Полная версия

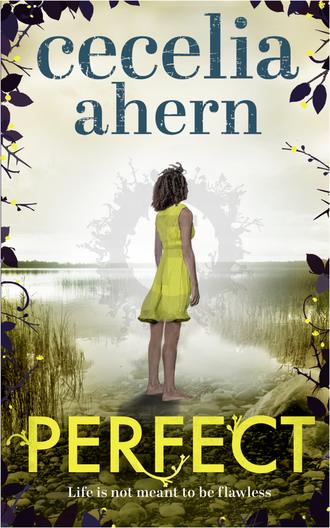

Perfect

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2017

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins website address is:

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © Cecelia Ahern 2017

All rights reserved.

Cover photographs © Shutterstock

Cecelia Ahern asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of the work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008125134

Ebook Edition © 2017 ISBN: 9780008125141

Version: 2017-02-20

For Yvonne Connolly, the perfect friend

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Part Two

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Part Three

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Chapter 80

Chapter 81

Chapter 82

Chapter 83

Chapter 84

Keep Reading …

Books by Cecelia Ahern

About the Publisher

PERFECT: ideal, model, faultless, flawless, consummate, quintessential, exemplary, best, ultimate; (of a person) having all the required or desirable elements, qualities or characteristics; as good as it is possible to be.

There’s the person you think you should be and there’s the person you really are. I’ve lost a sense of both.

A weed is just a flower growing in the wrong place.

They’re not my words, they’re my granddad’s.

He sees the beauty in everything, or perhaps it’s more that he thinks things that are unconventional and out of place are more beautiful than anything else. I see this trait in him every day: favouring the old farmhouse instead of the modernised gatehouse, brewing coffee in the ancient cast-iron pot over the open flames of the Aga instead of using the gleaming new espresso machine Mum bought him three birthdays ago that sits untouched, gathering dust, on the countertop. It’s not that he’s afraid of progress – in fact he is the first person to fight for change – but he likes authenticity, everything in its truest form. Including weeds: he admires their audacity, growing in places they haven’t been planted. It is this trait of his that has drawn me to him in my time of need and why he is putting his own safety on the line to harbour me.

Harbour.

That’s the word the Guild has used: Anybody who is aiding or harbouring Celestine North will face severe punishment. They don’t state the punishment, but the Guild’s reputation allows us to imagine. The danger of keeping me on his land doesn’t appear to scare Granddad; it makes him even more convinced of his duty to protect me.

“A weed is simply a plant that wants to grow where people want something else,” he adds now, stooping low to pluck the intruder from the soil with his thick, strong hands.

He has fighting hands, big and thick like shovels, but then in contradiction to that, they’re nurturing hands too. They’ve sown and grown, from his own land, and held and protected his own daughter and grandchildren. These hands that could choke a man are the same hands that reared a woman, that have cultivated the land. Maybe the strongest fighters are the nurturers because they’re connected to something deep in their core, they’ve got something to fight for, they’ve got something worth saving.

Granddad owns one hundred acres, not all strawberry fields like the one we’re in now, but he opens this part of the land up to the public in the summer months. Families pay to pick their own strawberries; he says the income helps him to keep things ticking over. He can’t stop it this year, not just for monetary reasons but because the Guild will know he’s hiding me. They’re watching him. He must keep going as he does every year, and I try not to think how it will feel to hear the sounds of children happily plucking and playing, or how much more dangerous it will be with strangers on the land who might unearth me in the process.

I used to love coming here as a child with my sister, Juniper, in the strawberry-picking season. At the end of a long day we would have more berries in our bellies than in our baskets, but it doesn’t feel like the same magical place any more. Now I’m de-weeding the soil where I once played make-believe.

I know that when Granddad talks about plants growing where they’re not wanted, he’s talking about me, like he’s invented his own unique brand of farmer therapy, but though he means well, it just succeeds in highlighting the facts to me.

I’m the weed.

Branded Flawed in five areas on my body and a secret sixth for good measure, for aiding a Flawed and lying to the Guild, I was given a clear message: society didn’t want me. They tore me from my terra firma, dangled me by my roots, shook me around, and tossed me aside.

