полная версия

полная версияDumas' Paris

The last sentence seems rather superfluous, – if it was justifiable, – but, after all, no harm probably was done, and Dumas as a rule was never vituperative.

Continuing, these first pages give us an account of the difficulties under which poor Louis Ange Pitou acquired his knowledge of Latin, which is remarkably like the account which Dumas gives in the “Mémoires” of his early acquaintance with the classics.

When Pitou leaves Haramont, his native village, and takes to the road, and visits Billot at “Bruyere aux Loups,” knowing well the road, as he did that to Damploux, Compiègne, and Vivières, he was but covering ground equally well known to Dumas’ own youth.

Finally, as he is joined by Billot en route for Paris, and takes the highroad from Villers-Cotterets, near Gondeville, passing Nanteuil, Dammartin, and Ermenonville, arriving at Paris at La Villette, he follows almost the exact itinerary taken by the venturesome Dumas on his runaway journey from the notary’s office at Crépy-en-Valois.

Crépy-en-Valois was the near neighbour of Villers-Cotterets, which jealously attempted to rival it, and does even to-day. In “The Taking of the Bastille” Dumas only mentions it in connection with Mother Sabot’s âne, “which was shod,” – the only ass which Pitou had ever known which wore shoes, – and performed the duty of carrying the mails between Crépy and Villers-Cotterets.

At Villers-Cotterets one may come into close contact with the château which is referred to in the later pages of the “Vicomte de Bragelonne.” “Situated in the middle of the forest, where we shall lead a most sentimental life, the very same where my grandfather,” said Monseigneur the Prince, “Henri IV. did with ‘La Belle Gabrielle.’”

So far as lion-hunting goes, Dumas himself at an early age appears to have fallen into it. He recalls in “Mes Mémoires” the incident of Napoleon I. passing through Villers-Cotterets just previous to the battle of Waterloo.

“Nearly every one made a rush for the emperor’s carriage,” said he; “naturally I was one of the first… Napoleon’s pale, sickly face seemed a block of ivory… He raised his head and asked, ‘Where are we?’ ‘At Villers-Cotterets, Sire,’ said a voice. ‘Go on.’” Again, a few days later, as we learn from the “Mémoires,” “a horseman coated with mud rushes into the village; orders four horses for a carriage which is to follow, and departs… A dull rumble draws near … a carriage stops… ‘Is it he – the emperor?’ Yes, it was the emperor, in the same position as I had seen him before, exactly the same, pale, sickly, impassive; only the head droops rather more… ‘Where are we?’ he asked. ‘At Villers-Cotterets, Sire.’ ‘Go on.’”

That evening Napoleon slept at the Elysée. It was but three months since he had returned from Elba, but in that time he came to an abyss which had engulfed his fortune. That abyss was Waterloo; only saved to the allies – who at four in the afternoon were practically defeated – by the coming up of the Germans at six.

Among the books of reference and contemporary works of a varying nature from which a writer in this generation must build up his facts anew, is found a wide difference in years as to the date of the birth of Dumas père.

As might be expected, the weight of favour lies with the French authorities, though by no means do they, even, agree among themselves.

His friends have said that no unbiassed, or even complete biography of the author exists, even in French; and possibly this is so. There is about most of them a certain indefiniteness and what Dumas himself called the “colour of sour grapes.”

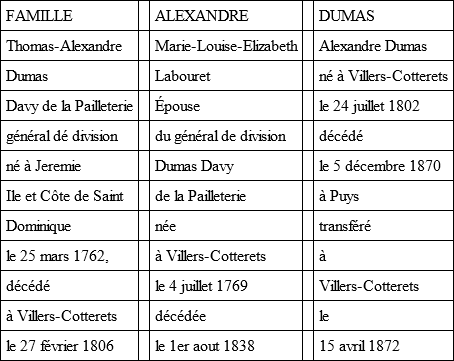

The exact date of his birth, however, is unquestionably 1802, if a photographic reproduction of his natal certificate, published in Charles Glinel’s “Alex. Dumas et Son Œuvre,” is what it seems to be.

Dumas’ aristocratic parentage – for such it truly was – has been the occasion of much scoffing and hard words. He pretended not to it himself, but it was founded on family history, as the records plainly tell, and whether Alexandre, the son of the brave General Dumas, the Marquis de la Pailleterie, was prone to acknowledge it or not does not matter in the least. The “feudal particle” existed plainly in his pedigree, and with no discredit to any concerned.

