Полная версия

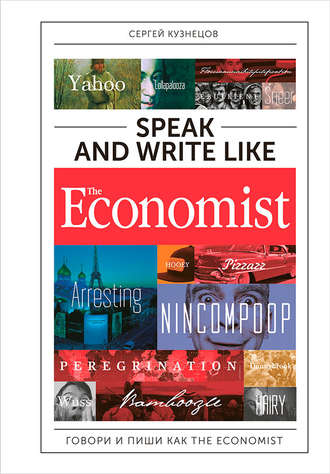

Speak and Write like The Economist: Говори и пиши как The Eсonomist

When asked why he robbed banks, Willie Sutton, a prolific bank robber (pictured, after he retired), is said to have replied: "Because that's where the money is." Sutton reportedly pinched $2m during a lifetime of crime.

The phenomenon has been described as the Wimbledon effect: Britain provides the beautiful arena where foreign champions come and beat the hell out of British players. The annual Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race is much the same: a slugfest between predominantly non-British mercenaries.

The real money is where the pain is.

The human animal is a beast that must die. If he's got money, he buys and buys and buys everything he can, in the crazy hope one of those thing.

"Corruption is rampant at high levels, and at low levels," said an FBI agent, before adding: "and all levels in between".

Foreign remittances continue to grow. In all, 250m migrant workers will send home $500 billion this year – up from $410 billion in 2012. At their destination savings often end up under the mattress – rather than channelled into microfinance schemes, for instance, as many development experts have long hoped. The marriage between remittances and microfinance has not happened yet.

"Republican gluttons of privilege" who had "stuck a pitchfork in the farmer's back".

He spent his entire career within the DeBeers stable.

It takes pride in sticking to its companies through thick and thin.

The distinction between being a successful tycoon and being an enemy of the people has been blurred.

Marriott likes to buy to the sound of cannons and sell to the sound of violins.

40 % of Missourians would oppose a new tax even if it was being used "to construct the landing pad for the second coming of Christ".

Once upon a time the overstressed executive bellowing orders into a telephone, cancelling meetings, staying late at the office and dying of a heart attack was a stereotype of modernity. Cardiac arrest – and, indeed, early death from any cause – is the prerogative of underlings. The best medicine, then, is promotion. Prosper, and live long.

Narcissism index indicators of CEO: prominence of the boss's photo in the annual report, company press releases. Length of his Who is Who entry, frequency of his use of the first singular interviews, ratios of cash compensation to second-highest paid exec.

Of course, successfully picking the leader of a big public company has always been tricky, because the job requires at least two quite different skills. Like the fox, a chief executive must know lots of little things, must manage successfully the key day-to-day aspects of the business. But like the hedgehog, he must also know one big thing: every three or four years, he will have to take a substantial strategic decision, which may mortally wound the business, if he gets it wrong. Plenty of giants, such as Cable & Wireless and AT&T, have had leaders who passed the fox test but failed the hedgehog one.

The Chinese dragon's coils encircling the world are getting tighter by the day.

In business, as in photography, it pays to stay focused.

The number of people in the United States living in poverty increased last year to 39.8 million – the highest percentage of the population in 11 years, the Census Bureau said Thursday. The number equals 13.2 percent of the country's population and is 2.5 million more than were living in poverty in 2007, which is defined by the agency as a person making less than $10,991 or a family of four making less than $22,025.

This new elite is not just a breed apart. It lives apart, in bubbles such as Manhattan south of 96th Street (where the proportion of adults with college degrees rose from 16 % in 1960 to 60 % in 2000) and a small number of "SuperZips", neighbourhoods where wealth and educational attainment are highly concentrated. These neighbourhoods are whiter and more Asian than the rest of America. They have less crime and more stable families. They are not, pace Mr Gingrich, necessarily "liberal": plenty of SuperZips voted Republican in 2004. But they are indeed out of touch.

The have-a-nice-day stuff of Walmart in Germany went down like a lead Zeppelin with employees and shoppers alike.

Hopkins was the most flamboyant advertising genius of the early 20th century – the man who convinced millions of women to buy Palmolive soap on the basis that Cleopatra had washed with it, and got the world talking about puffed wheat with the claim that it was "shot from guns" until the grains puffed to eight times their normal size.

