полная версия

полная версияPlain English

Cultivate also this trait yourself. Do not accept a thing simply because some one says it is so. Insist upon knowing for yourself. This is the secret of progress, that we should think for ourselves, investigate for ourselves and not fear to face the facts of life or to express our own ideas. The wise man does not accept a thing because it is old nor does he reject it because it is new. He inquires, demands, reasons and satisfies himself as to the merit of the question. So the Interrogation Point in the written language of man has a tremendous meaning. It stands for the open and inquiring mind; for the courage that dares question all things and seek the truth.

THE INTERROGATION POINT

523. An Interrogation Point should be placed after every direct question.

A direct question is one that can be answered. An indirect question is one that cannot be answered. If I say, Why do you not study?, I am asking a direct question to which you can give an answer; but if I say, I wonder why you do not study, I have asked an indirect question which does not require a direct answer.

Why do you not go? (Direct)

He asked why you did not go. (Indirect)

524. When an interrogative clause is repeated in the body of another sentence, use the interrogation point after the clause, and begin the clause with a capital letter. For example:

The question, Shall we be involved in war?, should be settled by the people.

THE EXCLAMATION POINT

525. The exclamation point should be placed after words, phrases or sentences that express strong emotion. For example:

Oh! When shall peace reign again?

Alas! I am undone!

To the firing line! the battle rages!

526. Ordinarily the exclamation point is placed immediately after the interjection or word used as an interjection, but frequently when the strong emotion continues throughout the expression, the exclamation point is placed at the close of the sentence instead of after the interjection, even though the interjection comes first in the sentence. For example:

On, Comrades, on!

Charge, Chester, charge!

THE DASH

527. The dash is a much abused punctuation mark. A great many writers who are not familiar with the rules of punctuation use a dash whenever they feel the need of some sort of a punctuation mark. Their rule seems to be, "whenever you pause make a dash." Punctuation marks indicate pauses but a dash should not be used upon every occasion. The dash should not be used as a substitute for the comma, semi-colon, colon, etc. In reality, the dash should be used only when these marks cannot be correctly used.

528. The chief use of the dash is to indicate a sudden break in the thought or a sudden change in the construction of the sentence. For example:

In the next place—but I cannot discuss the matter further under the circumstances.

529. The dash is frequently used to set a parenthetical expression off from the rest of the sentence when it has not as close connection with the sentence as would be indicated by commas. As for example:

The contention may be true—although I do not believe it—that this sort of training is necessary.

530. The dash is also used in place of commas to denote a longer or more expressive pause. For example:

The man sank—then rose—then sank again.

531. The dash is often used after an enumeration of several items as a summing up. For example:

Production, distribution, consumption—all are a part of economics.

532. A dash is often used when a word or phrase is repeated for emphasis. For example:

Is there universal education—education for every child beneath the flag? It is not for the masses of the children—not for the children of the masses.

533. If the parenthetical statements within dashes require punctuation marks, this mark should be placed before the second dash. For example:

War for defense—and was there ever a war that was not for defense?—was permitted by the International.

This sight—what a wonderful sight it was!—greeted our eyes with the dawn.

534. The dash is also used to indicate the omission of a word, especially such words as as, namely, viz., etc. For example:

Society is divided into two classes—the exploited and the exploiting classes.

535. After a quotation, use the dash before the name of the author. For example:

Life only avails, not the having lived.—Emerson.

536. The dash is used to mark the omission of letters or figures. For example:

It happened in the city of M—.

It was in the year 18—.

PARENTHESIS

537. In our study of the comma and the dash we have found that parenthetical statements are set off from the rest of the sentence sometimes by a comma and sometimes by a dash. When the connection with the rest of the sentence is close, and yet the words are thrown in in a parenthetical way, commas are used to separate the parenthetical statement from the rest of the sentence.

538. When the connection is not quite so close, the dash is used instead of the comma to indicate the fact that this statement is thrown in by way of explanation or additional statement. But when we use explanatory words or parenthetical statements that have little or no connection with the rest of the sentence, these phrases or clauses are separated from the rest of the sentences by the parenthesis.

539. GENERAL RULE:—Marks of parenthesis are used to set off expressions that have no vital connection with the rest of the sentence. For example:

Ignorance (and why should we hesitate to acknowledge it?) keeps us enslaved.

Education (and this is a point that needs continual emphasis) is the foundation of all progress.

THE PUNCTUATION OF THE PARENTHESIS

540. If the parenthetical statement asks a question or voices an exclamation, it should be followed by the interrogation point or the exclamation point, within the parenthesis. For example:

We are all of us (who can deny it?) partial to our own failings.

The lecturer (and what a marvelous orator he is!) held the audience spellbound for hours.