“But who called these weeds?” Granddad continues, as we work our way through the beds. “Not nature. It’s people who did that. Nature allows them to grow. Nature gives them their place. It is people who brand them and toss them aside.”

“But this one is strangling the flowers,” I finally say, looking up from my work, back sore, nails filthy with soil.

Granddad fixes me with a look, tweed cap low over his bright blue eyes, always alert, always on the lookout, like a hawk. “They’re survivors, that’s why. They’re fighting for their place.”

I swallow my sadness and look away.

I’m a weed. I’m a survivor. I’m Flawed.

I’m eighteen years old today.

The person I think I should be: Celestine North, daughter of Summer and Cutter, sister of Juniper and Ewan, girlfriend of Art. I should have recently finished my final exams, be preparing for university, where I’d study mathematics.

Today is my eighteenth birthday.

Today I should be celebrating on Art’s father’s yacht with twenty of my closest friends and family, maybe even a fireworks display. Bosco Crevan promised to loan me the yacht for my big day as a personal gift. A gushing chocolate fountain on board for people to dip their marshmallows and strawberries. I imagine my friend Marlena with a chocolate moustache and a serious expression; I hear her boyfriend, as crass as usual, threatening to stick parts of himself in. Marlena rolling her eyes. Me laughing. A pretend fight, they always do that, enjoy the drama, just so they can make up.

Dad should be trying to be a show-off in front of my friends on the dance floor, with his body-popping and Michael Jackson impressions. I see my model mum standing out on deck in a loose floral summer dress, her long blonde hair blowing in the breeze like there’s a perfectly positioned wind machine. She’d be calm on the surface but all the time her mind racing, considering what is going on around her, what needs to be better, whose drink needs topping up, who appears left out of a conversation, and with a click of her fingers she’d float along in her dress and fix it.

My brother, Ewan, should be overdosing on marshmallows and chocolate, running around with his best friend, Mike, red-faced and sweating, finishing ends of beer bottles, needing to go home early with a stomach ache. I see my sister, Juniper, in the corner with a friend, her eye on it all, always in the corner, analysing everything with a content, quiet smile, always watching and understanding everything better than anyone else.

I see me. I should be dancing with Art. I should be happy. But it doesn’t feel right. I look up at him and he’s not the same. He’s thinner; he looks older, tired, unwashed and scruffy. He’s looking at me, eyes on me but his head is somewhere else. His touch is limp – a whisper of a touch – and his hands are clammy. It feels like the last time I saw him. It’s not how it’s supposed to be, not how it ever was, which was perfect, but I can’t even summon up those old feelings in my daydreams any more. That time of my life feels so far away from now. I left perfection behind a long time ago.

I open my eyes and I’m back in Granddad’s house. There’s a shop-bought cold apple tart in a foil tin sitting before me with a single candle in it. There’s the person I think I should be, though I can’t even dream about it properly without reality’s interruptions, and there’s the person I really am now.

This girl, on the run but frozen still, staring at the cold apple tart. Neither Granddad nor I are pretending things can continue like this. Granddad’s real; there’s no smoke and mirrors with him. He’s looking at me, sadly. He knows not to avoid the subject. Things are too serious for that now. We talk daily of a plan, and that plan changes daily. I have escaped my home; escaped my Whistleblower Mary May, a guard of the Guild, whose job it is to monitor my every move and assure that I’m complying with Flawed rules; and I’m now off the radar. I’m officially an ‘evader’. But the longer I stay here, the higher the chance I will eventually be found.

My mum told me to run away two weeks ago, an urgent whispered command in my ear that still gives me goose bumps when I recall it. The head of the Guild, Bosco Crevan, was sitting in our home, demanding my parents hand me over. Bosco is my ex-boyfriend’s dad, and we have been neighbours for a decade. Only a few weeks previously we’d been enjoying dinner together in our home. Now my mum would rather I disappear than be in his care again.

It can take a lifetime to build up a friendship – it can take a second to make an enemy.

