old time windows. It is probable that there is nothing more beautiful or wonderful in its effectiveness than the glass in the Five Sisters window at York. This is only an ordinary lancet window of five compartments—hence the name—in the west front of the Cathedral. There are no figures on the window, it is only a mass of beautiful greyish green tints which marvelously subdues the western setting sun at the vesper hour and produces the most beautiful effects in the interior of the Cathedral. Here if anywhere one can realize the meaning of the expression dim religious light. In recent years, however, it has become the custom for so many people to rave over the Five Sisters that we are spared the necessity of more than mentioning it. Its tints far from being injured by time have probably been enriched. There can be no doubt at all, however, of the artistic tastes and esthetic genius of the man who designed it. The other windows of the Cathedral were not unworthy of this triumph of art. How truly the Cathedral was a Technical School can be appreciated from the fact that it was able to inspire such workmen to produce these wondrous effects.

Experts in stained glass work have often called attention to the fact that the windows constructed in the Thirteenth Century were not only of greater artistic value but were also more solidly put together. Many of the windows made in the century still maintain their places, in spite of the passage of time, though later windows are sometimes dropping to pieces. It might be thought that this was due to the fact that later stained glass workers were more delicate in the construction of their windows in order not to injure the effect of the stained glass. To some extent this is true, but the stained glass workers of the Thirteenth Century preserve the effectiveness of their artistic pictures in glass, though making the frame work very substantial. This is only another example of their ability to combine the useful with the beautiful so characteristic of the century, stamping practically every phase of its accomplishment and making their work more admirable because its usefulness does not suffer on account of any strained efforts after supposed beauties.

Though it is somewhat out of place here we cannot refrain from pointing out the educational value of this stained glass work.

Some of the stories on these windows gave details of many passages from the Bible, that must have impressed them upon the people much more than any sermon or reading of the text could possibly have accomplished. They were literally sermons in glass that he who walked by had to read whether he would or not. When we remember that the common people in the Middle Ages had no papers to distract them, and no books to turn to for information, such illustrations as were provided by the stained glass windows, by the painting and the statuary decorations of the Cathedrals, must have been studied with fondest devotion even apart from religious sentiment and out of mere inquisitiveness. The famous "prodigal" window at Chartres is a good example of this. Every detail of the story is here pictorially displayed in colors, from the time when the young man demands his patrimony through all the various temptations he met with in being helped to spend it, there being a naive richness of detail in the matter of the temptations that is quite medieval, from the boon companions who first led him astray to the depths of degradation which he finally reached before he returned to his father,—even the picture of the fatted calf is not lacking.

On others of these windows there are the stories of the Patron Saints of certain crafts. The life of St. Crispin the shoemaker is given in rather full detail. The same is true of St. Romain the hunter who was the patron of the furriers. The most ordinary experiences of life are pictured and the methods by which these were turned to account in making the craftsman a saint, must have been in many ways an ideally uplifting example for fellow craftsmen whenever they viewed the window. This sort of teaching could not be without its effect upon the poor. It taught them that there was something else in life besides money getting and that happiness and contentment might be theirs in a chosen occupation and the reward of Heaven at the end of it all, for at the top of these windows the hand of the Almighty is introduced reaching down from Heaven to reward his faithful servants. It is just by such presentation of ideals even to the poor, that the Thirteenth Century differs from the modern time in which even the teaching in the schools seems only to emphasize the fact that men must get money, honestly if they can, but must get money, if they would have what is called success in life.

Another very interesting feature of these windows is the fact that they were usually the gifts of the various Guilds and so represented much more of interest, for the members. It is true that in France, particularly, the monarchs frequently presented stained glass windows and in St. Louis time this was so common that scarcely a French Cathedral was without one or more testimonials of this kind to his generosity; but most of the windows were given by various societies among the people themselves. How much the construction of such a window when it was well done, would make for the education in taste of those who contributed to the expense of its erection, can scarcely be over-estimated. There was besides a friendly rivalry in this matter in the Thirteenth Century, which served to bring out the talents of local artists and by the inevitably suggested comparisons eventually served to educate the taste of the people.

It must not be thought, however, that it was only in stained glass and painting and sculpture—the major arts—that these workmen attained their triumphs. Practically every detail of Cathedral construction is a monument to the artistic genius of the century, to the wonderful inspiration afforded the workmen and to the education provided by the Guilds which really maintained, as we shall see, a kind of Technical School with the approbation and the fostering care of the ecclesiastics connected with the Cathedrals. An excellent example of a very different class of work may be noted in the hinges of the Cloister door of the Cathedral at York. Personally I have seen three art designers sketching these at the same time only one of whom was an Englishman, another coming from the continent and the third from America. The hinge still swings the heavy oak door of the Thirteenth Century. The arborization of the metal as it spreads out from the main shaft of the hinge is beautifully decorative in effect.

