полная версия

полная версияSpanish and Portuguese South America during the Colonial Period; Vol. 2

1806.

Whilst thus in the lower Platine provinces all was preparation for the struggle which every one foresaw, in England bright hopes were built on the capture of the South-American city whose loss was not yet known. Sir David Baird, who was still at the Cape of Good Hope, received orders to reinforce Beresford with fourteen hundred men; and on the 11th of October, 1806, a squadron, commanded by Admiral Sterling, and carrying four thousand three hundred and fifty soldiers, under the orders of Sir Samuel Auchmuty, set sail for the Plata. On the 12th of November, another expedition of four thousand three hundred and ninety-one men, under the command of General Crawford, set out for Chili. The fourteen hundred men from the Cape of Good Hope reached the River Plate after the surrender of Beresford, and when Admiral Popham had realized that it was of no use to think of retaking that town. Even Monte Video was by this time so well prepared that it was impossible for him to reduce that place with the insufficient forces at his disposal. He therefore thought fit to land at Maldonado, a small harbour on the left side of the river, where he disembarked his men, and awaited an addition to his strength.

No sooner was the defeat of Beresford known in England than the ministry despatched a fast vessel from Portsmouth with orders to General Crawford to join Sir Samuel Auchmuty; whilst, shortly afterwards, a third body, consisting of sixteen hundred and thirty picked troops, set out under the orders of Lieutenant-General John Whitelocke, who was to assume the command-in-chief of the united English forces in La Plata, whose number would amount to twelve thousand men, supported by a fleet of eighteen men-of-war, together with eighty transports.

1807.

General Auchmuty was the first to arrive. Taking with him the fourteen hundred men whom Popham had landed at Maldonado, and likewise three hundred men from the fleet, he invested Monte Video on the 28th of January. He was attacked by Sobremonte, with some mounted militia, but who were quickly dispersed, and who retired to Colonia. Auchmuty then established his batteries, and commenced to bombard Monte Video from the south. On the 2d of February the breach was declared practicable, and at daylight on the 3d the general ordered an assault.

An English writer, who as a youth was present at the assault on Monte Video, gives a vivid picture of the scene. Arriving with high hopes in the river Plata, in December 1806, the author of “Letters on Paraguay,” and his fellow-travellers, learned to their dismay that Buenos Ayres had been retaken by the Spaniards, and that General Beresford and his army were prisoners. Sir Samuel Auchmuty was now investing Monte Video, and, with the exception of the country immediately around that town, there was no footing for Englishmen in Spanish America. The “Enterprise” was ordered to proceed to the roadstead, there, together with hundreds of other ships similarly situated, to be under the orders of the English admiral.

Monte Video was strongly and regularly fortified. Its harbour presented a scene of the greatest animation; brigs-of-war were running close under the walls, and bombarding the citadel from the sea, whilst thousands of spectators on board ship were tracing, in breathless suspense, the impression made by every shell upon the town, and by every ball upon the breach. The frequent sorties made by the Spanish troops, and the repulses which they sustained, were watched with painful interest.

At length, one morning before dawn, the breach was enveloped in one mighty spread of conflagration. The roar of cannon was incessant, and the atmosphere was one dense mass of smoke, impregnated with the smell of gunpowder. By the aid of the night-glass, and by the flashes from the guns, it might be seen that a deadly struggle was going forward on the walls. It was succeeded by an awful pause; and presently the dawn of day revealed the British ensign floating from the battlements. The sight was received by a shout of triumph from the fleet.

That day the travellers might land, and might view the scene of the terrible carnage which had ensued. The grenadier company of the 40th regiment, missing the breach, had been annihilated. Colonel Vassall, of the 38th regiment, had been the first to mount, and whilst waving his sword had fallen, shot through the heart. The breach had been barricaded again and again with piles of tallow in skins, and with bullocks’ hides, which as they gave way carried the assailants with them on to the points of the enemy’s bayonets. The carnage on both sides was dreadful and was long uninterrupted; and piles of wounded, or of dead and dying, were to be seen on every side, whilst sufferers were being conveyed on litters to the hospitals and churches.

