полная версия

полная версияThe Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

This story with regard to the papal prohibition of dissection has no foundation in the history of the times. It has had not a little to do, however, with making these times very much misunderstood and one still continues to see printed references to the misfortune, which is more usually called a crime, that prevented the development of a great humanitarian science because of ecclesiastical prejudice. This story with regard to anatomy, however, is not a whit worse than that which is told of chemistry in almost the same terms. At the beginning of the Fourteenth Century Pope John XXII. is said to have issued a Bull forbidding chemistry under pain of excommunication, which according to some writers in the matter is said to have included the death penalty. It has been felt in the same way as with regard to anatomy, that this was only the culmination of a feeling in ecclesiastical circles against chemistry which must have hampered its progress all during the Thirteenth Century.

An examination of the so-called Bull with regard to chemistry, it is really only a decree, shows even less reason for the slander of Pope John XXII. than of Boniface VIII. John had been scarcely a year on the papal throne when he issued this decree forbidding "alchemies" and inflicting a punishment upon those who practised them. The first sentence of the title of the document is: "Alchemies are here prohibited and those who practise them or procure their being done are punished." This is evidently all of the decree that those who quoted it as a prohibition of chemistry seem ever to have read. Under the name "alchemies," Pope John, as is clear from the rest of the document, meant a particular kind of much-advertised chemical manipulations. He forbade the supposed manufacture of gold and silver. The first sentence of his decree shows how thoroughly he recognized the falsity of the pretensions of the alchemists in this matter. "Poor themselves," he says, "the alchemists promise riches which are not forthcoming." He then forbids them further to impose upon the poor people whose confidence they abuse and whose good money they take to return them only base-metal or none at all.

The only punishment inflicted for the doing of these "alchemies" on those who might transgress the decree was not death or imprisonment, but that the pretended makers of gold and silver should be required to turn into the public treasury as much gold and silver as had been paid them for their alchemies, the money thus paid in to go to the poor. As in the case of the Bull with regard to anatomy, it is very clear that by no possible misunderstanding at the time was the development of the science of chemistry hindered by this papal document. Chemistry had to a certain extent been cultivated at the University of Paris, mainly by ecclesiastics. Both Aquinas and his master Albertus wrote treatises on chemical subjects. Roger Bacon devoted much time to it as is well known, and for the next three centuries the history of chemistry has a number of names of men who were not only unhampered by the ecclesiastical authorities, but who were themselves usually either ecclesiastics, or high in favor with the churchmen of their time and place. This is true of Hollandus, of Arnold of Villanova, of Basil Valentine, and finally of the many abbots and bishops to whom Paracelsus in his time acknowledged his obligations for aid in his chemical studies.

Almost needless to say it has been impossible, in a brief sketch of this kind limited to a single chapter, to give anything like an adequate idea of what the enthusiastic graduate students and professors of the Thirteenth Century succeeded in accomplishing. It is probably this department of University life, however, that has been least understood, or rather we should say most persistently misunderstood. The education of the time is usually supposed to be eminently unpractical, and great advances in the departments of knowledge that had important bearings on human life and its relations were not therefore thought possible. It is just here, however, that sympathetic interpretation and the pointing out of the coordination of intellectual work often considered to be quite distinct from university influences were needed. It is hoped then that this short sketch will prove sufficient to call the attention of modern educators to a field that has been neglected, or at least has received very little cultivation compared to its importance, but which must be sedulously worked, if our generation is to understand with any degree of thoroughness the spirit manifested and the results attained by the medieval universities.

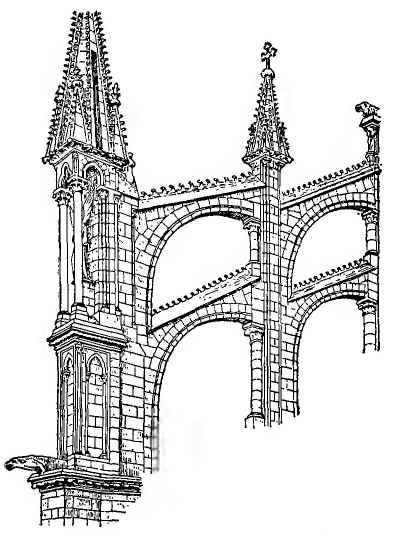

DOUBLE FLYING BUTTRESS (RHEIMS)

