полная версия

полная версияHow to Catalogue a Library

I think that Mr. Bradshaw's argument is convincing against making any arbitrary rule of this kind, and affixing a definite size to every variety of form-designation. But at the same time we must remember that the form-notation has very largely been used for a size-notation, and that bibliographers alone cannot make this change, because publishers, booksellers, and bookbinders all use the notation as well as cataloguers. After all I cannot help thinking that the difficulty has been very greatly exaggerated. Folio and quarto are almost entirely used as terms of form-notation, and they are usually found sufficient except in the case of atlas or elephant folios, which seem to require some distinguishing designation. Nowadays a large number of library books are in what is called demy octavo. This I would distinguish as octavo, and all below that size I would call small octavos, and all above large octavos. Very few modern books are styled duodecimos; therefore that form will not give the cataloguer much trouble. It is clearly useless for the latter to distinguish books by such meaningless terms as foolscap octavo, post octavo, etc., like the publisher. Of course there is the difference in size between old and new books. The ordinary octavo of the old books is a smaller size than the modern octavo, but this will be settled by the date, and among the old books there will be no difficulty in finding duodecimos.

Mr. Nicholson has entered very fully into this question of size-notation in his Bodleian Rules, where he gives two tables as guides for correct description. Rule 57 is: "The size of a book printed on water-marked paper is to be described in accordance with Table I., on unwater-marked paper with Table II."

CollationIn most catalogues the note of the size will finish the entry, but it is a very useful addition when the number of pages of all books in single volumes is given. Sometimes the pages of the book itself only are noted without reference to the preliminary matter, and sometimes the Roman numerals are added on to the Arabic numerals and given as one total; but this latter practice is not to be commended. The best plan is to set down the pages thus—pp. xv, 421 (some put this pp. xv + 421, but the plus sign is not necessary); or if the preliminary matter is not paged, thus—half-title, title, five preliminary leaves, pp. 467.

In the case of very rare and valuable works, a full collation becomes necessary, and such collation should be drawn up according to the plan accepted among bibliographers, which can be seen in the standard bibliographies of early printed books, and such a model bibliography as Upcott's Bibliographical Account of the Principal Works relating to English Topography (3 vols., 8vo, 1818).

Even when it is not thought necessary to give a collation, it will be well to notice if a book contains a portrait, or plates.

CHAPTER V.

REFERENCES AND SUBJECT INDEX

I suppose it may be conceded that in the abstract the most useful kind of catalogue is that which contains the titles and subject references in one alphabet; but in the particular case of a large library this system is not so convenient, because the subject references unnecessarily swell the size of the catalogue, and by their frequency confuse the title entries. For instance, it is something appalling to conjecture what would be the size of the British Museum Catalogue if subject references were included in the general alphabet. In the case of a large library it will be more convenient to have an index of subjects forming a separate alphabet by itself, and this cannot be made until the catalogue of authors is completed. Taking a somewhat arbitrary limit, it may be said that in libraries containing more than ten thousand volumes it will be found more useful to have a distinct index of subjects, while in catalogues of libraries below that number it will generally be advisable to include the subject references with the titles in one general alphabet.

If all the subject references are reserved for an index, there will still remain a large number of references in the general alphabet which are required for the proper use of the catalogue; and here it may be well to say something as to the nomenclature of references. Mr. Cutter, in the valuable series of definitions prefixed to his Rules for a Dictionary Catalogue, has the following:—

"Reference, partial registry of a book (omitting the imprint) under author, title, subject, or kind, referring to a more full entry under some other heading; occasionally used to denote merely entries without imprints, in which the reference is implied. The distinction of entry and reference is almost without meaning for Short, as a title-a-liner saves nothing by referring unless there are several references.

"Analytical reference, or simply an analytical registry of some part of a book or of some work contained in a collection, referring to the heading under which the book or collection is entered.

"Cross reference, reference from one subject to another.

"Heading reference, from one form of a heading to another.