There was only one important item that I needed with me when I ran: a note that had been given to my sister, Juniper, for me. The note was from Carrick. Carrick had been my holding-cell neighbour at Highland Castle, the home of the Guild. He watched my trial while he awaited his; he witnessed my brandings. All of my brandings, including the secret sixth on my spine. He is the only person who can possibly understand how I feel right now, because he’s going through the same thing.

My desire to find Carrick is immense, but it has been difficult. He managed to evade his Whistleblower as soon as he was released from the castle, and I’m guessing my profile didn’t make it easy for him to seek me out, either. Just before I ran away, he found me, rescued me from a riot in a supermarket. He brought me home – I was out cold at the time, our long-wished-for reunion not exactly what I’d imagined. He left me the note and vanished.

But I couldn’t get to him. Afraid of being recognised, I’d no way of finding my way around the city. So I called Granddad. I knew that his farm would be the Guild’s first port of call in finding me. I should be hiding somewhere else, somewhere safer, but on this land Granddad has the upper hand.

At least, that was the theory. I don’t think either of us thought that the Whistleblowers would be so relentless in their search for me. Since I arrived at the farm, there have been countless searches. So far they’ve failed to uncover my hiding place, but they come again and again, and I know my luck will eventually run out.

Each time, the Whistleblowers come so close to my hiding place I can barely breathe. I hear their footsteps, sometimes their breaths, as I’m crammed, jammed, into spaces, above and below, sometimes in places so obvious they don’t even look, sometimes so dangerous they wouldn’t dare to look.

I blink away my thoughts of them.

I look at the single flame flickering in the cold apple tart.

“Make a wish,” Granddad says.

I close my eyes and think hard. I have too many wishes and feel that none of them are within my reach. But I also believe that the moment we’re beyond making wishes is either the moment we’re truly happy, or the moment to give up.

Well, I’m not happy. But I’m not about to give up.

I don’t believe in magic, yet I see making wishes as a nod to hope, an acknowledgement of the power of will, the recognition of a goal. Maybe saying what you want to yourself makes it real, gives you a target to aim for, can help you make it happen. Channel your positive thoughts: think it, wish it, then make it happen.

I blow out the flame.

I’ve barely opened my eyes when we hear footsteps in the hallway.

Dahy, Granddad’s trusted farm manager, appears in the kitchen.

“Whistleblowers are here. Move.”

Granddad jumps up from the table so fast his chair falls backwards to the stone floor. Nobody picks it up. We’re not ready for this visit. Just yesterday the Whistleblowers searched the farm from top to bottom; we thought we’d be safe at least for today. Where is the siren that usually calls out in warning? The sound that freezes every soul in every home until the vehicles have passed by, leaving the lucky ones drenched with relief.

There is no discussion. The three of us hurry from the house. We instinctively know we have run out of luck with hiding me inside. We turn right, away from the drive lined with cherry blossom trees. I don’t know where we’re going, but it’s away, as far from the entrance as possible.

Dahy talks as we run. “Arlene saw them from the tower. She called me. No sirens. Element of surprise.”

There’s a ruined Norman tower on the land, which serves Granddad well as a lookout tower for Whistleblowers. Ever since I’ve arrived he’s had somebody on duty day and night, each of the farmworkers taking shifts.

“And they’re definitely coming here?” Granddad asks, looking around fast, thinking hard. Plotting, planning. And I regret to admit I detect panic in his movements. I’ve never seen it in Granddad before.

Dahy nods.

I increase my pace to keep up with them. “Where are we going?”

They’re silent. Granddad is still looking around as he strides through his land. Dahy watches Granddad, trying to read him. Their expressions make me panic. I feel it in the pit of my stomach, the alarming rate of my heartbeat. We’re moving at top speed to the farthest point of Granddad’s land, not because he has a plan but because he doesn’t. He needs time to think of one.

We rush through the fields, through the strawberry beds that we were working in only hours ago.

We hear the Whistleblowers approach. For previous searches there has been only one vehicle, but now I think I hear more. Louder engines than usual, perhaps vans instead of cars. There are usually two Whistleblowers to a car, four to a van. Do I hear three vans? Twelve possible Whistleblowers.