VI

THE BOOK OF THE ARTS AND POPULAR EDUCATION

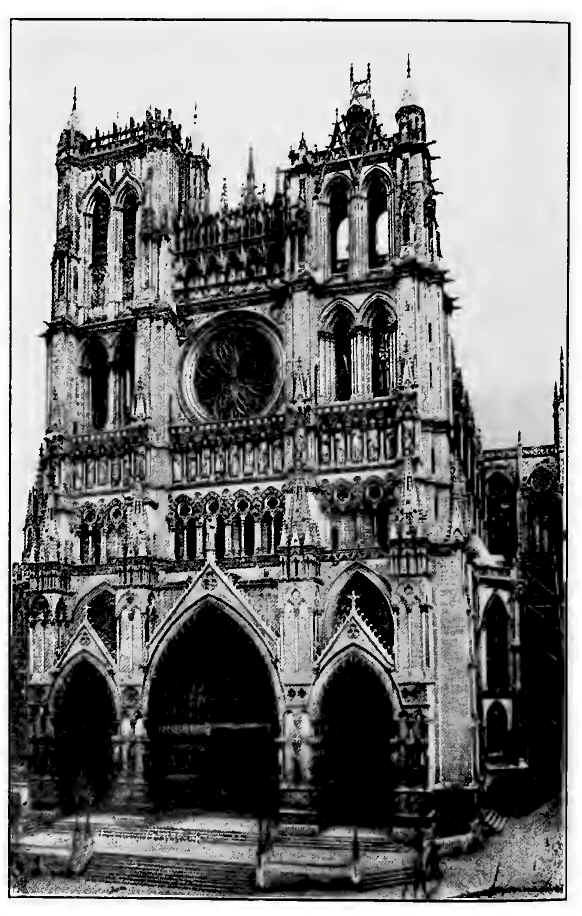

The most important portion of the history of the Thirteenth Century and beyond all doubt the most significant chapter in the book of its arts, is to be found in the great Gothic Cathedrals, so many of which were erected at this time and whose greatest perfection of finish in design and in detail came just at the beginning of this wonderful period. We are not concerned here with the gradual development of Gothic out of the older Romanesque architectural forms, nor with the Oriental elements that may have helped this great evolution. All that especially concerns us is the fact that the generations of the Thirteenth Century took the Gothic ideas in architecture and applied them so marvelously, that thereafter it could be felt that no problem of structural work had been left unsolved and no feature of ornament or decoration left untried or at least unsuggested. The great center of Gothic influence was the North of France, but it spread from here to every country in Europe, and owing to the intimate relations existing between England and France because of the presence of the Normans in both countries, developed almost as rapidly and with as much beauty, and effectiveness as in the mother country.

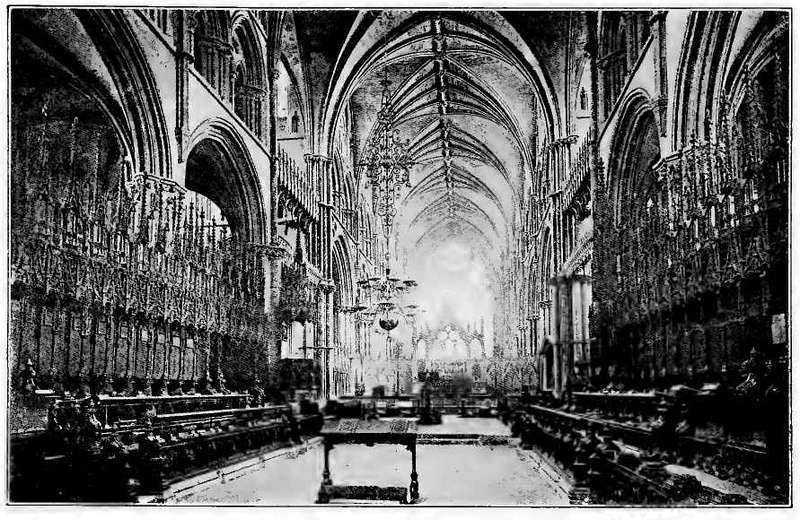

It is in fact in England just before the Thirteenth Century, that the spirit which gave rise to the Cathedrals can be best observed at work and its purposes most thoroughly appreciated. The great Cathedral at Lincoln had some of its most important features before the beginning of the Thirteenth Century and this was doubtless due to the famous St. Hugh of Lincoln, who was a Frenchman by birth and whose experience in Normandy in early life enabled him successfully to set about the creation of a Gothic Cathedral in the country that had become his by adoption.

