полная версия

полная версияAn Outline of Russian Literature

But neither Maikov, Fet, nor Polonsky, exquisite as much of their writing is, produced anything of the calibre of Nekrasov, even in their own province; that is to say, they were none of them as great in the artistic field as he was in his didactic field. Compared with him, they are minor poets. There is one poet of this epoch who does rival Nekrasov in another field, and that is Count Alexis Tolstoy (1817-75), who was also a Parnassian and remained aloof from didactic literature; yet, under the pseudonym of Kuzma Prutkov, he wrote a satire, a collection of platitudes, that are household words in Russia; also a short history of Russia in consummately neat and witty satirical verse. As well as his satires, he wrote an historical novel, Prince Serebryany, and more important still, a trilogy of plays, dealing with the most dramatic epoch of Russian history, that of Ivan the Terrible. The trilogy, written in verse, consists of the “Death of Ivan the Terrible,” “The Tsar Feodor Ivanovitch” and “Tsar Boris.” They are all of them acting plays, form part of the current classical repertory, and are effective, impressive and arresting when played on the stage.

But it is as a poet and as a lyrical poet that Alexis Tolstoy is most widely known. Versatile with a versatility that recalls Pushkin, he writes epical ballads on Russian, Northern, and even Scottish themes, and dramatic poems on Don Juan, St. John Damascene, and Mary Magdalene; and, besides these, a whole series of personal lyrics, which are full of charm, tenderness, music and colour, harmonious in form and transparent. No Russian poet since Pushkin has written such tender love lyrics, and nobody has sung the Russian spring, the Russian summer, and the Russian autumn with such tender lyricism. His poem on the early spring, when the fern is still tightly curled, the shepherd’s note still but half heard in the morning, and the birch trees just green, is one of the most tender, fresh, and perfect expressions of first love, morning, spring, dew, and dawn in the world’s literature. His songs have inspired Tchaikovsky and other composers. The strongest and highest chord he struck is in his St. John Damascene; this contains a magnificent dirge for the dead which can bear comparison even with the Dies Iræ for majesty, solemn pathos, and plangent rhythm.

His pictures of landscapes have a peculiar charm. The following is an attempt at a translation —

“Through the slush and the ruts of the highway,By the side of the dam of the stream,Where the fisherman’s nets are drying,The carriage jogs on, and I dream.I dream, and I look at the highway,At the sky that is sullen and grey,At the lake with its shelving reaches,And the curling smoke far away.By the dam, with a cheerless visageWalks a Jew, who is ragged and sere.With a thunder of foam and of splashing,The waters race over the weir.A boy over there is whistlingOn a hemlock flute of his make;And the wild ducks get up in a panicAnd call as they sweep from the lake.And near the old mill some workmenAre sitting upon the green ground,With a wagon of sacks, a cart horsePlods past with a lazy sound.It all seems to me so familiar,Although I have never been here,The roof of that house out yonder,And the boy, and the wood, and the weir.And the voice of the grumbling mill-wheel,And that rickety barn, I know,I have been here and seen this already,And forgotten it all long ago.The very same horse here was draggingThose sacks with the very same sound,And those very same workmen were sittingBy the rickety mill on the ground.And that Jew, with his beard, walked past me,And those waters raced through the weir;Yes, all this has happened already,But I cannot tell when or where.”The people also produced a poet during this epoch and gave Koltsov a successor, in the person of Nikitin; his themes are taken straight from life, and he became known through his patriotic songs written during the Crimean War; but he is most successful in his descriptions of nature, of sunset on the fields, and dawn, and the swallow’s nest in the grumbling mill. Two other poets, whose work became well known later, but passed absolutely unnoticed in the sixties, were Sluchevsky, a philosophical poet, whose verse, excellent in description, suffers from clumsiness in form, and Apukhtin, whose collected poems and ballads, although he began to write in 1859, were not published until 1886. Apukhtin is a Parnassian. The bulk of his work, though perfect in form, is uninteresting; but he wrote one or two lyrics which have a place in any Russian Golden Treasury, and his poems are largely read now.

