Полная версия

How to write essays (English for Academic Purposes)

So, brainstorming should be seen as distinct from analysis. It needs to be done straight after you’ve completed your analysis, which in turn needs to be done as soon as you have decided upon the question you’re going to tackle. This will give your subconscious time to go away and riffle through your data banks for what it needs before you begin to set about your research.

If you don’t make clear your own ideas and your interpretation of the implications of the question, your thinking is likely to be hijacked by the author and his or her intentions. If you don’t ask your author clear questions you are not likely to get the clear, relevant answers you want.

Now that you’ve analysed the implications, use this to empty your mind on the question. Most of us are all too eager to convince ourselves that we know nothing about a subject and, therefore, we have no choice but to skip this stage and go straight into the books. But no matter what the subject, I have never found a group of students, despite all their declarations of ignorance and all their howls of protest, who were not able to put together a useful structure of ideas that would help them to decide as they read what’s relevant to the essay and what’s not. Once we tap into our own knowledge and experience, we can all come up with ideas and a standard by which to judge the author’s point of view, which will liberate us from being poor helpless victims of what we read. We all have ideas and experience that allow us to negotiate with texts, evaluating the author’s opinions, while we select what we want to use and discard the rest. Throughout this stage, although you’re constantly checking your ideas for relevance, don’t worry if your mind flows to unexpected areas and topics as the ideas come tumbling out. The important point is to get the ideas onto the page and to let the mind’s natural creativity and self-organisation run its course, until you’ve emptied your mind. Later you can edit the ideas, discarding those that are not strictly relevant to the question.

One of the most effective methods for the brainstorming stage is the method known as ‘pattern notes’. Rather than starting at the top of the page and working down in a linear form in sentences or lists, you start from the centre with the title of the essay and branch out with your analysis of concepts or other ideas as they form in your mind.

The advantage of this method is that it allows you to be much more creative, because it leaves the mind as free as possible to analyse concepts, make connections and contrasts, and to pursue trains of thought. As you’re restricted to using just single words or simple phrases, you’re not trapped in the unnecessary task of constructing complete sentences. Most of us are familiar with the frustration of trying to catch the wealth of ideas the mind throws up, while at the same time struggling to write down the sentences they’re entangled in. As a result we see exciting ideas come and go without ever being able to record them quickly enough.

The point is that the mind can work so much faster than we can write, so we need a system that can catch all the ideas it can throw up, and give us the freedom to put them into whatever order or form appears to be right. The conventional linear strategy of taking notes restricts us in both of these ways. Not only does it tie us down to constructing complete sentences, or at least meaningful phrases, which means we lose the ideas as we struggle to find the words, but even more important, we’re forced to deal with the ideas in sequence, in one particular order, so that if any ideas come to us out of that sequence, we must discard them and hope we can pick them up later. Sadly, that hope is more often forlorn: when we try to recall the ideas, we just can’t.

The same is true when we take linear notes from the books we read. Most of us find that once we’ve taken the notes we’re trapped within the order in which the author has dealt with the ideas and we’ve noted them. It’s not impossible, but it’s difficult to escape from this. By contrast, pattern notes give us complete freedom over the final order of our ideas. It’s probably best explained by comparing it to the instructions you might get from somebody if you were to ask them the way to a particular road. They would give you a linear list of instructions (e.g. ‘First, go to the end of the road, then turn right. When you get to the traffic lights, etc.’). This forces you to follow identically the route they would take themselves. If you don’t, you’re lost. By contrast, pattern notes are like a copy of a map or the A to Z of a large city: you can see clearly the various routes you can take, so you can make your own choices.

