Полная версия

Harmonious Economics or The New World Order

The data provided above allows to see that the US allocates as much for healthcare and social security as for education. It is also evident that if these expenses did not pay back, they would not be so significant. The expenses for reproduction of work-force in the US in 1947—1989 alone increase 5.5 times, while those for reproduction of fixed capital – by 3.7 times only. As the UK Prime Minister Tony Blair said, “Knowledge-based economy has people as its main resource’. This idea was supported by Bill Clinton, who believed that “Sustained growth requires investment in human capital, education, healthcare, technology, infrastructure’43. However, modern Russia would rather save on its people.

Social labour productivity is highly dependent on the labour and living conditions of workers. Therefore, all measures that improve the labour ergonomics increase its productivity, as well. But one of the biggest impacts on SLP is that of the extent of people’s satisfaction: the higher it is, the more significant their contribution in the production process.

Let us consider a specific example. To keep a worker idle – like a machine – about 2 Mcal of energy is needed. If the worker consumes 3 Mcal, he can use one 1 Mcal for useful work only, that is 33% of the energy received from the food he eats. Then, if the same worker consumes 4 Mcal of food, he can use 2 Mcal for work. This shows how the increase in the amount of food eaten every day by 25% lets the worker do twice the amount of work he did before. This is why academician S. G. Strumilin concludes that “the more we want to save on economy, on income and food norms, the bigger damage we will suffer’44 [37].

Eminent entrepreneur Henry Ford believes the same: “Wages is more of a question for business than it is for labour. It is more important to business than it is to labour. Low wages will break business far more quickly than it will labour’45 [38]. Saving on people is, thus, a costly approach, however promising it may seem. That is why all unpopular measures are, in the end, regressive (sic).

SLP considerably depends on the technical equipment of labour, and this subject has often been brought up by authors. However, there is no definite answer here. In fact, machine production and maintenance require so much effort, that their use does not always help to save social labour. That is why the science that works out progressive principles, machines and technologies is believed to be one of the major production forces of the society. Plato wrote that “there is nothing more powerful than knowledge, it always and everywhere overpowers pleasure and all other things’. “Our economy is not based on natural resources, but on intelligence and application of scientific knowledge’ (Philip Handler, President of the US Academy of Sciences). And advanced economies do understand this.

As the result, American companies are the only to spend more than $15 billion on training and education of their personnel annually. For the implementation of the Equal Opportunity in Education Act adopted in the US in 2002 alone $26.5 billion was allocated. The total costs of education in advanced economies amounts to 5—6% of their GNP.

In Russia, however, they have never reached 1%, and in the years of crisis dropped further to 0.23% of the GDP. As the result, the salaries of professors employed at the Russia’s Higher education system were 1.5 times lower than the average for the country. The salaries of other academic workers are too shamefully low to quote here. Teachers in Russia do not earn enough to afford a minimal living standard. Doctors and nurses, however essential their work might be, are struggling to make both ends meet. It is evident that such stimulation neither stimulates the country’s development, nor creates proper conditions for the SLP increase or production acceleration.

Thus, the state as such, in order to assure its proper functioning, relies on quite specific expenses, just like a house or a complex piece of equipment require regular maintenance. Otherwise, they turn into a ruin. That is why a redistribution of the national income to private individuals beyond reasonable level turns out to be mortal for the country.

1.3.5. Labour differentiation and cooperation

The science of equilibrium is the key of occult science. Unbalanced forces perish in the void.

Eliphas Levi46

Still, one of the most efficient factors that increase SLP is improvement of labour organisation. It does not require as much time and money, however, it efficiency is superior to that of all other factors combined. Besides, notwithstanding all other conditions, only harmonious organisation is capable of shaping harmonious economics, and of creating conditions for the implementation of all highly-productive advances. This factor remains the backbone of any enterprise or economy restructuring. All the rest is nothing more than its result.