In the eighties, a reaction against the anti-poetical tendency set in, and poets began to spring up like mushrooms. Of these, the most popular and the most remarkable is Nadson (1862-87); he died when he was twenty-four, of consumption. Since then his verse has gone through twenty-one editions, and 110,000 copies have been sold; ten editions were published in his own lifetime. And there are innumerable musical settings by various composers to his lyrics. His verse inaugurates a new epoch in Russian poetry, the distinguishing features of which are a great attention to form and technique, a Parnassian love of colour and shape, and a deep melancholy.

Nadson sings the melancholy of youth, the dreams and disillusions of adolescence, and the hopelessness of the stagnant atmosphere of reaction to which he belonged. This last fact accounted in some measure for his extraordinary popularity. But it was by no means its sole cause; his verse is not only exquisite but magically musical, to an extent which makes the verse of other poets seem a stuff of coarser clay, and his pictures of nature, of spring, of night, and especially of night in the Riviera (with a note of passionate home-sickness), have the aromatic, intoxicating sweetness of syringa. Verse such as this, sensitive, ultra-delicate, morbid, nervous, and pessimistic, is bound to have the defects of its qualities, in a marked degree; one is soon inclined to have enough of its sultry, oppressive atmosphere, its delicate perfume, its unrelieved gloom and its music, which is nearly always not only in a minor key but in the same key. Nobody was more keenly aware of this than Nadson himself, and one of his most beautiful poems begins thus —

“Dear friend, I know, I know, I only know too wellThat my verse is barren of all strength, and pale, and delicate,And often just because of its debility I sufferAnd often weep in secret in the silence of the night.”And in another poem he writes his apology. He has never used verse as a toy to chase tedium; the blessed gift of the singer has often been to him an unbearable cross, and he has often vowed to keep silent; but, if the wind blows, the Æolian harp must needs respond, and streams of the hills cannot help rushing to the valley if the sun melts the snow on the mountain tops. This apologia more than all criticism defines his gift. His temperament is an Æolian harp, which, whether it will or no, is sensitive to the breeze; its strings are few, and tuned to one key; nevertheless some of the strains it has sobbed have the stamp of permanence as well as that of ethereal magic.

The poets that come after Nadson belong to the present day; there are many, and they increase in number every year. The so-called “decadent” school were influenced by Shelley, Verlaine, and the French symbolists; but there is nothing which is decadent in the ordinary sense of the word in their verse. Their influence may not be lasting, but they are factors in Russian literature, and some of them, Sologub, Brusov, Balmont, and Ivanov, have produced work which any school would be glad to claim. This is also true of Alexander Bloch, one of the most original as well as one of the most exquisite of living Russian poets.

CONCLUSION

With the death of Turgenev and Dostoyevsky, the great epoch of Russian literature came to an end. A period of literary as well as of political stagnation began, which lasted until the Russo-Japanese War. This was followed by the revolutionary movement, which, in its turn, produced a literary as well as a political chaos, the effect of which and of the manifold reactions it brought about are still being felt. It was only natural, if one considers the extent and the quality of the productions of the preceding epoch, that the soil of literary Russia should require a rest.

As it is, one can count the writers of prominence which the epoch of stagnation produced on one’s fingers – Chekhov, Garshin, Korolenko, and at the end of the period Maxime Gorky, and apart from them, in a by-path of his own, Merezhkovsky. Of these Chekhov and Gorky tower above the others. Chekhov enlarged the range of Russian literature by painting the middle-class and the Intelligentsia, and brought back to Russian literature the note of humour; and Gorky broke altogether fresh ground by painting the vagabond, the artisan, the tramp, the thief, the flotsam and jetsam of the big town and the highway, and by painting in a new manner.

Gorky’s work came like that of Mr. Rudyard Kipling to England, as a revelation. Not only did his subject matter open the doors on dominions undreamed of, but his attitude towards life and that of his heroes towards life seemed to be different from that of all Russian novelists before his advent; and yet the difference between him and his forerunners is not so great as it appears at first sight. It is true that his rough and rebellious heroes, instead of playing the Hamlet, or of finding the solution of life in charity and humility or submission, are partisans of the survival of the fittest with a vengeance, the survival of the strongest fist and the sharpest knife; yet are these new heroes really so different from the uncompromising type that we have already seen sharing one half of the Russian stage, right through the story of Russian literature, from Bazarov back to Peter the Great, and on whose existence was founded the remark that Peter the Great was one of the ingredients in the Russian character? Put Bazarov on the road, or Lermontov, or even Peter the Great, and you get Gorky’s barefooted hero.