General Dumas, his wife, and his son are buried in the cemetery of Villers-Cotterets, where the exciting days of the childhood of Dumas, the romancer, were spent, in a plot of ground “conceded in perpetuity to the family.” The plot forms a rectangle six metres by five, surrounded by towering pines.

The three monuments contained therein are of the utmost simplicity, each consisting of an inclined slab of stone.

The inscriptions are as follows:

There would seem to be no good reason why a book treating of Dumas’ Paris might not be composed entirely of quotations from Dumas’ own works. For a fact, such a work would be no less valuable as a record than were it evolved by any other process. It would indeed be the best record that could possibly be made, for Dumas’ topography was generally truthful if not always precise.

There are, however, various contemporary side-lights which are thrown upon any canvas, no matter how small its area, and in this instance they seem to engulf even the personality of Dumas himself, to say nothing of his observations.

Dumas was such a part and parcel of the literary life of the times in which he lived that mention can scarce be made of any contemporary event that has not some bearing on his life or work, or he with it, from the time when he first came to the metropolis (in 1822) at the impressionable age of twenty, until the end.

It will be difficult, even, to condense the relative incidents which entered into his life within the confines of a single volume, to say nothing of a single chapter. The most that can be done is to present an abridgment which shall follow along the lines of some preconceived chronological arrangement. This is best compiled from Dumas’ own words, leaving it to the additional references of other chapters to throw a sort of reflected glory from a more distant view-point.

The reputation of Dumas with the merely casual reader rests upon his best-known romances, “Monte Cristo,” 1841; “Les Trois Mousquetaires,” 1844; “Vingt Ans Après,” 1845; “Le Vicomte de Bragelonne,” 1847; “La Dame de Monsoreau,” 1847; and his dramas of “Henri III. et Sa Cour,” 1829, “Antony,” 1831, and “Kean,” 1836.

His memoirs, “Mes Mémoires,” are practically closed books to the mass of English readers – the word books is used advisedly, for this remarkable work is composed of twenty stout volumes, and they only cover ten years of the author’s life.

Therein is a mass of fact and fancy which may well be considered as fascinating as are the “romances” themselves, and, though autobiographic, one gets a far more satisfying judgment of the man than from the various warped and distorted accounts which have since been published, either in French or English.

Beginning with “Memories of My Childhood” (1802-06), Dumas launches into a few lines anent his first visit to Paris, in company with his father, though the auspicious – perhaps significant – event took place at a very tender age. It seems remarkable that he should have recalled it at all, but he was a remarkable man, and it seems not possible to ignore his words.

“We set out for Paris, ah, that journey! I recollect it perfectly… It was August or September, 1805. We got down in the Rue Thiroux at the house of one Dollé… I had been embraced by one of the most noble ladies who ever lived, Madame la Marquise de Montesson, widow of Louis-Philippe d’Orleans… The next day, putting Brune’s sword between my legs and Murat’s hat upon my head, I galloped around the table; when my father said, ‘Never forget this, my boy.’… My father consulted Corvisart, and attempted to see the emperor, but Napoleon, the quondam general, had now become the emperor, and he refused to see my father… To where did we return? I believe Villers-Cotterets.”

Again on the 26th of March, 1813, Dumas entered Paris in company with his mother, now widowed. He says of this visit:

“I was delighted at the prospect of this my second visit… I have but one recollection, full of light and poetry, when, with a flourish of trumpets, a waving of banners, and shouts of ‘Long live the King of Rome,’ was lifted up above the heads of fifty thousand of the National Guard the rosy face and the fair, curly head of a child of three years – the infant son of the great Napoleon… Behind him was his mother, – that woman so fatal to France, as have been all the daughters of the Cæsars, Anne of Austria, Marie Antoinette, and Marie Louise, – an indistinct, insipid face… The next day we started home again.”

Through the influence of General Foy, an old friend of his father’s, Dumas succeeded in obtaining employment in the Orleans Bureau at the Palais Royal.