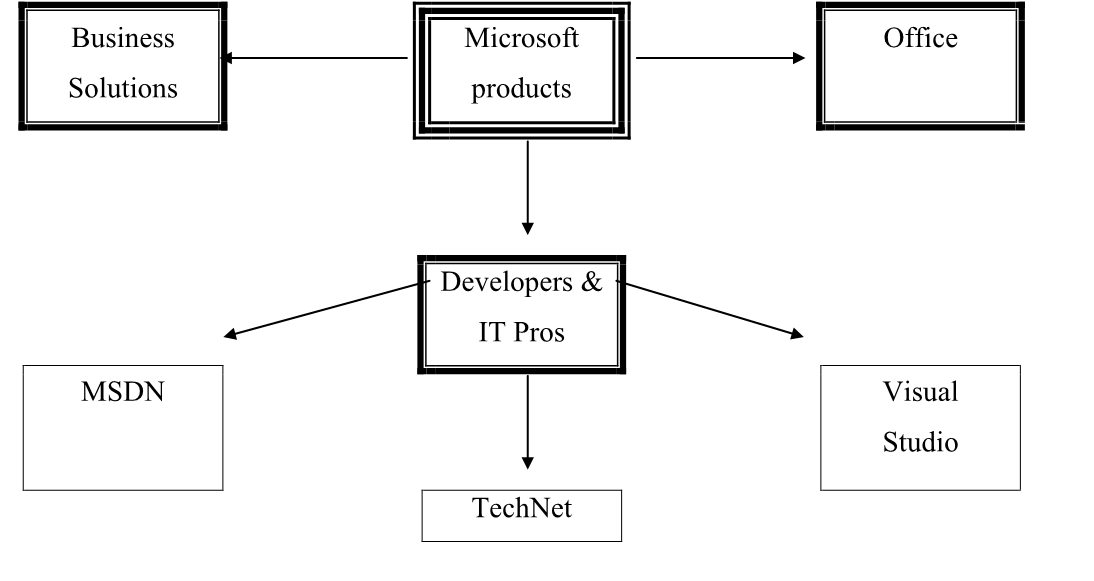

So mapping is one of the affective ways to organize your ideas. To make a map use a whole sheet of paper, and write your topic in the middle, with a circle around it. Then put the next idea in a circle above or below your topic, and connect the circles with lines. The lines show that the two ideas are related.

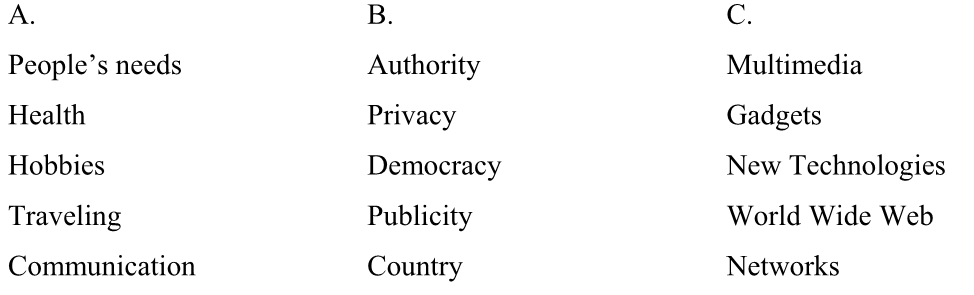

4. Choose one topic from each of three groups. Brainstorm one of the topics (list as many ideas as you can in five minutes), make ‘pattern notes’ to the second topic (use any resources you can) and map the third topic. Share your notes with partners.

Pre-Writing: Using the Right Ability

So far we have seen how important it is to interpret the question carefully, because it tells us the structure our essay should adopt for us to deal relevantly with all the issues it raises. With this clear in our mind we can avoid taking masses of irrelevant notes, which are likely to find their way into our essays, making them irrelevant, shapeless and confusing.

There is one more important thing to take into account: the range of abilities we are expected to use. This is normally made clear through what is known as ‘instructional verbs’. Given below is a list of short definitions of those most frequently found in questions, which should help you avoid the common problems that arise when you overlook or misinterpret them.

Analyse – separate an argument, a theory, or a claim into its elements or component parts; to trace the causes of a particular event; to reveal the general principles underlying phenomena.

Compare – look for similarities and differences between two or more things, problems or arguments. Perhaps, although not always, reach a conclusion about which you think is preferable.

Contrast – set in opposition to each other two or more things, problems or arguments in order to identify clearly their differences and their individual characteristics.

Criticise – identify the weaknesses of certain theories, opinions or claims, and give your judgement about their merit. Support your judgements with a discussion of the evidence and the reasoning involved.

Define – outline the precise meaning of a word or phrase. In some cases it may be necessary or desirable to examine different possible, or often used, definitions.

