Полная версия

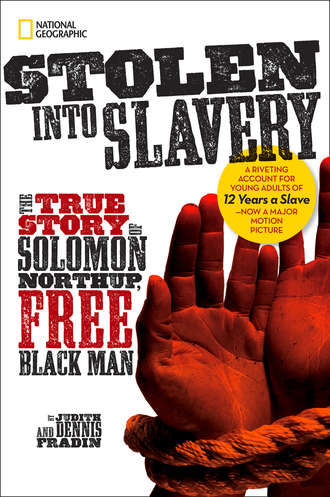

Stolen into Slavery: The True Story of Solomon Northup, Free Black Man

With gratitude to Renee Moore, the founder of Solomon Northup Day, who was a tireless resource for us. We also thank the photo archivists at the Alexandria and Baton Rouge campuses of Louisiana State University for their gracious assistance, and the family of Sue Eakin, Solomon Northup biographer extraordinaire.

For the Louisiana branch of the Fradin family—Diana Judith, Michael James, Shalom Amelia, and Dahlia Sol Richard

Text copyright © 2012 Judith Bloom Fradin and Dennis Brindell Fradin

Compilation copyright © 2012 National Geographic Society.

All rights reserved. Reproduction without written permission

from the publisher is strictly prohibited.

Dust jacket design by Eva Absher and David M. Seager

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fradin, Judith Bloom.

Stolen into slavery : the true story of Solomon Northup, free black man / by

Judy and Dennis Fradin.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-1-4263-0987-8

1. Northup, Solomon, b. 1808. 2. Slaves–United States–Biography. 3. African Americans–Biography. 4. Plantation life—Louisiana—History–19th century. 5. Slavery—Louisiana—History–19th century. I. Fradin, Dennis B. II. Title.

E444.N87F73 2012

306.3′62092–dc23

[B]

2011024664

v3.1

Version: 2017-07-07

WE FRADINS HAVE WRITTEN DOZENS OF BOOKS together. Researching and writing about the life of Solomon Northup has been both fascinating and inspiring.

Following the Civil War, many slaves wrote about their experiences. Solomon Northup’s narrative, written prior to the Civil War, is particularly gripping. Having previously lived as a free man in New York State, his enslavement seemed all the more bitter. His desire to escape fueled his determination to survive. Solomon drew strength and solace from his music, which allowed him a temporary refuge from his seemingly endless years in Louisiana cane and cotton fields.

Soon after he returned to his wife and family, Northup published his autobiography, Twelve Years a Slave. That book was the source of much of the detail and all of the dialogue in Stolen Into Slavery. Solomon Northup’s memoir, co-authored with David Wilson, reflects not only Northup’s memory of his experiences but also his deepest feelings about them.

Of course, memory can be tricky. Therefore we verified the basic events of Solomon’s life in bills of sale and in court records. But it is Solomon’s interpretation of events that gives us a unique glimpse into that most “peculiar institution,” American slavery.

—Judith and Dennis Fradin

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Note from the Authors

CHAPTER 1 “Well, My Boy, How Do You Feel Now?”

CHAPTER 2 “I Wished for Wings”

CHAPTER 3 “I Will Learn You Your Name!”

CHAPTER 4 Life Is Dear to Every Living Thing

CHAPTER 5 “A Song of Peace”

CHAPTER 6 “If I Ever Catch You With a Book”

CHAPTER 7 “I Am Here Now a Slave”

CHAPTER 8 “How Can I End My Days Here?”

CHAPTER 9 “Solomon Northup Is My Name!”

CHAPTER 10 “I Had Been Restored to Happiness and Liberty”

Afterword

Time Line

Bibliography

Online Resources

Illustration Credits

SOLOMON NORTHUP AWOKE IN THE MIDDLE OF AN April night in 1841 with his body trembling, his head throbbing, and a terrifying question in his mind: Where was he? He slowly realized that he was in a dark, dank, foul-smelling dungeon in Washington, D.C. Worse yet, he was in handcuffs and his feet were chained to the floor.

As his head cleared, Solomon managed to slip a hand into his trousers pocket, where he had placed his money and his “free papers” for safekeeping. They were gone! He checked his other pockets and found no trace of the money or the papers that proved he was one of 400,000 “free blacks” in a nation where 2.5 million African Americans were slaves.

“There must have been some mistake,” Solomon told himself. Any second now the two white men he had been traveling with would arrive to free him. But as the night wore on, he began to wonder whether these seemingly friendly men could have betrayed him.

The rising sun revealed that Solomon was in a cell with only one small window covered by thick iron bars. Soon he heard footsteps coming down the stairs. A key turned in a lock, the heavy iron door swung open, and two men entered the room where Solomon was chained.

“Well, my boy, how do you feel now?” asked one of the men, who Solomon later learned was named James Birch.