"First-word reference, catch-word reference, subject-word reference, same as first-word entry, omitting the imprint and referring."

These definitions are important, and it would be well if the distinction here made as to what a cross-reference really is were borne in mind. It has become the practice among bibliographers to describe all references as cross-references. This is the case in the British Museum rules:—

"LV. Cross-references to be divided into three classes, from name to name, from name to work, and from work to work. Those of the first class to contain merely the name, title, or office of the person referred to as entered; those of the second, so much of the title referred to besides as, together with the size and date, may give the means of at once identifying, under its heading, the book referred to; those of the third class to contain moreover so much of the title referred from, as may be necessary to ascertain the object of the reference."

The public often cause a still further confusion in words, for they cry out for the shelf-marks to be placed to references. If this be done, they no longer remain references, but become double entries.

There are many disadvantages in this plan of putting press-marks to references, but it is adopted at the British Museum, and it certainly is annoying to have to run from one end of a many-volumed catalogue to another.

In Mr. Nichols's Handbook for Readers it is said (p. 42) that "a work is never entered at full length more than once and it is only from the main entry that the book-ticket must be made out." But if the press-marks are added to the references, one would imagine that they are intended to be used, and it is scarcely to be expected that any one will take the trouble to refer to another place when he has sufficient information under his eyes.

Catalogue work is different from index work, where the entries may be duplicated without inconvenience; but in the case of books, if all the references have press-marks, there is considerable danger of confusion whenever the position of a book is changed. The main entries will be corrected, but some of the references will almost certainly be overlooked. If the books are never moved, there is no great harm in putting press-marks to the references.

It must, I think, be conceded that when the references are so long as they often are in the British Museum Catalogue, and as seems to be contemplated by Mr. Cutter's remark quoted above, they are really duplicate or subsidiary entries rather than references.

There is no real necessity to copy any part of the titles in the great majority of references. Take, for instance, the following two modes of referring from the subject of a biography to the authors:—

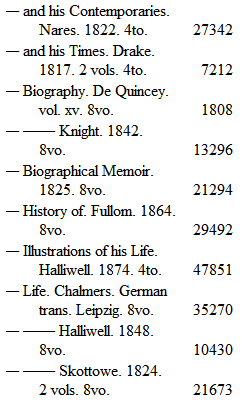

Shakespeare:

These entries are taken from a large heading, and do not come together as they do here. By following the wording of the title in this way you do not get a true index. For instance, under this same main heading of Shakespeare we have in different parts of the sub-alphabet:—

All these books are on the plots, and should come together. At present anyone looking at the entry would suppose that there was only one book on the plots of the plays in the library.

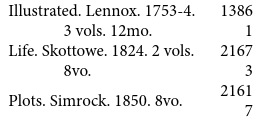

Another way of making the references may be set out thus:—

Shakespeare:

Life: Chalmers, De Quincey, Fullom

(1864), Halliwell (1848), Knight

(1842), Skottowe (1824).

—– S. and his Contemporaries: Nares

(1822).

—– S. and his Times: Drake (1817).

Plots of his Plays: Lennox (1753),

Simrock (1850), Skottowe (1824).

Not only does the second plan take up less space, but it is also the more convenient, as giving the required information in the clearest manner.

All references should be in English,29 and the subject of the book should be used for the reference rather than the often periphrastic form of the title. Thus, in making a subject reference for the following book:—

Mudie (Robert). The Feathered Tribes of the British Islands. 1834. 2 vols.

—the reference must be from "Birds" or "Ornithology," as it will be useless to refer from "Feathered Tribes."

No reference should be made to a title which does not indicate the information sought for. Thus, if a work contains an account of some subject which is not specified on the title, this must not be referred to unless a note is added to the title to show that the book does contain this information. Sometimes one reference will be sufficient for a group of titles. Thus, in referring from one form of an author's name to another, it is not necessary to repeat the titles under that author's name even in the shortest manner.