OTHER USES OF THE PARENTHESIS

541. An Interrogation Point is oftentimes placed within a parenthesis in the body of a sentence to express doubt or uncertainty as to the accuracy of our statement. For example:

In 1858 (?) this great movement was started.

John (?) Smith was the next witness.

542. The parenthesis is used to include numerals or letters in the enumeration of particulars. For example:

Economics deals with (1) production, (2) distribution, (3) consumption.

There are three sub-heads; (a) grammar, (b) rhetoric, (c) composition.

543. Marks of parenthesis are used to inclose an amount or number written in figures when it is also written in words, as:

We will need forty (40) machines in addition to those we now have.

Enclosed find Forty Dollars ($40.00) to apply on account.

THE BRACKET

544. The bracket [ ] indicates that the word or words included in the bracket are not in the original discourse.

545. The bracket is generally used by editors in supplying missing words, dates and the like, and for corrections, additions and explanations. For example:

This rule usually applies though there are some exceptions. [See Note 3, Rule 1, Page 67].

546. All interpretations, notes, corrections and explanations, which introduce words or phrases not used by the author himself, should be enclosed in brackets.

547. Brackets are also used for a parenthesis within a parenthesis. If we wish to introduce a parenthetical statement within a parenthetical statement this should be enclosed in a bracket. For example:

He admits that this fact (the same fact which the previous witness [Mr. James E. Smith] had denied) was only partially true.

QUOTATION MARKS

548. Quotation marks are used to show that the words enclosed by them are the exact words of the writer or speaker.

549. A direct quotation is always enclosed in quotation marks. For example:

He remarked, "I believe it to be true."

But an indirect quotation is not enclosed in quotation marks. For example:

He remarked that he believed it was true.

550. When the name of an author is given at the close of a quotation it is not necessary to use the quotation marks. For example:

All courage comes from braving the unequal.—Eugene F. Ware.

When the name of the author precedes the quotation, the marks are used, as in the following:

It was Eugene F. Ware who said, "Men are not great except they do and dare."

551. When we are referring to titles of books, magazines or newspapers, or words and phrases used in illustration, we enclose them in quotation marks, unless they are written in italics. For example:

"Whitman's Leaves of Grass" or Whitman's Leaves of Grass. "The New York Call" or The New York Call. The word "book" is a noun, or, The word book is a noun.

THE QUOTATION WITHIN A QUOTATION

552. When a quotation is contained within another, the included quotation should be enclosed by single quotation marks and the entire quotation enclosed by the usual marks. For example:

He began by saying, "The last words of Ferrer, 'Long live the modern school' might serve as the text for this lecture."

The speaker replied, "It was Karl Marx who said, 'Government always belongs to those who control the wealth of the country.'"

You will note in this sentence that the quotation within the quotation occurs at the end of the sentence so there are three apostrophes used after it, the single apostrophe to indicate the included quotation and the double apostrophe which follows the entire quotation.

PUNCTUATION WITH QUOTATION MARKS

553. Marks of punctuation are (except the interrogation point and the exclamation point which are explained later) placed inside the quotation marks. For example:

A wise man said, "Know thyself."

Notice that the period is placed after the word thyself and is followed by the quotation marks.

"We can easily rout the enemy," declared the speaker.

Notice that the comma is placed after enemy, and before the quotation marks.

554. The Interrogation Point and the Exclamation Point are placed within the quotation marks if they refer only to the words quoted, but if they belong to the entire sentence they should be placed outside the quotation marks. For example:

He said, "Will you come now?"

Did he say, "Will you come now"?

He said, "What a beautiful night!"

How wonderfully inspiring is Walt Whitman's poem, "The Song of the Open Road"!

555. Sometimes parenthetical or explanatory words are inserted within a quotation. These words should be set off by commas, and both parts of the quotation enclosed in quotation marks. For example:

"I am aware," he said, "that you do not agree with me."

"But why," the speaker was asked, "should you make such a statement?"

"I do not believe," he replied, "that you have understood me."

THE APOSTROPHE

556. The apostrophe is used to indicate the omission of letters or syllables, as: He doesn't, instead of does not; We're, instead of we are; I'm, instead of I am; it's, instead of it is; ne'er, instead of never; they'll, instead of they will, etc.

557. The apostrophe is also used to denote possession. In the single form of the nouns it precedes the s. In the plural form of nouns ending in s it follows the s. For example:

Boy's, man's, girl's, king's, friend's, etc.

Boys', men's, girls', kings', friends', etc.

Note that the apostrophe is not used with the possessive pronouns ours, yours, its, theirs, hers.

558. The apostrophe is used to indicate the plural of letters, figures or signs. For example:

Dot your i's and cross your t's.

He seems unable to learn the table of 8's and 9's.