Solomon, who was 32 years old, wasn’t accustomed to being called “boy,” which was a demeaning way of addressing male slaves regardless of age. “What is the cause of my imprisonment?” Solomon demanded.

“I have bought you, and you are my slave,” said Birch, adding that he planned to send him far south to New Orleans to be sold.

“I am a free man, a resident of Saratoga Springs, New York, where I have a wife and children who are also free, and my name is Northup!” Solomon protested. Furthermore, he vowed, once he was liberated from this hellhole he would prosecute Birch for kidnapping.

Birch was enraged. He called Solomon a “black liar” and insisted that he was a runaway slave from Georgia. As Solomon continued to assert that he was a free black man from New York, Birch ordered his assistant to bring him his paddle and whip. Ripping off Solomon’s shirt, the assistant stood on his chains to pin him to the floor while Birch beat him with the paddle. From time to time Birch paused to ask whether Solomon still claimed that he had been free. Despite the intense pain, Solomon refused to say that he was a slave.

When the paddle broke, Birch picked up his whip. Soon streams of blood were pouring down Solomon’s back, and strips of skin were gouged out wherever the lash struck. Even so, Solomon still wouldn’t say what Birch demanded—that he was a fugitive slave from Georgia.

After a quarter of an hour Solomon was barely conscious and Birch’s right arm was exhausted. As he put down his whip, Birch warned Solomon, “If you ever utter again that you are entitled to your freedom or that you have been kidnapped, the punishment you have just received is nothing compared with what will follow!” Birch and his assistant then departed, slamming the big iron door behind them.

Paddling was one of many methods used by owners to humiliate and control their slaves. This scene is set in the West Indies, but Solomon Northup suffered the same punishment in Washington, D.C. (Illustration Credits 1.3)

Solomon had been beaten so savagely that for a few days he expected to die. His handcuffs and leg chains were removed but the pain from his injuries made movement difficult. His only contact with the outside world came twice a day when the assistant brought him a tin plate containing a piece of fried pork, a slice of bread, and a cup of water.

When he had healed enough to walk, he was allowed to exercise in the yard with several other black prisoners in the building. One man whom he befriended, Clemens Ray, informed him that they were in a “slave pen”—a kind of prison where James Birch held his slaves before sending them down to New Orleans to be sold. The slave pen was so close to the U.S. Capitol that Solomon could see the building’s dome from the yard.

This slave pen is similar to the one in which Solomon Northup was held. Each door led to a dark, airless cell. (Illustration Credits 1.4)

Heartsick and furious about being enslaved, Solomon enjoyed peace of mind only when he went to sleep at night. Then he would dream that he was back in Saratoga Springs with his wife and their three children. But he always awakened to the realization that he was imprisoned in a jail cell in Washington, D.C., and, in the darkness, he would weep bitter tears.

Yet he did have one hope: escape! Fleeing from the slave pen was pretty much out of the question because the building was like a fortress and was surrounded by a tall, brick wall. But perhaps the trip to New Orleans would offer an opportunity to break free from this nightmare.

ALL 13 AMERICAN COLONIES ALLOWED SLAVERY DURING the 1600s and 1700s. Not until 1780—four years after the colonies declared themselves to be the United States of America—did Pennsylvania become the first state to outlaw slavery. Other northern states also made slavery illegal, but some took their time doing so. Solomon Northup’s home state, New York, didn’t outlaw slavery until 1827.

The black mother’s status determined that of her children in the slave states. If the mother was a slave, her children were, too. If the mother was a free black, so were her children.

Solomon Northup was born in Minerva, New York, 100 miles south of the Canadian border and 200 miles north of New York City. Solomon claimed that he had entered the world “in the month of July, 1808.” Since Solomon’s mother was a free black woman, he was born free.

On his father’s side, Solomon’s ancestors had been slaves belonging to a white family named Northup. Around the year 1800 Solomon’s father, Mintus, had been freed by the terms of his owner’s will. Mintus had adopted the last name Northup to honor the family that had liberated him.

Solomon was a serious, hardworking child. When he wasn’t helping around the family farm, he loved to read. His favorite pastime, however, was playing the violin. By his teens Solomon was so skillful a fiddler that friends and neighbors hired him to perform at dances and parties.

On Christmas Day of 1829, 21-year-old Solomon Northup married Anne Hampton. Solomon liked to say that the blood of three races flowed through Anne’s veins: Native American, white, and black. The couple had three children—daughters Elizabeth and Margaret and a son, Alonzo.