Every company starts out as a shell. Just £ 349 ($560) buys you a company in the Seychelles, with no local taxation, no public disclosure of directors or shareholders and no requirement to file accounts. Prices rise to £ 5,000 for more sophisticated corporate structures in places like Switzerland and Luxembourg. Two firms handle two-thirds of all Delaware companies: CT Corporation (part of Wolters Kluwer of the Netherlands) and CSC.

There is no limit to human ingenuity in finding new ways to go bust.

Before the crisis many central bankers believed that all they needed was a "hammer" (interest rates) to strike a "monetary nail" (consumer-price inflation). But not every problem is a nail. Policymakers also need a full set of "macroprudential" tools, from wrenches to duct tape E.

Mr Murray starts by lamenting the isolation of a new upper class, which he defines as the most successful 5 % of adults (plus their spouses) working in managerial positions, the professions or the senior media. These people are not only rich but also exceptionally clever, because America has become expert at sending its brightest to the same elite universities, where they intermarry and confer on their offspring not just wealth but also a cognitive advantage that gives this class terrific staying power.

The best time to invest is when there is blood in the streets.

In the 19th century Alexis de Tocqueville marvelled that in America the opulent did not stand aloof from the people. A great cultural gap separates the elite from other Americans. They seldom watch "Oprah" or "Judge Judy" all the way through. In fact they do not watch much television at all. They eat in restaurants, but not often at Applebee's, Denny's or Waffle House, chains that cater to the common taste. They may take The Economist, with the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and perhaps the New Yorker or Rolling Stone. They drink wine and boutique beers (and can discuss them expertly) but only in moderation, and they hardly ever smoke cigarettes.

Mr Icahn had expounded his theory of the moronisation of American management. The typical chief executive, he said, to chuckles, is "the guy you knew in college, the fraternity president – not too bright, back-slapping, but a survivor, politically astute, a nice guy". To be a chief executive, you need to know how not to tread on anyone's toes on the way up. You eventually become the number two, who "has got to be a little worse than the number one to survive". When the number two becomes chief executive, he promotes someone a little worse than him as his second-in-command. "It is the survival of the unfittest," concluded Mr Icahn. "Eventually we are all going to be run by morons."

Most students of taxation know the advice that Jean-Baptiste Colbert, treasurer to Louis XIV, offered the beleaguered taxman: pluck the goose so as to get the most feathers with the least hissing. But suppose the goose is housed on one farm, eats the birdseed scattered in a second, and lays its eggs in a third. Which farmer gets the plumage?

History offers perhaps only one true example of a reserve-currency shift, from the British pound to the dollar. The pound was king during the era of the gold standard. But in the years after 1914, Britain switched from net creditor to net debtor, and by the 1920s the dollar was the only currency convertible to gold (although the pound returned to gold in 1925). Two costly wars and two episodes of currency devaluation in Britain later, the dollar was unchallenged as the world's chief reserve currency.

Americans used to believe that their constitution protected private property. The Fifth Amendment allows the state to seize it only for "public use", and so long as "just compensation" is paid. "Public use" has traditionally been taken to mean something like a public highway. Roads would obviously be much harder to build if a single homeowner could hold out forever or for excessive compensation. The government's powers of "eminent domain" have also been used to clean up "blighted" slums. "Urban renewal", he noted, has sometimes been nicknamed "negro removal".

The "triangular trade" as it was known, whereby slave-ships left European ports for west Africa with rum, guns, textiles and other goods to exchange for slaves, and then transported them across the Atlantic to sell to plantation-owners, and then returned with sugar and coffee, also fuelled the first great wave of economic globalisation. Slavers in France would send their shirts to be washed in the streams of the Caribbean isle of St Domingue, now Haiti; the water there was said to whiten the linen better than any European stream.

The price of used furniture is nothing but a viewpoint, and if you wouldn't understand the viewpoint is impossible to understand the price. With used furniture you can't be emotional 49.

There is almost no house property in London that is not overburdened with a number of middlemen.

Although Britons are cross about high pay, few seek capitalism's overthrow: they dislike corporate fat cats for being fat, not for being cats.

Some firms are employing a "China + 1" strategy, opening just one factory in another country to test the waters and provide a back-up. if China's currency and shipping costs were to rise by 5 % annually and wages were to go up by 30 % a year, by 2015 it would be just as cheap to make things in North America as to make them in China and ship them there.