His occupation there appears not to have been unduly arduous. The offices were in the right-hand corner of the second courtyard of the Palais Royal. He remained here in this bureau for a matter of five years, and, as he said, “loved the hour when he came to the office,” because his immediate superior, Lassagne, – a contributor to the Drapeau Blanc, – was the friend and intimate of Désaugiers, Théaulon, Armand Gouffé, Brozier, Rougemont, and all the vaudevillists of the time.

Dumas’ meeting with the Duc d’Orleans – afterward Louis-Philippe – is described in his own words thus: “In two words I was introduced. ‘My lord, this is M. Dumas, whom I mentioned to you, General Foy’s protégé.’ ‘You are the son of a brave man,’ said the duc, ‘whom Bonaparte, it seems, left to die of starvation.’… The duc gave Oudard a nod, which I took to mean, ‘He will do, he’s by no means bad for a provincial.’” And so it was that Dumas came immediately under the eye of the duc, engaged as he was at that time on some special clerical work in connection with the duc’s provincial estates.

The affability of Dumas, so far as he himself was concerned, was a foregone conclusion. In the great world in which he moved he knew all sorts and conditions of men. He had his enemies, it is true, and many of them, but he himself was the enemy of no man. To English-speaking folk he was exceedingly agreeable, because, – quoting his own words, – said he, “It was a part of the debt which I owed to Shakespeare and Scott.” Something of the egoist here, no doubt, but gracefully done nevertheless.

With his temperament it was perhaps but natural that Dumas should have become a romancer. This was of itself, maybe, a foreordained sequence of events, but no man thinks to-day that, leaving contributary conditions, events, and opportunities out of the question, he shapes his own fate; there are accumulated heritages of even distant ages to contend with. In Dumas’ case there was his heritage of race and colour, refined, perhaps, by a long drawn out process, but, as he himself tells in “Mes Mémoires,” his mother’s fear was that her child would be born black, and he was, or, at least, purple, as he himself afterward put it.

CHAPTER III.

DUMAS’ LITERARY CAREER

Just how far Dumas’ literary ability was an inheritance, or growth of his early environment, will ever be an open question. It is a manifest fact that he had breathed something of the spirit of romance before he came to Paris.

Although it was not acknowledged until 1856, “The Wolf-Leader” was a development of a legend told to him in his childhood. Recalling then the incident of his boyhood days, and calling into recognition his gift of improvisation, he wove a tale which reflected not a little of the open-air life of the great forest of Villers-Cotterets, near the place of his birth.

Here, then, though it was fifty years after his birth, and thirty after he had thrust himself on the great world of Paris, the scenes of his childhood were reproduced in a wonderfully romantic and weird tale – which, to the best of the writer’s belief, has not yet appeared in English.

To some extent it is possible that there is not a little of autobiography therein, not so much, perhaps, as Dickens put into “David Copperfield,” but the suggestion is thrown out for what it may be worth.

It is, furthermore, possible that the historic associations of the town of Villers-Cotterets – which was but a little village set in the midst of the surrounding forest – may have been the prime cause which influenced and inspired the mind of Dumas toward the romance of history.

In point of chronology, among the earliest of the romances were those that dealt with the fortunes of the house of Valois (fourteenth century), and here, in the little forest town of Villers-Cotterets, was the magnificent manor-house which belonged to the Ducs de Valois; so it may be presumed that the sentiment of early associations had somewhat to do with these literary efforts.

All his life Dumas devotedly admired the sentiment and fancies which foregathered in this forest, whose very trees and stones he knew so well. From his “Mémoires” we learn of his indignation at the destruction of its trees and much of its natural beauty. He says:

“This park, planted by François I., was cut down by Louis-Philippe. Trees, under whose shade once reclined François I. and Madame d’Etampes, Henri II. and Diane de Poitiers, Henri IV. and Gabrielle d’Estrées – you would have believed that a Bourbon would have respected you. But over and above your inestimable value of poetry and memories, you had, unhappily, a material value. You beautiful beeches with your polished silvery cases! you beautiful oaks with your sombre wrinkled bark! – you were worth a hundred thousand crowns. The King of France, who, with his six millions of private revenue, was too poor to keep you – the King of France sold you. For my part, had you been my sole possession, I would have preserved you; for, poet as I am, one thing that I would set before all the gold of the earth: the murmur of the wind in your leaves; the shadow that you made to flicker beneath my feet; the visions, the phantoms, which, at eventide, betwixt the day and night, in the doubtful hour of twilight, would glide between your age-long trunks as glide the shadows of the ancient Abencerrages amid the thousand columns of Cordova’s royal mosque.”

