полная версия

полная версияA Little Preserving Book for a Little Girl

The addition of the quince juice made the flavor of the apples delicious.

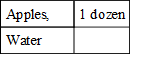

Canned Apples (without sugar)

Wiping the apples clean, Adelaide pared them with the sharp knife, cut them into quarters and removed the core. If the apples were very juicy she did not need to cook them in very much water, otherwise the water (which she poured over the apples boiling) came nearly to the top of the apples.

Placing the saucepan over the fire, the fruit boiled slowly until tender, then Adelaide at once filled to overflowing the sterilized pint jar. Inserting a silver knife between the jar and the fruit, she let the air bubbles rise to the top and break.

The new rubber, dipped in boiling water, was placed on smoothly, and the jar sealed quickly, then Adelaide stood it upside down out of the way of any draft. In the morning she wiped off all stickiness with a damp cloth from the outside of the jar, inspected it carefully for any possible leaks, pasted on the label and stored the apples in the preserve closet.

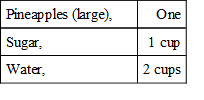

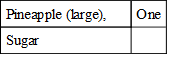

Canned Pineapples No. 1

Mother had to show Adelaide how to remove the skin and eyes from the pineapple. Adelaide found it a rather prickly thing to handle, but after it was ready, she cut it into slices fairly thick, and removed the little hard core with a sharp knife. Mother told her she could leave the slices whole, or she could cut them into cubes. Adelaide said that she preferred cutting them into cubes.

The cup of sugar and two cups of water were measured into the saucepan, which she placed over the fire and let boil ten minutes, then the pineapple was dropped in and cooked until tender, or until you could pierce it easily with a silver fork.

As soon as it had cooked sufficiently, Adelaide filled the sterilized pint jar, first with the fruit, and then poured in the syrup so that it overflowed. Next she inserted a silver knife between the pineapple and the jar, to let the air bubbles rise to the top and break. The new rubber, which had been dipped in boiling water, was placed around the top smoothly, then Adelaide sealed it quickly and stood the jar upside down out of the way of any draft.

In the morning she wiped all stickiness off the jar with a damp cloth, examined the jar carefully to be sure there were no leaks, pasted on the label and stored the canned fruit away in the preserve closet.

Another way that mother liked to put up pineapples is as follows:

Canned Pineapples No. 2

Adelaide, after removing the skin and eyes from the pineapple, cut it into quarters lengthwise and removed the cores. Then she weighed it, after which she put the pineapple through the meat chopper.

Into the saucepan she measured one-half its weight of sugar and added the chopped pineapple.

Placing the saucepan over the fire, Adelaide let the fruit and sugar come slowly to the boiling point, stirring frequently with the wooden spoon to keep from burning. After the boiling point was reached, the fruit cooked slowly for twenty minutes, and Adelaide put it into the sterilized pint jar at once. The jar was filled to overflowing and a silver knife inserted between the fruit and the jar, to let all air bubbles rise to the top and break.

Next she placed a new rubber around the top smoothly, sealed it quickly and stood it upside down out of the way of any draft.

In the morning she examined the jar carefully to see that it did not leak, wiped off all stickiness with a damp cloth, pasted on the label and stored the finished product away in the preserve closet.

Mother often used pineapple put up in this manner for pineapple ice cream, or pineapple sherbet. It made a delicious dessert.

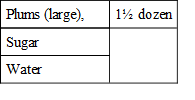

Canned Plums

The large blue plums, the green-gage plums, or the large red plums, were all put up in the same manner.

Adelaide wiped each plum thoroughly with a damp cloth, cut it in halves with a silver knife, and removed the stone. Then she weighed them. To each pound of fruit Adelaide measured one cup of water and one cup of sugar. The plums and the water she placed in the saucepan over the fire and let them come slowly to the boiling point, while the sugar was heating at the back of the range in an earthenware dish.