Do not make your n's and u's so much alike.

559. The apostrophe is used to mark the omission of the century in dates, as: '87 instead of 1887, '15 instead of 1915.

THE HYPHEN

560. The hyphen is used between the parts of a compound word or at the end of a line to indicate that a word is divided. We have so many compound words in our language which we have used so often that we have almost forgotten that they were compound words so it is not always easy to decide whether the hyphen belongs in a word or not. As, for example; we find such words as schoolhouse, bookkeeper, railway and many others which are, in reality, compound words and in the beginning were written with the hyphen. We have used them so frequently and their use as compound words has become so commonplace, that we no longer use the hyphen in writing them. Yet frequently you will find them written with the hyphen by some careful writer.

561. As a general rule the parts of all words which are made by uniting two or more words into one should be joined by hyphens, as:

Men-of-war, knee-deep, half-hearted, full-grown, mother-in-law, etc.

562. The numerals expressing a compound number should be united by a hyphen, as; forty-two, twenty-seven, thirty-nine, etc.

563. When the word self is used with an adverb, a noun or an adjective, it is always connected by the hyphen, as; self-confidence, self-confident, self-confidently, self-command, self-assertive, self-asserting, etc.

564. When the word fold is added to a number of more than one syllable, the hyphen is always used, as; thirty-fold, forty-fold, fifty-fold, etc. If the numeral has but one syllable, do not use the hyphen, as; twofold, threefold, fourfold, etc.

565. When fractions are written in words instead of figures always use the hyphen, as; one-half, one-fourth, three-sevenths, nine-twelfths, etc.

566. The words half and quarter, when used with any word, should be connected by a hyphen, as; half-dollar, quarter-pound, half-skilled, half-barbaric, half-civilized, half-dead, half-spent, etc.

567. Sometimes we coin a phrase for temporary use in which the words are connected by the hyphen. For example:

It was a never-to-be-forgotten day.

He wore a sort of I-told-you-so air.

They were fresh-from-the-pen copies.

ADDITIONAL MARKS OF PUNCTUATION

There are a few other marks of punctuation which we do not often use in writing but which we find on the printed page. It is well for us to know the meaning of these marks.

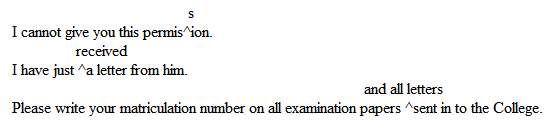

568. The caret (^) is used to mark the omission of a letter or word or a number of words. The omitted part is generally written above, and the caret shows where it should be inserted. For example:

The above examples illustrate the use of the caret with the omission of a letter, a word or phrase.

569. If a letter or manuscript is not too long, it should always be rewritten and the omissions properly inserted. Occasionally, however, we are in a hurry and our time is too limited to rewrite an entire letter because of the omission of a single letter or word so we can insert it by the use of the caret. If, however, there are many mistakes, the letter or paper should be rewritten, for the too frequent use of the caret indicates carelessness in writing and does not produce a favorable impression upon the recipient of your letter or manuscript.

MARKS OF ELLIPSIS

570. Sometimes a long dash (–) or succession of asterisks (* * * * * *) or of points (. . . . . .) is used to indicate the omission of a portion of a sentence or a discourse. In printed matter usually the asterisks are used to indicate an omission. In typewritten matter usually a succession of points is used to indicate an omission. In writing, these are difficult to make and the omission of the portion of material is usually indicated by a succession of short dashes (– — – —).

MARKS OF REFERENCE

571. On the printed page you will often find the asterisk (*), or the dagger, (†), the section (§), or parallel lines (||), used to call your attention to some note or remark written at the close of the paragraph or on the margin, at the bottom of the page or the end of the chapter. It is advisable to hunt these up as soon as you come to the mark which indicates their presence, for they usually contain some matter which explains or adds to the meaning of the sentence which you have just finished reading.

Exercise 1

In the following exercise, note the various marks of punctuation and determine why each one is used:

THE MARSEILLAISEYe sons of toil, awake to glory!Hark, hark, what myriads bid you rise;Your children, wives and grandsires hoary—Behold their tears and hear their cries!Shall hateful tyrants, mischief breeding,With hireling hosts, a ruffian band,—Affright and desolate the land,While peace and liberty lie bleeding?CHORUSTo arms! to arms! ye brave!Th' avenging sword unsheathe!March on, march on, all hearts resolvedOn Victory or Death.With luxury and pride surrounded,The vile, insatiate despots dare,Their thirst for gold and power unbounded,To mete and vend the light and air;Like beasts of burden would they load us,Like gods would bid their slaves adore,But Man is Man, and who is more?Then shall they longer lash and goad us?(CHORUS)O Liberty! can man resign thee,Once having felt thy generous flame?Can dungeons' bolts and bars confine thee,Or whip thy noble spirit tame?Too long the world has wept bewailing,That Falsehood's dagger tyrants wield;But Freedom is our sword and shield,And all their arts are unavailing!(CHORUS)—Rouget de Lisle.THUS SPAKE ZARATHUSTRAI teach ye the Over-man. The man is something who shall be overcome. What have ye done to overcome him?