In the spring of 1834 Solomon and his family settled in Saratoga Springs, a vacation resort 30 miles from Albany, the capital of New York. During the warm months when tourists flocked to Saratoga Springs to bathe in its mineral spring waters, Solomon drove a carriage for the hotels. At other times he worked as a carpenter, helping to build area railroads. In addition, Solomon earned an income from playing his violin. Meanwhile, Anne found employment as a cook in hotels and inns. By pinching pennies, Solomon and Anne managed to squeak by financially. Around Saratoga Springs, the Northups had a reputation for being a close and loving family.

One morning in late March of 1841 Solomon went for a walk in hope of finding an odd job. At the time, Anne was 20 miles away working as a cook at Sherrill’s Coffee House in Sandy Hill, now known as Hudson Falls, for a few weeks. Anne had taken nine-year-old Elizabeth with her. Seven-year-old Margaret and five-year-old Alonzo were being cared for by an aunt in or near Saratoga Springs.

At the corner of Congress and Broadway, Solomon spied an acquaintance of his talking to two white strangers. “Solomon is an expert player on the violin,” his acquaintance explained, while introducing him to the two men. The strangers, who said their names were Merrill Brown and Abram Hamilton, claimed to be in need of a violinist. They were headed to Washington, D.C., to meet the circus they worked for—or so they said—and a violinist would attract customers to the small shows they would present along the way. Brown and Hamilton offered to pay Solomon a dollar a day for driving them in their carriage as far as New York City, plus three dollars for each performance and enough money for his return to Saratoga Springs.

Before he was kidnapped into slavery, Solomon drove a carriage like those waiting in front of the United States Hotel in Saratoga Springs, New York, in this early 20th-century photo. (Illustration Credits 1.6)

Excited by the prospect of a windfall, Solomon hurried home and grabbed a suitcase, a few clothes, and his violin. Since he expected to be back home before Anne’s return, he didn’t even stop to leave his wife a note about where he was going. Solomon climbed into the driver’s seat of Brown and Hamilton’s carriage and drove away from Saratoga Springs as happy as he had ever been in his life.

Thirty miles into their journey, they stopped to present a show in Albany. Hamilton sold the tickets, Solomon provided violin music, and Brown amused the audience by juggling balls, walking on a tightrope, and making invisible pigs squeal. This proved to be their only performance en route to New York City, for Brown and Hamilton said they were worried that they wouldn’t reach Washington in time to join up with the main body of the circus.

Once in New York City Solomon expected to be paid and then return home to Saratoga Springs. However, Brown and Hamilton had another exciting proposal. They promised that if Solomon continued with them to Washington, D.C., the circus would hire him for a more permanent job. Touring with the big show for a few weeks, he would earn more money than he made in an entire year in Saratoga Springs.

Solomon accepted the offer. His family could use the money. Besides, he trusted Brown and Hamilton, who seemed to be concerned for his welfare. For example, before leaving New York City they took Solomon to a government office to obtain free papers for him. That way if someone in Washington claimed he was a slave, Solomon could present written proof that he was free. This was important because slavery was legal in Washington, D.C. Any black person in our nation’s capital risked being mistaken for a slave.

When they reached Baltimore, Maryland, Solomon parked the carriage. He and his two new friends boarded a train. With his free papers securely in his pocket, Solomon arrived in the U.S. capital with Brown and Hamilton on April 6, 1841. They checked in at Gadsby’s, the city’s top hotel, on Pennsylvania Avenue down the street from the White House.

Solomon Northup spent the first 32 years of his life a free man in upstate New York. He was then lured to Washington, D.C., where he was sold into slavery. (Illustration Credits 1.7)

Solomon and his companions arrived in the national capital at a time of mourning. Two days earlier President William Henry Harrison had died in the White House after being in office for only 30 days, making Vice President John Tyler the new President. After supper Brown and Hamilton invited Solomon to their room, where they counted out $43 and handed it to him. That was more than he was due, but the two circus men insisted that he take a few extra dollars because it wasn’t his fault that they had presented fewer performances than expected on the way to Washington. They invited Solomon to attend President Harrison’s funeral procession with them the next day. Afterward, they promised, they would introduce Solomon to the circus company owners.

The next day, April 7, a giant funeral honoring the late President was held in Washington. Bells were tolled, cannons were fired, and thousands of people joined the procession on foot and in carriages. Several times during the ceremony Brown and Hamilton invited Solomon to join them for drinks in a nearby saloon. Unaccustomed to liquor, Solomon was soon drunk. While he wasn’t looking, either Brown or Hamilton placed a drug in his drink to make him even drowsier. More than a century later doctors at Tulane University Medical School in New Orleans concluded that Solomon was drugged with belladonna or laudanum, or with a mixture of both potent drugs.

When Solomon returned to Gadsby’s Hotel, his head began to hurt, and he felt sick to his stomach. He lay down, but his head ached too much for him to sleep. Solomon slipped into a delirium. In the dead of night several people entered his room—he thought Hamilton and Brown were among them—who said they were taking him to a doctor. Staggering through the streets, Solomon was led into a building, where he lost consciousness. Instead of coming to in a doctor’s office, however, he awoke in the slave trader James Birch’s slave pen.