Adelaide boiled the plums gently, stirring occasionally with a wooden spoon, until they were tender or until you could pierce them with a silver fork easily. It usually took twenty minutes. The sugar was then ready to add to the fruit, and Adelaide stirred the mixture very carefully until it was all dissolved. As soon as the fruit boiled up Adelaide canned at once. She lifted each plum carefully with a silver fork into the sterilized pint jar, then poured in the juice till it overflowed. Inserting a silver knife between the fruit and the jar, Adelaide let the air bubbles come to the top and break. The new rubber, after being dipped in boiling water, was fitted on smoothly, then she sealed the jar quickly and stood it upside down out of the way of any draft.

In the morning, with a damp cloth she wiped off all stickiness from the outside of the jar, inspected it carefully to be sure that it did not leak, pasted on the label and stored the jar away in the preserve closet.

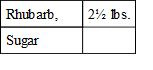

Canned Rhubarb

If the rhubarb is pretty in color and young and tender, mother told Adelaide that she did not need to peel the stalks, but just wash and wipe them clean and cut them in small pieces with the little sharp knife. Then she weighed the fruit and allowed one-half pound of sugar to each pound of rhubarb. Both sugar and rhubarb were put in the saucepan and placed over the fire to come very slowly to the boiling point. Adelaide stirred constantly with a wooden spoon to prevent burning, and as soon as it had boiled fifteen minutes she poured it into the sterilized pint jar. The silver knife she inserted between the jar and the fruit, to let all air bubbles rise to the top and break. After the new rubber was dipped in boiling water and placed over the jar smoothly, Adelaide sealed it quickly, then stood the jar upside down out of the way of any draft. In the morning she inspected the jar carefully to be sure that there were no leaks, wiped off all stickiness with a damp cloth, pasted on the label and stored the jar away in the preserve closet.

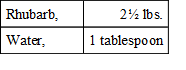

Sometimes mother canned rhubarb without sugar, so Adelaide tried a jar. Mother said the flavor was much better and it was not so juicy, also it was excellent for pies, shortcakes, etc., adding the sugar when you used it.

Canned Rhubarb (without sugar)

Adelaide washed and wiped each stalk thoroughly, then cut it into small pieces. These she put in the saucepan with a tablespoon of cold water to keep from burning, and stirred with a wooden spoon. She let the fruit heat very gradually and boiled slowly for fifteen minutes. It was then ready to can, and Adelaide poured the rhubarb into the sterilized pint jar at once, after which she inserted a silver knife between the jar and the fruit, to let all air bubbles rise to the top and break. Next came the new rubber, which she dipped in boiling water, placed over the top smoothly, then sealed quickly. Standing the jar upside down she stood it out of the way of any draft. In the morning Adelaide examined the jar carefully to be sure that it did not leak, wiped off the outside with a damp cloth, pasted on the label and stored the jar away in the preserve closet.

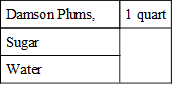

Damson Plum Preserves

The Damson plums Adelaide wiped thoroughly, and pricked each one with a silver fork twice. Then she weighed the fruit. To each pound she measured three-quarters of a pound of sugar. To each pound of sugar Adelaide measured one cup of water. The sugar and water she put in the saucepan and placed over the fire. When the syrup boiled, Adelaide skimmed it and added the plums. The plums Adelaide cooked until they were tender, stirring them carefully with a wooden spoon so as not to break the fruit, then filled the sterilized pint jar to overflowing. A silver knife was inserted between the fruit and jar to let all air bubbles rise to the top and break. The new rubber was dipped in boiling water, placed over the top smoothly and the jar sealed quickly. This Adelaide stood upside down out of the way of any draft. In the morning the jar was carefully examined to see that it did not leak, all stickiness was wiped off with a damp cloth, the label was pasted on, and then Adelaide stored the jar away in the preserve closet.

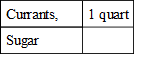

Preserved Currants

The currants Adelaide picked over carefully and put into the colander. This she placed in a pan of clear cold water and dipped up and down several times until quite clean. After they had drained well she weighed them, and to each pound of fruit she measured a pound of sugar. Half of the currants Adelaide put in the saucepan and placed on the fire to heat through. When they were thoroughly warmed she removed the saucepan from the fire and mashed the currants with the wooden potato masher, then she strained the juice through the jelly bag.