It is not well in subject references included in an alphabetical catalogue or in an alphabetical index of subjects to classify at all. Thus Gold should be under G, and Silver under S; and at the end of the heading of Metals or Metallurgy such cross-references as these can be added: "See also Gold, Silver."

It is not easy to calculate the average number of references to a given number of chief entries. If we exclude subject references, it may be roughly put at about a third. If subject references are included, it will be about two to one, or twice as many references as titles. Many titles will only require one reference, but others will help to turn the balance,—as, for instance, the following, which will require ten references:—

The Life of Haydn, in a Series of Letters written at Vienna [originally written in Italian by G. Carpani], followed by the Life of Mozart [by A. H. F. von Slichtegroll], with Observations on Metastasio, and on the Present State of Music in France and Italy. Translated from the French of L. A. C. Bombet, with Notes by the Author of the Sacred Melodies [W. Gardiner]. London, 1817. 8vo.

In the first place, Bombet is a pseudonym for Henri Beyle; therefore, according to the rule adopted in the catalogue, there must be a different reference. If the title is placed under Beyle, then there must be a reference from Bombet; and if under the pseudonym, there must be a reference from Beyle. There must be references from Haydn, Mozart, and Metastasio, from Slichtegroll, Carpani, and Gardiner, from Music, and possibly from France and Italy.

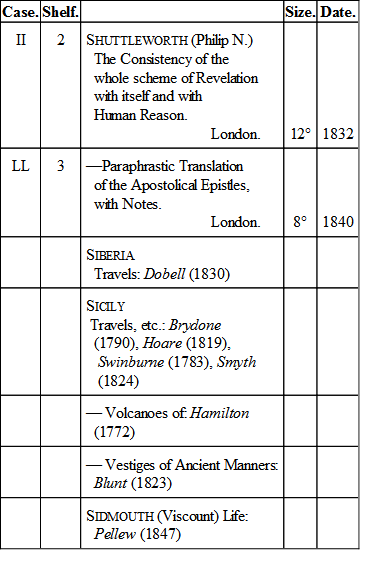

The specimen page here given will show how a subject index may be incorporated in one alphabet with an author's catalogue:—

It will be noticed that in the case of references the word see is omitted. If the names to be referred to, which follow a colon, are printed in italic, or, in the case of a manuscript catalogue, are underscored with red ink, they will be clearly distinguishable without the word see, and a wearisome repetition will be avoided. In the case of cross-references at the end to some other heading [see also], it will be more convenient to use the word than to omit it.

Panizzi was an advocate for a Subject Index, or "Index of Matters," as he called it,30 but he did not venture to recommend such a work officially to the trustees.31 He was fully examined on this subject before the Commission in 1849, and he referred to a memorandum which he had submitted to the Council of the Royal Society when employed upon their catalogue. He there writes:—

"A catalogue of a library is intended principally to give an accurate inventory of the books which it comprises; and is in general consulted either to ascertain whether a particular book is in the collection, or to find what works it contains on a given subject. To obtain these ends, classed catalogues have been compiled, in which the works are systematically arranged according to their subjects. Many distinguished individuals in different countries have drawn up catalogues of this description, but no two of them have agreed on the same plan of classification; and even those who have confessedly followed the system of another person have fancied it necessary to depart in some particulars from their model.... Those who want either to consult a book, of which they only know the subject, or to find what books on a particular subject are in the library, can obtain this information (as far as it can be collected from a title-page, which is all that can be expected in a catalogue) more easily from an index of matters to an alphabetical catalogue than by any other means. Here also nothing is left to discretion as far as concerns order. Entries, being short cross-references, are in a great measure avoided; and repetitions, far from being inconvenient, will save the time and trouble of looking in more places than one in order to find what is wanted.... The plan which is proposed was adopted by Dr. Watt in his Bibliotheca Britannica, the usefulness of which work must be acknowledged by every one conversant with bibliography. That it would not be so useful had any systematical arrangement been followed seems undeniable. The vast plan of the Bibliotheca Britannica, however, did not allow its author to give, either to the titles of the books or to the index, that extent which ought to be given to both in the Catalogue of the Library of the Royal Society" (Minutes of Evidence, p. 704).