We are not considering here the factors related to the scientific labour organisation, such as specialization, and introduction of rational labour methods and techniques, because all of them have already been studied in great detail. This approach reduces organisation to building an optimal structure for production based on the combination of two dialectically different factors, i.e. labour differentiation and labour cooperation. Without providing an ample description of these phenomena, we will just point out some of their properties that would be interesting for the current analysis.

In the process of evolution, it has been remarked that professional labour differentiation in space and time increases significantly labour productivity. This tactic helps split human activity into specific functions and operations, none of which are meaningful on their own, by all of which when combined creating a completed product. Such organisation makes better use of the individual workers’ capacities, improves their qualification and instruments of production, and assures rational consumption of work time. As the result, among workers there are more and more experts in a narrow field of specialization.

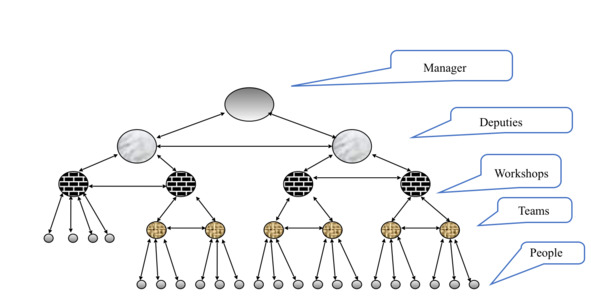

This factor influences the formation of all social organisation structures (see Figure 1). Besides, the more complex and specialized production, the deeper labour differentiation. “How far the productive forces of a nation are developed is shown most manifestly by the degree to which the division of labour has been carried’ (K. Marx and F. Engels [39]). Thus, the division of labour types according to their functions is one of the most powerful factors of progress.

On the other hand, labour differentiation leads to the need for agreement and unification of separate workers and worker groups within the common working process, for interaction of all levels of production from individual employees and teams to entire enterprises, subindustries and sectors of economy. This association and interaction between the separate specialized workers in the labour process bear the name of labour cooperation (from Latin cooperation). This phenomenon is one of the key factors of labour organisation.

Labour cooperation converts labour quantity into higher quality thanks to “the creation of a new power, namely, the collective power of masses’ (K. Marx [40]). Cooperation is followed by joining of the results of differentiated labour; as the result, labour productivity increases faster than aggregate labour consumption. It is this correlation that allows resolving global issues: developing science, education, culture, building defence from enemies, constructing canals, dams, roads, and other structures that serve a public purpose, and bring collective benefit.

Rational combination of labour differentiation and cooperation shapes all economic structures. For instance, workers unite to make a team, teams form workshops, which are parts of companies, enterprises, plants, and economic sectors.

On the other hand, the state is a cooperation of its regions, a region is a cooperation of districts, areas, etc. Thus, labour differentiation and cooperation can apply both within production framework, and depending on the territory; they function both in space and time.

In literature on economics this structure is called “organisation hierarchical tree’. Figure 2 shows such tree for a random plant. However, this structure is applicable to other types of organisations as well, including the state. In each case it is determined by a series if objective and subjective factors, by the production and organisation type, its level of development, management, production and human relations, type of property, etc.

At the same time, as it is easy to see, each link, each cell of production has both labour differentiation and labour cooperation. For instance, if we analyse the organisation tree from Figure 2, from top to bottom, we will notice the division of all structures into a number of cells. But when you move from bottom to top, then all the cells combine in cooperation to create a bigger structure. Thus, labour differentiation and labour cooperation are interdependent instruments of organisation. Labour differentiation pattern determines the reasonable level of labour cooperation. And vice versa, cooperation allows to deepen labour differentiation processes. When a worker does not have to do everything in life himself, he can specialize in his profession even more. At the same time, he would be more interested in cooperating with other workers and units.

Fig. 2. Modern enterprise “organisation tree’

This is why labour differentiation contributes to a more intense labour cooperation within professional or territorial unions. Moreover, without cooperation with other structures labour differentiation is not efficient and cannot be allowed. A metallurgist will only work well when a farmer provides him with food to eat. The same level of interdependence is observable with all other professions.