Mr Rao offered two deals on loose coffee beans: 33 % extra free or 33 % off the price. The discount is by far the better proposition, but the supposedly clever students viewed them as equivalent. Even well-educated shoppers are easily foxed.

If not in coin you must pay in humiliation of spirit for every benefit received at the hands of philanthropy.

When Deng Xiaoping, China's paramount leader, died in 1997 his only post was chairman of the China Bridge Association.

Shopping with coupons and jars of loose change. Watering down milk to make it go further. Using washing up liquid instead of shampoo. Inventing excuses for skipping lunch. Having to walk everywhere. Sharing beds and baths. Mending clothes that are themselves second-hand. Reviving old newspapers as makeshift lampshades. Always being tired – poverty in austerity.

The first is that entrepreneurs routinely see opportunities where everyone else sees problems. A surprising number of great companies were born out of fury and frustration.

When Wal-Mart tried to impose alien rules on its German staff – such as compulsory smiling and a ban on affairs with co-workers – it touched off a guerilla war that ended only when the supermarket chain announced it was pulling out of Germany in 2006.

When things went wrong for Middle Eastern tribes a couple of millennia ago, the accepted remedy was to send a sacrificial goat out into the wilderness to placate the gods. The practice continues today, but the voters have replaced the gods, and highly paid businesspeople the goats.

Why do Americans spend such huge amounts of time, money, water, fertiliser and fuel on growing a useless smooth expanse of grass? Much better to cultivate something useful, like tomatoes.

Walmart did not become a $200 billion company without running down a few pedestrians.

Water flows towards money.

The recovery has resembled third-world traffic, where juggernauts and rickshaws, cars and cycles ply the same lanes at different speeds, often getting in each other's way.

Shoppers have been able to buy from out-of-state merchants since Sears issued its first mail-order catalogues in the 19th century.

Warren Buffett: "It's only when the tide goes out that you learn who's been swimming naked."

The new strategy looks more promising, but as always success will depend on implementation.

Consider an imaginary Englishman's day. He wakes in his cottage near Dover, ready to commute to London. Chomping a bowl of Weetabix, a British breakfast cereal resembling (tasty) cardboard, he makes a cup of tea. His privatised water comes from Veolia and his electricity from EDF (both French firms). Thumps at the gate tell him another arm of Veolia is emptying his bins. He takes the new high-speed train to London: it is part-owned by the French firm Keolis, while the tracks belong to Canadian pension funds. At St Pancras station, a choice of double-decker buses awaits. In the last couple of years, one of the big London bus companies was bought by Netherlands Railways. A second went to Deutsche Bahn, the German railway company. In March, a third was taken over by RATP, the Paris public-transport authority (its previous owners were also French). The Dutch railways logo is emblazoned on buses across London. Thanks to RATP's logo, a stylised image of the River Seine now adorns hundreds more: most Londoners neither know nor care. As for Weetabix, a French billionaire is interested in buying the firm, according to press reports. Yet Britain still feels British.

Polaroid, whose once-iconic instant-photo firm, has only one significant asset now – its name.

In a diatribe against the Rothschilds, Heinrich Heine, a German poet, fumed that money "is more fluid than water and less steady than air".

New boss didn't magic away the problems.

Most state-owned companies are prone to over-staffing, underinvestment, political interference and corruption.

Putting business at the heart of the health-care system is not a must but a bug.

The word "company" is derived from the Latin words "cum" and "pane" meaning "breaking bread together".

The sheer size of the Al Saud clan has also helped cement the nation. There have been eight generations of Saudi rulers, dating back to 18th-century sheikhs who held sway in a few oasis towns near present-day Riyadh. Many have been prolific. King Abdul Aziz himself sired some 36 sons and even more daughters. The first son to succeed him, King Saud, fathered 107 children. King Abdullah is believed to have 20 daughters and 14 sons. The extended Al Saud family is now thought to number some 30,000, though only 7,000 or so are princes. Of these, only around 500 are in government, and only perhaps 60 carry real weight in decision-making.

There's no exaggerating China's hunger for commodities. The country accounts for about a fifth of the world's population, yet it gobbles up more than half of the world's pork, half of its cement, a third of its steel and over a quarter of its aluminium. It is spending 35 times as much on imports of soya beans and crude oil as it did in 1999, and 23 times as much importing copper – indeed, China has swallowed over four-fifths of the increase in the world's copper supply since 2000.