The juice and sugar Adelaide put into the saucepan and boiled gently for fifteen minutes, after which she added the other half of the currants. It took the currants only five minutes to just cook through and they remained whole in the jelly.

This was poured into sterilized tumblers. When cold the tumblers were wiped free from all stickiness, and Adelaide sealed them by pouring melted paraffin over the top, shaking it gently from side to side to exclude all air. Pasting on the labels she stored them away in the preserve closet.

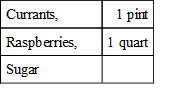

Preserved Currants and Raspberries

The currants and raspberries Adelaide picked over and kept separate. She did not forget to look carefully in the center of each raspberry to be sure that there were no little worms. After washing the currants, placing them in the colander and dipping it up and down several times in a pan of clear cold water she poured them into the saucepan and mashed them with the wooden potato masher. Adelaide washed the raspberries in the same manner, but stood them aside to drain while the currants were cooking. The currants simmered slowly for half an hour (or until the currants looked white), and then the juice was strained through the jelly bag. Adelaide returned the juice to the saucepan, and added the sugar. (The currants and berries had been weighed after washing them, and to each pound of fruit she measured three-fourths of a pound of sugar.)

The juice and sugar boiled slowly for twenty minutes, then Adelaide poured in the raspberries carefully and cooked three minutes more.

Into the sterilized pint jar she skimmed the raspberries, then added the juice to overflowing. The silver knife was inserted between the jar and the fruit, to let all air bubbles rise to the top and break, the new rubber was placed on smoothly and Adelaide sealed the jar quickly. It was then placed upside down out of the way of any draft. In the morning the jar was carefully inspected for any leaks, wiped free from all stickiness with a damp cloth and the label pasted on. Adelaide then stored it away in the preserve closet.

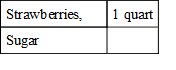

Preserved Strawberries

Before hulling the strawberries, Adelaide put them into the colander and dipped it up and down several times in a pan of clear cold water to cleanse the berries thoroughly. After hulling the fruit she weighed it, and for each pound she weighed a pound of sugar.

The strawberries were put into the saucepan and the sugar sprinkled over them and they stood until the juice ran freely. Then the saucepan was placed on the fire and the fruit and sugar heated through. Adelaide stirred with the wooden spoon, being careful not to break the strawberries.

When the sugar was all dissolved and the berries thoroughly heated, Adelaide skimmed the berries out into a dish. The syrup then boiled for ten minutes slowly, after which the strawberries were dropped in carefully and boiled two minutes. Into the sterilized pint jar Adelaide skimmed all the berries, filled it to overflowing with the syrup, inserted a silver knife between the fruit and the jar to let all air bubbles rise to the top and break, placed on the new rubber smoothly, sealed the jar quickly and stood it upside down out of the way of any draft.

In the morning she examined the jar carefully to see that it did not leak, wiped off all stickiness with a damp cloth, pasted on the label and stored the preserved berries away in the preserve closet.

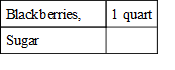

Preserved Blackberries

After picking over the blackberries Adelaide placed them in the colander and dipped it up and down in a pan of clear cold water several times to remove all dust and dirt. After weighing the berries she poured them into a saucepan and sprinkled over them an equal weight of sugar. These stood for an hour before Adelaide put the saucepan over the fire and let the berries and sugar come slowly to the boiling point. Adelaide stirred them gently with a wooden spoon, being careful not to break the fruit.

When they boiled up she skimmed out the blackberries into a dish and the syrup cooked for five minutes.

Returning the blackberries to the syrup she put the saucepan at the back of the range and let the fruit slowly heat without stirring. After they had stood fifteen minutes she poured the berries at once into the sterilized pint jar, filling it to overflowing. With a silver knife, which she inserted between the jar and the fruit, she let all air bubbles rise to the top and break. Placing a new rubber over the top smoothly she sealed quickly and stood the jar upside down out of the way of any draft. In the morning it was ready to be inspected carefully for any leaks, and she wiped off all stickiness with a damp cloth, pasted on the label and stored the fruit away in the preserve closet.