Although here Panizzi makes the sound remark that the information to be expected in a catalogue is that which is found in the title-page, he had previously expressed a considerably more comprehensive opinion. He wrote:—

"The catalogue of a library like that of the Royal Society should be as complete as possible; that is, it should give all the information requisite concerning any book which may be the object of inquiry. Whether a work be printed separately, or in a collection—whether it extend to the greater part of a folio volume, or occupy only part of a single leaf—no distinction should be made; the title of each should be separately entered. Hence every one of the Memoirs or papers in the acts of academies; every one of the articles in scientific journals or collections, whatever they may be, should have its separate place in the catalogue. Thus, for instance, all the letters in Hanschius' Collection should be entered in their proper places under the writers' names. It is only by carrying this principle to the fullest extent that a catalogue can be called complete, and a library, more particularly of books relating to science, made as useful as it is capable of being. This, however, would make a great difference in the expense, and take considerable time."

A little consideration will show that such an extensive principle of action could not be practically carried out, and we may well ask whether it would be advisable to adopt such a plan even if it could be carried out. We regret the waste of labour spent in cataloguing the same book over and over again, but how much greater would be the waste of labour and money if the managers of every library which contained the Philosophical Magazine thought it necessary to include the whole contents of that periodical in its catalogue! The labour of cataloguing these series is the work of bibliographers, and such valuable books of reference as the Royal Society Catalogue of Scientific Papers and Poole's Index of Periodical Literature are suitable for all libraries.

To return to the mode of carrying out a subject index, it may be again remarked that it is not necessary to follow the titles textually, and if the titles are so followed there can be no advantage in making the references longer than in Watt's Bibliotheca. In primary entries the titles must be accurately followed, but in references it is often much more convenient to dispense with the wording chosen by the author. Two books with totally different titles are often identical in subject, and the indexer saves the time of the consulter by realizing this fact and acting upon it.

I think that any one who compares the system adopted in the indexes to the Catalogues of the Library of the Athenæum Club and of the London Library with that of, say, the Catalogue of the Manchester Free Library, 1881, will at once see how much more readily the former can be used.

Mr. Parry, in his answer 7351 (Minutes, p. 470), advocates the plan of having a separate index of subjects, and in spite of all that has been said in favour of dictionary catalogues, I hold that this is the simplest and most useful for students; although for popular libraries there is much to be said in favour of dictionary catalogues. One of the most elaborate indexes I know is that by my brother, Mr. B. R. Wheatley, for the Catalogue of the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society. By this plan he who knows what he wants finds it without being confused by, to him, useless references, while he who does not know can consult the index.

In an index the headings will of course be in alphabet, and the sub-headings may be so also; but often some system of classification will be better. No hard-and-fast rule can be made for all cases. But it is usually better to bring the subjects of the books together, regardless of the wording of the title.

CHAPTER VI.

ARRANGEMENT

Rule II. of the British Museum is: "Titles to be arranged alphabetically, according to the English alphabet only (whatever be the order of the alphabet in which a foreign name might have been entered in its original language);" and this rule has been generally followed. Mr. Cutter (rule 169) adds to this, "Treat I and J, U and V, as separate letters;" and every consulter of the British Museum Catalogue must wish that this rule was adopted there, for anything so confusing as this unnecessary mixing of the letters I and J and U and V it is scarcely possible to imagine. Mr. Cutter goes on: "ij, at least in the olden Dutch names, should be arranged as y; do not put Spanish names beginning with Ch, Ll, Ñ, after all other names beginning with C, L, and N, as is done by the Spanish Academy."

The Museum rule (XIII.) is: "German names in which the letters ä, ö, or ü occur, to be spelt with the diphthong æ, œ, and ue respectively."

Mr. Cutter follows this, and adds to it (rule 25):—

"In Danish names, if the type å is not to be had, use its older equivalent aa; in a manuscript catalogue the modern orthography ä should be employed. Whatever is chosen should be uniformly used, however the names may appear in the books. The diphthong æ should not be written ae, nor should ö be written oe; ö, not oe, should be used for ø.