Describe – give a detailed or graphic account, keeping to the facts or to the impressions that an event had upon you. In history this entails giving a narrative account of the events in the time sequence they occurred.

Discuss – investigate or examine by argument; sift through the arguments and the evidence used to support them, giving reasons for and against both sides; examine the implications. It means playing devil’s advocate by arguing not just for the side of the argument that you support, but for the side with which you may have little sympathy.

Evaluate – make an appraisal of the worth of something, an argument or a set of beliefs, in the light of their truth or usefulness. This does involve making your own value judgements, but not just naked opinion: they must be backed up by argument and justification.

Explain – make plain; interpret and account for the occurrence of a particular event by giving the causes. Unlike the verb ‘to describe’, this does not mean that it is sufficient to describe what happened by giving a narrative of the events. To explain an event is to give the reasons why it occurred, usually involving an analysis of the causes.

Illustrate – explain or clarify something by the use of diagrams, figures or concrete examples.

Interpret – reveal what you believe to be the meaning or significance of something; to make sense of something that might otherwise be unclear, or about which there may be more than one opinion. So usually this involves giving your own judgement.

Justify – show adequate grounds for a decision or a conclusion by supporting it with sufficient evidence and argument; answer the main objections that are likely to be made to it.

Outline – give the main features or the general principles of a subject, omitting minor details and emphasising its structure and arrangement.

Relate – this usually means one of two things. In some questions it means narrate a sequence of events – outline the story of a particular incident. Alternatively, it can mean show how certain things are connected or affect each other, or show to what extent they are alike.

Review – examine closely a subject or a case that has been put forward for a certain proposal or argument. Usually, although not always, this means concluding with your own judgement as to the strength of the case. However, if it involves examining just a subject or a topic, and not an argument or a proposal, it will mean just examining in some detail all the aspects of the topic.

State – outline briefly and clearly the facts of the situation or a side of an argument. This doesn’t call for argument or discussion, just the presentation of the facts or the arguments. Equally it doesn’t call for a judgement from you, just reportage.

Summarise – give a clear and concise account of the principal points of a problem or an argument, omitting the details, evidence and examples that may have been given to support the argument or illustrate the problem.

Trace – outline the stages in the development of a particular issue or the history of a topic.

5. Gather together as many research papers or articles you have ever read or touched upon for your course as you can, at least enough to give you a representative sample.

For each paper, list the questions in three columns: those that ask for a descriptive and factual answer (the ‘what’, ‘how’ and ‘describe’ type of question); those that ask for an analytical answer (the ‘outline’, ‘analyse’, ‘compare’ and ‘contrast’ type of question); and those that ask you for a discussion of the issues (the ‘criticise’, ‘evaluate’ and ‘discuss’ type of question).

Once you’ve done this, calculate the percentage of each type of question on each paper.

STAGE 2

Research

We have now reached the point where we can confidently set about our research. We’ve interpreted the meaning and implications of the question, in the course of which we’ve analysed the key concepts involved. From there we’ve brainstormed the question using our interpretation as our key structure. As a result, we now know two things: what questions we want answered from our research; and what we already know about the topic.

There are three main key skills in research: reading, note-taking and organisation.

It’s important to read purposefully: to be clear about why we’re reading a particular passage so that we can select the most appropriate reading strategy. Many of us get into the habit of reading every passage word-forword, regardless of our purpose in reading it, when in fact it might be more efficient to skim or scan it. Adopting a more flexible approach to our reading in this way frees up more of our time, so that we can read around our subject and take on board more ideas and information.

It also gives us more time to process the ideas. We will see how important this is if we are to avoid becoming just ‘surface-level processors’, reading passively without analysing and structuring what we read, or criticising and evaluating the arguments presented. We will examine the techniques involved in analysing a passage to extract its structure, so that we can recall the arguments, ideas and evidence more effectively. We will also learn the different ways we can improve our ability to criticise and evaluate the arguments we read. In this way we can become ‘deep-level processors’, actively processing what we read and generating more of our own ideas.

