полная версия

полная версияThe 56th Division

Practice attacks, based on these instructions, were carried out by the brigades in reserve.

We have written of the constructive preparations which were going on all along the line of proposed attack. These preparations were continued until the last moment. But meanwhile another element was introduced—that of destructive preparation. It is scarcely necessary to point out that neither form of preparation could be concealed from the enemy. The Germans knew as well as we did where we would attack.

The Gommecourt sector to be attacked was held by the German 169th and 170th Regiments, with about 1-1/2 battalions on the front line, 1 battalion in support, 2 battalions in reserve in Bucquoy, and 2 companies at Ablainzeville. Their artillery consisted of 5 batteries of heavy artillery and 12 batteries of field artillery. These batteries were divided into three groups at Quesnoy Farm, on the left of the British position, Biez Wood and Puisieux. There was a further group of guns near Adinfer Wood which could assist in the defence.

The 56th Divisional Artillery, together with the heavy VII Corps guns, had now to prepare for the infantry assault by smashing up not only the wire and trench system, but billets and gun positions behind the German lines as well. As regards villages, most attention was given to Bucquoy, Essart, Ablainzeville, and Achiet-le-Grand.

Three groups of artillery were formed—a northern group, under Lieut.-Col. Southam, a southern group, under Lieut.-Col. Macdowell, and a wire-cutting group under Lieut.-Col. Prechtel. The northern and southern groups were under the orders of the Corps, and consisted of:

Northern Group3 batteries of 18-pounders (until zero day, then 4 batteries).

1 battery 4·5 howitzers.

Affiliated at zero to the 169th Brigade.

Southern Group4 batteries of 18-pounders.

1 battery 4·5 howitzers.

Affiliated at zero to the 168th Brigade.

Wire-cutting Group5 batteries of 18-pounders until zero and then 4 batteries.

1 battery 4·5 howitzers.

Two of the guns of the 4·5 battery will be at the call of the counter-battery group.

In the preliminary instructions it will be noticed that a party of officers and men were detailed to act under the Divisional Gas Officer. Their special duty was to cover the approach of the infantry by the discharge of a smoke cloud. It was hoped to introduce some element of surprise by occasional discharges of smoke during the preparatory bombardment, and so the Corps ordered that the bombardment should be carried out for a period of five days, and the attack would take place on the sixth. These days would be known as U, V, W, X, Y, and Z days.

“Smoke discharges lasting for a period of ten minutes will take place on the days and at the hours mentioned below. They will coincide with the intense artillery bombardment of the enemy trenches. These bombardments will commence thirty minutes before the smoke, and will reach their maximum intensity during the ten minutes that it is being discharged:

U day, no discharge.

V day, no discharge.

W day from 10.15 a.m. to 10.25 a.m.

X day from 5.45 a.m. to 5.55 a.m.

Y day from 7.15 a.m. to 7.25 a.m.

On Z day the smoke cloud will commence five minutes before zero. On the 46th and 56th Divisional fronts its duration will be as arranged by divisions. On the 37th Divisional front it will continue for one hour.”

U day was the 24th June, but the whole of the great attack was postponed for two days, so that, instead of having five days of the preliminary bombardment, there were seven.

Naturally the Germans did not sit still under this destructive fire, but retaliated on our front line and trench system, and on our rear organisation. The enemy artillery had been active during the month of May, and the division had suffered in casualties to the extent of 402; for the month of June casualties leapt up to 801. The end of June was a prolonged crash of guns. Only for one half-hour, from 4 p.m., did the guns cease so that aeroplanes might take photographs of the German lines, and then the sky was speckled with the puffs of smoke from the German anti-aircraft guns.

The guns of the 56th Division fired altogether 115,594 rounds, of which 31,000 were fired on Z day. To this total must be added the work of the Corps heavy artillery. The 6-inch, 9·2-inch, and 15-inch fired on V day 3,200 rounds, on W day 2,200 rounds, on X day 3,100 rounds, and on Y day 5,300 rounds (which was repeated on the two extra days) at the front-line trenches and strong points. 6-inch, 9·2-inch, 4·7-inch, 4·5-inch, and 60-pounder guns also dealt with the villages of Bucquoy, Achiet-le-Grand, Essart, and Ablainzeville, but in nothing like the same proportion of rounds.