What wonder, with these lines before one, that the impressionable Dumas was so taken with the romance of life and so impracticable in other ways.

From the fact that no thorough biography of Dumas exists, it will be difficult to trace the fluctuations of his literary career with preciseness. It is not possible even with the twenty closely packed volumes of the “Mémoires” – themselves incomplete – before one. All that a biographer can get from this treasure-house are facts, – rather radiantly coloured in some respects, but facts nevertheless, – which are put together in a not very coherent or compact form.

They do, to be sure, recount many of the incidents and circumstances attendant upon the writing and publication of many of his works, and because of this they immediately become the best of all sources of supply. It is to be regretted that these “Mémoires” have not been translated, though it is doubtful if any publisher of English works could get his money back from the transaction.

Other clues as to his emotions, and with no uncertain references to incidents of Dumas’ literary career, are found in “Mes Bêtes,” “Ange Pitou,” the “Causeries,” and the “Travels.” These comprise many volumes not yet translated.

Dumas was readily enough received into the folds of the great. Indeed, as we know, he made his entrée under more than ordinary, if not exceptional, circumstances, and his connection with the great names of literature and statecraft extended from Hugo to Garibaldi.

As for his own predilections in literature, Dumas’ own voice is practically silent, though we know that he was a romanticist pure and simple, and drew no inspiration or encouragement from Voltairian sentiments. If not essentially religious, he at least believed in its principles, though, as a warm admirer has said, “He had no liking for the celibate and bookish life of the churchman.”

Dumas does not enter deeply into the subject of ecclesiasticism in France. His most elaborate references are to the Abbey of Ste. Genevieve – since disappeared in favour of the hideous pagan Panthéon – and its relics and associations, in “La Dame de Monsoreau.” Other of the romances from time to time deal with the subject of religion more or less, as was bound to be, considering the times of which he wrote, of Mazarin, Richelieu, De Rohan, and many other churchmen.

Throughout the thirties Dumas was mostly occupied with his plays, the predominant, if not the most sonorous note, being sounded by “Antony.”

As a novelist his star shone brightest in the decade following, commencing with “Monte Cristo,” in 1841, and continuing through “Le Vicomte de Bragelonne” and “La Dame de Monsoreau,” in 1847.

During these strenuous years Dumas produced the flower of his romantic garland – omitting, of course, certain trivial and perhaps unworthy trifles, among which are usually considered, rightly enough, “Le Capitaine Paul” (Paul Jones) and “Jeanne d’Arc.” At this period, however, he produced the charming and exotic “Black Tulip,” which has since come to be a reality. The best of all, though, are admittedly the Mousquetaire cycle, the volumes dealing with the fortunes of the Valois line, and, again, “Monte Cristo.”

By 1830, Dumas, eager, as it were, to experience something of the valiant boisterous spirit of the characters of his romances, had thrown himself heartily into an alliance with the opponents of Louis-Philippe. Orleanist successes, however, left him to fall back upon his pen.

In 1844, having finished “Monte Cristo,” he followed it by “Les Trois Mousquetaires,” and before the end of the same year had put out forty volumes, by what means, those who will read the scurrilous “Fabrique des Romans” – and properly discount it – may learn.

The publication of “Monte Cristo” and “Les Trois Mousquetaires” as newspaper feuilletons, in 1844-45, met with amazing success, and were, indeed, written from day to day, to keep pace with the demands of the press.

Here is, perhaps, an opportune moment to digress into the ethics of the profession of the “literary ghost,” and but for the fact that the subject has been pretty well thrashed out before, – not only with respect to Dumas, but to others as well, – it might justifiably be included here at some length, but shall not be, however.

The busy years from 1840-50 could indeed be “explained” – if one were sure of his facts; but beyond the circumstances, frequently availed of, it is admitted, of Dumas having made use of secretarial assistance in the productions which were ultimately to be fathered by himself, there is little but jealous and spiteful hearsay to lead one to suppose that he made any secret of the fact that he had some very considerable assistance in the production of the seven hundred volumes which, at a late period in his life, he claimed to have produced.