This writer bears the highest testimony to the discipline of the British troops as well as to the energy and philanthropy of their general, owing to which a speedy stop was put to the scenes of pillage which invariably accompany the capture of a fortified city. But to those who have witnessed the terrible effects produced by a bombardment, it is astonishing how quickly its results may be made to disappear, and such was now the case at Monte Video. In a week or two, says Mr. Robertson, the more prominent ravages of war disappeared, and in a month after the capture the inhabitants were getting as much confidence in their invaders as could possibly be expected. This early confidence was mainly attributable to the mild and equitable government of the commander-in-chief, Sir Samuel Auchmuty, who permitted the civil institutions of the country to remain unchanged, and who showed the greatest affability to all classes. The hundreds of vessels in the harbour now discharged their human freight, who were able somehow to procure accommodation on shore; and Monte Video soon began to have the appearance of being an English town, since to its mixed population of Spaniards, Creoles, and Mulattoes were added some four thousand English soldiers, together with two thousand merchants, traders, and adventurers of the same nation.

The loss of the Spaniards in the assault had been seven hundred men. The garrison, together with its commander General Huïdobro, became prisoners, six hundred of whom were despatched to England. The news of the capture of Monte Video produced such commotion in Buenos Ayres, that the people who could not yet readily believe that they were not invincible, chose to impute the blame to Sobremonte. He was accordingly solemnly deposed by a popular vote, the chief authority being vested in the High Court of Justice, pending the receipt of orders from Spain, whither Sobremonte was sent. Thus the province of Buenos Ayres was in full course of revolution. It was the people who had taken the lead in every movement which had followed the attack on Beresford; but as they were acting against the enemies of the King of Spain, everything was done in the name of that monarch, even to the degradation and dismissal of his Viceroy. The High Court of Justice, to which was temporarily confided the executive power, was composed exclusively of Spaniards. The magistrates, though they did not fail to perceive the revolutionary tendency of events, were yet aware that the Creoles alone were in a position to withstand the English; they therefore yielded to the current. The leaders of the revolutionary party took advantage of the complaisance of the Spanish authorities; and the municipality, who were greatly influenced by popular meetings, assumed every day greater importance.

On the capture of Monte Video the English established themselves in that most desirable place in a manner which showed that they had every intention of retaining possession of it. Whilst General Auchmuty occupied the chief city and likewise Maldonado, Colonel Pack had driven the Spaniards from Colonia, and the side of the river Plata, which to-day belongs to the Republic of Uruguay, was then in full English possession. Already the merchant ships thronged the river-side, carrying more goods than the people could afford to buy. In Monte Video goods were sold at a hundred per cent. less than the prices which, owing to Custom-House exactions, they had hitherto commanded. Even a half-English, half-Spanish journal, called the “The Southern Star,” was set on foot under English auspices, with a view of proclaiming the downfall of Spain.

General Whitelocke did not reach the Plata until three months after the capture of Monte Video. He was promptly joined by General Crawford, who had been overtaken on the Atlantic by the despatch-boat sent after him. With the united force at his disposal the reconquest of Buenos Ayres and its territory seemed to the commander-in-chief, as to everybody else, a very simple affair, as indeed it was. It was impossible to conceive that where a force of sixteen hundred men had in the first instance succeeded, one of ten thousand of the same army should fail. The reason, however, is not far to seek. It lay in the difference between Beresford and Whitelocke.

The English force was divided into four brigades. The first, composed of a battalion of rifles and one of infantry of the line, was commanded by General Crawford; the second, composed of three battalions, was led by Sir Samuel Auchmuty; the third, of two battalions and a regiment of dismounted dragoons, was under General Lumley; the fourth, likewise of two battalions and a regiment of dismounted dragoons, was under Colonel Mahon. The mounted batteries were kept in reserve, under the immediate orders of the commander-in-chief. The entire effective force amounted to nearly ten thousand men, some two thousand having been left for the defence of Monte Video, together with a small body of militia composed of all the English residents.