The first smoke cloud was discharged on the 26th June, and drew very little hostile machine-gun fire. The enemy lines were reported to be much damaged on that day. On the 27th the smoke discharge was somewhat spoilt by the premature bursting of a smoke shell an hour before the appointed time. This misfortune caused the enemy to put down a barrage on our front-line and communication trenches, which prevented the smoke detachments getting to their appointed positions. When the cloud was eventually discharged there was a large gap in the centre of it, so it must have been obvious to the enemy that it was only a feint.

The continual bombardment became more intense, and the enemy reply more vigorous. On the 28th the enemy wire was reported as satisfactorily cut in front of their first and second lines. Observers also noted that there was considerable movement of troops behind the German lines.

Every night, the moment it was dark, although the artillery still pounded trenches, roads, and tracks, patrols crept forward to ascertain what progress had been made in the battering down of defences. 2/Lieut. P. Henri, of the 3rd London Regt., raided the front line. He found the Germans working feverishly to repair their trench, and succeeded in capturing one prisoner, who proved to be of the Labour Battalion of the 2nd Reserve Guards Division. He reported that the wire in some places still formed a considerable obstacle.

A patrol of the 1st London Regt. reported, on the 29th, that new French wire and some strands of barbed wire had been put up. Up to the last moment the Germans worked at their defences. Great activity was seen on the morning of the 30th.

The artillery grew more furious. A hail from heavy and field-gun batteries descended on trenches and strong points. Lieut.-Col. Prechtel’s wire-cutting group pounded away at the wire. The trench mortar batteries added their quota, though they were chased from pillar to post by German retaliation. And as the evening shadows fell on the last day, the usual night firing was taken up by the never-wearying gunners.

* * * * * * *The main object of this attack was to divert against the VII Corps enemy artillery and infantry, which might otherwise have been used against the left flank of the Fourth Army at Serre. To achieve this result the two divisions, 46th and 56th, were given the task of cutting off the Gommecourt salient.

From the 24th to the 30th June the line of the 56th Division was held by the 167th Brigade. The other two brigades then practised the assault on a replica of the German defence system near Halloy. In the early morning of the 1st July the 168th and 169th Brigades took over the line, and the 167th withdrew to Hébuterne.

The 5th Cheshire Regt. had a company with each of the assaulting brigades; the Royal Engineers sent a section of the 2/1st London Field Coy. with the 169th Brigade, and a section of the 2/2nd London Field Coy. with the 168th Brigade.

The London Scottish attacked on the right with the Kensingtons in support; then came the Rangers with the 4th London Regt. in support. The rôle of these battalions of the 168th Brigade may be briefly described as a half-wheel to the right. They had to capture the strong point round about Farm and Farmer trenches, and establish other strong points at Elbe and Et, south-east of Nameless Farm, and the junction of Felon and Epte.

On the extreme left of the division was the London Rifle Brigade, and next to them the Queen Victoria’s Rifles. Again as a rough indication of their task, they had to make a left wheel and hold the line of the edge of Gommecourt Park, establishing strong points. The Queen’s Westminster Rifles would then push straight on, carrying the attack forward, as it were, between the right and left wheels, and capture the strong point known as the Quadrilateral.

At 6.25 a.m. every gun opened on the German lines, and for one hour the enemy was pelted with shells of all sizes, the maximum speed of fire being reached at 7.20 and lasting for ten minutes. At this moment smoke was discharged from the left of our line near Z hedge, and in five minutes the smoke was dense along the whole front. Then the assaulting battalions climbed out of their trenches and advanced steadily into the heavy fog.

The German front line was reached with little loss—there was machine-gun fire, but it was apparently high. Almost immediately, however, the Germans gave an indication of their counter-measures—they were reported by the London Scottish to be shelling their own line. This gallant regiment succeeded in gaining practically the whole of its objectives, but they were never very comfortable. Owing to the smoke the two left companies lost direction, the flank company being drawn off in the direction of Nameless Farm, and the inner company failed to recognise its position and overran its objective. This was in no way surprising, as it was extremely difficult, owing to the heavy bombardment, to find, in some places, any trench at all.

Next to the London Scottish the Rangers met with strong resistance, and probably strayed a bit to their left. They were soon in trouble, and two companies of the 1/4th London Regt. were sent forward to reinforce them. Together these two units succeeded in reaching the junction of Epte with Felon and Fell, but there was a gap between them and the London Scottish.