The “Maquet affaire,” of course, proclaims the whilom Augustus Mackeat as a collaborateur; still the ingenuity of Dumas shines forth through the warp and woof in an unmistakable manner, and he who would know more of the pros and cons is referred to the “Maison Dumas et Cie.”

Maquet was manifestly what we have come to know as a “hack,” though the species is not so very new – nor so very rare. The great libraries are full of them the whole world over, and very useful, though irresponsible and ungrateful persons, many of them have proved to be. Maquet, at any rate, served some sort of a useful purpose, and he certainly was a confidant of the great romancer during these very years, but that his was the mind and hand that evolved or worked out the general plan and detail of the romances is well-nigh impossible to believe, when one has digested both sides of the question.

An English critic of no inconsiderable knowledge has thrown in his lot recently with the claims of Maquet, and given the sole and entire production of “Les Trois Mousquetaires,” “Monte Cristo,” “La Dame de Monsoreau,” and many other of Dumas’ works of this period, to him, placing him, indeed, with Shakespeare, whose plays certain gullible persons believe to have been written by Bacon. The flaw in the theory is apparent when one realizes that the said Maquet was no myth – he was, in fact, a very real person, and a literary personage of a certain ability. It is strange, then, that if he were the producer of, say “Les Trois Mousquetaires,” which was issued ostensibly as the work of Dumas, that he wrote nothing under his own name that was at all comparable therewith; and stranger still, that he was able to repeat this alleged success with “Monte Cristo,” or the rest of the Mousquetaire series, and yet not be able to do the same sort of a feat when playing the game by himself. One instance would not prove this contention, but several are likely to not only give it additional strength, but to practically demonstrate the correct conclusion.

The ethics of plagiarism are still greater and more involved than those which make justification for the employment of one who makes a profession of library research, but it is too involved and too vast to enter into here, with respect to accusations of its nature which were also made against Dumas.

As that new star which has so recently risen out of the East – Mr. Kipling – has said, “They took things where they found them.” This is perhaps truthful with regard to most literary folk, who are continually seeking a new line of thought. Scott did it, rather generously one might think; even Stevenson admitted that he was greatly indebted to Washington Irving and Poe for certain of the details of “Treasure Island” – though there is absolutely no question but that it was a sort of unconscious absorption, to put it rather unscientifically. The scientist himself calls it the workings of the subconscious self.

As before said, the Maquet affaire was a most complicated one, and it shall have no lengthy consideration here. Suffice to say that, when a case was made by Maquet in court, in 1856-58, Maquet lost. “It is not justice that has won,” said Maquet, “but Dumas.”

Edmond About has said that Maquet lived to speak kindly of Dumas, “as did his legion of other collaborateurs; and the proudest of them congratulate themselves on having been trained in so good a school.” This being so, it is hard to see anything very outrageous or preposterous in the procedure.

Blaze de Bury has described Dumas’ method thus:

“The plot was worked over by Dumas and his colleague, when it was finally drafted by the other and afterward rewritten by Dumas.”

M. About, too, corroborates Blaze de Bury’s statement, so it thus appears legitimately explained. Dumas at least supplied the ideas and the esprit.

In Dumas’ later years there is perhaps more justification for the thought that as his indolence increased – though he was never actually inert, at least not until sickness drew him down – the authorship of the novels became more complex. Blaze de Bury put them down to the “Dumas-Legion,” and perhaps with some truth. They certainly have not the vim and fire and temperament of individuality of those put forth from 1840 to 1850.

Dumas wrote fire and impetuosity into the veins of his heroes, perhaps some of his very own vivacious spirit. It has been said that his moral code was that of the camp or the theatre; but that is an ambiguity, and it were better not dissected.

Certainly he was no prude or Puritan, not more so, at any rate, than were Burns, Byron, or Poe, but the virtues of courage, devotion, faithfulness, loyalty, and friendship were his, to a degree hardly excelled by any of whom the written record of cameraderie exists.

Dumas has been jibed and jeered at by the supercilious critics ever since his first successes appeared, but it has not leavened his reputation as the first romancer of his time one single jot; and within the past few years we have had a revival of the character of true romance – perhaps the first true revival since Dumas’ time – in M. Rostand’s “Cyrano de Bergerac.”