The expedition set out amidst the cheers of the fleet, and on Sunday, the 28th of June, the troops disembarked at the small port of Enseñada, forty-eight miles south of Buenos Ayres. Why a spot so distant from the city should have been selected it is not easy to imagine; but this was in accordance with all the subsequent proceedings of the general. Their landing was unopposed by the Spaniards, who, of course, anticipated that it would be effected nearer the town, probably at Quilmes, where Beresford had set foot. Without loss of time the advanced guard, under General Levison Gower, the second in command, was en route, and it was followed by the main body of the army, which marched without opposition to Quilmes. So far, notwithstanding the low marshy ground and the immense bogs and lakes which intervene between Enseñada and Buenos Ayres, all went well, and it seemed scarcely possible to anticipate any but a favourable result of the enterprise. As no communication could be kept between the naval and land forces, the army had to encumber itself with the immense load of provisions necessary for the subsistence of ten thousand men during one week. For hours together the men were up to their middle in water, their artillery being often swamped in the marshes. Their provisions were scanty and wet; nor was there any shelter from the intense cold, even the supply of wine and spirits running short. The troops marched through a desert, the inhabitants having vanished, together with their horses and cattle.

Buenos Ayres was no longer the timid colonial city which Beresford had found it. The president of the municipality was Señor Alzaga, an energetic partisan of the King, and who carried great authority in the city, where his fortune placed him in the front rank. The people were armed. The national battalions were animated by the best spirit. Liniers, always brave, had now to sustain his high reputation and to win from the Crown the confirmation of the title which he had received from the people. Their past success gave both chief and soldiers confidence. They had seen what street-fighting was, and Whitelocke and his men would have to run the gauntlet of armed streets before reaching the fort.

Such was the spirit by which the colonial forces were animated, when, on the 1st of July, General Whitelocke reached the village of Quilmes, fifteen miles to the south of the town. A force of six thousand eight hundred and fifty men, with fifty-three guns, marched out of the town to defend the passage of the Riochuelo. On the succeeding night the two armies were encamped, respectively, on either bank of the stream which separated them. Next morning at daybreak the Spaniards were drawn up in battle order, anticipating an attack from the enemy; but General Gower, after having exchanged some shots, moved his troops to the left, with the intention of passing the Riochuelo, three miles higher up. Liniers followed his movement, but he did not arrive in time to interfere with his effecting the passage. He, however, succeeded in placing himself between the enemy and the town, near the Miserere, on the south-west of the city.

A combat now took place between the Creole militia and the brigade of General Crawford; but the discipline of the English troops and their great superiority in artillery quickly decided the day in their favour. The Creoles abandoned the field, leaving the whole of their artillery behind. The colonial force then became divided into two bodies. The cavalry, passing the English left, gained the plains. Liniers, who now gave up the town for lost, following the horsemen, gave them orders to rendezvous at Chacharita, a well-known farm three miles to the English rear. This was a wise measure on the part of the general; for had these fugitives entered the town they would doubtless have added to the dismay of the citizens, whilst from this position he could still annoy the English. The infantry took refuge in Buenos Ayres, where the general feeling had now undergone considerable revulsion. The night was cold and wet; the fugitives, worn out by the fatigues of the preceding day, were exhausted and beaten; the general was absent, no one knew where.

And here was renewed the series of infatuated mistakes committed by General Whitelocke. Instead of pursuing the broken enemy and taking advantage of their panic, he allowed them a night of repose, during which the energy of Alzaga was able in a great measure to repair the disastrous effects of the rout of Miserere. The chief of the municipality had not allowed himself to be carried away by the despair of the troops in the absence of the governor; he rather felt stimulated to increased energy. By his orders the soldiers were carefully tended in the municipality and in the barracks, and were cheered with the hope of better fortune in the future. Alzaga likewise caused ditches to be dug in the streets round the principal parade, facing the fort. He also sent messengers to Liniers, who, making a long detour,

succeeded in throwing himself into the town together with his horsemen.