On the left of the attack the London Rifle Brigade had swept up to the edge of Gommecourt Park and commenced to consolidate their position. The Queen Victoria’s Rifles, on the other hand, were meeting with fierce resistance, and were short of the Cemetery. The Queen’s Westminster Rifles, advancing in rear, soon became hopelessly mixed up with the Queen Victoria’s Rifles. Within an hour it became clear that the infantry were everywhere engaged in hand-to-hand fighting.

The German counter-attack plans matured about an hour after the assault was launched. Their barrage on No Man’s Land was increased to fearful intensity, and from Gommecourt Park, which was apparently packed with men in deep dugouts, came strong bombing attacks. The London Rifle Brigade called for reinforcements, but platoons of the reserve company failed to get through the barrage and across to the German front line.

The assaulting companies had been provided with boards bearing the names of the trenches to be captured, and as they fought their way forward, these boards were stuck up to mark the advance. At about 9.30 a.m. the artillery observers, who did most useful and gallant work during the whole action, could report that all objectives were gained with the exception of the Quadrilateral. But the troops in the German lines were now held there firmly by the enemy barrage; they were cut off from all communication by runners, and from all reinforcements. On the right the Kensingtons had failed in an attempt to reinforce the London Scottish. Captain Tagart, of the former regiment, had led his company out, but was killed, and of the two remaining officers, one was killed and the other wounded. A confused message having reached headquarters, a fresh officer was sent down with orders to rally the men and make another attempt to cross the inferno of No Man’s Land. He found that there were only twenty men left, and that to cross with them was impossible.

The Royal Flying Corps contact machine, detailed to report on the situation, sent constant messages that the Quadrilateral was empty of troops of either side. The artillery observers, however, reported seeing many parties of hostile bombers moving through the Park, and enemy troops collecting behind the Cemetery.

It seemed as though all battalions had at one time gained their objectives except the Queen’s Westminster Rifles, but no blame falls on this fine regiment. Lieut.-Col. Shoolbred says in his report, “As no officer who got as far as this (first line) ever returned, it is difficult to know in detail what happened.” The three captains, Cockerill, Mott, and Swainson, were killed before reaching the second German line. Apparently the wire on this section of the front was not satisfactorily dealt with. The report says:

“A great deal of the wire was not cut at all, so that both the Victorias and ourselves had to file in, in close order, through gaps, and many were hit.... The losses were heavy before reaching the bank at the Gommecourt-Nameless Farm road. At this point our three companies and the two Victorias were joined up and intermixed.... Only one runner ever succeeded in getting through from the assaulting companies.”

There were a few brave young officers of the Queen’s Westminsters left at this point—2/Lieuts. J. A. Horne, A. G. V. Yates, A. G. Negus, D. F. Upton, E. H. Bovill. They proceeded to collect their men and lead them forward, and while doing this 2/Lieuts. Yates and Negus were killed. 2/Lieut. Upton, having then reorganised a bombing party, bombed the enemy out of Fellow and reached the Cemetery. To do this they had to run over the open and drop into Fellow. Another party tried at the same time to bomb their way up Etch, but found it was too strongly held by the enemy. Meanwhile, 2/Lieut. Upton had stuck up his signboard, and more men doubled up over the open and dropped into Fellow Trench. 2/Lieut. Horne then mounted a Lewis gun, under cover of which a platoon of the Cheshire Regt. and some Royal Engineers blocked Etch and also Fell (it would seem doubtful, from this statement, whether Fell was ever held).

Sergt. W. G. Nicholls had kept a party of bombers together and, led by a young lieutenant of the Cheshire Regt., whose name unfortunately is not mentioned [we believe it was 2/Lieut. G. S. Arthur], this party forced its way from the Cemetery to the Quadrilateral. The names of some of the men are given by Col. Shoolbred:

“Cpl. R. T. Townsend, L/Cpl. W. C. Ide, Cpl. Hayward, Rfn. F. H. Stow undoubtedly did reach the Quadrilateral, where strong enemy bombing parties met them, and the Cheshire lieutenant ordered the party to retire, apparently trying to cover their retirement himself, as he was not seen again.”