On the other hand, the impact of the above-mentioned factors on people is not uniform. Labour differentiation makes workers more egoistic, and limits their circle of interests to personal problems. Cooperation, on the contrary, makes people part of a bigger entity, more important than a single person. This elevates the man, enlarges his scope of interests including other people in it, helps understand his place in the hierarchy of the community, the society, and the entire Universe. Thus, the man becomes wiser and more far-seeing. The combination of the factors mentioned generates the variety of human characters, promotes a dialectic unity of the humanity, and integrates people within each other, within their communities and the World.

This means that no labour differentiation is possible without cooperation, just as no cooperation is feasible unless the components of the whole are divided. Every unit is created through labour differentiation of a bigger entity, and all divided labour is reunited in a bigger structure. And this does not depend on property form, on fashion, on organisation name, or nature of its activities.

Every enterprise, every organisation possesses dual qualities. On the one hand, its mission is to satisfy the needs of its employees, on the other hand, to satisfy social needs. “Capitalists and workers are equally wrong in thinking that enterprises exist for the sake of income. They disagree on who should have this income. In reality, enterprises exist for satisfying social needs’47 (H. Ford [38]).

It is evident that without social functions any enterprise loses all sense to exist, as if the workers and the owners were not interested in the results of their own labour. Absence of social functions turns organisations into business mechanisms, that is, hospitals then work for the profit of doctors, schools – for teachers, banks – for their own gain, administrative services become ordinary tools for enrichment, and armies serve the well-being of generals.

On the other hand, labour differentiation and cooperation generate additional types of work, not required before, like coordination, supply, control, accounting, and management. It would be hard to classify them as anything better than social labour waste if they did not create conditions for labour differentiation and cooperation, and did not help save social labour to a greater extent than they consume it. However, this is not always the case. In certain conditions the amount of supplementary labour is inexcusably large and its efficiency (i.e. the capacity to save social labour) derisory.

The managing and controlling structures often expand disproportionately to the actual need in them and to the results of their own work. This happens very often. That is why the problem of balance between various types of divided labour, of organisation of their cooperation, and of coming up with methods to determine the nature and the way of labour remuneration is rather complex. It will be described in greater detail in 3.1.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Примечания

1

[Translator’s note: This English-language translation of the monograph is based on the Russian-language manuscript provided by the author; it may, therefore, contain a number of slight differences from the published Russian version of the book.]

2

[Translator’s Note: Unless stated otherwise, all quotations from English-language original sources and English translations of foreign-language sources referenced in the bibliography are cited from the respective originals/ translations. All other quotations, unless stated otherwise, have been translated into English for the present edition. All biblical quotations are cited from the Authorized King James Version of the Bible.]

3

Cit. ex T. Carlyle, The Present Time (Cambridge University Press, 2013), 24.

4

[Translator’s note: Translated by me.]

5

Cit. ex J. Pine and P. Donahue, Money and Wealth: A Book of Quotations (Courier Corporation, 2013), 15.

6

Cit. ex G. B. Shaw, George Bernard Shaw: Collected Articles, Lectures, Essays and Letters (e-artnow, 2015).

7

Cit. ex A. Smith, The Wealth of Nations: Books I – III (Penguin Classics, 1987), Book I, Chapter IX.

8

Cit. ex L. McFadden, An Astounding Exposure. Congressman McFadden on the Federal Reserve Corporation. Remarks in Congress, 1934.

9

Cit. ex Matthew 6:24.

10

Cit. ex M. Kline, Mathematics and the Search for Knowledge (Oxford University Press, USA, 1985), 181.

11

Cit. ex F. Bacon, Essays, civil and moral (The Harvard Classics, 1909—14).

12

Cit. ex E. C. Stedman, ed., A Victorian Anthology, 1837—1895 (Cambridge: Riverside Press, 1895).