ANGEL CHOIR (LINCOLN)

Hugh himself was so great of soul, so deeply interested in his people and their welfare, so ready to make every sacrifice for them even to the extent of incurring the enmity of his King (even Froude usually so unsympathetic to medieval men and things has included him among his Short Studies of Great Subjects), that one cannot help but think that when he devoted himself to the erection of the magnificent Cathedral, he realized very well that it would become a center of influence, not only religious but eminently educational, in its effects upon the people of his diocese. The work was begun then with a consciousness of the results to be attained and the influence of the Cathedral must not be looked upon as accidental. He must have appreciated that the creating of a work of beauty in which the people themselves shared, which they looked on as their own property, to which they came nearly every second day during the year for religious services, would be a telling book out of which they would receive more education than could come to them in any other way.

Of course we cannot hope in a short chapter or two to convey any adequate impression of the work that was done in and for the Cathedrals, nor the even more important reactionary influence they had in educating the people. Ferguson says:9

"The subject of the cathedrals, their architecture and decoration is, in fact, practicably inexhaustible. . . . Priests and laymen worked with masons, painters, and sculptors, and all were bent on producing the best possible building, and improving every part and every detail, till the amount of thought and contrivance accumulated in any single structure is almost incomprehensible. If any one man were to devote a lifetime to the study of one of our great cathedrals—assuming it to be complete in all its medieval arrangements—it is questionable whether he would master all its details, and fathom all the reasonings and experiments which led to the glorious result before him. And when we consider that not in the great cities alone, but in every convent and in every parish, thoughtful professional men were trying to excel what had been done and was doing, by their predecessors and their fellows, we shall understand what an amount of thought is built into the walls of our churches, castles, colleges, and dwelling houses. If any one thinks he can master and reproduce all this, he can hardly fail to be mistaken. My own impression is that not one tenth part of it has been reproduced in all the works written on the subject up to this day, and much of it is probably lost and never again to be recovered for the instruction and delight of future ages."

This profound significance and charming quality of the cathedrals is usually unrecognized by those who see them only once or twice, and who, though they are very much interested in them for the moment, have no idea of the wealth of artistic suggestion and of thoughtful design so solicitously yet happily put into them by their builders. People who have seen them many times, however, who have lived in close touch with them, who have been away from them for a time and have come back to them, find the wondrous charm that is in these buildings. Architects and workmen put their very souls into them and they will always be of interest. It is for this reason, that the casual visitor at all times and in all moods finds them ever a source of constantly renewed pleasure, no matter how many times they may be seen.

Elizabeth Robbins Pennell has expressed this power of Cathedrals to please at all times, even after they have been often seen and are very well known, in a recent number of the Century, in describing the great Cathedral of Notre Dame, "Often as I have seen Notre Dame," she says, "the marvel of it never grows less. I go to Paris with no thought of time for it, busy about many other things and then on my way over one of the bridges across the river perhaps, I see it again on its island, the beautiful towers high above the houses and palaces and the view now so familiar strikes me afresh with all the wonder of my first impression."

This is we think the experience of everyone who has the opportunity to see much of Notre Dame. The present writer during the course of his medical studies spent many months in daily view of the Cathedral and did a good deal of work at the old Morgue, situated behind the Cathedral. Even at the end of his stay he was constantly finding new beauties in the grand old structure and learning to appreciate it more and more as the changing seasons of a Paris fall and winter and spring, threw varying lights and shadows over it. It was like a work of nature, never growing old, but constantly displaying some new phase of beauty to the passers-by. Mrs. Pennell resents only the restorations that have been made. Generations down even to our time have considered that they could rebuild as beautifully as the Thirteenth Century constructors; some of them even have thought that they could do better, doubtless, yet their work has in the opinion of good critics served only to spoil or at least to detract from the finer beauty of the original plan. No wonder that R. M. Stevenson, who knew and loved the old Cathedral so well, said: "Notre Dame is the only un-Greek thing that unites majesty, elegance, and awfulness." Inasmuch as it does so it is a typical product of this wonderful Thirteenth Century, the only serious rival the Greeks have ever had. But of course it does not stand alone. There are other Cathedrals built at the same time at least as handsome and as full of suggestions. Indeed in the opinion of many critics it is inferior in certain respects to some three or four of the greatest Gothic Cathedrals.