In any case this advance into the Quadrilateral was but a momentary success, and it may be said that the attack never got beyond the German third line. Signals were picked up by the artillery observers calling for bombs. As early as 10 a.m. two parties of London Scottish, each fifty strong, attempted to take bombs across to their comrades. None got to the German first line, and only three ever got back to ours.

About midday the enemy was launching concerted counter-attacks from all directions. He was coming down Epte, Ems, and Etch, he was coming from Gommecourt Park, he was in Fall on the right. More desperate attempts were made to reinforce the hard-pressed troops. Capt. P. A. J. Handyside, of the 2nd London Regt., led his company out to try and reach the left of the line. He was hit, but struggled on. He was hit again and killed as he led a mere half-dozen men into the German first line.

Capt. J. R. Garland, also of the 2nd London Regt., attempted the same feat with his company, and met with a like fate. All the officers of both companies were casualties.

At 2 p.m. the London Scottish still held firm on the right and the London Rifle Brigade on the left—indeed, 2/Lieut. R. E. Petley, with thirty men, hung on to Eck three hours after the rest of his battalion had been ordered to fall back on Ferret, the German first line. But, although the two flanks held, the troops in the centre were gradually forced back until isolated posts were held in the second German line. By 4 p.m. nothing more was held than the German first line.

By 9 p.m. everyone who could get there was back in our own lines.

But we must not leave our account of the fighting with the story of the 46th Division untold. It was not unreasonable for the men of the 56th Division to hope, while they were being hardly pressed, that the 46th Division might suddenly come to their aid. Perhaps luck would favour that division!

The attack from the north was launched between the Gommecourt road and the Little Z. The 137th Brigade, with the 6th South Staffordshire Regt. on the right and the 6th North Staffordshire Regt. on the left, had Gommecourt Wood in front of them. The 139th Brigade, with the 5th Sherwood Foresters on the right and the 7th Sherwood Foresters on the left, carried the attack up to the Little Z.

The account of this action is one long series of disasters. It seems that the South Staffords on the right started by getting bogged in the mud. A new front line had been dug, but they could not occupy it for this reason. They filed out through gaps in their wire, and if any succeeded in reaching the German front line it was for a period of minutes only. The North Staffords fared no better, though a few more men seem to have gained the enemy first line, but were, however, quickly forced out. The utmost confusion reigned in that part of the line, and the attack, from the very start, was futile.

The 5th and 7th Sherwoods got away to time (7.30), but

“there was a little delay in the fourth wave getting out, owing to the deep mud in the trenches, and still more delay in the carrying parties moving up (due to a similar reason), and also on account of the enemy barrage of artillery, rifle, and machine-gun fire which became very heavy on our old front line.... Of the 5th Sherwoods the first and second waves reached the enemy first line fairly easily, but were scattered by the time this occurred. The third and fourth waves suffered severely in crossing from machine-gun fire. The majority of the first and second waves passed over the first-line trenches, but there is no evidence to show what happened to them there, for not a man of the battalions that reached the German second line has returned. The remaining waves … found that the enemy, who must have taken refuge in deep dugouts, had now come up and manned the parapet in parties. The Germans were noticed to be practically all bombers.... The first three waves of the 7th Sherwoods (the left of the attack) moved out to time and found the wire well cut. So far as is known, only a small proportion of these three waves reached the German second line, and after a bomb fight on both flanks, the survivors fell back on the German first line, where they found other men of the battalion consolidating. After expending all their bombs in repelling a German counter-attack, the survivors retired over the parapet.”

One can therefore say that, half an hour after the attack was launched, the Germans in the Gommecourt salient had only the 56th Division to deal with. We know that the Cemetery was seen to be occupied by our troops about nine o’clock, and it was probably shortly after this that the party of Queen’s Westminster Rifles, led by the gallant lieutenant of the Cheshires, reached the Quadrilateral. But the Germans were then masters of the situation on the north of the salient and, freed from all anxiety in that quarter, could turn their whole attention to the 56th Division. Up to this time fighting had been hard, but slow progress had been made, and with even moderate success on the part of the 46th Division, depression and bewilderment might have seized the enemy. But he turned with elation to the southern attack, and shortly after 9.30 a.m. small parties of bombers were seen moving through Gommecourt Park to attack the London Rifle Brigade, and strong attacks were launched from the east of Gommecourt village.