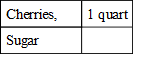

Preserved Cherries

Adelaide washed the cherries in the colander, which she dipped up and down several times in a pan of clear cold water. She took off the stems and removed the stones, weighed the cherries and added a pound of sugar to each pound of fruit. Then she let them stand over night, and the next morning put them into the saucepan to cook slowly until clear and tender, stirring carefully with a wooden spoon so as not to break the fruit.

When they were done Adelaide picked out the cherries first with the skimmer and dropped them into the sterilized pint jar, then she filled it to overflowing with the syrup, inserted a silver knife between the fruit and the jar to let all air bubbles rise to the top and break, placed on a new rubber smoothly, sealed quickly and stood the jar upside down out of the way of any draft.

In the morning she inspected the jar carefully to be sure that it did not leak, wiped off all stickiness with a damp cloth, pasted on the label and stored the jar away in the preserve closet.

"Mother," said Adelaide one morning, "it is not nearly as discouraging to preserve as it is to just plain cook."

"Why, what do you mean, dear?" answered mother.

"Well, I've been thinking how quickly we eat up things you cook for us every day, while my jams and jellies are still in the preserve closet," mused Adelaide.

"Just wait until next winter, young lady, then you'll see how quickly they will disappear," laughed mother.

CHAPTER V

CONSERVES

When Adelaide came to "conserves," mother told her she had only a very few recipes, but that what they lacked in numbers they made up for in quality.

"Have you the recipe for 'Peach conserve'?" asked Adelaide anxiously.

"Oh, yes, dear, that is our favorite, and I don't know how many people have asked me how to make it. I couldn't possibly keep house without it," answered mother.

Conserves, mother explained to Adelaide, were very similar to jams, with the addition of lemon or orange juice, raisins and nuts.

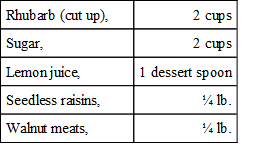

Rhubarb Conserve

Mother picked out the pinkest, prettiest rhubarb she could find, then Adelaide washed and wiped each stalk and cut it into small pieces. When she had filled the cup with rhubarb twice she put it into the saucepan and poured over it two cups of sugar and a dessert spoon of lemon juice.

Adelaide next measured out a fourth of a pound of seedless raisins. Upon these she poured boiling water which stood a minute or two, then she drained them. After looking them over carefully to remove any stems, she added them to the rhubarb, sugar, etc. Twelve or fourteen large walnuts were sufficient to crack. The meats Adelaide put through the meat chopper and added to the rest of the good things.

After standing three hours the saucepan was placed on the fire and the conserve came slowly to the boiling point. Adelaide stirred the mixture frequently with a wooden spoon while it boiled for twenty minutes. It was then ready to pour into the sterilized tumblers.

When the conserve was cold, Adelaide wiped around the top and the outside of each tumbler with a damp cloth, poured melted paraffin over the top (which she shook gently from side to side to exclude all air), pasted on the labels and stored the glasses away in the preserve closet.

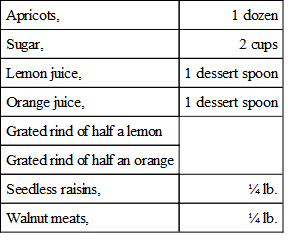

Apricot Conserve

Adelaide wiped the apricots thoroughly with a damp cloth, then cut them in halves with a silver knife and removed the stones. These she placed in a saucepan, poured over them two cups of sugar, a dessert spoon each of lemon and orange juice, and the grated rind of half a lemon and half an orange. Next she measured out a fourth of a pound of seedless raisins and covered them with boiling water for a few minutes, after which she drained them and picked off any stems. Twelve or fourteen large walnuts were sufficient to crack, and the walnut meats and the raisins Adelaide put through the meat chopper, then added these to the fruit in the saucepan.