But before you hit the books, a warning! It’s all too easy to pick up a pile of books that appear vaguely useful and browse among them. This might be enjoyable, and you might learn something, but it will hardly help you get your essay written. Now that you’ve interpreted the question and you’ve brainstormed the issues, you have a number of questions and topics you want to pursue. You are now in a position to ask clear questions as you read the books and the other materials you’ve decided to use in your research.

Nevertheless, before you begin you need to pin down exactly the sections of each book that are relevant to your research. Very few of the books you use will you read from cover to cover. With this in mind, you need to consult the contents and index pages in order to locate those pages that deal with the questions and issues you’re interested in.

To ensure that you’re able to do ‘deep-level processing’, it may be necessary to accept that you need to do two or three readings of the text, particularly if it is technical and closely argued.

Reading for comprehension

In your first reading you might aim just for the lower ability range, for comprehension, just to understand the author’s arguments. It may be a subject you’ve never read about before, or it may include a number of unfamiliar technical terms that you need to think about carefully each time they are used.

Reading for analysis and structure

In the next reading you should be able to analyse the passage into sections and subsections, so that you can see how you’re going to organise it in your notes. If the text is not too difficult you may be able to accomplish both of these tasks (comprehension and analysis) in one reading, but always err on the cautious side, don’t rush it. Remember, now that you’ve identified just those few pages that you have to read, rather than the whole book, you can spend more time processing the ideas well.

Reading for criticism and evaluation

The third reading involves criticising and evaluating your authors’ arguments. It’s clear that in this and the second reading our processing is a lot more active. While in the second we’re analysing the passage to take out the structure, in this, the third, we’re maintaining a dialogue with the authors, through which we’re able to criticise and evaluate their arguments. To help you in this, keep the following sorts of questions in mind as you read.

• Are the arguments consistent or are they contradictory?

• Are they relevant (i.e. do the authors use arguments they know you’ll agree with, but which are not relevant to the point they’re making)?

• Do they use the same words to mean different things at different stages of the argument (what’s known as the fallacy of equivocation)?

• Are there underlying assumptions that they haven’t justified?

• Can you detect bias in the argument?

• Do they favour one side of the argument, giving little attention to the side for which they seem to have least sympathy? For example, do they give only those reasons that support their case, omitting those that don’t (the fallacy of special pleading)?

• Is the evidence they use relevant?

• Is it strong enough to support their arguments?

• Do they use untypical examples, which they know you will have to agree with, in order to support a difficult or extreme case (what’s known as the fallacy of the straw man)?

• Do they draw conclusions from statistics and examples which can’t adequately support them?

This sounds like a lot to remember, and it is, so don’t try to carry this list along with you as you read. Just remind yourself of it before you begin to criticise and evaluate the text. Having done this two or three times you will find more and more of it sticks and you won’t need reminding. Then, after you’ve finished the passage, go through the list again and check with what you can recall of the text. These are the sort of questions you will be asking in Stage 5 (Revision) about your own essay before you hand it in. So it’s a good idea to develop your skills by practising on somebody else first.

One last caution – don’t rush into this. You will have to give yourself some breathing space between the second reading and this final evaluative reading. Your mind will need sufficient time to process all the material, preferably overnight, in order for you to see the issues clearly and objectively. If you were to attempt to criticise and evaluate the author’s ideas straight after reading them for the structure, your own ideas would be so assimilated into the author’s, that you would be left with no room to criticise and assess them. You would probably find very little to disagree with the author about.

Many of the same issues resurface when we consider note-taking. As with reading, we will see that it’s important not to tie ourselves to one strategy of note-taking irrespective of the job we have to do. We will see that for different forms of processing there are the most appropriate strategies of note-taking: linear notes for analysis and structure, and pattern notes for criticism and evaluation. Cultivating flexibility in our pattern of study helps us choose the most effective strategy and, as a result, get the most out of our intellectual abilities.

But our problems in note-taking don’t end there. The best notes help us structure our own thoughts, so we can recall and use them quickly and accurately, particularly under timed conditions. In this lie many of the most common problems in note-taking, particularly the habit of taking too many notes that obscure the structure, making it difficult to recall. We will exam ways of avoiding this by creating clear uncluttered notes that help us recall even the most complex structures accurately. Given this, and the simple techniques of consolidating notes, we will see how revision for the exam can become a more manageable, less daunting task.