Locked in his cell most of each day, Solomon had plenty of time to think. Looking back, he realized that from the morning he had met Brown and Hamilton in Saratoga Springs, the men had tried to win his confidence. They had lured him farther and farther south by convincing him that the circus offered plenty of easy money. By insisting that he obtain his free papers, they had created the illusion that they cared about his welfare. The truth was, there was no fortune to be made working for the circus. In fact, there was no circus. The whole thing had been a scheme to sell him as a slave to Birch.

What about Birch? Had he known he was buying a free man? Solomon was certain of it. But buying a free man was illegal. If it became known that Solomon was no slave, Birch would have to let him go, losing his entire investment. Birch might even be sent to prison for enslaving a black man he knew to be free. Birch had beaten Solomon savagely for claiming to be free so that he would keep quiet about it in the future.

Solomon had learned something from that beating: If he wanted to survive, he couldn’t talk about being free anymore. His wisest course was to keep his eyes open for a chance to escape and to try to send word home that he had been kidnapped.

Two weeks after Solomon arrived in the slave pen, Birch and his assistant entered his cell late one night, carrying lanterns. They woke him up and ordered him to prepare to depart. Before being led outside, Solomon and four of Birch’s other slaves—Clemens Ray, a young woman named Eliza, and Eliza’s young daughter Emily and son Randall—were handcuffed together. As they were marched through Washington, Solomon thought about calling out for help. But the streets were practically deserted, and in a city where buying and selling slaves was legal, who would pay attention to a black man’s claim that he had been kidnapped? He thought of trying to run away, but how far could he get with his left hand cuffed to Clem Ray’s right hand?

Birch led the five slaves to the Potomac River, where he ordered them into the hold of a steamboat, among boxes and barrels of freight. The vessel was soon steaming down the Potomac. When it passed George Washington’s tomb at Mount Vernon, the steamer tolled its bell in honor of the Father of His Country. Now that he was a slave Solomon saw things differently. It seemed odd to him that the same people who practically worshiped George Washington for winning his country’s freedom thought nothing of denying slaves theirs.

In the morning Birch allowed his slaves onto the steamer’s deck to eat breakfast. Some birds flying along the shore caught Solomon’s eye. “I envied them,” he later recalled. “I wished for wings like them.”

After a two-day journey via steamboat, stagecoach, and train, Birch and his slaves arrived in Richmond, the capital of Virginia. There Birch brought Solomon, Clem, Eliza, and her two children to a slave pen operated by a Mr. Goodin.

Goodin examined the five captives. When it was Solomon’s turn, Goodin felt his muscles. He also inspected his teeth and skin, as if considering the purchase of a racehorse. “Well, boy, where did you come from?” Goodin asked, after finishing his examination of Solomon.

Without stopping to recall Birch’s insistence that he was a runaway slave from Georgia, Solomon answered, “From New York.”

“New York!” said Goodin, aware that it was a state where many free blacks lived. “Hell, what have you been doing up there?”

When up for sale, slaves had to act agreeable while having their muscles and teeth inspected. Failure to do so could result in a whipping. (Illustration Credits 1.8)

Birch looked like he was about to kill him, so Solomon quickly explained that he had just been visiting New York. This seemed to satisfy Birch. For some unknown reason, Birch decided to keep Clemens Ray, whom he later took back to Washington with him.

Solomon spent only one day in Goodin’s slave pen. Just as Brown and Hamilton had sold Solomon to Birch in Washington, Goodin planned to send him farther south for sale at an even higher price. The next afternoon Solomon and 40 other slaves, including Eliza and her two children, were marched onto the Orleans, a sailing vessel bound for New Orleans, Louisiana.

The Orleans floated down the James River, entered the Chesapeake Bay, then worked its way into the open waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Having studied geography, Solomon had a much better idea of their course than the other slaves did. They were heading down the East Coast, intending to reach New Orleans by sailing west around Florida.

The Orleans was manned only by its captain and a crew of six. They needed help with the shipboard tasks, so the slaves’ handcuffs were removed and each of them was assigned a job, such as cleaning the vessel or waiting on the crew. Solomon headed the cooking unit and organized the distribution of food and water.

Off the coast of Florida the Orleans was battered by a violent storm that placed the ship in danger of sinking. Hoping to keep the vessel afloat, the captain sought shelter in the islands of the Bahamas. There, while they awaited a favorable wind to continue their journey, Solomon decided that the time had come to make a bold strike for freedom. He was by nature a gentle man, and the prospect of killing members of the ship’s crew repulsed him, but he knew that he might have to do so if he ever expected to be free.