It cannot be possible that these generations builded so much better than they knew, that it is only by a sort of happy accident that their edifices still continue to be the subject of such profound admiration, and such endless sources of pleasure after seven centuries of experience. If so we would certainly be glad to have some such happy accident occur in our generation, for we are building nothing at the present time with regard to which we have any such high hopes. Of course the generations of Cathedral builders knew and appreciated their own work. The triumph of the Thirteenth Century is therefore all the more marked and must be considered as directly due to the environment and the education of its people. We have then in the study of their Cathedrals the keynote for the modern appreciation of the character and the development of their builders.

It will be readily understood, how inevitably fragmentary must be our consideration of the Cathedrals, yet there is the consolation that they are the best known feature of Thirteenth Century achievement and that consequently all that will be necessary will be to point out the significance of their construction as the basis of the great movement of education and uplift in the century. Perhaps first a word is needed with regard to the varieties of Gothic in the different countries of Europe and what they meant in the period.

Probably, the most interesting feature of the history of Gothic architecture, at this period, is to be found in the circumstance that, while all of the countries erected Gothic structures along the general lines which had been laid down by its great inventors in the North and Center of France, none of the architects and builders of the century, in other countries, slavishly followed the French models. English Gothic is quite distinct from its French ancestor, and while it has defects it has beauties, that are all its own, and a simplicity and grandeur, well suited to the more rugged character of the people among whom it developed. Italian Gothic has less merits, perhaps, than any of the other forms of the art that developed in the different nations. In Italy, with its bright sunlight, there was less crying need for the window space, for the provision of which, in the darker northern countries, Gothic was invented, but, even here the possibilities of decorated architecture along certain lines were exhausted more fully than anywhere else, as might have been expected from the esthetic spirit of the Italians. German Gothic has less refinement than any of the other national forms, yet it is not lacking in a certain straightforward strength and simplicity of appearance, which recommends it. The Germans often violated the French canons of architecture, yet did not spoil the ultimate effect. St. Stephen's in Vienna has many defects, yet as a good architectural authority has declared it is the work of a poet, and looks it.

A recent paragraph with regard to Spanish Gothic in an article on Spain, by Havelock Ellis, illustrates the national qualities of this style very well. As much less is generally known about the special development of Gothic architecture in the Spanish peninsula, it has seemed worth while to quote it at some length:

"Moreover, there is no type of architecture which so admirably embodies the romantic spirit as Spanish Gothic. Such a statement implies no heresy against the supremacy of French Gothic. But the very qualities of harmony and balance of finely tempered reason, which make French Gothic so exquisitely satisfying, softened the combination of mysteriously grandiose splendor with detailed realism, in which lies the essence of Gothic as the manifestation of the romantic spirit. Spanish Gothic at once by its massiveness and extravagance and by its realistic naturalness, far more potently embodies the spirit of medieval life. It is less esthetically beautiful but it is more romantic. In Leon Cathedral, Spain possesses one of the very noblest and purest examples of French Gothic—a church which may almost be said to be the supreme type of the Gothic ideal, of a delicate house of glass finely poised between buttresses; but there is nothing Spanish about it. For the typical Gothic of Spain we must go to Toledo and Burgos, to Tarragona and Barcelona. Here we find the elements of stupendous size, of mysterious gloom, of grotesque and yet realistic energy, which are the dominant characters, alike of Spanish architecture and of medieval romance."

Those who think that the Gothic architecture came to a perfection all its own by a sort of wonderful manifestation of genius in a single generation, and then stayed there, are sadly mistaken. There was a constant development to be noted all during the Thirteenth Century. This development was always in the line of true improvement, while just after the century closed degeneration began, decoration became too important a consideration, parts were over-loaded with ornament, and the decadence of taste in Gothic architecture cannot escape the eye even of the most untutored. All during the Thirteenth Century the tendency was always to greater lightness and elegance. One is apt to think of these immense structures as manifestations of the power of man to overcome great engineering difficulties and to solve immense structural problems, rather than as representing opportunities for the expression of what was most beautiful and poetic in the intellectual aspirations of the generations. But this is what they were, and their architects were poets, for in the best sense of the etymology of the word they were creators. That their raw material was stone and mortar rather than words was only an accident of their environment. Each of the architects succeeded in expressing himself with wonderful individuality in his own work in each Cathedral.