Finally, if our notes are going to help us recall the ideas, arguments and evidence we read, as well as help us to criticise and evaluate an author’s arguments, they must be a reflection of our own thinking. We will examine the reasons why many students find it difficult to have ideas of their own, when they read and take notes from their sources, and how this affects their concentration while they work.

As we’ve already discovered, our aim here is to identify and extract the hierarchy of ideas, a process which involves selecting and rejecting material according to its relevance and importance. Although by now this sounds obvious, it’s surprising how many students neglect it or just do it badly. As with most study skills, few of us are ever shown how best to structure our thoughts on paper. Yet there are simple systems we can all learn. Some students never get beyond the list of isolated points, devoid of all structure. Or, worse still, they rely on the endless sequence of descriptive paragraphs, in which a structure hides buried beneath a plethora of words. This makes it difficult to process ideas even at the simplest level.

Without clear structures we struggle just to recall much more than unrelated scraps of information. As a result students do less well in exams than they could have expected, all because they haven’t learnt the skills involved in organising and structuring their understanding.

They sit down to revision with a near hopeless task facing them – mounds of notes, without a structure in sight, beyond the loose list of points. This could be described as the parable of two mental filing systems. One student uses a large brown box, into which she throws all her scraps of paper without any systematic order. Then, when she’s confronted with a question in the exam, she plunges her hand deep into the box in the despairing hope that she might find something useful. Sadly, all that she’s likely to come up with is something that’s, at best, trivial or marginally relevant, but which she’s forced to make the most of, because it’s all she’s got.

On the other hand there is the student who files all of her ideas systematically into a mental filing cabinet, knowing that, when she’s presented with a question, she can retrieve from her mind a structure of interlinked relevant arguments backed by quotations and evidence, from which she can develop her ideas confidently. And most of us are quite capable of doing this with considerable skill, if only we know how to.

Linear notes, perhaps, the most familiar and widely used note-taking strategy, because it adapts well to most needs. As we’ve already seen, at university the exams we prepare ourselves for are designed to assess more than just our comprehension, so notes in the form of a series of short descriptive paragraphs, and even the list, are of little real value. Exams at this level are concerned with a wider range of abilities, including our abilities to discuss, criticise and synthesise arguments and ideas from a variety of sources, to draw connections and contrasts, to evaluate and so on. To do all this requires a much more sophisticated and adaptable strategy that responds well to each new demand. It should promote our abilities, not stunt them by trapping us within a straitjacket.

Linear notes are particularly good at analytical tasks, recording the structure of arguments and passages. As you develop the structure, with each step or indentation you indicate a further breakdown of the argument into subsections. These in turn can be broken down into further subsections. In this way you can represent even the most complex argument in a structure that’s quite easy to understand.

Equally important, with clearly defined keywords, highlighted in capital letters or in different colours, it’s easy to recall the clusters of ideas and information that these keywords trigger of. In most cases it looks something like the following:

A Heading

1. Sub-heading

(a)

(b)

(c)

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

e. g.

(d)

2. Sub-heading

(a)

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

97

(b)

(c)

B Heading

1. Sub-heading

(a)

(b)

(i)

(ii)

(c)

(i)

(ii)

e. g.

d)

2. Sub-heading

3. Sub-heading

(a)

(b)

(c)

Needless to say, if we are to make all these successfully, we will have to make sure we organise our work in the most effective way. In the final chapters of this stage we will look at how to reorganise our retrieval system to tap into our own ideas and to pick up material wherever and whenever it appears. We will also examine the way we organize our time and the problems that can arise if we fail to do it effectively. Indeed, if we ignore either of these, we make it difficult for ourselves to get the most out of our abilities and to process our ideas well. Even though most of us routinely ignore it, organisation is the one aspect of our pattern of study that can produce almost immediate improvements in our work.

Here are a number of things you can do to make sure your structure works:

Keywords – choose sharp, memorable words to key off the points in your structure. In the notes on the Rise of Nazism the three main points are not difficult to remember, particularly with keywords, like ‘Humiliation’, ‘Ruins’ and the alliteration of ‘Weakness of Weimar’. But you need other words to key off the subsections, although you don’t need them for every step and every subsection in the notes.