Where Gorky created something absolutely new was in the surroundings and in the manner of life which he described, and in the way he described them; this is especially true of his treatment of nature: for the first time in Russian prose literature, we get away from the “orthodox” landscape of convention, and we are face to face with the elements. We feel as if a new breath of air had entered into literature; we feel as people accustomed to the manner in which the poets treated nature in England in the eighteenth century must have felt when Wordsworth, Byron, Shelley and Coleridge began to write.

Chekhov worked on older lines. He descends directly from Turgenev, although his field is a different one. He, more than any other writer and better than any other writer, painted the epoch of stagnation, when Russia, as a Russian once said, was playing itself to death at vindt (an older form of Bridge). The tone of his work is grey, and indeed resembles, as Tolstoy said, that of a photographer, by its objective realism as well as by its absence of high tones; yet if Chekhov is a photographer, he is at the same time a supreme artist, an artist in black and white, and his pessimism is counteracted by two other factors, his sense of humour and his humanity; were it not so, the impression of sadness one would derive from the sum of misery which his crowded stage of merchants, students, squires, innkeepers, waiters, schoolmasters, magistrates, popes, officials, make up between them, would be intolerable. Some of Chekhov’s most interesting work was written for the stage, on which he also brought Scenes of Country Life, which is the sub-title of the play Uncle Vanya. There are the same grey tints, the same weary, amiable, and slack people, bankrupt of ideals and poor in hope, whom we meet in the stories; and here, too, behind the sordid triviality and futility, we hear the “still sad music of humanity.” But in order that the tints of Chekhov’s delicate living and breathing photographs can be effective on the stage, very special acting is necessary, in order to convey the quality of atmosphere which is his special gift. Fortunately he met with exactly the right technique and the appropriate treatment at the Art Theatre at Moscow.

Chekhov died in 1904, soon after the Russo-Japanese War had begun. Apart from the main stream and tradition of Russian fiction and Russian prose, Merezhkovsky occupies a unique place, a place which lies between criticism and imaginative historical fiction, not unlike, in some respects – but very different in others – that which is occupied by Walter Pater in English fiction. His best known work, at least his best known work in Europe, is a prose trilogy, “The Death of the Gods” (a study of Julian the apostate), “The Resurrection of the Gods” (the story of Leonardo da Vinci), and “The Antichrist” (the story of Peter the Great and his son Alexis), which has been translated into nearly every European language. This trilogy is an essay in imaginative historical reconstitution; it testifies to a real and deep culture, and it is lit at times by flashes of imaginative inspiration which make the scenes of the past live; it is alive with suggestive thought; but it is not throughout convincing, there is a touch of Bulwer Lytton as well as a touch of Goethe and Pater in it. Merezhkovsky is perhaps more successful in his purely critical work, his books on Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky and Gogol, which are infinitely stimulating, suggestive, and original, than in his historical fiction, although, needless to say, his criticism appeals to a far narrower public. He is in any case one of the most brilliant and interesting of Russian modern writers, and perhaps the best known outside Russia.

During the war, a writer of fiction made his name by a remarkable book, namely Kuprin, who in his novel, The Duel, gave a vivid and masterly picture of the life of an officer in the line. Kuprin has since kept the promise of his early work. At the same time, Leonid Andreev came forward with short stories, plays, a description of war (The Red Laugh), moralities, not uninfluenced by Maeterlinck, and a limpid and beautiful style in which pessimism seemed to be speaking its last word.