On the morning of the 2nd of July, Buenos Ayres was already in a state of defence. The troops were distributed on the roofs of the churches, on the terraces of the houses, and on the balconies; whilst some pieces of artillery were put in position behind the ditches and behind the barricades which had been erected round the parade and round an open space called the Retiro. Thus when General Gower, who led the advanced guard, summoned the town to surrender, the aspect of affairs was entirely changed from that of the preceding evening; confidence had succeeded discouragement, and good hopes were entertained of yet saving the town. Alzaga replied, that he would not listen to any proposition for the surrender of the garrison.

Under these circumstances the English had to consider their mode of attack, and they employed the following day in making their preparations. On the 4th, the garrison made a sortie, and compelled their assailants to abandon some houses in the suburbs where they had taken shelter. There was also a slight encounter between the 88th regiment and one of mulattoes. The result of these two slight affairs did not fail to encourage the Spaniards.

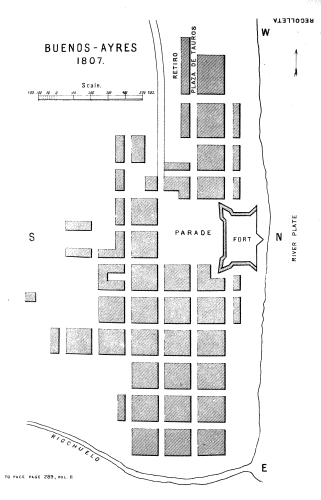

Buenos Ayres, according to a plan before me, at that time consisted of twenty-four square blocks of buildings of a hundred and fifty yards on every side, to the east of the centre parade facing the fort, and of six complete blocks of the same dimensions, together with a number of incomplete ones, lying in the opposite direction. The back of the fort faced the river, having six square blocks to the east and four to the west. The city being laid out on a perfectly regular plan, was divided by parallel streets cutting each other in prolonged lines between the various square blocks of buildings. The central space in front of the fort would have held four blocks; that is to say, it was about three hundred and fifteen yards square. The city was entirely blockaded from the side of the river, and General Whitelocke had the means at his disposal of blockading it in like manner on the other three sides, and thus of very quickly starving it into submission without striking a blow. Since he had failed to take it by a coup de main after the fight of Miserere, this would have been his simplest plan, more especially in view of Beresford’s disastrous experience of street-fighting. It would likewise have had the advantage of being unattended by any appreciable loss of life. He might, on the other hand, have bombarded the town, since its garrison refused to surrender; or, he might have advanced by degrees, clearing out each square block of houses as he proceeded, and making each a ground from which to operate on the next.

But General Whitelocke seemed infatuated, and left no one thing undone to play into the enemy’s hands. Having given orders that his troops should not load their pieces, lest they might be tempted to delay for the purpose of returning the enemy’s fire, he divided his entire force into eight bodies, who should penetrate simultaneously into the town, and, disregarding the street-fire which was sure to be poured upon them from the tops of the flat-roofed houses, should make straight for the river, whence, turning to the right and to the left, respectively, they should make for the central parade and occupy the highest buildings.

In accordance with the above plan, the 45th regiment, which was on the right, penetrated without difficulty to the Residencia, of which it took possession. The light division, composed of rifles and light infantry, notwithstanding a hail of balls which fell on it from the balconies, windows and roofs, was able to arrive in front of the Dominicans’ convent; and, breaking open the gates, the men penetrated into the church, where they found the flags which had been taken from the 71st in the previous year. Ascending the turrets, the rifles there hoisted the same flags, and from this commanding position they directed a very effective fire on the citizens who occupied the terraces of the neighbouring houses. But the fort, perceiving the English flag on the towers of the convent, directed towards it such a cannonade that the English who were there shut up and who had been meanwhile cut off there by the militia, were forced to surrender at discretion. One of the prisoners was Colonel Pack, who had already been made prisoner with Beresford, and who, having escaped, had joined in the attack on the convent of San Domingo.