For the rest of the day no help came from the 46th Division, though a new attack was ordered, postponed, and postponed again. The plan was to reorganise assaulting waves from the carrying parties, and at 3.30 in the afternoon it seemed probable that an attack would materialise, but it did not. It was perhaps as well, for by that time the 56th Division occupied the German front line only, and that in very weak strength.

As night fell all became quiet. The 167th Brigade relieved the 168th on the right; the 169th reorganised.

General Hull’s conclusions on this action are that

“the primary reason for failing to retain the ground was a shortage of grenades. This shortage was due to:

(a) The enemy’s barrage, and in a lesser extent the machine-gun fire from the flanks, which prevented supplies being carried across No Man’s Land.

(b) To the breadth of No Man’s Land.

(c) Possibly to insufficient means of collecting grenades and S.A.A. from men who had become casualties, and from German stores.

I understand that our counter-battery groups engaged a very large number of German batteries—the results were not apparent, and I think this was due to the limited number of guns available, and also to the small calibre of the majority employed (60-pounders, 4·7 guns, and 4·5 howitzers). I consider it would be better to employ the heavy (9·2) and medium (6) howitzers, and even the super-heavy.

It was particularly noticeable that, once our attack was launched, the Germans attempted practically no counter-work.

The preliminary bombardment started on the 24th June, and continued for seven days. During this period the enemy seemed to have increased the number of his batteries.... The effect of the bombardment on the German trenches was very great … on the dugouts the effect was negligible. On the moral of the enemy the effect was not so great as one would have hoped....

I am doubtful of the value of these long bombardments, which give the enemy time to recognise the points selected for the attack, and possibly to relieve his troops, and to concentrate guns, and to bring up ammunition.

The intense bombardment prior to the attack lasted sixty-five minutes, considerably longer than any of the previous bombardments. I am in favour of having as many false attacks and lifts of artillery fire as possible, but consider there should be no difference....

The German attitude and moral varied considerably—some of the enemy showed fight, but other parties were quite ready to surrender as soon as they came up from their dugouts. But it cannot be said that their moral was any more shattered by the bombardment than were their dugouts. Later in the day German bombers advanced with great boldness, being assisted by men who advanced over the open. Our men appear to have had no difficulty in dealing with enemy bombers at first—it was only when bombs were scarce that the enemy succeeded in pushing us back. The counter-attacks on the right were never made in great strength, but were prepared by artillery fire which was followed up closely and boldly by bombers. On the left the enemy appeared to be in greater strength, and came out of Gommecourt village and through the Park in great numbers.”

The men of London had done well, although the salient remained in the hands of the enemy. The effort of the infantry was valiant, and they were supported with devotion by the artillery. The artillery observers took great risks, and the conduct of one of Lieut.-Col. Prechtel’s wire-cutting batteries is well worthy of note. It established itself practically in our front line, about W48, and fired 1,200 rounds during X, Y, Y1, Y2 days and on Z day fired a further 1,100 rounds.

The German plan was, as has been shown, to prevent all reinforcements from crossing No Man’s Land, and to deal with those troops who had lodged themselves in their trench system by strong and well-organised bombing attacks.

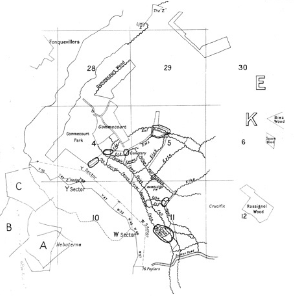

1. The Gommecourt Salient.

The dotted line is the old British line.

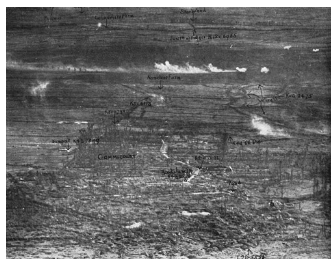

GOMMECOURT, JULY 1916

There is no doubt that the main object of the attack had been fulfilled. Unpleasant as it may seem, the rôle of the 56th Division was to induce the enemy to shoot at them with as many guns as could be gathered together, and also to prevent him from moving troops. The prisoners captured were 141 from units of the 52nd Reserve Division, and 37 from the 2nd Guards Reserve Division, so that no movement of troops had occurred on that front, and we know that the number of batteries had been increased. There were many more prisoners than this, but they were caught in their own barrage as they crossed No Man’s Land, and large numbers of dead Germans were afterwards found in that much-battered belt.