"In Hungarian names write ö, ü, with the diæresis (not oe, ue), and arrange like the English o, u.

"The Swedish names, ä, å, ö, should be so written (not ae, oe), and arranged as the English a, o."

The Cambridge rule (10) is as follows: "German and Scandinavian names, in which the forms ä, ö, ü, å, occur, to be treated, for the purpose of alphabetical sequence, as if spelt with ae, oe, and ao respectively. In German names ä, ö, ü, to be printed ae, oe, ue."

The Library Association rule (44) is: "The German ä, ö, ü, are to be arranged as if written out in full ae, oe, ue."

The first part of the Cambridge rule and the whole of that of the Library Association is likely to lead to confusion. The only safe way to deal with these letters is either to spell them out, or to arrange them as if they were English letters. The English alphabet must be pre-eminent in an English catalogue.

The rule that M', Mc, St., etc., should be arranged as if spelt Mac, Saint, etc., stands on a different basis from the above, and the reason is, as stated by Mr. Cutter (rule 173), "because they are so pronounced." When we see St., we at once say Saint, and therefore look under Sa.

The Index Society rule enters fully into this point, and explains what is a difficulty to some: "6. Proper names with the prefix St., as St. Albans, St. John, to be arranged in the alphabet as if written in full, Saint. When the word Saint represents a ceremonial title, as in the case of St. Alban, St. Giles, and St. Augustine, these names to be arranged under the letters A and G respectively; but the places St. Albans, St. Giles, and St. Augustine will be found under the prefix Saint. The prefixes M' and Mc to be arranged as if written in full, Mac."

When several titles follow one heading, it is necessary to use a dash in place of repeating the heading, and there are one or two points worthy of attention in respect to this dash.

The Library Association rule is: "35. The heading is not to be repeated; a single indent or dash indicates the omission of the preceding heading or title."

The Index Society rule is rather fuller: "17. A dash, instead of an indentation, to be used as a mark of repetition. The dash to be kept for entries exactly similar, and the word to be repeated when the second differs in any way from the first. The proper name to be repeated when that of a different person. In the case of joint authors the Christian names or initials of the first, whose surname is arranged in the alphabet, to be in parentheses, but the Christian names of the second to be in the natural order, as Smith (John) and Alexander Brown, not Smith (John) and Brown (Alexander)."

The reason for the last direction is that the Christian name is only brought back in order to make the alphabetical position of the surname clear; and as this is not necessary in respect to the second person, the names should remain in their natural order.

Dashes should be of a uniform length, and that length should not be too great. It is a great mistake to suppose that the dash is to be the length of the line which is not repeated. If it is necessary to mark the repetition of a portion of the title as well as the author, this should be indicated by another dash, and not by the elongation of the former one; thus:—

Milton (John), Works in Verse and Prose, Printed from the Original Editions, with Life by the Rev. John Mitford. 8 vols. 8vo. London, 1851.

—– Poetical Works, with Notes, Life, etc., by the Rev. H. J. Todd. 6 vols. 8vo. London, 1801.

–– – – Second Edition. 7 vols. royal 8vo. London, 1809.

–– – with Notes, edited by Sir Egerton Brydges. 6 vols. small 8vo. London, 1853.

All the dashes except the first, which represents the author's name, can be got rid of by using the words [the same] or [another edition], etc.

In the alphabetization of a catalogue the prefixes in personal names, even when printed separately, are to be treated as if they were joined; thus:—

De Montfort.

Demophilus.

De Morgan.

Demosthenes.

De Quincey.

Des Barres.

Du Chaillu.

In the case of compound words a different plan, however, is to be adopted. Each word is to be treated as separate, and arranged accordingly. The Index Society rule is as follows: "4. Headings consisting of two or more distinct words are not to be treated as integral portions of one word; thus the arrangement should be:—