In 1905 the revolutionary movement broke out, with its great hopes, its disillusions, its period of anarchy on the one hand and repression on the other; out of the chaos of events came a chaos of writing rather than literature, and in its turn this produced, in literature as well as in life, a reaction, or rather a series of reactions, towards symbolism, æstheticism, mysticism on the one hand, and towards materialism – not of theory but of practice – on the other. But since these various reactions are now going on, and are vitally affecting the present day, the revolutionary movement of 1905 seems the right point to take leave of Russian literature. In 1905 a new era began, and what that era will ultimately produce, it is too soon even to hazard a guess.

Looking back over the record of Russian literature, the first thing which must strike us, if we think of the literature of other countries, is its comparatively short life. There is in Russian literature no Middle Ages, no Villon, no Dante, no Chaucer, no Renaissance, no Grand Siècle. Literature begins in the nineteenth century. The second thing which will perhaps strike us is that, in spite of its being the youngest of all the literatures, it seems to be spiritually the oldest. In some respects it seems to have become over-ripe before it reached maturity. But herein, perhaps, lies the secret of its greatness, and this may be the value of its contribution to the soul of mankind. It is —

“Old in grief and very wise in tears”:

and its chief gift to mankind is an expression, made with a naturalness and sincerity that are matchless, and a love of reality which is unique, – for all Russian literature, whether in prose or verse, is rooted in reality – of that grief and that wisdom; the grief and wisdom which come from a great heart; a heart that is large enough to embrace the world and to drown all the sorrows therein with the immensity of its sympathy, its fraternity, its pity, its charity, and its love.

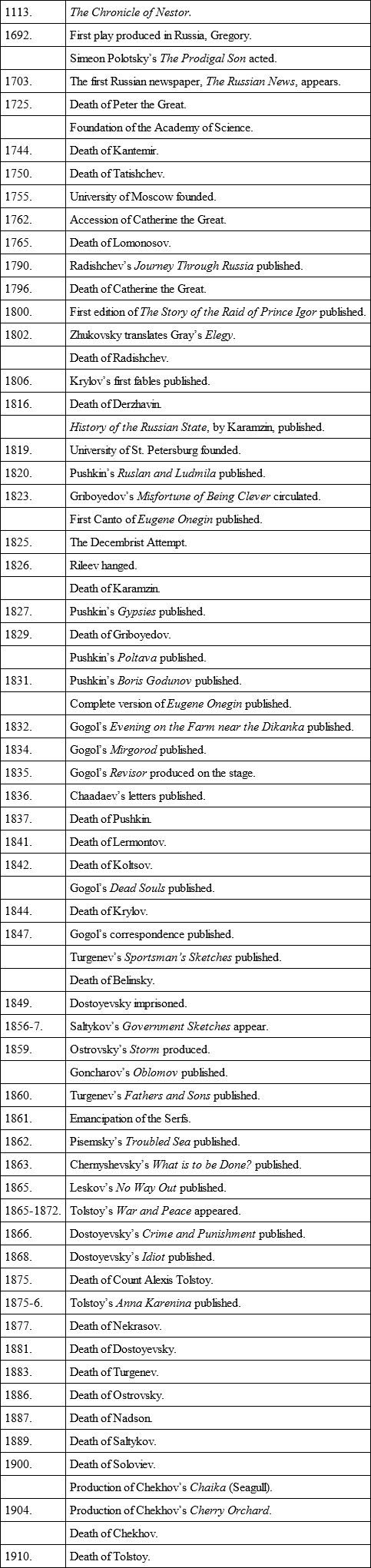

CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE

1

Another copy of it was found in 1864 amongst the papers of Catherine I. Pushkin left a remarkable analysis of the epic.

2

Not 1763, as generally stated in his biographies.

3

The poem was originally called Mazepa: Pushkin changed the title so as not to clash with Byron. It is interesting to see what Pushkin says of Byron’s poem. In his notes there is the following passage —

“Byron knew Mazepa through Voltaire’s history of Charles XII. He was struck solely by the picture of a man bound to a wild horse and borne over the steppes. A poetical picture of course; but see what he did with it. What a living creation! What a broad brush! But do not expect to find either Mazepa or Charles, nor the usual gloomy Byronic hero. Byron was not thinking of him. He presented a series of pictures, one more striking than the other. Had his pen come across the story of the seduced daughter and the father’s execution, it is improbable that anyone else would have dared to touch the subject.”