Placing the saucepan over the fire she heated it through slowly and let the fruit boil for forty minutes. Adelaide stirred the contents of the saucepan constantly with a wooden spoon, and when it was done, poured it at once into the sterilized tumblers.

As soon as it was cool she wiped the tops and outsides with a damp cloth, poured melted paraffin over the conserve, shaking the tumblers from side to side to exclude all air, pasted on the labels and stored the jars away in the preserve closet.

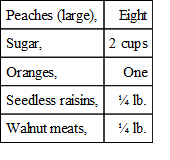

Peach Conserve

To remove the skins from the peaches easily, Adelaide poured boiling water over them. Letting them stand for a minute or two, she then peeled off the skins with a silver knife and sliced the peaches into small pieces, throwing away the stones. Placing the peaches into a saucepan she added two cups of sugar. After weighing out one-fourth of a pound of seedless raisins she covered them with boiling water for about a minute, drained, and picked off any stems. The walnuts (twelve or fourteen large ones) she cracked and put with the raisins.

The rind of the orange she grated over the sugar and peaches, and then, after removing the seeds, Adelaide put the pulp of the orange, the raisins and the nuts through the meat chopper.

When everything was in the saucepan together, Adelaide placed it over the fire and let it come slowly to the boiling point, and then cook gently for an hour. Adelaide stirred frequently with a wooden spoon to prevent burning, and when the conserve had cooked sufficiently she poured it into the sterilized tumblers.

As soon as it was cold, she wiped around the top and outside of each tumbler with a damp cloth, poured melted paraffin over the conserve (shaking it gently from side to side to exclude all air), pasted on the labels and stored the glasses away in the preserve closet.

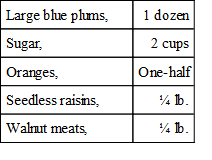

Plum Conserve

After washing and wiping the plums thoroughly, Adelaide cut them in halves with a silver knife, and removed the stones. Placing them in the saucepan she poured two cups of sugar and the grated rind of half an orange over them. Twelve or fourteen large walnuts were cracked and the meats taken out. Over the quarter of a pound of raisins (which she weighed) Adelaide poured boiling water. These stood thus for about a minute, then she drained off the water and picked out the stems.

The raisins, the walnut meats, and the pulp of the half orange Adelaide put through the meat chopper and added to the plums, etc. in the saucepan. Placing the saucepan over the fire she let the contents come slowly to the boiling point, stirring it occasionally with the wooden spoon. It cooked gently for one hour, and then Adelaide poured the conserve at once into the sterilized tumblers.

When it was cold the tops and outsides were wiped off carefully with a damp cloth, melted paraffin was poured over the top and shaken gently from side to side to exclude all air, the labels were pasted on and then the conserve was stored away in the preserve closet.

The green-gage plums and the large red plums would make an equally delicious conserve, mother said, and she thought it would be nice to substitute figs sometimes in place of raisins. As the foregoing recipes were all she had, mother told Adelaide that it was just as well to leave further experimenting until another year. Adelaide was very willing, as she was eager to try "Spiced Fruits."

CHAPTER VI

SPICED FRUITS

"When you were a tiny little baby," said mother, "I had a young girl living with me who taught me how to put up Spiced Currants. She had lived in the country, and her favorite aunt was renowned for her tempting preserves."

"Oh, mother," interrupted Adelaide, "do you think I could ever become renowned, or whatever you called it?"

"I think there is no reason why you shouldn't, if you continue to do as good work in the future as you have thus far. Every year you will become more expert, and find out many new combinations that especially suit your taste and appeal to others," answered mother. "All spiced fruits," she continued, "are particularly tasty when served with cold meats."

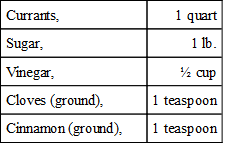

Spiced Currants

Adelaide picked over the currants and removed the stems. Putting the currants into the colander, she dipped it up and down several times in a pan of clear cold water, then set it aside to drain. Into the saucepan she poured the currants, added one pound of sugar, a half a cup of vinegar, and a teaspoon each of cloves and cinnamon.