Another English column, under the orders of Colonel Cadogan, after having lost a fourth of its number, was obliged to lay down its arms, being enclosed in a circle of fire near the Jesuits’ college. A like fate befell the 88th regiment under Duff, after it had penetrated by the central streets to the parade. The 36th regiment, which had entered by the streets of Corrientes and of Tucuman, was compelled to fall back on the Retiro, in spite of the heroic efforts of General Lumley. The 5th regiment, having suffered less, arrived at the convent of St. Catherine, where it took up its quarters, to the scandal and terror of the nuns.

The 87th regiment, under the orders of Auchmuty, had attacked the Retiro and had been cut up by the fire of the troops shut up in the Plaza de Tauros; but Colonel Nugent, having seized a battery which defended the approaches on this side, turned the guns against the edifice occupied by the Spaniards, and the six hundred men who had resisted the attack of Auchmuty, being crushed by the fire of Nugent, were obliged to surrender.

Night put an end to the dismal combat. The 5th regiment remained in the convent. Auchmuty and Whitelocke were besieged in the Retiro. The greater part of the 45th occupied the Residencia together with a German battalion which had been left as a reserve. This fatal day had cost the English 1130 men killed and wounded, amongst whom were seventy officers. There were likewise made prisoners and shut up in the convents and barracks, a hundred and twenty officers and fifteen hundred soldiers, after having surrendered their arms and ammunition to the local militia or the citizens.

On the morning of the 6th General Whitelocke had still at his disposal some five thousand effective men. He placed himself in communication with the fleet, from which he could receive provisions and reinforcements, as well as big guns to use against the town.

Liniers seeing that it was still possible for either side to fight, and wishing to avoid an unnecessary effusion of blood, took the bold step of sending a flag of truce to the English general, with the proposal to surrender all his prisoners, including those taken with Beresford, providing he should consent to at once embark with all his forces, and depart.

And now occurred an incident which, but for its grave consequences, would border on the ludicrous. In drawing up his communication to the English general, Liniers had merely stipulated that in return for his prisoners, the latter should evacuate the territory of Buenos Ayres. Being a brave officer himself, it never occurred to him that General Whitelocke, who was still in possession of Monte Video, and at the head of an army of seven thousand effective men, not to speak of the fleet, could be asked to surrender his hold on Uruguay. But Alzaga thought otherwise. He insisted that the terms of convention should include the surrender of Monte Video. Liniers remonstrated that they had not taken Monte Video, and that they might be quite satisfied by obtaining the relief of Buenos Ayres. To this Alzaga replied that there could be no harm in inserting a clause demanding the restoration of Monte Video, since, at the worst, it could only be objected to. The clause was accordingly inserted—and complied with without remonstrance.

When Whitelocke received the above proposals he at first rejected them; but he nevertheless demanded an armistice of twenty-four hours to carry away the wounded. Liniers, whose wounded were safely housed, replied by reopening a fire on the Retiro. The English made a sortie, in which they are said to have suffered even more than on the day preceding. The Buenos Ayrian writers admit that the English troops, officers and soldiers alike, penetrated through the deadly streets with the utmost intrepidity; but their confidence was entirely broken, as well it might be, when they saw themselves the victims of such a general. They fought as it was their duty to fight, but not with the least hope of conquering. The colonists, on the other hand, were full of confidence; and Alzaga was more than ever determined that the terms of capitulation should include Monte Video.

In the course of the afternoon General Gower presented himself at the fort under a flag of truce. He was the bearer of propositions from General Whitelocke almost identical with those that had been drawn up by Liniers under the advice of Alzaga. The English plenipotentiary was received by Liniers, by Generals Balbiana and Velasco, and by the Mayor Alzaga. The proposals of General Whitelocke were accepted; forty-eight hours were accorded to the English in which to evacuate Buenos Ayres, and the term of two months for embarking from Monte Video, and quitting every part of the Plata. The capitulation was ratified next day (the 7th of July) by the English general, and the city of Buenos Ayres not unnaturally gave itself over to triumph when, on the following day, it saw the English ships weigh anchor previous to their departure.