The world knows what it wants, but cannot agree on how to get what it wants.

The financial results of Chinese companies that global investors wish to buy into can be as unintelligible as the dialect spoken in the company town. It is said (with apparent sincerity) that some Chinese firms keep several sets of books – one for the government, one for company records, one for foreigners and one to report what is actually going on.

Nokia must still work to keep its chin above the waves.

The problem is that as soon as fun becomes part of a corporate strategy it ceases to be fun and becomes its opposite – at best an empty shell and at worst a tiresome imposition.

Roads, railways, water and gas mains, sewage pipes and electricity cables all move things around. So do the blood vessels of animals and the sap-carrying xylem and phloem of plants.

Beekeeping is one example beloved by economic theorists. Bees create honey, which can be sold on the market. But they also pollinate nearby apple trees, a useful service that is not purchased or priced.

The story of Ireland is like a fairy tale: from rags to riches and back to rags again.

The full-blooded, unapologetic pursuit of America's national interest.

The rich world is in the middle of a management revolution, from "motivation 2.0" to "motivation 3.0" (1.0 in this schema was prehistoric times, when people were motivated mainly by the fear of being eaten by wild animals).

Then there is "gladvertising" and "sadvertising", a rather sinister-sounding idea in which billboards with embedded cameras, linked to face-tracking software, detect the mood of each consumer who passes by, and change the advertising on display to suit it. The technology matches movements of the eyes and mouth to six expression patterns corresponding to happiness, anger, sadness, fear, surprise and disgust. An unhappy-looking person might be rewarded with ads for a sun-drenched beach or a luscious chocolate bar while those wearing an anxious frown might be reassured (some might say exploited) with an ad for insurance.

Romantics say that the bank used to prosper by deliberately not having any strategy at all.

China's leaders hew to Deng Xiaoping's dictum that "China should adopt a low profile and never take the lead." China can hide its national demands behind a multilateral façade.

PepsiCo announced that it had developed the world's first bottle to be made entirely of a plastic consisting of plant-based materials, which can be fully recycled. Its "green bottle" is composed of switch grass, pine bark and corn husk. Pepsi hopes to produce bottles in the future using orange and potato peels and other by-products from food.

Saudi oil costs just $2 a barrel to produce, a small fraction of what it costs to extract the stuff in Alaska, say, or the North Sea. Demand from both Asia and America remains strong. Saudi Aramco, the giant state oil monopoly, is ramping up its production capacity. Having remained static at around 10m barrels per day for a generation, this is currently pushing 11m and may reach 12.5m by 2009 and perhaps 15m by 2015. Assuming a middle-of-the-range price of around $40 a barrel, the oil bubbling out of the ground could continue to be worth around $500m a day for many years to come. Oil exports, having bottomed out in 1998 at $35 billion, have since soared, hitting a record $160 billion in 2005. Last year's current-account surplus was close to $100 billion and the central bank's net foreign reserves rose to $135 billion, a jump of $90 billion in just three years.

A firm and an industry that had become accustomed to obscurity will have to get used to the limelight.

Mr Hayward set out to replace flash and fluff with nuts and bolts.

London, once a blue-blooded cocoon.

Сhina is quite open to yarn, but not jerseys, diamonds, but not jewelry.

Public transport in Los Angeles has a great future, and always will.

Mr Toyoda had been reading "How the Mighty Fall", a book by Jim Collins, an American management guru. In it, Mr Collins (best known for an earlier, more upbeat work, "Good to Great") describes the five stages through which a proud and thriving company passes on its way to becoming a basket-case. First comes hubris born of success; second, the undisciplined pursuit of more; third, denial of risk and peril; fourth, grasping for salvation; and last, capitulation to irrelevance or death.

There are lots of other jobs that aren't real. Designing a new plastic soapbox, making pokerwork jokes for public-houses, writing advertising slogans, being an MP, talking to UNESCO conferences. But the money's real work.

In theory, the case for joint ventures was compelling. The foreign partner provided capital, knowledge, access to international markets and jobs. The Chinese partner provided access to cheap labour, local regulatory knowledge and access to what used to be a relatively unimportant domestic market. The Chinese government protected swathes of the economy from acquisitions, but provided land, tax breaks and at least the appearance of a welcome to attract investment. "For a joint venture to be successful," says Jonathan Woetzel of McKinsey, a consultancy, "you have to plan for it to die".