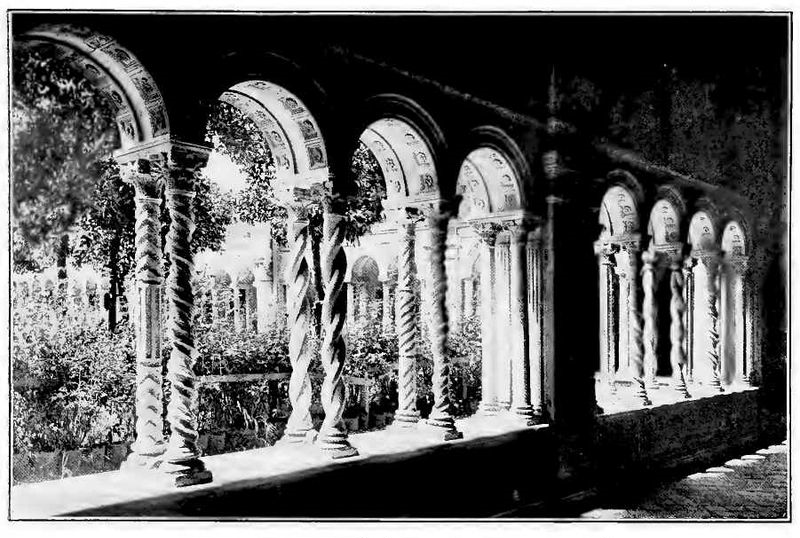

CLOISTER OF ST. PAUL'S (WITHOUT THE WALLS, ROME)

A little study of the hinge seems to show that these branching portions were so arranged as to make the mechanical moment of the swinging door less of a dead weight than it would have been if the hinge were a solid bar of iron. Besides the spreading of the branches over a wide surface serves to hold the woodwork of the door thoroughly in place. While the hinge was beautiful, then it was eminently useful from a good many standpoints, and trivial though it might be considered to be, it was in reality a type of all the work accomplished in connection with these Thirteenth Century Cathedrals. According to the old Latin proverb "omne tulit punctum qui miscuit utile dulci," he scores every point who mingles the useful with the beautiful, and certainly the Thirteenth Century workman succeeded in accomplishing the desideratum to an eminent degree. This mingling of the useful and the beautiful is of itself a supreme difference between the Thirteenth Century generations and our own. Mr. Yeats, the well known Irish poet, in bidding farewell to America some years ago said to a party of friends, that no country could consider itself to be making real progress in culture until the very utensils in the kitchen were beautiful as well as useful. Anything that is merely useful is hideous, and anyone who can handle such things with impunity has not true culture. In the Thirteenth Century they never by any chance made anything that was merely useful, especially not if it was to be associated with their beloved Cathedral.

An excellent example of this can be found in their Chalices and other ceremonial utensils which were meant for Divine Service. As we have said elsewhere The Craftsman, the journal of the Arts and Crafts Movement in this country not long since compared a Chalice of the Thirteenth Century with the prize cups which are offered for yacht races and other competitions in this country. We may say at once that the form which the Chalice received during the Thirteenth Century is that which constitutes to a great extent the model for this sacred vessel ever since and the comparison with the modern design is therefore all the more interesting. In spite of the fact that money is no object as a rule in the construction of many of the modern prize cups, they compare unfavorably according to the writer in The Craftsman with the old time chalices. There is a tendency to over ornamentation which spoils the effectiveness of the lines of the metal work in many cases and there is also only too often, an attempt to introduce forms of plastic art which do not lend themselves well to this class of work. It is in design particularly that the older workman excels his modern colleague though usually there are suggestions from several sources for present day work. In a word the Thirteenth Century Chalice was much more admirable than the modern piece of metal work, because the lines were simpler, the combination of beauty with utility more readily recognizable and the obtrusiveness of the ornamentation much less marked.

This same thing is true for other even coarser forms of metal work in connection with the Cathedrals, and anyone who has seen some of the beautiful iron screens built for Cathedral choirs in the olden times will realize that even the worker in iron must have been an artist as well as a blacksmith. The effect produced, especially in the dim light of the Cathedral, is often that of delicate lace work. To appreciate the strength of the screen one must actually test it with the hands. This of itself represents a very charming adaptation of what might be expected to be rough work meant for protective purposes into a suitable ornament. Some of the gates of the old churchyards are very beautiful in their designs and have often been imitated in quite recent years, for the gates of country places, for our modern millionaires. The Reverend Augustus Jessopp who has written much with regard to the times before the Reformation, says that he has found in his investigations, that not infrequently such gates were made by the village blacksmiths. Most of the old parish records are lost because of the suppression of the parishes as well as the monasteries in Henry the Eighth's time. Some of the original documents are, however, preserved and among them are receipts from the village blacksmith, for what we now admire as specimens of artistic ironwork and corresponding receipts from the village carpenter, for woodwork that we now consider of equally high order. There were carved bench ends and choir stalls which seem to have been produced in this way. Just how these generations of the Thirteenth Century, in little towns of less than ten thousand inhabitants, succeeded in raising up artisans in numbers, capable of doing such fine work, and yet content to make their living at such ordinary occupations, is indeed hard to understand. It must not be forgotten, moreover, that though there was not much furniture during the Thirteenth Century what little there was, was as a rule very carefully and artistically made. Thirteenth Century benches and tables are famous. Cathedrals and castles worked together in inspiring and giving occupation to these wonderful workmen.

It was not only the workmen engaged in the construction of the edifices proper who made the beautiful things and created marvelously artistic treasures during this century. All the adornments of the Cathedrals and especially everything associated in any intimate way with the religious service was sure to be executed with the most delicate taste. The vestments of the time are some of the most beautiful that have ever been made. The historians of needlework tell us that this period represents the most flourishing era of artistic accomplishment with the needle of all modern history. One example of this has secured a large share of notoriety in quite recent years. An American millionaire bought the famous piece of needlework known as the Cope of Ascoli. This is an example of the large garment worn over the shoulders in religious processions and at benediction. The price paid for the garment is said to have been $60,000. This was not considered extortionate or enforced, as the Cope was declared by experts to be one of the finest pieces of needlework in the world. The jewels which originally adorned it had been removed so that the money was paid for the needlework itself. After a time it became clear that the Cope had been stolen before being sold, and accordingly it was returned to the Italian government who presented the American millionaire with a medal for his honesty.