The improvements introduced by the Thirteenth Century people into the architecture that came to them, were all of a very practical kind, and were never suggested for the sake of merely adding to opportunities for ornamentation. In this matter, skillful combinations of line and form were thought out and executed with wonderful success. At the beginning of the century, delicate shafts of marble, highly polished, were employed rather freely, but as these seldom carried weight, and were mainly ornamental in character, they were gradually eliminated, yet, without sacrificing any of the beauty of structure since combinations of light and shade were secured by the composition of various forms, and the use of delicately rounded mouldings alternated with hollows, so as to produce forcible effects in high light and deep shadow. In a word, these architects and builders, of the Thirteenth Century, set themselves the problem of building effectively, making every portion count in the building itself, and yet, securing ornamental effects out of actual structure such as no other set of architects have ever been able to surpass, and, probably, only the Greek architects of the Periclean period ever equaled. Needless to say, this is the very acme of success in architectural work, and it is for this reason that the generations of the after time have all gone back so lovingly to study the work of this period.

It might be thought, that while Gothic architecture was a great invention in its time and extremely suitable for ecclesiastical or even educational edifices of various kinds, its time of usefulness has passed and that men's widening experience in structural work, ever since, has carried him far away from it. As a matter of fact, most of our ecclesiastical buildings are still built on purely Gothic lines, and a definite effort is made, as a rule, to have the completed religious edifice combine a number of the best features of Thirteenth Century Gothic. With what success this has been accomplished can best be appreciated from the fact, that none of the modern structures attract anything like the attention of the old, and the Cathedrals of this early time still continue to be the best asset of the towns in which they are situated, because of the number of visitors they attract. Far from considering Gothic architecture outlived, architects still apply themselves to it with devotion because of the practical suggestions which it contains, and there are those of wide experience, who still continue to think it the most wonderful example of architectural development that has ever come, and even do not hesitate to foretell a great future for it.

Reinach, in his Story of Art Throughout the Ages,10 has been so enthusiastic in this matter that a paragraph of his opinion must find a place here. Reinach, it may be said, is an excellent authority, a member of the Institute of France, who has made special studies in comparative architecture, and has written works that carry more weight than almost any others of our generation:

"If the aim of architecture, considered as an art, should be to free itself as much as possible from subjection to its materials, it may be said that no buildings have more successfully realized this ideal than the Gothic churches. And there is more to be said in this connection. Its light and airy system of construction, the freedom and slenderness of its supporting skeleton, afford, as it were, a presage of an art that began to develop in the Nineteenth Century, that of metallic architecture. With the help of metal, and of cement reinforced by metal bars, the moderns might equal the most daring feats of the Gothic architects. It would even be easy for them to surpass them, without endangering the solidity of the structure, as did the audacities of Gothic art. In the conflicts that obtain between the two elements of construction, solidity and open space, everything seems to show that the principle of free spaces will prevail, that the palaces and houses of the future will be flooded with air and light, that the formula popularized by Gothic architecture has a great future before it, and that following the revival of the Graeco-Roman style from the Sixteenth Century, to our own day, we shall see a yet more enduring renaissance of the Gothic style applied to novel materials."

It would be a mistake, however, to think that the Gothic Cathedrals were impressive only because of their grandeur and immense size. It would be still more a mistake to consider them only as examples of a great development in architecture. They are much more than this; they are the compendious expression of the art impulses of a glorious century. Every single detail of the Gothic Cathedrals is not only worthy of study but deserving of admiration, if not for itself, then always for the inadequate means by which it was secured, and most of these details have been found worthy of imitation by subsequent generations. It is only by considering the separate details of the art work of these Cathedrals that the full lesson of what these wonderful people accomplished can be learned. There have been many centuries since, in which they would be entirely unappreciated. Fortunately, our own time has come back to a recognition of the greatness of the art impulse that was at work, perfecting even what might be considered trivial portions of the cathedrals, and the brightest hope for the future of our own accomplishment is founded on this belated appreciation of old-time work.

It has been said that the medieval workman was a lively symbol of the Creator Himself, in the way in which he did his work. It mattered not how obscure the portion of the cathedral at which he was set, he decorated it as beautifully as he knew how, without a thought that his work would be appreciated only by the very few that might see it. Trivial details were finished with the perfection of important parts. Microscopic studies in recent years have revealed beautiful designs on pollen grains and diatoms which are far beneath the possibilities of human vision, and have only been discovered by lens combinations of very high powers of the compound microscope. Always these beauties have been there though hidden away from any eye. It was as if the Creator's hand could not touch anything without leaving it beautiful as well as useful.

CATHEDRAL (AMIENS)