He was waltzing from job to job.

China is full of small and medium-sized companies that have fingers in many pies, taking advantage of opportunities as they arise.

In Britain there's London, London and London. In America there are scores of hubs.

The food stamps participation has soared since the recession began). By April 2010 it had reached almost 45m, or one in seven Americans. The cost, naturally, has soared too, from $35 billion in 2008 to $65 billion last year. Only those with incomes of 130 % of the poverty level or less are eligible for them. The amount each person receives depends on their income, assets and family size, but the average benefit is $133 a month and the maximum, for an individual with no income at all, is $200. Those sums are due to fall soon, when a temporary boost expires. Even the current package is meagre. Melissa Nieves, a recipient in New York, says she compares costs at five different supermarkets, assiduously collects coupons, eats mainly cheap, starchy foods, and still runs out of money a week or ten days before the end of the month.

Business people are fond of accusing business academics of being all mouth and no trousers (if the accusers are British) or all hat and no cattle (if they are Texan).

The ultimatum they received from euro-zone leaders at the G20 summit in Cannes to reform their economies – or else.

In a country where oil cash still enhances the allure of office, can only spell turbulent times ahead.

In 1500 Europe's future imperial powers controlled 10 % of the world's territories and generated just over 40 % of its wealth. By 1913, at the height of empire, the West controlled almost 60 % of the territories, which together generated almost 80 % of the wealth.

In Central Asia the most successful companies are sinecures of nepotism.

Insurance is banking's boring cousin: it lacks the glamour, the sky-high bonuses and the ever-present whiff of danger.

Fill up an SUV's fuel tank with ethanol and you have used enough maize to feed a person for a year.

Foundations were laid timber by timber, railway sleeper by railway sleeper.

Germany's hyperinflation in 1923 – it became cheaper to burn banknotes than to buy fuel.

Corruption is often blamed on plata o plomo – meaning silver or lead, bribes or threats.

Global business has been rocked by crises, from Enron to the financial meltdown. Harvard Business School (HBS), alas, played a role. Enron was stuffed with HBS old boys, from the chief executive, Jeff Skilling, downward. The school wrote a sheaf of laudatory case studies about the company. Many of the bankers who recently mugged the world's taxpayers were HBS men.

Hayward is in the meat grinder of public opprobrium along with Lloyd Blankfein, chief executive of Goldman Sachs, and Akio Toyoda, president of Toyota.

Contrary to popular belief, traffic in Atlanta is not always hellish. There are a good few days each year when it is merely purgatorial.

Consumer spending accounts for about 70 % of U.S. economic activity.

Sin taxes have a long history as a fiscal wheeze: Parliament first introduced levies on beer and meat in 1643 to finance its fight against the Crown. Levies on alcohol have persisted: tax is now around 53p on a pint of beer, £ 2.18 per bottle of wine and £ 8.54 on a bottle of whisky. Tobacco was originally taxed as an imported luxury; today, duty on cigarettes accounts for about three-quarters of the price of a packet of cigarettes. Laziness is a harder sin to target, but one weapon against it is fuel duty: 23 % of car journeys are of less than two miles, so walking or cycling are reasonable alternatives for at least some trips. Fuel taxes also target a greater ill – the exhaust fumes that contribute to global warming. Tax, including VAT, accounts for 63 % of the price of petrol.

As the old saw has it, they tax neither you nor me but the man behind the tree.

Brazil's brief recession of 2009 was a fall onto a trampoline.

Several other countries show evidence of what might be dubbed the "DOG factor": a discount for obnoxious governments. Iran, like Russia a target of Western sanctions, trades on a p/e of just 5.6 and has a total stockmarket value of $131 billion; were it to be rated on a par with the average emerging market, its market value would be $292 billion, so its DOG factor is $161 billion or 55 %. One trillion dollars. That may be the cost to Russian investors of Vladimir Putin's rule. It is the equivalent of about $7,000 for every Russian citizen. The calculation stems from the fact that investors regard Russian assets with suspicion. As a result, Russian stocks trade on a huge discount to much of the rest of the world, with an average price-earnings ratio (p/e) of just 5.2. At present, the Russian market has a total value of $735 billion. If it traded on the same p/e as the average emerging market (12.5), it would be worth around $1.77 trillion.