All being before this made something beyond itself: and you will be the ebb of this great flood, and rather go back to the beast than overcome the man?

What is the ape to the man? A mockery or a painful shame. And even so shall man be to the Over-man: a mockery or a painful shame.

Man is a cord, tied between Beast and Over-man—a cord above an abyss.

A perilous arriving, a perilous traveling, a perilous looking backward, a perilous trembling and standing still.

What is great in man is that he is a bridge, and no goal; what can be loved in man is that he is a going-over and a going-under.

I love them that know how to live, be it even as those going under, for such are those going across.

I love them that are great in scorn, because these are they that are great in reverence, and arrows of longing toward the other shore!—Nietzsche.

SPELLING

LESSON 30

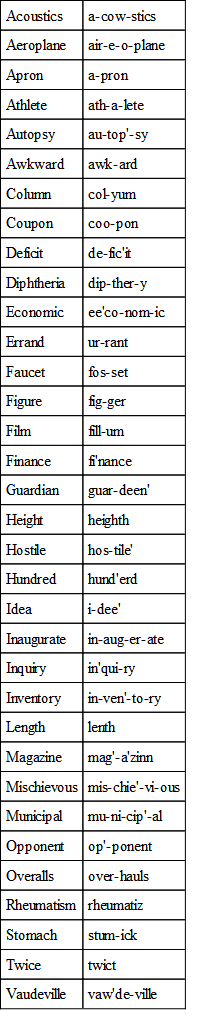

There are a great many words in English which are frequently mispronounced; the accent is placed upon the wrong syllable; for example, thea'ter instead of the'ater; the wrong sound is given to the vowel, for example, hearth is pronounced hurth. Sometimes, too, an extra letter is added in the pronunciation; for example, once is often pronounced as though it were spelled wunst.

The following is a list of common words that are frequently mispronounced, and there are many others which you may add to this list as they occur to you. Look up the correct pronunciation in the dictionary and pronounce them many times aloud.

In the second column in this list is given the incorrect pronunciation, which we often hear.

There are a number of words in English which sound very much alike and which we are apt to confuse. For example, I heard a man recently say in a speech that the party to which he belonged had taken slow poison and now needed an anecdote. It is presumed that he meant that it needed an antidote. Some one else remarked that a certain individual had not been expelled but simply expended. He undoubtedly meant that the individual had been suspended.

This confusion in the use of words detracts from the influence which our statements would otherwise have. There are a number of words which are so nearly alike that it is very easy to be confused in the use of them. In our spelling lesson for this week we have a number of the most common of these easily confounded words. Add to the list as many others as you can.

Monday

Lightening, to make light

Lightning, an electric flash

Prophesy, to foretell

Prophecy, a prediction

Accept, to take

Except, to leave out

Tuesday

Advice, counsel

Advise, to give counsel

Attendants, servants

Attendance, those present

Stationary, fixed

Stationery, pens, paper, etc.

Wednesday

Formerly, in the past

Formally, in a formal way

Addition, process of adding

Edition, publication

Celery, a vegetable

Salary, wages

Thursday

Series, a succession

Serious, solemn

Precedent, an example

President, chief or head

Partition, a division

Petition, a request

Friday

Ingenious, skillful

Ingenuous, honest

Jester, one who jests

Gesture, action

Lose, to suffer loss

Loose, to untie

Saturday

Presence, nearness

Presents, gifts

Veracity, truthfulness

Voracity, greediness

Disease, illness

Decease, death

THE END AND THE BEGINNING

As we look back over the study of these thirty lessons we find that we have covered quite a little ground. We have covered the entire field of English grammar including punctuation. But our study of English must not conclude with the study of this course. This is simply the foundation which we have laid for future work. You know when students graduate from high school or college the graduation is called the Commencement. That is a peculiarly fitting term, for the gaining of knowledge ought truly to be the commencement of life for us.

Some one has said that the pursuit of knowledge might be compared to a man's marriage to a charming, wealthy woman. He pursued and married her because of her wealth but after marriage found her so charming that he grew to love her for herself. So we ofttimes pursue wisdom for practical reasons because we expect it to serve us in the matter of making a living; because we expect it to make us more efficient workers; to increase our efficiency to such an extent that we may command a higher salary, enter a better profession and be more certain of a job.