I start to tremble: this is a full-scale search. They’ve found me; I’m caught. I breathe in the fresh air, feeling my freedom slipping away from me. I don’t know what they will do to me, but under their care last month I received painful brands on my skin, the red letter F seared on six parts of my body. I don’t want to stick around to discover what else they’re capable of.

Dahy looks at Granddad. “The barn.”

“They’re on to that.”

They look far out to the land as if the soil will provide an answer. The soil.

“The pit,” I say suddenly.

Dahy looks uncertain. “I don’t think that’s a—”

“It’ll do,” Granddad says with an air of finality and charges off in the direction of the pit.

It was my idea, but the thought of it makes me want to cry. I feel dizzy at the prospect of hiding there. Dahy holds out his arm to allow me to walk ahead of him, and I see sympathy and sadness in his eyes.

I also see ‘Goodbye.’

We follow Granddad to the clearing near the black forest that meets his land. He and Dahy spent this morning digging a hole in the ground, while I lay on the soil beside them, lazily twirling a dandelion clock between my fingers and watching it slowly dismantle in the breeze.

“You’re like gravediggers,” I’d said sarcastically.

Little did I know how true my words would become.

The cooking pit, according to Granddad, is the simplest and most ancient cooking structure. Also called an earth oven, it’s a hole in the ground used to trap heat to bake, smoke, or steam food.

To bake the food, the fire is allowed to burn to a smoulder. The food is placed in the pit and covered. The earth is filled back over everything – potatoes, pumpkins, meat, anything you want – and the food is left for a full day to cook. Granddad carries out this tradition every year with the workers on his farm, but usually at harvest time, not in May. He’d decided to do it now for “team building”, he called it, at a time when we all needed reinforcement, to come together. All of Granddad’s farmworkers are Flawed, and after facing the relentless searches from Whistleblowers and with each of his workers under the eye of the Guild more than ever, he felt everybody needed a morale boost.

I never knew Granddad employed Flawed, not until I got here two weeks ago. I don’t remember seeing his farmworkers when we visited the farm and Mum and Dad never mentioned them. Perhaps they’d been asked to stay out of our view; perhaps they were always there and, like most Flawed to me before I became one, seemed invisible.

I understand now that this helped drive a wedge between Granddad and Mum, her disapproving of his criticism of the Guild, the government-supported tribunal that puts people on trial for their unethical, immoral acts. We thought his rants were nothing but conspiracy theories, bitter about how his taxpayer’s money was being spent. Turns out he was right. I also see now that Granddad was like Mum’s dirty little secret. As a high-profile model, she represented perfection, on the outside at least, and while she was hugely successful around the world, she couldn’t let her reputation in Humming be damaged. Having such an outspoken father who was on the Flawed side was a threat to her image. I understand that now.

There are some employers who treat Flawed like slaves. Long hours and on the minimum wage, if they’re lucky. Many Flawed are just happy to be employed and work for accommodation and food. The majority of Flawed are educated, upstanding citizens. They aren’t criminals; they haven’t carried out any illegal acts. They made moral or ethical decisions that were frowned upon by society and they were branded for it. An organised public shaming, I suppose. The judges of the Guild like to call themselves the “Purveyors of Perfection”.

Dahy was a teacher. He was caught on security cameras in school grabbing a child roughly.

I’ve also learned that reporting people as Flawed to the Guild is a weapon that people use against each other. They wipe out the competition, leaving a space for themselves to step into, or they use it as a form of revenge. People abuse the system. The Guild is one gaping loophole for opportunists and hunters.

I broke a fundamental rule: do not aid the Flawed. This act actually carries a prison sentence, but I was found Flawed instead. Before my trial, Crevan was trying to find a way to help me. The plan was that I was supposed to lie and say that I didn’t help the old man. But I couldn’t lie; I admitted the truth. I told them all that the Flawed man was a human being who needed and deserved to be helped. I humiliated Crevan, made a mockery of his court, or that’s how he saw it anyway.