13

Cit. ex H. de Balzac, Gobseck (Clap Publishing, LLC., 2017), 14.

14

[Translator’s note: Translated by me.]

15

[Translator’s note: In the original, Maori ad minus, incorrect.]

16

[Translator’s note: Translated by me.]

17

Cit. ex Gh. Aurobindo, Sri Aurobindo: The Hour of God: Selections from His Writings (Sahitya Akademi, 1995), 10.

18

Cit. ex S, Mukundananda, Bhagavad Gita: The Song of God (Jagadguru Kripaluji Yog, 2013).

19

Cit. ex Satprem, Sri Aurobindo, or The Adventure of Consciousness (Mira Aditi, 2008).

20

Cit. ex C. G. Jung, Psychology and Religion Volume 11: West and East. Collected Works of C.G. Jung (Routledge, 2014), 483.

21

Cit. ex Leaves of Morya’s Garden I (The Call) (Agni Yoga Society).

22

Cit. ex H. P. Blavatsky, The Voice of Silence (Theosophical University Press Online Edition).

23

[Translator’s note: Translated by me.]

24

Cit. ex International Socialism (1st series), No. 6, Autumn 1961, 24—25. Translated by Kurt Dowson.

25

Cit. ex F. Tyutchev, The Complete Poems of Tyutchev. Translated by F. Jude (Durham, 2000).

26

[Translator’s note: The attribution of these three quotations to their authors is strongly contested.]

27

Cit. ex V. Minorsky, Sharaf al-Zamān Ṭāhir Marvazī on China, the Turks, and India; Arabic text circa AD 1120. (London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1942).

28

Cit. ex O. Spengler, The Decline of the West (Oxford University Press, 1991), 176.

29

[Translator’s note: Translated by me.]

30

[Translator’s note: Translated by me.]

31

[Translator’s note: In the original, Vie victis, incorrect].

32

Cit. ex G. K. Chesterton, The Ballad of the White Horse (Courier Corporation, 2013), 26.

33

Cit. ex S. E. Ambrose, Eisenhower: Soldier and President (Simon and Schuster, 1991)

34

Cit. ex F. Dostoevsky, A Writer’s Diary. Translated by Kenneth Lantz. Abridged edition (Northwestern University Press, Evanston, Illinois, 2009)

35

[Translator’s note: Translated by me.]

36

[Translator’s note: Cit. ex Plato, Laws. Translated by Benjamin Jowett (Cosimo Classics, New York, 2008). In the original, this quotation is attributed to Plato’s The Republic, wrongly.]

37

[Translator’s note: Translated by me.]

38

[Translator’s note: Translated by me.]

39

Cit. ex K. Marx, Marx 1857—61. Marx and Engels: Collected works, Vol. 28. Translated by Ernst Wangermann (Lawrence & Wishart, Electric Book, 2010).

40

Cit. ex K. Marx, Theories of Surplus Value in Economic Works of Karl Marx 1861—1864 (Progress Publishers, Moscow).

41

Cit. ex I. A. Krylov, Crawfish, Swan and Pike. Translated by C. Fillingham Coxwell. (Librivox recordings).

42

Cit. ex T. More, Utopia (Roubert Foulis, 1743), 39.

43

Cit. ex J. Godwin, Clintonomics: How Bill Clinton Reengineered the Reagan Revolution (AMACOM Div American Mgmt Assn, 2009), 195.

44

[Translator’s note: Translated by me.]

45

[Translator’s note: The original incorrectly references these words, the quotation is cited from Today and Tomorrow by Henry Ford (Garden City Pub. Co., 1926), 151.]

46

Cit. ex Manly P. Hall, The Secret Teachings of All Ages an Encyclopedic Outline Of Masonic, Hermetic, Qabbalistic And Rosicrucian Symbolical Philosophy Being an Interpretation of the Secret Teachings concealed within the Rituals, Allegories, and Mysteries of all Ages (H.S. Crocker Company, Incorporated, 1928).

47

[Translator’s note: Translated by me.]